From line to landscape: Tanaka Ryōhei and the quiet radicalism of etching

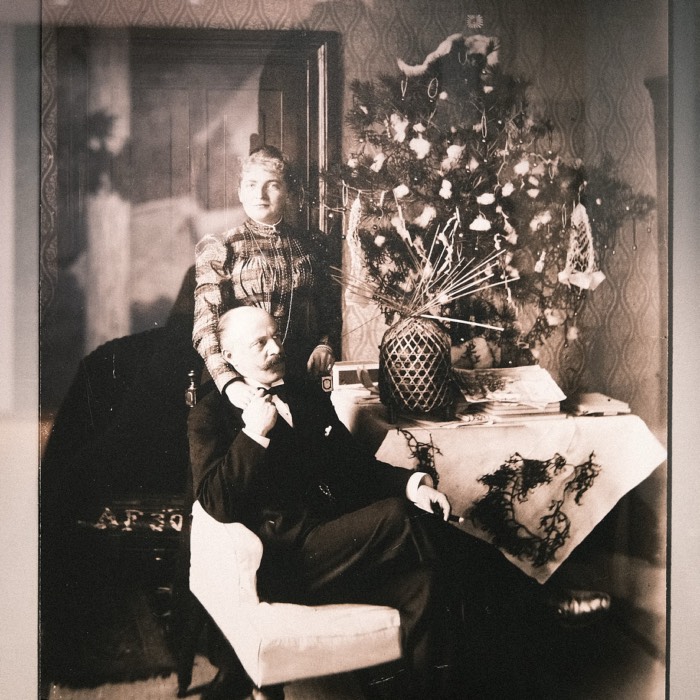

In December 2024, parallel to the exhibition Expeditions – travelogues and photographs by the museum founders 1897-1899, I also visited the exhibition From Line to Landscape at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln. The show focused on the work of Tanaka Ryōhei and offered a rare opportunity to see a comprehensive selection of his works spanning more than five decades.

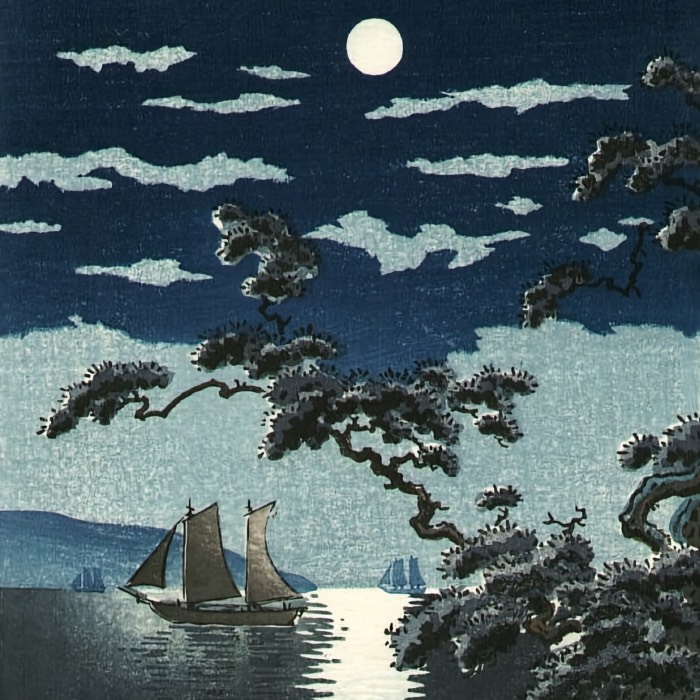

Tanaka Ryōhei, ‘From Line to Landscape’, Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024.

Tanaka Ryōhei, ‘From Line to Landscape’, Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024.

Tanaka is well known for his meticulous etchings of rural Japan, particularly snow-covered landscapes and traditional architecture. The exhibition presented over 100 works, including early experiments, mature pieces, and late works, allowing viewers to trace the evolution of his technique and thematic focus.

Tanaka Ryōhei, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024.

Tanaka Ryōhei, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024.

Tanaka Ryōhei: A brief biographical note

Tanaka Ryōhei (1933–2019) was a Japanese printmaker who lived and worked in Takatsuki, near Kyoto. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Tanaka began his artistic career relatively late. In 1963, he studied etching under Furuno Yoshio, and one year later he joined the Kyoto Etchers’ Group, marking his formal entry into printmaking.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Abandoned House of Tokashima, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint 1993. Ryōher’s youth was partly spent in the countryside of his grandfather of which the scenery remained embedded in him throughout his life. His repeated depictions of abandoned farmhouses may stem from a certain sadness of seeing these sustainable organic structures disappear during his own lifetime. This etching of an abandoned and dilapidated farmhouse is particularly poignant as it gives the impression that a swarm of insects has infested the remains of the thatched roof.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Abandoned House of Tokashima, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint 1993. Ryōher’s youth was partly spent in the countryside of his grandfather of which the scenery remained embedded in him throughout his life. His repeated depictions of abandoned farmhouses may stem from a certain sadness of seeing these sustainable organic structures disappear during his own lifetime. This etching of an abandoned and dilapidated farmhouse is particularly poignant as it gives the impression that a swarm of insects has infested the remains of the thatched roof.

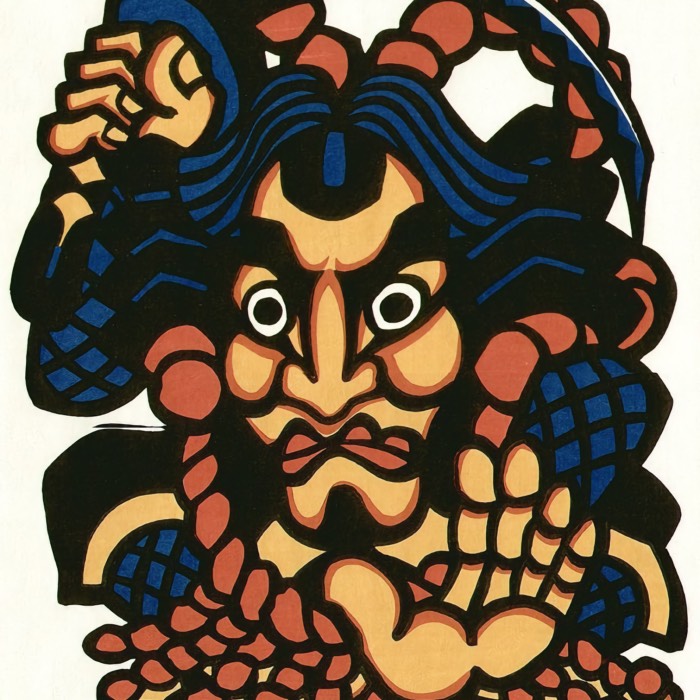

Onigawara. These traditional Japanese onigawara (roof tiles with demon faces) were a significant source of inspiration for Tanaka Ryōhei. In Japanese culture, onigawara serve to protect buildings by warding off evil spirits and keeping misfortune at bay. The expressive forms and protective symbolism of these tiles fascinated Tanaka, who incorporates elements of this heritage into his art.

Onigawara. These traditional Japanese onigawara (roof tiles with demon faces) were a significant source of inspiration for Tanaka Ryōhei. In Japanese culture, onigawara serve to protect buildings by warding off evil spirits and keeping misfortune at bay. The expressive forms and protective symbolism of these tiles fascinated Tanaka, who incorporates elements of this heritage into his art.

Tanaka devoted himself almost exclusively to etching and related intaglio techniques. Over the course of his career, he produced more than 770 etchings, typically printed in small editions ranging from 50 to 150 impressions. After completion, he deliberately destroyed the copper plates to prevent further prints from being made.

The vast majority of his works are monochrome, with occasional use of aquatint or restrained color accents. Tanaka continued working well into old age; his final print was completed in 2013.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Autumn Temple, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 2008. Apart from the black key-plate, the artist used a second plate for the colours which he had to wipe in the a la poupee technique. This technique entails inking the same plate with various coloured inks before wiping the excess ink off. In this way one can add two or more colours to the image by using just the one colour plate. Tanaka was well used to this method and cleverly separated the three colour sections bitten on the second plate with enough space in between to make the wiping less difficult. In between the foliage of the maple tree he carefully etched the rooftiles in small sections to make them visible and create space between tree and roof. The printing of an edition of 100 plus 10 artists proofs would have been a very time consuming task. Having now reached the age of seventy five, he would have been able to perhaps print only ten of this etchings in one day.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Autumn Temple, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 2008. Apart from the black key-plate, the artist used a second plate for the colours which he had to wipe in the a la poupee technique. This technique entails inking the same plate with various coloured inks before wiping the excess ink off. In this way one can add two or more colours to the image by using just the one colour plate. Tanaka was well used to this method and cleverly separated the three colour sections bitten on the second plate with enough space in between to make the wiping less difficult. In between the foliage of the maple tree he carefully etched the rooftiles in small sections to make them visible and create space between tree and roof. The printing of an edition of 100 plus 10 artists proofs would have been a very time consuming task. Having now reached the age of seventy five, he would have been able to perhaps print only ten of this etchings in one day.

Etching in Japan: A late and uneasy medium

Etching has a long history in Europe but a comparatively fragile one in Japan. Early experiments by Shiba Kōkan in the late 18th century remained isolated. During the Edo period, copperplate techniques were associated with rangaku, “Dutch learning”, and later fell under political suspicion. When Western printmaking techniques re-entered Japan in the Meiji period, they were largely adopted for technical reproduction rather than artistic exploration.

Even in the early 20th century, etching remained marginal. Woodblock printmaking dominated both tradition and reform, from shin hanga to sōsaku hanga. Etching only began to gain broader recognition after World War II, particularly through international exhibitions and institutions such as the College Women’s Association of Japan print shows.

What I learned from the exhibition, is, that against this background, Tanaka Ryōhei’s career appears not as a continuation of an established lineage as it is the case for many Japanese printmakers, but as a deliberate and sustained commitment to a medium that had no secure place in Japanese art.

Tanaka Ryōhei’s method: Line as structure, not contour

Tanaka worked almost exclusively with intaglio techniques, primarily line etching and aquatint, supplemented by drypoint, roulette, sugar-lift, scraping, and burnishing. Intaglio printmaking involves incising an image into a metal plate, inking the recessed lines, wiping the surface clean, and pressing damp paper onto the plate under high pressure to transfer the inked image.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Tools for etching, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024

Tanaka Ryōhei, Tools for etching, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024

The exhibition emphasized how controlled and cumulative his process was. He worked on a single plate at a time, drawing directly into the ground, biting repeatedly, stopping out hundreds of lines, and relying on experience rather than mechanical timing.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Preliminary sketches and preliminary studies, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024

Tanaka Ryōhei, Preliminary sketches and preliminary studies, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024

What distinguishes his work is not virtuosity for its own sake, but the structural use of line. Lines do not describe surfaces; they build them. Roofs, walls, trees, and snowfields emerge from dense cross-hatching, shallow bites, and carefully calibrated plate tone. Large areas of the plate are often left untouched, allowing the white of the paper to function as snow, mist, or light. In many works, more than half the image is unetched.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Barn and House No. 3, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1993. Tanaka created this impressive work shortly before he underwent long-postponed heart surgery. During his convalescence he produced a number of smaller etchings. The edition of the present work was printed in the following year after the artist had fully recovered. The richly varied thatch, particularly in the roof of the smaller building, is achieved by an extreme density of deeply etched lines. When using such a technique the artist has to take great care that the individual lines do not get bitten too deeply. This could affect the tiny copper ridges that define each line and hold the ink. A sideways breakthrough of these minute ridges would create a flat section which will no longer hold the ink and print as blank instead of the desired hues of black.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Barn and House No. 3, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1993. Tanaka created this impressive work shortly before he underwent long-postponed heart surgery. During his convalescence he produced a number of smaller etchings. The edition of the present work was printed in the following year after the artist had fully recovered. The richly varied thatch, particularly in the roof of the smaller building, is achieved by an extreme density of deeply etched lines. When using such a technique the artist has to take great care that the individual lines do not get bitten too deeply. This could affect the tiny copper ridges that define each line and hold the ink. A sideways breakthrough of these minute ridges would create a flat section which will no longer hold the ink and print as blank instead of the desired hues of black.

Color appears sparingly and late. Even then, it rarely functions decoratively. Color plates are used to deepen atmosphere, weight, or temperature, while the core image remains anchored in monochrome structure. Several works appear polychrome at first glance, yet are printed from a single plate through subtle control of ink density and biting depth.

Tanaka Ryōhei, The Main Hall of Tō-ji, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1999. The main hall of the Tō-ji temple is one of many UNESCO world heritage monuments in Kyoto. The present main hall was rebuilt in the late 15th century, after the original building, dating from the late 800s, was destroyed by fire. Tanaka shows the building as if seen through a telephoto lens. The dramatically shortened view is emphasized by the repoussoir of the trees on either side and the big stone lantern in the foreground. The etching was done on two plates: the black key plate and a plate with three sections of aquatinted areas that were inked a la poupee with ochre, green and light-red.

Tanaka Ryōhei, The Main Hall of Tō-ji, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1999. The main hall of the Tō-ji temple is one of many UNESCO world heritage monuments in Kyoto. The present main hall was rebuilt in the late 15th century, after the original building, dating from the late 800s, was destroyed by fire. Tanaka shows the building as if seen through a telephoto lens. The dramatically shortened view is emphasized by the repoussoir of the trees on either side and the big stone lantern in the foreground. The etching was done on two plates: the black key plate and a plate with three sections of aquatinted areas that were inked a la poupee with ochre, green and light-red.

Landscape without horizon

Across the decades, Tanaka repeatedly returned to elevated or compressed viewpoints. Roofs are seen from above, walls from oblique angles, trees from below. Perspective is often flattened or deliberately distorted. Vertical lines frequently refuse to converge, producing images that oscillate between realism and abstraction.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Roofs Along Kurama Road, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1994. This cropped and shortened view of the roofs with the repoussoir of a tree trunk is similar to Mountain Village of 1992. A new element in this work is the slightly parabolic view and the contrast between the sharply etched grasses and leaves in the foreground and the soft density of the pine forest on the opposite slope.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Roofs Along Kurama Road, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1994. This cropped and shortened view of the roofs with the repoussoir of a tree trunk is similar to Mountain Village of 1992. A new element in this work is the slightly parabolic view and the contrast between the sharply etched grasses and leaves in the foreground and the soft density of the pine forest on the opposite slope.

This approach aligns Tanaka less with Western landscape traditions than with Japanese painting practices, particularly nihonga and ink painting, where space is constructed through rhythm, cropping, and implication rather than optical coherence. Several works explicitly echo scroll painting, both in their vertical formats and in their telephoto-like compression of space.

At the same time, Tanaka’s images are unmistakably modern. The repeated focus on disappearing rural architecture, abandoned farmhouses, and altered landscapes registers social change without illustration or commentary. Snow becomes not only a motif, but a structural device: A way of erasing, isolating, and quieting the image.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Snow and Thatched Roof, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1993. Even a well-trained eye could easily mistake this print for a multi plate (of a multi plate color etching), which it technically is not. The lineetched roof and the aquatinted sky were etched into - and printed off - the same plate. The drawn lines were etched much deeper than the aquatinted areas. Tanaka carefully mixed black and indigo ink so that the deeply etched lines still show as almost black: the blueish hue, on the other hand, is the result of the thin layer of ink remaining in the rather shallowly bitten aquatint section of the sky. This gives the impression that two plates, one black and one indigo, were used. The result is a rare technical feat, one that Tanaka was able to repeat only once more in his Snow Bird of 2008.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Snow and Thatched Roof, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1993. Even a well-trained eye could easily mistake this print for a multi plate (of a multi plate color etching), which it technically is not. The lineetched roof and the aquatinted sky were etched into - and printed off - the same plate. The drawn lines were etched much deeper than the aquatinted areas. Tanaka carefully mixed black and indigo ink so that the deeply etched lines still show as almost black: the blueish hue, on the other hand, is the result of the thin layer of ink remaining in the rather shallowly bitten aquatint section of the sky. This gives the impression that two plates, one black and one indigo, were used. The result is a rare technical feat, one that Tanaka was able to repeat only once more in his Snow Bird of 2008.

Consistency as artistic position

One of the most striking aspects of Tanaka Ryōhei’s work is its consistency. Over more than fifty years, he refined a narrow set of subjects, formats, and techniques rather than expanding them. Certain plate sizes recur hundreds of times. Certain motifs reappear with incremental variation. This restraint is not limitation, but method.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Barn and House No. 1, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint 1989. This etching on a larger scale would become the first of a number of works with the same title. Whereas the later works of a similar subject with the same title all show a thatched main house and a equally thatched smaller structure, Tanaka purposefully and carefully creates the contrast of his famous old fashioned farmhouses juxtaposed to a small modern motor venicle such as the Suzuki and Honda small trucks often used by the local farmers to this day.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Barn and House No. 1, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint 1989. This etching on a larger scale would become the first of a number of works with the same title. Whereas the later works of a similar subject with the same title all show a thatched main house and a equally thatched smaller structure, Tanaka purposefully and carefully creates the contrast of his famous old fashioned farmhouses juxtaposed to a small modern motor venicle such as the Suzuki and Honda small trucks often used by the local farmers to this day.

Seen as a whole, the work demonstrates how an artist can build extraordinary expressive range from a deliberately restricted vocabulary. The exhibition made clear that Tanaka’s achievement lies not in stylistic innovation, but in the cumulative precision of his practice.

Impressions from the exhibition

Here are some further photos I took at the exhibition in order to give you a better impression of Tanaka Ryōhei’s work. The caption texts are taken from the accompanying booklet to the exhibition.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Pagoda, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1966. This pagoda is located in the grounds of Toji temple in Kyoto. The slightly off-center view adds a certain lightness to the elegance of the tower. Note the thinly etched lines of the flying eaves tiles of the three upper stories, which give the illusion of distance as well as the impression of looking up to an overcast sky.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Pagoda, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1966. This pagoda is located in the grounds of Toji temple in Kyoto. The slightly off-center view adds a certain lightness to the elegance of the tower. Note the thinly etched lines of the flying eaves tiles of the three upper stories, which give the illusion of distance as well as the impression of looking up to an overcast sky.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Winter Orchard No. 1, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024.Color etching, etching, aquatinta and sugar-lift aquatint, 1967. This is the third etching in the relatively small oeuvre of Tanaka’s multi-plate color prints, and an experimental one. The composition has a some-what abstract foreground, and a hillside orchard divided by a flight of steps leading to a shed on the hilltop. The bare branches of the fruit trees are graphic and detailed, yet the entire composition is abstract. This elevated view of an orchard on a hillside reminds us of a work from 1960, by nihonga painter Iwahashi Fien (1903-1999) In early-1960s Japan, a more subtle graphically abstract realism was gaining ground after the waves of raw and experimental Western-style abstraction.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Winter Orchard No. 1, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024.Color etching, etching, aquatinta and sugar-lift aquatint, 1967. This is the third etching in the relatively small oeuvre of Tanaka’s multi-plate color prints, and an experimental one. The composition has a some-what abstract foreground, and a hillside orchard divided by a flight of steps leading to a shed on the hilltop. The bare branches of the fruit trees are graphic and detailed, yet the entire composition is abstract. This elevated view of an orchard on a hillside reminds us of a work from 1960, by nihonga painter Iwahashi Fien (1903-1999) In early-1960s Japan, a more subtle graphically abstract realism was gaining ground after the waves of raw and experimental Western-style abstraction.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Wooden Lattice No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1972. A row of townhouses and warehouses as seen from the opposite side of the street through a kōshi, the traditional wooden lattice screen which is indispensable to Japanese architecture. The sense of distance between the kōshi, which is partly blocking our view, and the houses opposite is achieved by the strongly converging lines of the tiled roofs. The location is probably a street in Kyoto’s Nishijin district, which is famous for its traditional machiya (townhouses). The contrast between the dark bold structure in the foreground and the buildings, rendered in a lighter manner, beyond, gives the impression of looking out from the inside. Like many other Japanese traditional architectural features, kōshi have often been used as pictorial ploys.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Wooden Lattice No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1972. A row of townhouses and warehouses as seen from the opposite side of the street through a kōshi, the traditional wooden lattice screen which is indispensable to Japanese architecture. The sense of distance between the kōshi, which is partly blocking our view, and the houses opposite is achieved by the strongly converging lines of the tiled roofs. The location is probably a street in Kyoto’s Nishijin district, which is famous for its traditional machiya (townhouses). The contrast between the dark bold structure in the foreground and the buildings, rendered in a lighter manner, beyond, gives the impression of looking out from the inside. Like many other Japanese traditional architectural features, kōshi have often been used as pictorial ploys.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Jingo-ji, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching und roulette, 1972. After the success of his unconventional Tree top branches at Sanzenin Tanaka continued to explore new angles based on photographic viewpoints. He usually made the first sketches on the spot, looking for new challenges for the composition, but instantly determining the angle of view. Jingo-ji forces the viewer to focus on the stone steps leading up to the temple gate. The image is executed in pure hardground line etching with roulette nuances for the stone.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Jingo-ji, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching und roulette, 1972. After the success of his unconventional Tree top branches at Sanzenin Tanaka continued to explore new angles based on photographic viewpoints. He usually made the first sketches on the spot, looking for new challenges for the composition, but instantly determining the angle of view. Jingo-ji forces the viewer to focus on the stone steps leading up to the temple gate. The image is executed in pure hardground line etching with roulette nuances for the stone.

Enlarged version of “Gansen-ji” at one of the exhibition walls.

Enlarged version of “Gansen-ji” at one of the exhibition walls.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Gansen-ji, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1980. Tanaka chose the subject of the three-storied pagoda of Gansen-ji, with its elegantly shaped roofs and lush surroundings after eight years of predominantly depicting secular rural architecture. It was fourteen years since Pagoda of 1966. The Gansen-ji pagoda was built in 1442 on the eastern slopes of the town of Kizugawa in Kyoto prefecture. Its structure is so slender that the three roofs seem to float among the trees without any support from a tower.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Gansen-ji, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1980. Tanaka chose the subject of the three-storied pagoda of Gansen-ji, with its elegantly shaped roofs and lush surroundings after eight years of predominantly depicting secular rural architecture. It was fourteen years since Pagoda of 1966. The Gansen-ji pagoda was built in 1442 on the eastern slopes of the town of Kizugawa in Kyoto prefecture. Its structure is so slender that the three roofs seem to float among the trees without any support from a tower.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Big White Tree, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1982. This work seems to be a ‘negative’ version of an etching with exactly the same dimensions Tanaka made eleven years earlier entitled Spring is Near. The fanning out of what appears to be brightly lit branches behind the roof as opposed to the more or less vertical lines of the branches in the earlier print show the artist’s constant search for innovation and artistic expression. This work needs to be scrutinized from up close. It is mesmerizing how Tanaka managed to block out the ever thinner growing lines of the branches with the syrupy block-out varnish, thereby protecting them from the aggressive deep biting of the mordant, which deep biting would create the solid black night sky. The thinnest branches are not even a fraction of a millimetre wide yet the nitric acid did not bite ‘underneath’ these very fine lines. A masterly feat of the use of stop-out varnish.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Big White Tree, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1982. This work seems to be a ‘negative’ version of an etching with exactly the same dimensions Tanaka made eleven years earlier entitled Spring is Near. The fanning out of what appears to be brightly lit branches behind the roof as opposed to the more or less vertical lines of the branches in the earlier print show the artist’s constant search for innovation and artistic expression. This work needs to be scrutinized from up close. It is mesmerizing how Tanaka managed to block out the ever thinner growing lines of the branches with the syrupy block-out varnish, thereby protecting them from the aggressive deep biting of the mordant, which deep biting would create the solid black night sky. The thinnest branches are not even a fraction of a millimetre wide yet the nitric acid did not bite ‘underneath’ these very fine lines. A masterly feat of the use of stop-out varnish.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Birds in Flight, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1982. Turning away from the immobility of his favorite subjects, Tanaka at times sought to create a sense of movement in his etchings. Sometimes he achieved this by suggesting wind and the elements, either with etched lines or with aquatint, sometimes with the suggestion of falling snow. In a number of works from 1982, he added flying birds. Birds in Flight is an excellent example of this group. The birds beyond the roof and the trees provide a sense of space and movement.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Birds in Flight, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1982. Turning away from the immobility of his favorite subjects, Tanaka at times sought to create a sense of movement in his etchings. Sometimes he achieved this by suggesting wind and the elements, either with etched lines or with aquatint, sometimes with the suggestion of falling snow. In a number of works from 1982, he added flying birds. Birds in Flight is an excellent example of this group. The birds beyond the roof and the trees provide a sense of space and movement.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Big Tree No. 1 (detail), from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1981. In early works Tanaka drew the images as if seen through a telephoto lens, but did not apply convergence. He later developed a similar telephotographic viewpoint, this time even emphasizing convergence. Sometimes this almost resulted in a wide-angle view, as in this etching. The big tree looming behind the roof not only seems to overwhelm the farmhouse, but also the viewer. The entire surface of this work has been etched with the needle. Only the dark branches and the shadow of the gable were given an added aquatint treatment.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Big Tree No. 1 (detail), from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1981. In early works Tanaka drew the images as if seen through a telephoto lens, but did not apply convergence. He later developed a similar telephotographic viewpoint, this time even emphasizing convergence. Sometimes this almost resulted in a wide-angle view, as in this etching. The big tree looming behind the roof not only seems to overwhelm the farmhouse, but also the viewer. The entire surface of this work has been etched with the needle. Only the dark branches and the shadow of the gable were given an added aquatint treatment.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Snow and Thatched Roof No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1982. This seemingly simple composition the artist could have conceived to be made on a larger scale as one of his more monumental etchings, yet he chose to keep the work intimate. As in the following year this small etching would surprisingly be Tanaka’s only snow-themed work of 1982. In the background, particularly on the top left, he depicts a faint tree-studded mountain covered in snow of which further up shows whiter because of the heavier snow higher up. On the top right a mountain slope is seen, similarly whiter, between the branches of the bare tree. These details are very subtle and easily missed. Perhaps all Tanaka’s intimate etchings should be admired from up close and were never intended to be hung as art on the wall.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Snow and Thatched Roof No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1982. This seemingly simple composition the artist could have conceived to be made on a larger scale as one of his more monumental etchings, yet he chose to keep the work intimate. As in the following year this small etching would surprisingly be Tanaka’s only snow-themed work of 1982. In the background, particularly on the top left, he depicts a faint tree-studded mountain covered in snow of which further up shows whiter because of the heavier snow higher up. On the top right a mountain slope is seen, similarly whiter, between the branches of the bare tree. These details are very subtle and easily missed. Perhaps all Tanaka’s intimate etchings should be admired from up close and were never intended to be hung as art on the wall.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Big Roof, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1980. In this design the shōji doors and the veranda F on the ground floor are dwarfed by the roof. The moon is mysteriously hiding in the mist Big Roof was printed in sepia ink, adding a warm tone to the organic textures of the farmhouse.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Big Roof, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1980. In this design the shōji doors and the veranda F on the ground floor are dwarfed by the roof. The moon is mysteriously hiding in the mist Big Roof was printed in sepia ink, adding a warm tone to the organic textures of the farmhouse.

Tanaka Ryōhei, House with a Shoji Door No. 1, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1980. This etching was made immediately after Snow Is Coming No. 2. The complexity of its composition of various wall textures contrasts sharply with the quietude of the previous work. To juxtapose various structures in combination with foreshortening takes courage and a great deal of mastery. Yet, Tanaka has managed to avoid a jumble of textures, and the spatial correlation of the four walls is completely clear. The angle of the roofline of the white kura (storehouse) wall on the right echoes the shape of the white paper in the shōji door.

Tanaka Ryōhei, House with a Shoji Door No. 1, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1980. This etching was made immediately after Snow Is Coming No. 2. The complexity of its composition of various wall textures contrasts sharply with the quietude of the previous work. To juxtapose various structures in combination with foreshortening takes courage and a great deal of mastery. Yet, Tanaka has managed to avoid a jumble of textures, and the spatial correlation of the four walls is completely clear. The angle of the roofline of the white kura (storehouse) wall on the right echoes the shape of the white paper in the shōji door.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Mount Ibuki, Early Spring, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1980. A generous panoramic view of Mount Ibuki. The dramatically dark sky accentuates the whiteness of the lingering snow. A flock of wild ducks or geese fly westward at a high altitude, probably returning to nearby Lake Biwa. Traversing the mountain flank, a road climbs to the limestone quarry that has scarred the southeastern side. Except for the sky, which is aquatinted, the plate is line etched, from the darkest trees to the finest gradations of grays in the snow. A rare image in the artist’s oeuvre.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Mount Ibuki, Early Spring, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1980. A generous panoramic view of Mount Ibuki. The dramatically dark sky accentuates the whiteness of the lingering snow. A flock of wild ducks or geese fly westward at a high altitude, probably returning to nearby Lake Biwa. Traversing the mountain flank, a road climbs to the limestone quarry that has scarred the southeastern side. Except for the sky, which is aquatinted, the plate is line etched, from the darkest trees to the finest gradations of grays in the snow. A rare image in the artist’s oeuvre.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Yamato Alley, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1979. By the late 1970s Tanaka’s etchings had become so popular, especially overseas, that he and Yamada Tetsuo decided to increase the number of prints in the artist’s editions from 100 to 120, and even 150, depending on image and size. Yamato Alley is a finely etched and aquatinted work. The bleak winter light falls on the steep- gabled roofs of the farmhouses which were once typical for this semirural area southwest of Kyoto. The artist used a very fine resin dust to aquatint the areas of the distant mountain and the walls, and much coarser granules of resin in a second aquatint to produce the effect of pebbles and sand on the path in the foreground.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Yamato Alley, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1979. By the late 1970s Tanaka’s etchings had become so popular, especially overseas, that he and Yamada Tetsuo decided to increase the number of prints in the artist’s editions from 100 to 120, and even 150, depending on image and size. Yamato Alley is a finely etched and aquatinted work. The bleak winter light falls on the steep- gabled roofs of the farmhouses which were once typical for this semirural area southwest of Kyoto. The artist used a very fine resin dust to aquatint the areas of the distant mountain and the walls, and much coarser granules of resin in a second aquatint to produce the effect of pebbles and sand on the path in the foreground.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Autumn Scene, Ōhara No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1977. The pale autumn mist partly hides the mountains in the distance. A few fruits have been left on the persimmon tree in a gesture of kimamori, an old custom which is supposed to ensure a good harvest in the coming year. In the 1970s, the village of Ohara, just northeast of Kyoto, still boasted a number of thatched farmhouses. Today there are none left, except for one or two where the thatch has been covered with a protective corrugated iron cladding.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Autumn Scene, Ōhara No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1977. The pale autumn mist partly hides the mountains in the distance. A few fruits have been left on the persimmon tree in a gesture of kimamori, an old custom which is supposed to ensure a good harvest in the coming year. In the 1970s, the village of Ohara, just northeast of Kyoto, still boasted a number of thatched farmhouses. Today there are none left, except for one or two where the thatch has been covered with a protective corrugated iron cladding.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Snowy Hatago, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1977. The tiny hamlet of Hatago is situated in the mountains north of Kyoto about halfway between the city and the Sea of Japan. It lies in a narrow valley and up until the 1970-s its remoteness had helped to preserve the buildings in that little agricultural community. In 1977 most of the farmhouses, huddled together, still had their thatched roofs intact and were well maintained. Nowadays, half a century later, the roofs of the farmhouses that did survive have had a modern tiling placed on them to protect the thatch and the wooden support structure which supports it, from the inhospitable wintery conditions of inland Honshu. This is the first somewhat ‘panoramic’ landscape that Tanaka produced. The faintly visible curved lines in the snowed-under the terraced paddies in the foreground seem to invite us to follow the snow down to the right, to the lower valley beyond.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Snowy Hatago, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1977. The tiny hamlet of Hatago is situated in the mountains north of Kyoto about halfway between the city and the Sea of Japan. It lies in a narrow valley and up until the 1970-s its remoteness had helped to preserve the buildings in that little agricultural community. In 1977 most of the farmhouses, huddled together, still had their thatched roofs intact and were well maintained. Nowadays, half a century later, the roofs of the farmhouses that did survive have had a modern tiling placed on them to protect the thatch and the wooden support structure which supports it, from the inhospitable wintery conditions of inland Honshu. This is the first somewhat ‘panoramic’ landscape that Tanaka produced. The faintly visible curved lines in the snowed-under the terraced paddies in the foreground seem to invite us to follow the snow down to the right, to the lower valley beyond.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Deserted House with Lingering Snow, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1977. Most of Tanaka’s landscapes lack human figures, and in this work too the inhabitants seem to have passed on or moved away. The amado (storm door) is closed and in bad repair. The gable has started to collapse. The snow ies heavily on the thatched roof. Only a few abandoned tools, buckets and barrels testify to one-time human occupancy.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Deserted House with Lingering Snow, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1977. Most of Tanaka’s landscapes lack human figures, and in this work too the inhabitants seem to have passed on or moved away. The amado (storm door) is closed and in bad repair. The gable has started to collapse. The snow ies heavily on the thatched roof. Only a few abandoned tools, buckets and barrels testify to one-time human occupancy.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Hatago in Autumn, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1977. Up until this point in his oeuvre the artist had produced quite a number of pure line etchings, also of larger sizes, however none of them show the exhaustive variety of textures and etching techniques which he employed in this work. Tanaka took his inspiration for the theme from the small farming community of Hatago, yet the entire view is composed and concertinaed to form a mosaic-like image in strong telephotolike foreshortening behind the ripe persimmons on the branch in the foreground. It is technically intensely demanding to produce such a range of different textures each with the etching needle and in hues ranging from black to white. Although we may suspect light aquatinting in some areas, no aquatint has been used in this etching.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Hatago in Autumn, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1977. Up until this point in his oeuvre the artist had produced quite a number of pure line etchings, also of larger sizes, however none of them show the exhaustive variety of textures and etching techniques which he employed in this work. Tanaka took his inspiration for the theme from the small farming community of Hatago, yet the entire view is composed and concertinaed to form a mosaic-like image in strong telephotolike foreshortening behind the ripe persimmons on the branch in the foreground. It is technically intensely demanding to produce such a range of different textures each with the etching needle and in hues ranging from black to white. Although we may suspect light aquatinting in some areas, no aquatint has been used in this etching.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Bell Hammer, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1976. The image and composition of this miniature work would have looked quite spectacular as one of Tanaka’s much larger works. The angle of observation is daring as we look up into the roof of a bell tower with a very large bronze bell. The bell hammer is actually a tree trunk and is suspended on the outside of the bell. It produces a low tone and a deep resonance that can be heard many miles away. In this image, the straight lines of the suspension ropes, which indicate the tension of the heavy weight of the hammer, run perpendicular to beams of the inner roof structure. However Tanaka purposefully off-centred the composition of the bell and the hammer to avoid a stark symmetrical grid, creating an appealing and natural image.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Bell Hammer, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1976. The image and composition of this miniature work would have looked quite spectacular as one of Tanaka’s much larger works. The angle of observation is daring as we look up into the roof of a bell tower with a very large bronze bell. The bell hammer is actually a tree trunk and is suspended on the outside of the bell. It produces a low tone and a deep resonance that can be heard many miles away. In this image, the straight lines of the suspension ropes, which indicate the tension of the heavy weight of the hammer, run perpendicular to beams of the inner roof structure. However Tanaka purposefully off-centred the composition of the bell and the hammer to avoid a stark symmetrical grid, creating an appealing and natural image.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Veranda No. 1, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1976. This is one of Tanaka’s more radical compositions. From early in his career, the artist has taken pleasure in the rendering of woodgrain. His unmatched technique enabled him to produce a finished copper plate with a structure resembling that of weathered wood. In earlier works the artist used a combination of line etching and aquatint to give wooden posts and beams an aged look. In this large etching, however, the grain of the veranda boards was entirely line etched.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Veranda No. 1, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1976. This is one of Tanaka’s more radical compositions. From early in his career, the artist has taken pleasure in the rendering of woodgrain. His unmatched technique enabled him to produce a finished copper plate with a structure resembling that of weathered wood. In earlier works the artist used a combination of line etching and aquatint to give wooden posts and beams an aged look. In this large etching, however, the grain of the veranda boards was entirely line etched.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Sekigahara Snow, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1976. Following a few early etchings of snow scenes, snow would become a recurring subject in Tanaka’s oeuvre and a popular theme among his collectors. Except for the faintest shadows in the snow, which have been stippled with the needle and very briefly brushed with the mordant, the plate is line etched in an infinite array of textures. It should be noticed that in fact more than two thirds of the surface of the plate was left untouched to print blank: the white of the paper depicts the snow. The area of Sekigahara is notorious for heavy snowfall.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Sekigahara Snow, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1976. Following a few early etchings of snow scenes, snow would become a recurring subject in Tanaka’s oeuvre and a popular theme among his collectors. Except for the faintest shadows in the snow, which have been stippled with the needle and very briefly brushed with the mordant, the plate is line etched in an infinite array of textures. It should be noticed that in fact more than two thirds of the surface of the plate was left untouched to print blank: the white of the paper depicts the snow. The area of Sekigahara is notorious for heavy snowfall.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Wall No. 3, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1976. Wall No. 3 is one of Tanaka’s boldest compositions. The cobweb visible in the open doorway at the top left of the darkly aquatinted section of the etching gives the impression that the building has fallen into disuse. Great skill is required to wipe and print this part without producing smudges on the thin white lines of the cobweb.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Wall No. 3, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1976. Wall No. 3 is one of Tanaka’s boldest compositions. The cobweb visible in the open doorway at the top left of the darkly aquatinted section of the etching gives the impression that the building has fallen into disuse. Great skill is required to wipe and print this part without producing smudges on the thin white lines of the cobweb.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Persimmons and Roofs No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1975. The viewer is in an elevated position looking down from a hill or a mountain slope onto the roofs of two thatched farmhouses and a persimmon tree beyond. The apparent proximity of the lighter foliage in the left foreground gives the impression of the image having been taken and cropped with the foreshortening qualities of a photographic tele lens. This very aspect together with the vertical image of this etching is strongly reminiscent of the tradition of Japanese scroll paintings, particularly those of landscapes that often seem to be seen from some elevation and show an almost telephoto-like vantage point. Yet both the elevated angle and this point of view is quite rare in Tanaka’s oeuvre. Although the official reading also mentions the use of aquatint, in fact the entire plate is needle etched with only a small area of aquatint in the triangle of the roof gable with its ventilation opening.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Persimmons and Roofs No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1975. The viewer is in an elevated position looking down from a hill or a mountain slope onto the roofs of two thatched farmhouses and a persimmon tree beyond. The apparent proximity of the lighter foliage in the left foreground gives the impression of the image having been taken and cropped with the foreshortening qualities of a photographic tele lens. This very aspect together with the vertical image of this etching is strongly reminiscent of the tradition of Japanese scroll paintings, particularly those of landscapes that often seem to be seen from some elevation and show an almost telephoto-like vantage point. Yet both the elevated angle and this point of view is quite rare in Tanaka’s oeuvre. Although the official reading also mentions the use of aquatint, in fact the entire plate is needle etched with only a small area of aquatint in the triangle of the roof gable with its ventilation opening.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Wind, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and lift-ground aquatint 1976. The withering blast of the storm can almost be felt. Tanaka indicates the movements of the tempestuous air by applying an almost calligraphic wash of sugar-lift aquatint to the sky, which is only shallowly etched. The storm is literally blowing the building apart. Except for the shallow aquatint in the sky section, the plate is entirely line etched and drawn with so much virtuosity that parts of the thatch actually seem to be in motion, the straw on the collapsed rooftop fluttering in the wind.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Wind, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and lift-ground aquatint 1976. The withering blast of the storm can almost be felt. Tanaka indicates the movements of the tempestuous air by applying an almost calligraphic wash of sugar-lift aquatint to the sky, which is only shallowly etched. The storm is literally blowing the building apart. Except for the shallow aquatint in the sky section, the plate is entirely line etched and drawn with so much virtuosity that parts of the thatch actually seem to be in motion, the straw on the collapsed rooftop fluttering in the wind.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Thatched Roof by Night, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1975. In this print, the second in a series of bold architectural compositions following Collapsing Roof No. 4, the artist makes clever use l of the aquatint technique for the dark section I forming the sky. That blackness and the deep | shadow underneath the eaves accentuate the light of the (invisible) cold autumn or winter moon shining on the roof and the plumes of I the miscanthus grass (susuki) in the foreground. The regular spacing of the vertical bearers in the walls of the house and the shed subtly emphasize the square dimensions of the image, a size and format favored by the artist.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Thatched Roof by Night, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1975. In this print, the second in a series of bold architectural compositions following Collapsing Roof No. 4, the artist makes clever use l of the aquatint technique for the dark section I forming the sky. That blackness and the deep | shadow underneath the eaves accentuate the light of the (invisible) cold autumn or winter moon shining on the roof and the plumes of I the miscanthus grass (susuki) in the foreground. The regular spacing of the vertical bearers in the walls of the house and the shed subtly emphasize the square dimensions of the image, a size and format favored by the artist.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Mountain Houses, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1975. This is the third of three masterly modest little etchings produced in the spring and early summer of 1975. In this print Tanaka uses aquatint techniques in combination with line etching to depict the trees on the mountainside with superior virtuosity. The structures and textures of the weathered roofs of the farmhouses naturally fuse with the foliage of the surrounding trees.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Mountain Houses, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1975. This is the third of three masterly modest little etchings produced in the spring and early summer of 1975. In this print Tanaka uses aquatint techniques in combination with line etching to depict the trees on the mountainside with superior virtuosity. The structures and textures of the weathered roofs of the farmhouses naturally fuse with the foliage of the surrounding trees.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Collapsing Roof No. 4, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1975. Collapsing Roof no. 4 represents the artist’s first use of this particular large square format for a purely architectural subject. The plate is entirely ine etched and has deeply bitten cross-hatching in the darkest sections as well as very fine lines on the right where the thatch seems to dissolve into the sky beyond. A masterpiece of etching.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Collapsing Roof No. 4, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1975. Collapsing Roof no. 4 represents the artist’s first use of this particular large square format for a purely architectural subject. The plate is entirely ine etched and has deeply bitten cross-hatching in the darkest sections as well as very fine lines on the right where the thatch seems to dissolve into the sky beyond. A masterpiece of etching.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Trees No. 3, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1974. This print, depicting a dormant orchard in winter, is completely line etched. The shapes of the branches, the contrasts they present, and the sense of distance to the trees in the background are entirely achieved through patient drawing with the etching needle and careful timing of the consecutive biting sessions. If we compare this print to Winter Orchard of only seven years earlier ( 5), we find that Tanaka had by now reached the high technical level he would maintain in the years to come.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Trees No. 3, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1974. This print, depicting a dormant orchard in winter, is completely line etched. The shapes of the branches, the contrasts they present, and the sense of distance to the trees in the background are entirely achieved through patient drawing with the etching needle and careful timing of the consecutive biting sessions. If we compare this print to Winter Orchard of only seven years earlier ( 5), we find that Tanaka had by now reached the high technical level he would maintain in the years to come.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Village at Dusk, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024.Color etching, 1974. Whereas in the majority of the artist’s landscapes mountains are a combination of line etching and aquatint, in this work the blue and the black plate were entirely drawn with the etching needle. Skillful variation in the cross-hatching gives the forested mountainside its apparent structure. The flower is a higanbana (red spider lily or Lycoris radiata), which flowers at the end of summer. In Japan it is associated with final farewells. According to Buddhist belief it is the flower of passing and rebirth and therefore often used at funerals. The suggestion of evening twilight and the tonality of the blue ink, rarely used in Tanaka’s etchings, add to the melancholic atmosphere.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Village at Dusk, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024.Color etching, 1974. Whereas in the majority of the artist’s landscapes mountains are a combination of line etching and aquatint, in this work the blue and the black plate were entirely drawn with the etching needle. Skillful variation in the cross-hatching gives the forested mountainside its apparent structure. The flower is a higanbana (red spider lily or Lycoris radiata), which flowers at the end of summer. In Japan it is associated with final farewells. According to Buddhist belief it is the flower of passing and rebirth and therefore often used at funerals. The suggestion of evening twilight and the tonality of the blue ink, rarely used in Tanaka’s etchings, add to the melancholic atmosphere.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Roofs of Hida No. 5, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1974. Although people rarely appear in Tanaka’s etchings, human presence is frequently felt. This may have to do with the fact that in rural Japan farmhouses, and sometimes entire villages, often seem quite deserted. Moreover, since the artist lacked formal training in figure studies, he was probably not comfortable with depicting people. This is a rare and successful attempt. The stooping figure of the woman, possibly planting rice seedlings, dominates the image. Her hat and scarf protect her from what seems to be harsh sunlight.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Roofs of Hida No. 5, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1974. Although people rarely appear in Tanaka’s etchings, human presence is frequently felt. This may have to do with the fact that in rural Japan farmhouses, and sometimes entire villages, often seem quite deserted. Moreover, since the artist lacked formal training in figure studies, he was probably not comfortable with depicting people. This is a rare and successful attempt. The stooping figure of the woman, possibly planting rice seedlings, dominates the image. Her hat and scarf protect her from what seems to be harsh sunlight.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Collapsing Roof No. 3, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1973. In this print, the thick, black oil-based etching ink has congealed and dried in a matte black finish The darker lines, particularly in the weeds in the foreground and some of the darker textures of the roof, are etched so deeply that if one could run one’s fingers across them, they would be ‘readable’ like Braille. The print is a variation on Tanaka’s earlier Spring is Near and the combination of bare trees and stark thatched roofs would occasionally return in his work.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Collapsing Roof No. 3, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1973. In this print, the thick, black oil-based etching ink has congealed and dried in a matte black finish The darker lines, particularly in the weeds in the foreground and some of the darker textures of the roof, are etched so deeply that if one could run one’s fingers across them, they would be ‘readable’ like Braille. The print is a variation on Tanaka’s earlier Spring is Near and the combination of bare trees and stark thatched roofs would occasionally return in his work.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Roofs of Hida No. 4, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, printed in sepia on chine collé, 1973. Hida is the northernmost region in the prefecture of Gifu, close to Japan’s Northern Alps. In the early 1970s Tanaka made various trips to this region to record its characteristic multi-storied thatched farmhouses, some of which were already deserted. Roofs of Hida no. 4 is one of Tanaka’s most playful prints: from behind the half-opened sliding door of a farmhouse, we look towards another, obviously deserted, farmhouse with torn paper window screens. The dark aquatint section on the right contrasts sharply with the sunlit farmhouse opposite, evoking a surrealistic atmosphere, the sense that the whole village is, in fact, deserted. In the left section Tanaka Has applied the technique of chine collé. Each single piece of the wafer-thin gampi paper had to be cut and torn separately to provide a realistic image0 the damaged paper of the sliding door. Therefore no two prints in this edition are identical.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Roofs of Hida No. 4, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, printed in sepia on chine collé, 1973. Hida is the northernmost region in the prefecture of Gifu, close to Japan’s Northern Alps. In the early 1970s Tanaka made various trips to this region to record its characteristic multi-storied thatched farmhouses, some of which were already deserted. Roofs of Hida no. 4 is one of Tanaka’s most playful prints: from behind the half-opened sliding door of a farmhouse, we look towards another, obviously deserted, farmhouse with torn paper window screens. The dark aquatint section on the right contrasts sharply with the sunlit farmhouse opposite, evoking a surrealistic atmosphere, the sense that the whole village is, in fact, deserted. In the left section Tanaka Has applied the technique of chine collé. Each single piece of the wafer-thin gampi paper had to be cut and torn separately to provide a realistic image0 the damaged paper of the sliding door. Therefore no two prints in this edition are identical.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Two Thatched Roofs No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1973. Although modest in size and subject, this work eminently represents Tanaka’s artistic and graphic qualities: a sober composition with an elevated foreshortened view, executed in simple line etching with a courageous use of various drawing and biting techniques. The rough, deep cross- hatching of the sharp cut-offs of the reeds in the foreground roof contrasts almost tangibly with the soft, finely etched layers of the thatch. The shadows of the overhanging rooflines were not achieved by aquatinting, but by densely cross-hatched line etching.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Two Thatched Roofs No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1973. Although modest in size and subject, this work eminently represents Tanaka’s artistic and graphic qualities: a sober composition with an elevated foreshortened view, executed in simple line etching with a courageous use of various drawing and biting techniques. The rough, deep cross- hatching of the sharp cut-offs of the reeds in the foreground roof contrasts almost tangibly with the soft, finely etched layers of the thatch. The shadows of the overhanging rooflines were not achieved by aquatinting, but by densely cross-hatched line etching.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Trees No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1974. Careful studies of trees regularly turn up in Tanaka’s work. Trees No. 2 is a large and ambitious etching. The roots, trunk and branches are entirely done in cross-hatched line etching. The large tree, now in a bad condition, stands just outside the compound of Shōren-in, adjacent to the Chion-in, in Kyoto’s Higashiyama-Sanjo district. It has inspired many a Kyoto artist.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Trees No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching, 1974. Careful studies of trees regularly turn up in Tanaka’s work. Trees No. 2 is a large and ambitious etching. The roots, trunk and branches are entirely done in cross-hatched line etching. The large tree, now in a bad condition, stands just outside the compound of Shōren-in, adjacent to the Chion-in, in Kyoto’s Higashiyama-Sanjo district. It has inspired many a Kyoto artist.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Okinawa Roofs, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1974. In 1973 Tanaka had a solo exhibition at the Okinawa Hilton Hotel. Okinawa Roofs shows the local style of roof covering, where tiles are fixed with mortar to prevent them from flying off during the tropical typhoons that annually rage across Japan’s southernmost sub-archipelago. Between the cross-hatched sections of the sturdy tiled roofs, the finely etched leaves of a tropical banana palm add a subtle touch of local vegetation.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Okinawa Roofs, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1974. In 1973 Tanaka had a solo exhibition at the Okinawa Hilton Hotel. Okinawa Roofs shows the local style of roof covering, where tiles are fixed with mortar to prevent them from flying off during the tropical typhoons that annually rage across Japan’s southernmost sub-archipelago. Between the cross-hatched sections of the sturdy tiled roofs, the finely etched leaves of a tropical banana palm add a subtle touch of local vegetation.

Enlarged version of one of the exhibitted etchings in the exhibition hall.

Enlarged version of one of the exhibitted etchings in the exhibition hall.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Snowbird, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 2008. Tanaka was 75 years old when he created this powerful print. A lone crow endures the heavy snowfall with no apparent interest in a last overripe persimmon left on the tree according to custom. The etching gives the impression of having been printed from two separate plates: one with the deeply bitten and densely drawn branches of the tree in black, and a second aquatinted plate inked in gray. The entire image, however, was etched and printed using one single plate. The artist mixed four different inks in order to achieve the combination of an intense black in the deeper groves of the silhouetted tree and the crow, and the warm gray tone for the shallowly bitten aquatinted sky. The persimmon is hand painted-in.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Snowbird, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 2008. Tanaka was 75 years old when he created this powerful print. A lone crow endures the heavy snowfall with no apparent interest in a last overripe persimmon left on the tree according to custom. The etching gives the impression of having been printed from two separate plates: one with the deeply bitten and densely drawn branches of the tree in black, and a second aquatinted plate inked in gray. The entire image, however, was etched and printed using one single plate. The artist mixed four different inks in order to achieve the combination of an intense black in the deeper groves of the silhouetted tree and the crow, and the warm gray tone for the shallowly bitten aquatinted sky. The persimmon is hand painted-in.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Momiji Daimon-ji, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 2007. Daimon-ji is an old well-known Buddist temple from the Shingon sect in Ibaraki City in Osaka prefecture and very close to Tanaka’s home. The artist was already 74 years of age when he etched and also printed the entire edition of this large work from two separate plates. The most important sculpture in this temple is the Bosatsu Sho Nyoirin Kanzeon Bodhisattva which was carved in the Heian period (794-1185) and is designated as an important national cultural property. The complex can be entered through a small gate at the top of a steep ten-step stone stairs and in autumn boasts richly coloured red maples. Tanaka took some artistic liberties in this print by leaving out the old timber door in the wall on the immediate left of the gate as it would have distracted from the serenity of the image.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Momiji Daimon-ji, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 2007. Daimon-ji is an old well-known Buddist temple from the Shingon sect in Ibaraki City in Osaka prefecture and very close to Tanaka’s home. The artist was already 74 years of age when he etched and also printed the entire edition of this large work from two separate plates. The most important sculpture in this temple is the Bosatsu Sho Nyoirin Kanzeon Bodhisattva which was carved in the Heian period (794-1185) and is designated as an important national cultural property. The complex can be entered through a small gate at the top of a steep ten-step stone stairs and in autumn boasts richly coloured red maples. Tanaka took some artistic liberties in this print by leaving out the old timber door in the wall on the immediate left of the gate as it would have distracted from the serenity of the image.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Remaining Persimmons, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 2005. By now in his early seventies, Tanaka would continue to create large etchings, sometimes with a second plate for colour. The needle-drawn lines become more effective and are lightly bitten, adding to the crispness of the image. In this work, as always printed by the artist himself in an edition of 100 plus ten artist proofs- all immaculately wiped and printed - Tanaka used a second plate for the orange persimmons. This means inking and wiping rather large plates 220 times and running them through the press in perfect registration.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Remaining Persimmons, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 2005. By now in his early seventies, Tanaka would continue to create large etchings, sometimes with a second plate for colour. The needle-drawn lines become more effective and are lightly bitten, adding to the crispness of the image. In this work, as always printed by the artist himself in an edition of 100 plus ten artist proofs- all immaculately wiped and printed - Tanaka used a second plate for the orange persimmons. This means inking and wiping rather large plates 220 times and running them through the press in perfect registration.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Harvest Season No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1984. Yamada Tetsuo, the primary dealer of Tanaka’s work in the 1970 and 1980-s and the publisher of the first three catalogue raisonnés, included this etching in the colour-etching section of the 1963-1990 raisonne. The clever use of both rather deeply bitten line etching and aquatint in combination with the very finely applied and briefly bitten aquatint in the -still unharvested - rice underneath the stone wall as well in the bamboo and the trees behind the farm buildings indeed gives the impression that this etching was printed of two separate plates. However only one plate was used and while the deeper line-bitten sepia ink after the wiping of the plate shows up much darker, as in the lines of the wooded poles holding up the drying racks and the tree foliage around the hamlet, the same ink leaves a warmer hue in the thinly bitten aquatint sections in the fields in front and the tress behind the farmhouses.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Harvest Season No. 2, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1984. Yamada Tetsuo, the primary dealer of Tanaka’s work in the 1970 and 1980-s and the publisher of the first three catalogue raisonnés, included this etching in the colour-etching section of the 1963-1990 raisonne. The clever use of both rather deeply bitten line etching and aquatint in combination with the very finely applied and briefly bitten aquatint in the -still unharvested - rice underneath the stone wall as well in the bamboo and the trees behind the farm buildings indeed gives the impression that this etching was printed of two separate plates. However only one plate was used and while the deeper line-bitten sepia ink after the wiping of the plate shows up much darker, as in the lines of the wooded poles holding up the drying racks and the tree foliage around the hamlet, the same ink leaves a warmer hue in the thinly bitten aquatint sections in the fields in front and the tress behind the farmhouses.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Backlit Landscape, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1985. In this print, the rice has apparently been harvested some months ago. The sky is crisp and clear. Judging from the shadows on the road and the roof of the farmhouse, the sun shines at a low angle. It is early spring.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Backlit Landscape, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1985. In this print, the rice has apparently been harvested some months ago. The sky is crisp and clear. Judging from the shadows on the road and the roof of the farmhouse, the sun shines at a low angle. It is early spring.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Okusaga, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1986. Okusaga or Inner-Saga, is an area to the west of Kyoto, famous for its natural beauty. It is a much-loved hiking destination in autumn. Quite a few traditional buildings have survived in this semi-rural village, and the City of Kyoto has designated part of the area as one of four Traditional Structure Conservation Districts. One has to examine the actual print to be able to appreciate the subtlety of atmosphere in this work. The shōji (sliding door) is open; the mood is intimate, inviting. The line-etching techniques are richly varied, and the partly burnished aquatints in the windows of the shed give a convincing rendition of pre-war soda-lime glass panes.

Tanaka Ryōhei, Okusaga, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1986. Okusaga or Inner-Saga, is an area to the west of Kyoto, famous for its natural beauty. It is a much-loved hiking destination in autumn. Quite a few traditional buildings have survived in this semi-rural village, and the City of Kyoto has designated part of the area as one of four Traditional Structure Conservation Districts. One has to examine the actual print to be able to appreciate the subtlety of atmosphere in this work. The shōji (sliding door) is open; the mood is intimate, inviting. The line-etching techniques are richly varied, and the partly burnished aquatints in the windows of the shed give a convincing rendition of pre-war soda-lime glass panes.

Tanaka Ryōhei, The Snow Stopped, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1986. All areas except for the sky, a tiny section around the footprints in the snow, and a finely aquatinted area on the flank of the roof are line teched. Tanaka created a mood that only he could achieve in etching. This print demonstrates his careful observation of the atmosphere. The sky seems to become lighter as if the clouds are about lift. The diffuse light is reflected in the fresh wet snow. Unlike his more dramatic etchings, this print has no sharp shadows or contrasts - it may look deceptively dull at first sight.

Tanaka Ryōhei, The Snow Stopped, from the exhibition ‘From Line to Landscape’ at the Museum für ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Dec 2024. Etching and aquatint, 1986. All areas except for the sky, a tiny section around the footprints in the snow, and a finely aquatinted area on the flank of the roof are line teched. Tanaka created a mood that only he could achieve in etching. This print demonstrates his careful observation of the atmosphere. The sky seems to become lighter as if the clouds are about lift. The diffuse light is reflected in the fresh wet snow. Unlike his more dramatic etchings, this print has no sharp shadows or contrasts - it may look deceptively dull at first sight.