Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · gallery view · page 1/5

Emakimono: The art of Japanese handscrolls

Emakimono, or Japanese handscrolls, are a captivating form of narrative art that emerged during the Heian period (794-1185 AD). These exquisite scrolls combine text and pictures to tell stories, document courtly life, or illustrate poetic themes. The format allows for sequential viewing, where the story unfolds as the scroll is gradually unrolled from right to left, offering a unique and intimate artistic experience. In this post, we explore the history, techniques, and cultural significance of emakimono in Japanese art and literature.

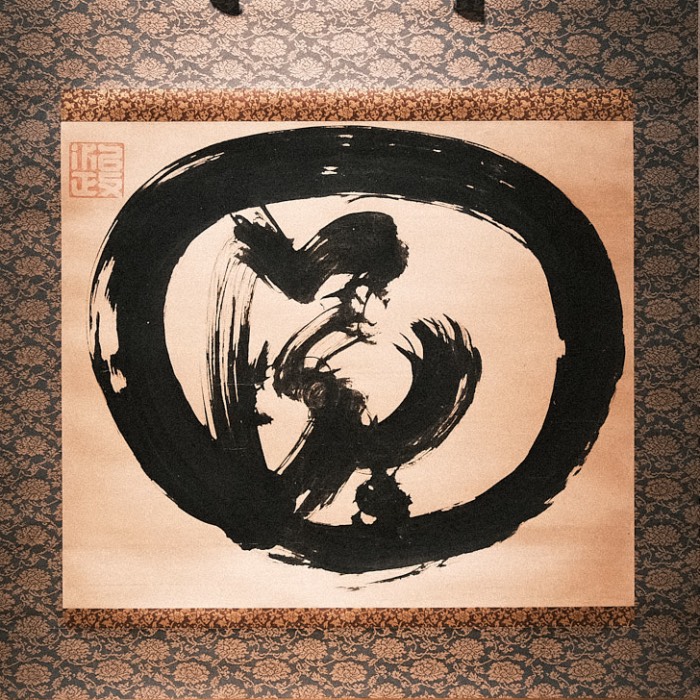

Kakemono: The art of Japanese hanging scrolls

Kakemono, or Japanese hanging scrolls, are a prominent feature in the traditional Japanese art landscape. These scrolls are designed to be displayed vertically and are often used to adorn the alcoves of Japanese homes, particularly in settings like the tea ceremony. The art of kakemono centers around the aesthetics of simplicity and seasonal change, making it a dynamic element of Japanese decor. In this post, we briefly explore the history and significance of kakemono in Japanese art and culture.

Exploring Buddhist and East Asian art in Cologne

Cologne, a city rich in Christian history and culture, also offers a unique opportunity for enthusiasts of Buddhist and East Asian art. The city is home to two remarkable institutions: the Museum of East Asian Art and the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum. Here some of my favorite pieces from both museums.

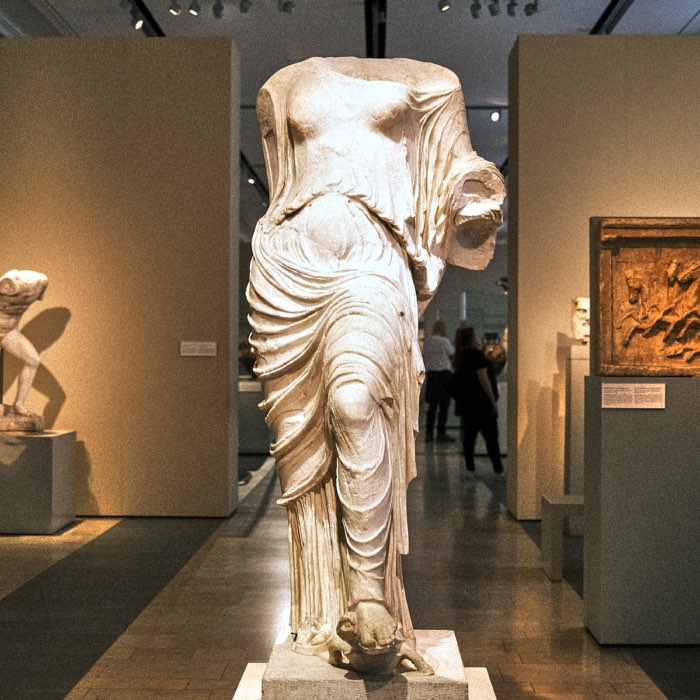

On the Hellenistic heritage in Christian culture and Buddhist art

My recent museum visits and studies have revealed that the perceived differences between various cultures and historical periods are not as pronounced as I once believed. Contrary to the simplified narratives taught in school, the Greco-Roman heritage did not vanish after the fall of the Roman Empire but transformed and adapted into new cultural contexts. This influence extended beyond the Christian culture of the Middle Ages to include the Buddhist art of the Gandhara style. In this post, I will summarize my findings and share my thoughts on this topic.

Lares and the evolution of household deities in Europe

During my visit to the Roman-Germanic Museum in Cologne, I stumbled upon intriguing small deity figures, which piqued my curiosity. Upon further research, I discovered they were representations of Roman Lares, ancient household deities. This discovery led me to draw some parallels with later religious practices, including those found in Eastern traditions.

Cologne’s history through a magnifying glass: The city museum

After a long time of closure, the Cologne City Museum reopened its doors in March 2024. The museum, which is now temporarily housed in the former Franz Sauer fashion house, has a large collection of around 350,000 objects spanning from the Middle Ages to the present day. The exhibits cover a wide range of topics, including paintings, graphics, militaria, coins, textiles, furniture, and everyday objects. The museum’s current concept focuses on showcasing a small selection of objects that are presented in an emotional context, offering a unique perspective on societal and historical issues. In my opinion, in this way the museum actually serves as a lens through which visitors can explore the history of 2000-year-old Cologne.

From Roman temple to Christian sanctuary: The historical evolution of St. Maria im Kapitol in Cologne

Standing proudly amidst the historic cityscape of Cologne, St. Maria im Kapitol is more than just a place of worship. It’s a witness to the layers of history that have shaped the city over centuries. At its core lies a rich narrative that traces back to ancient Roman times, where a temple once dedicated to the Capitoline Triad stood. The history of this temple exemplifies how ancient buildings were not simply erased but repurposed and altered over time. It illustrates that the ancient world did not vanish overnight. Instead, it was transformed and integrated into the medieval and modern eras, challenging the image of sharp epochal changes and highlighting a continuous development of cultural and architectural heritage.

Cologne’s pottery heritage

Besides its glass production, Cologne also had a relevant ceramic production. During the reign of Augustus, from 27 BC to 14 AD, Cologne began to emerge as a notable center for pottery production. This period marked the initial steps of the city in establishing its reputation in the craft of ceramics

Roman legacy of glass art in Cologne

Cologne not only has a rich Roman heritage, but also a (perhaps) lesser-known history of glassmaking. Archaeological finds in the city have revealed a rich heritage of glass art, encompassing everything from drinking vessels to jewelry and decorative objects. And the Roman-Germanic Museum houses a significant collection of these artifacts. Here are some of my favorite pieces that I have photographed during my visit.

Roman legacy in Cologne

I recently visited the Roman-Germanic Museum in Cologne, that exhibits archeological finds from the Roman and Germanic era in Cologne and the surrounding area. While strolling through the exhibition, I was fascinated by the acute presence of the artifacts on display and the stories behind them. Of course, I’m aware of Cologne’s Roman heritage, but every visit to the museum makes me even more aware of the Roman influence on Cologne’s culture and identity.