Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 1/52

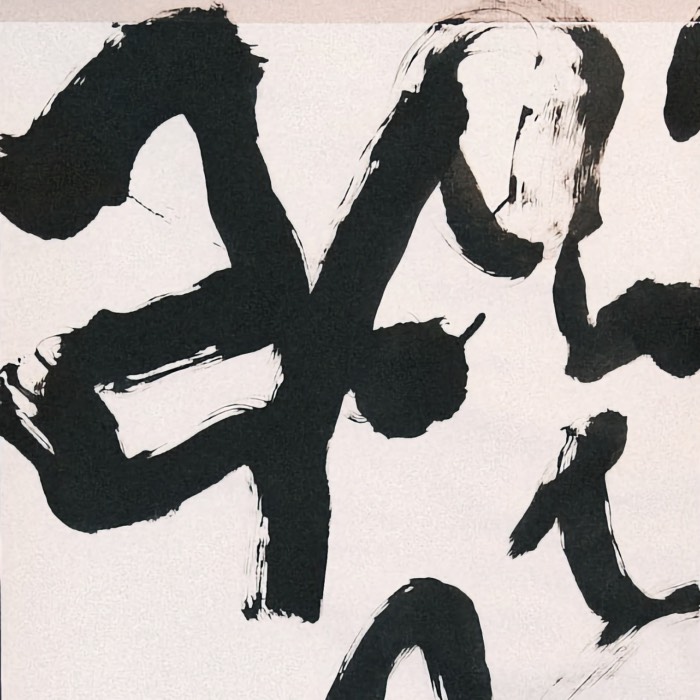

Calligraphic aspects in Korean art

In parallel to the larger exhibitions, the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln presented the small special display The Line, dedicated to calligraphic principles in Korean art. Though compact in scale, the exhibition addressed a foundational aspect of Korean visual culture: The role of writing and brushwork as a unifying aesthetic principle across media. Thus, a fitting complement to the main show on Jianfeng Pan Ink Roamings we explored in the previous post.

Jianfeng Pan: An ink wanderer between cultures

In April 2025, I visited the exhibition Ink Roamings. Contemporary works on paper by Jianfeng Pan (2014–2024) at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln. The exhibition presented around sixty works on paper produced over the past decade by the Chinese ink artist Jianfeng Pan (b. 1973), ranging from monumental hanging scrolls to small album formats and serial works. In this post, I summarize what I have seen and learned from the exhibition.

From line to landscape: Tanaka Ryōhei and the quiet radicalism of etching

I was lucky to visit the exhibition From Line to Landscape at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln (Museum of East Asian Art in Cologne) in December 2024. The show focused on the work of Tanaka Ryōhei (1933–2019) and offered a rare opportunity to see a comprehensive selection of his etchings spanning more than five decades. In this post, I summarize what I have learned and seen from the exhibition.

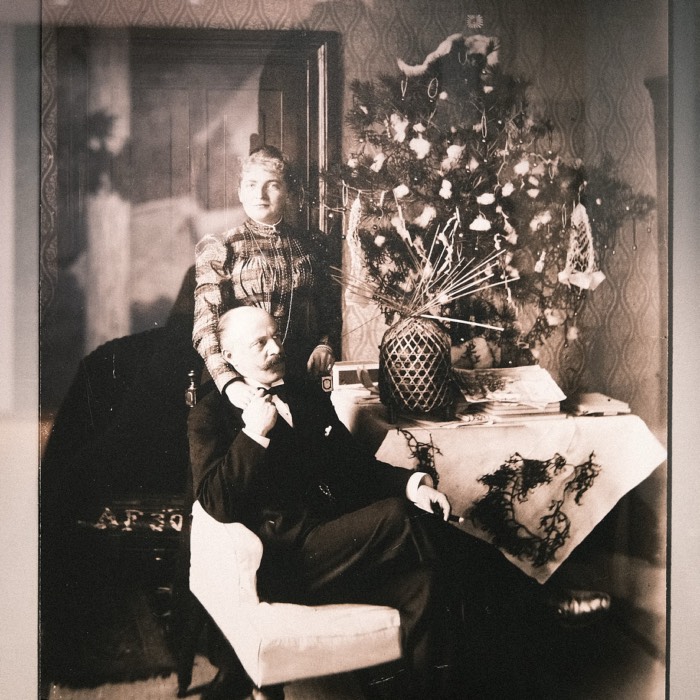

Frieda and Adolf Fischer and the origins of the Museum of East Asian Art in Cologne

How did a city like Cologne come to host a major museum of East Asian art? In October 2024, I visited the exhibition Expeditions – travelogues and photographs by the museum founders 1897–1899 at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln (Museum of East Asian Art in Cologne). The exhibition reconstructed the journeys of Frieda and Adolf Fischer, the founders of the museum, to Japan and Taiwan at the turn of the 20th century. In this post, I summarize some of the key points from the exhibition and reflect on the historical context of the founding of the museum.

Martin Parr (1952–2025)

When I read that Martin Parr had died on December 6, 2025, I was personally affected. Parr, who revolutionized documentary photography with his distinctive style and critical eye, was not a just a figure for me, but someone whose work had accompanied my own way into photography for many years. Long before I had a clear sense of what kind of photographs I wanted to take, his images shaped how I looked at everyday life, at leisure, consumption, and the small, awkward rituals people perform without noticing themselves. His death marked the loss not just of an influential photographer, but of a perspective that had quietly challenged how photography could observe the ordinary. In this post, I’d like to reflect on Parr’s influence on photography and share some personal thoughts about his work.

Gregory Crewdson Retrospective

On the same day I visited From Dawn Till Dusk, I also saw the Gregory Crewdson retrospective at the Kunstmuseum Bonn. Initially skeptical of his heavily staged photography, I ended up deeply impressed by how many small narratives unfold within each large-format image and by the extraordinary quality of the prints. In this post, I share a few reflections and photos from the exhibition.

From Dawn Till Dusk: Shadows and light at the Kunstmuseum Bonn

In October 2025, I visited From Dawn Till Dusk. Der Schatten in der Kunst der Gegenwart at the Kunstmuseum Bonn. The exhibition presented shadow as an image-producing element in its own right, ranging from historical references to contemporary installations. I liked the playful and surprising ways shadow was used in the artworks. Here are some photos from the visit.

The Bonnefanten Museum: Curating sacred and secular art in a modern architectural space

On the same day I visited the Basilica of St. Servatius, I spent several hours at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht. Experiencing both places in immediate succession made it clear to me that sacred and secular spaces are not opposites, but different ways of structuring attention, meaning, and presence. This post reflects on how architecture, display, and framing shape perception across religious and modern cultural institutions.

The Basilica of St. Servatius as a symbol of the complexity of European cultural heritage

I visited the Basilica of St. Servatius in Maastricht in August 2025 without a plan and without the ambition to decode Romanesque art. The building simply drew my attention. Inside, what stayed with me was not a single object, but how the space itself shapes behavior: scarce light, lingering sound, thresholds that slow you down before you notice you have slowed down. The basilica feels like an accumulation rather than a finished statement. Sacredness here is not an invisible property. It is learned, reinforced, and maintained through architecture, story, and repeated use. And yet, the quietest stillness I found was not in the nave, but in the cloister, where nothing demands attention and meaning is allowed to arise or dissolve. In this post, I share some reflections and images from that visit.

How languages begin and vanish: A short follow-up to our series on language and writing systems

Almost exactly one year ago, I wrote a short series on the origins of languages and writing systems. In that series, we explored how writing systems emerged from earlier forms of communication, how they shaped human history, and how different cultures developed their own unique scripts. A recent documentary on Arte addressed the question of whether all humans once shared a single ancestral language. An interesting topic and I thought that it would be an ideal opportunity to return to this subject. In this post I therefore summarize and discuss the main points of the documentary, which continues the themes from last year’s series, but examines them from a different angle. Here, the focus is on spoken language itself: how humans create new forms of communication, how languages evolve, and how easily many of them vanish. Thus, this time we shift from writing systems back to the spoken languages that underlie them.