Calligraphic aspects in Korean art

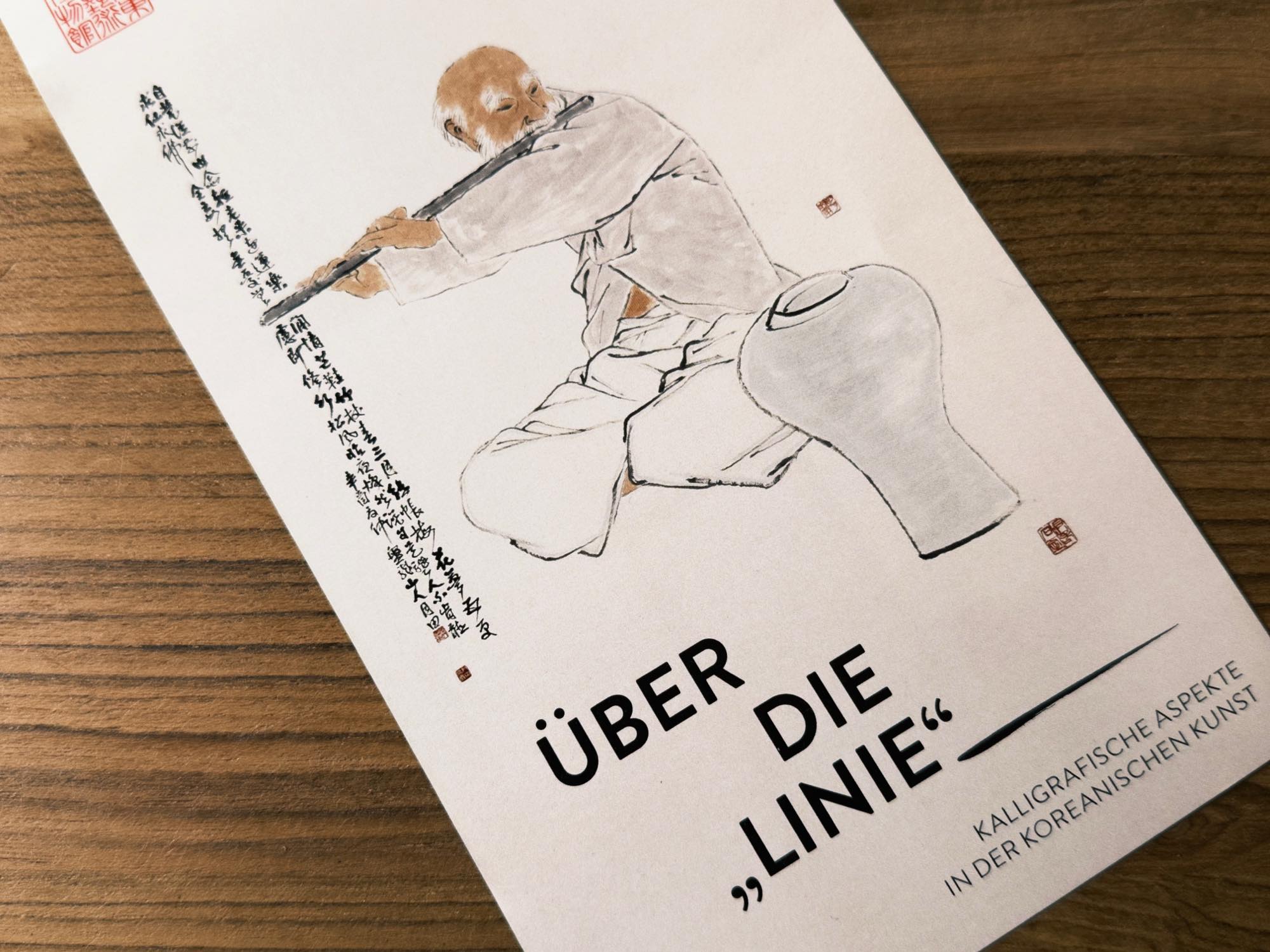

In parallel to the larger exhibitions, the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln presented the small special display The Line in April 2025, dedicated to calligraphic principles in Korean art. Though compact in scale, the exhibition addressed a foundational aspect of Korean visual culture: The role of writing and brushwork as a unifying aesthetic principle across media. Thus, a fitting complement to the main show on Jianfeng Pan Ink Roamings we explored in the previous post.

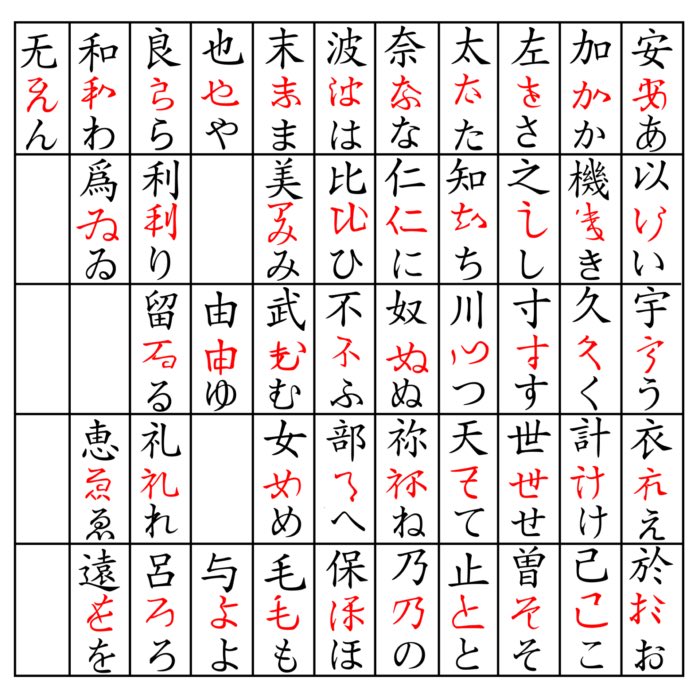

Characters of the Korean Phonetic Script, Ven. Mun Suan, Ink on paper, Korea, dated 1989. Read more about this series below.

Characters of the Korean Phonetic Script, Ven. Mun Suan, Ink on paper, Korea, dated 1989. Read more about this series below.

Writing and calligraphy in Korea

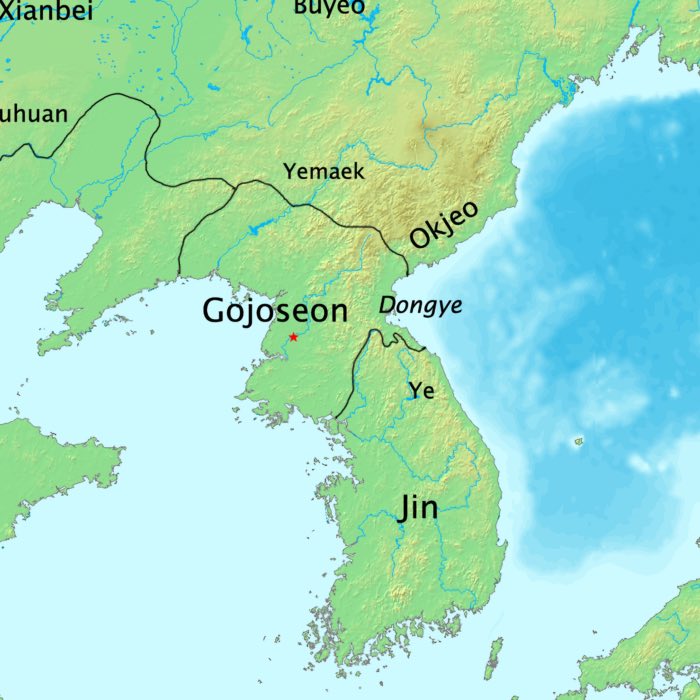

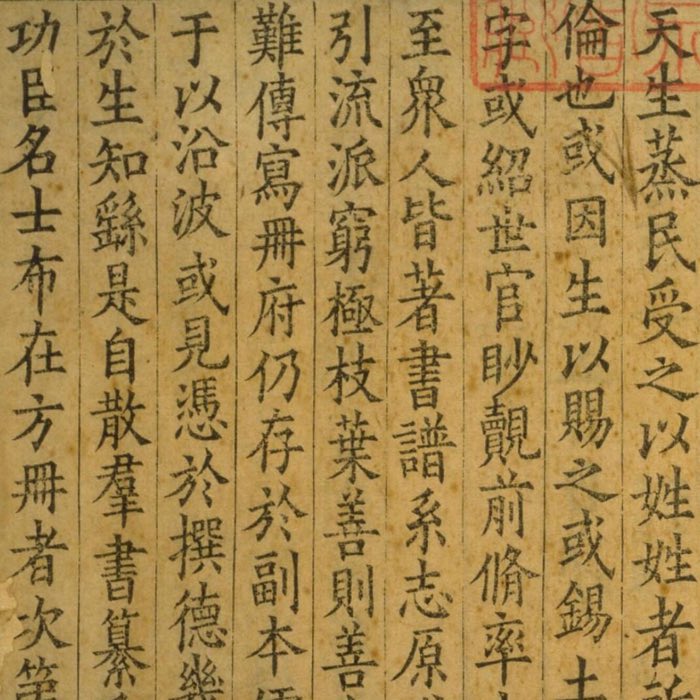

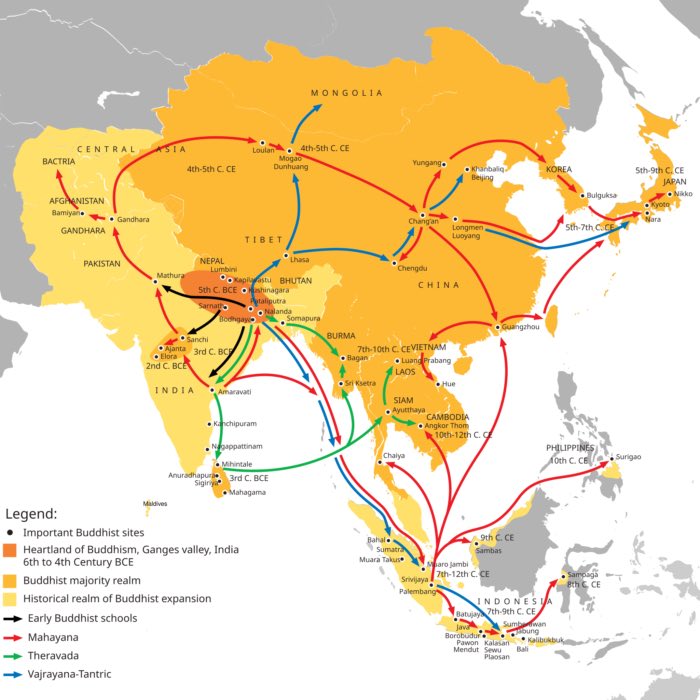

Writing and calligraphy (Korean: seoye) have occupied a central position in Korean art since the early adoption of the Chinese writing system (hanja)[^1] from the 1st century onward. Mastery of this script was traditionally associated with officials and scholars, for whom calligraphy was both an intellectual discipline and an artistic practice.

Note: While chinese characters are called hanzi (漢字) in Chinese, they are referred to as hanja (한자 / 漢字) in Korean and kanji (漢字) in Japanese.

From the 15th century, this landscape changed significantly with the introduction of the phonetic script hangeul, developed under the reign of King Sejong (r. 1418–1459). Its relative simplicity enabled broader access to literacy, including women and members of lower social strata such as the nobi (slave) class. The coexistence of hanja and hangeul introduced different visual rhythms and stroke structures into Korean writing culture, both traditionally executed with brush and ink.

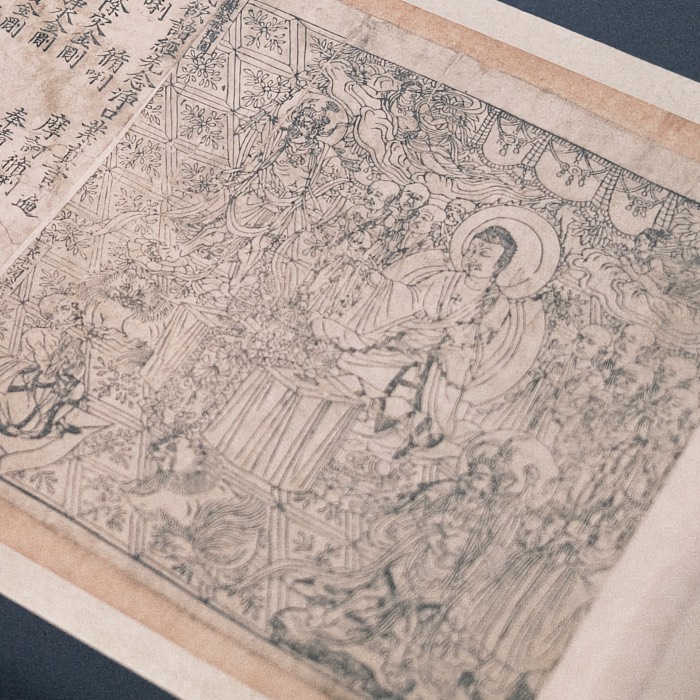

Characters of the Korean Phonetic Script, Ven. Mun Suan, Ink on paper, Korea, dated 1989. The monk Mun Suan of Tongdosa Temple wrote vowels, consonants and the beginning of the alphabet of the Korean phonetic script Hangeul ‘In the early spring of the year 4322 after Dangun’, i.e. 1989, as can be seen from the inscription. The strokes are written with an ink-rich brush. The shaky-looking lines are intended to be reminiscent of historical writings (Kor. goche). The signature and two of the five seals are also written in Hangeul, the former with lively calligraphy, the latter repeating the syllables ‘Su’ and ‘An’ in a graphically sober manner. The seals vary in the engraving technique: in one seal, they are cut (ground red, character white); in the other, they are carved in relief (ground white, character red).

Characters of the Korean Phonetic Script, Ven. Mun Suan, Ink on paper, Korea, dated 1989. The monk Mun Suan of Tongdosa Temple wrote vowels, consonants and the beginning of the alphabet of the Korean phonetic script Hangeul ‘In the early spring of the year 4322 after Dangun’, i.e. 1989, as can be seen from the inscription. The strokes are written with an ink-rich brush. The shaky-looking lines are intended to be reminiscent of historical writings (Kor. goche). The signature and two of the five seals are also written in Hangeul, the former with lively calligraphy, the latter repeating the syllables ‘Su’ and ‘An’ in a graphically sober manner. The seals vary in the engraving technique: in one seal, they are cut (ground red, character white); in the other, they are carved in relief (ground white, character red).

Today, hangeul is the dominant script in Korea, while hanja is used primarily for specific purposes such as academic texts or Chinese loanwords. Calligraphy in both scripts continues to be a respected art form, with contemporary artists exploring new styles and interpretations while maintaining a connection to traditional techniques (see, e.g., our previous post on the Chinese ink artist Jianfeng Pan)

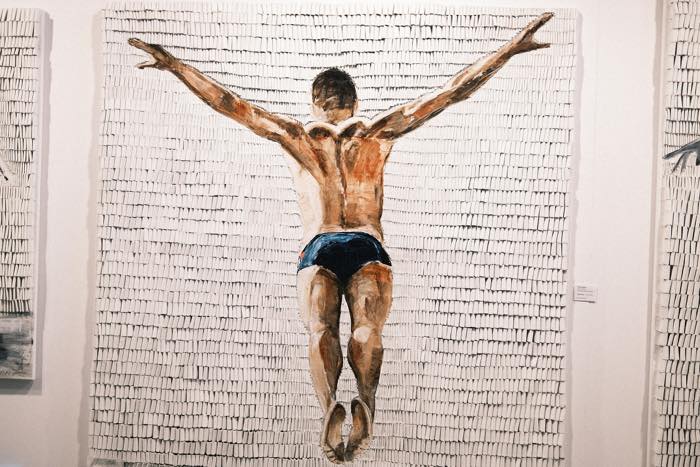

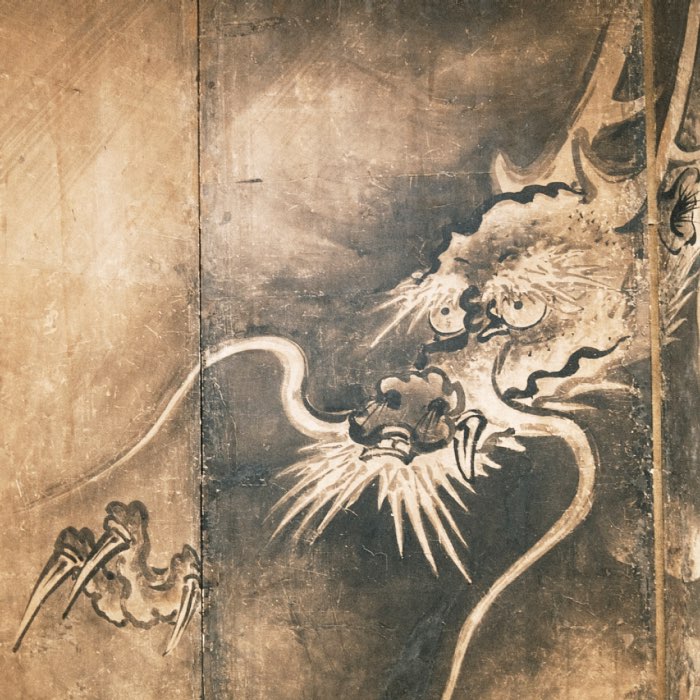

Calligraphy across artistic media

The exhibition emphasized that calligraphic brushwork in Korea is not confined to writing alone. Painting employs the same tools and closely related stroke techniques, with inscriptions often forming an integral part of the image. Beyond paper and silk, calligraphic aesthetics also permeate handcrafted objects. Ceramics and bronzes carry painted, impressed, or incised decorations whose visual logic is derived from the modulation, tension, and movement of the brush line.

By juxtaposing contemporary calligraphic works with traditional and modern paintings, as well as ceramics and bronzes from the Goryeo period (918–1392), the exhibition traced this continuity across time and material. The Goryeo era, often regarded as a cultural high point in Korean history, provided historical anchors for understanding how calligraphic principles shaped form well beyond the written page.

Old Man, Chang Woosoung (1912-2005), Ink and colours on paper Korea, 1981. As the pupil of the famous modern Korean painter Kim Eun-ho (1892-1978), Chang was renowned for his more traditional figure paint-ing. The painting ‘Old Man’ is executed in fine delicate pastels and Chang took special care in painting the outlines with sketch-like brushstrokes. The long flute playfully disrupts the vertical inscription, in which old age is contemplated.

Old Man, Chang Woosoung (1912-2005), Ink and colours on paper Korea, 1981. As the pupil of the famous modern Korean painter Kim Eun-ho (1892-1978), Chang was renowned for his more traditional figure paint-ing. The painting ‘Old Man’ is executed in fine delicate pastels and Chang took special care in painting the outlines with sketch-like brushstrokes. The long flute playfully disrupts the vertical inscription, in which old age is contemplated.

The One-Thousand-Year-Old Dragon-Pine of the Danho Temple, Yi Yeongbok (1955), Ink and colours on paper Korea, dated 2003. The inscription includes the name of the temple, the title of the painting and his studio-name ‘Pavilion of the whispering pine’ (kor. Cheongsonggan) in Chinese characters, while the date "mid-summer 2003" is written in Hangeul. Yi executes both with a fine brush in semi-cursive brush-strokes. The mighty pine consists of various texture-strokes applied on surfaces of ink washes. Yi used pointed strokes for the needles and ink-dots ranging from dark to light tones for the bark of the pine tree.

The One-Thousand-Year-Old Dragon-Pine of the Danho Temple, Yi Yeongbok (1955), Ink and colours on paper Korea, dated 2003. The inscription includes the name of the temple, the title of the painting and his studio-name ‘Pavilion of the whispering pine’ (kor. Cheongsonggan) in Chinese characters, while the date "mid-summer 2003" is written in Hangeul. Yi executes both with a fine brush in semi-cursive brush-strokes. The mighty pine consists of various texture-strokes applied on surfaces of ink washes. Yi used pointed strokes for the needles and ink-dots ranging from dark to light tones for the bark of the pine tree.

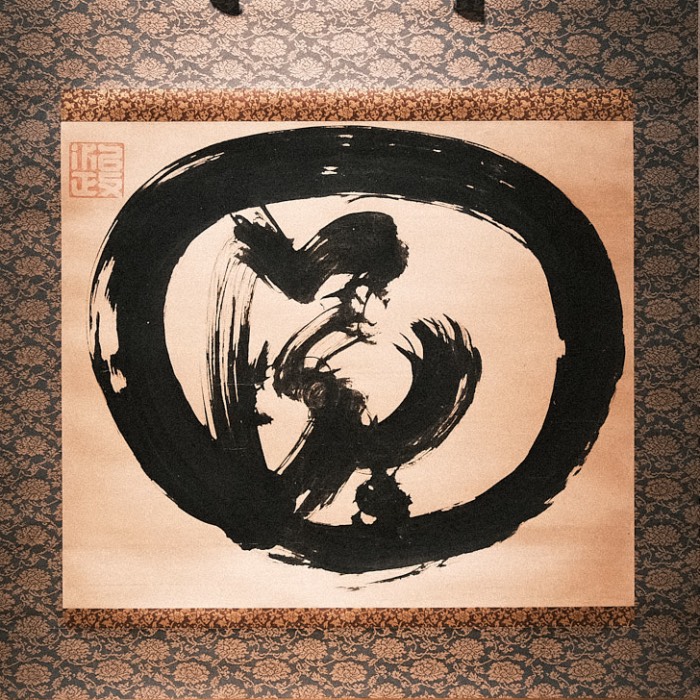

The River Rhine (Kor. 라인강, ra-in-kang), Jeon Myungok (b. 1954), Ink on paper, Korea, 2007. This calligraphic work was created during a performance celebrating the opening of the exhibition ‘Germany - Korea: The Smell of Indian Ink Preview’ on September 10th, 2007, in the Press and Information Office of the Federal Republic of Germany in Berlin. The three Hangeul syllables are boldly written with a thick brush on the surface of the paper, starting at the top left with ‘tra’, the first phonetic symbol of the river name. The brush is filled with ink, so that the strokes are thick and deeply black. The second syllable ‘Lin’ is smaller and placed in the upper right-hand corner. The syllable ‘okang’, and its last letter ‘Ong’ is written dynamically with a dry brush which barely touches the writing surface and imitates the swirling of water using the ‘Flying White’ (Kor. baekbi) technique. The seal at the bottom left is also written in Hangeul and states the name of the village Yubyeongri in Joellanam Province in Korea, probably the studio name of the artist.

The River Rhine (Kor. 라인강, ra-in-kang), Jeon Myungok (b. 1954), Ink on paper, Korea, 2007. This calligraphic work was created during a performance celebrating the opening of the exhibition ‘Germany - Korea: The Smell of Indian Ink Preview’ on September 10th, 2007, in the Press and Information Office of the Federal Republic of Germany in Berlin. The three Hangeul syllables are boldly written with a thick brush on the surface of the paper, starting at the top left with ‘tra’, the first phonetic symbol of the river name. The brush is filled with ink, so that the strokes are thick and deeply black. The second syllable ‘Lin’ is smaller and placed in the upper right-hand corner. The syllable ‘okang’, and its last letter ‘Ong’ is written dynamically with a dry brush which barely touches the writing surface and imitates the swirling of water using the ‘Flying White’ (Kor. baekbi) technique. The seal at the bottom left is also written in Hangeul and states the name of the village Yubyeongri in Joellanam Province in Korea, probably the studio name of the artist.

Additional highlights

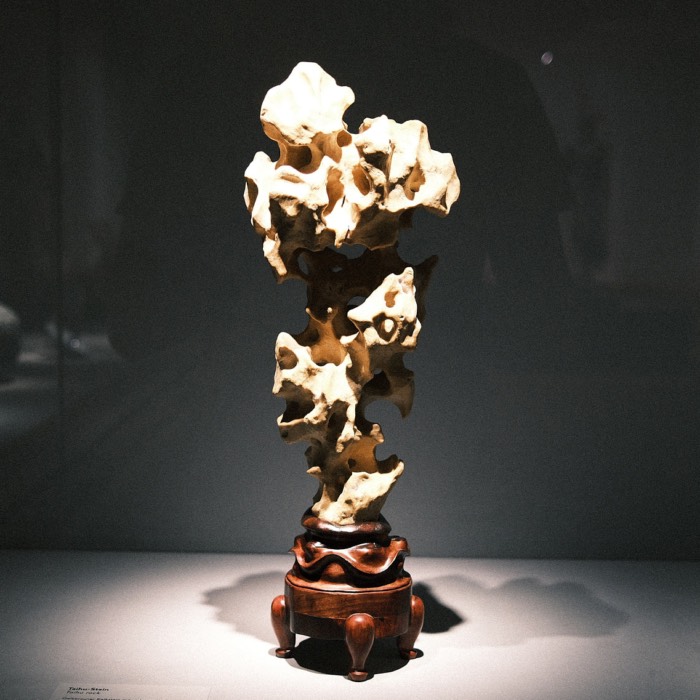

The exhibition room also featured several outstanding examples of Korean ceramics and bronzes from the Goryeo period, demonstrating the high level of craftsmanship and artistic expression of Korean artisans during this era.

Ewer in the Shape of a Gourd, Stoneware with engraved decor under celadon glaze Korea, Goryeo Period (918-1392), 12th cent. The ewer in the shape of a gourd is particularly balanced, the cord-shaped handle and the spout, which has been restored with gold lacquer, are elegantly curved. Also the application of the engraved lotus flower sprays with their detailed lines as well as the bluish-green celadon glaze are of high quality.

Ewer in the Shape of a Gourd, Stoneware with engraved decor under celadon glaze Korea, Goryeo Period (918-1392), 12th cent. The ewer in the shape of a gourd is particularly balanced, the cord-shaped handle and the spout, which has been restored with gold lacquer, are elegantly curved. Also the application of the engraved lotus flower sprays with their detailed lines as well as the bluish-green celadon glaze are of high quality.

Maebyeong Vase with Crane and Cloud Decor, Stoneware with engobe under celadon glaze, Korea, Goryeo Period (918-1392), 13th or 14th cent. The Maebyeong vase (plum-shaped vase) has a particularly slim, S-shaped profile. The decor of auspicious clouds and cranes is inlaid with white and black slip or engobe. The neck is embellished with a cloud-head pattern, the foot with a meander border.

Maebyeong Vase with Crane and Cloud Decor, Stoneware with engobe under celadon glaze, Korea, Goryeo Period (918-1392), 13th or 14th cent. The Maebyeong vase (plum-shaped vase) has a particularly slim, S-shaped profile. The decor of auspicious clouds and cranes is inlaid with white and black slip or engobe. The neck is embellished with a cloud-head pattern, the foot with a meander border.

Long-necked Bottle with Chrysanthemum Decor, Stoneware with engobe under a celadon glaze, Korea, Goryeo Period (918-1392), 13th cent. Vertical fields of superimposed white chrysanthemum flowers with black leaves decorate the pear-shaped body of the bottle. While a frieze of lotos leaves in-laid with white engobe emphasizes the foot of the bottle, black and white flame-like elements decorate the neck. Note, that the bottle seems to have been broken and had been repaired using the Japanese kintsugi technique, where the cracks are filled with gold lacquer.

Long-necked Bottle with Chrysanthemum Decor, Stoneware with engobe under a celadon glaze, Korea, Goryeo Period (918-1392), 13th cent. Vertical fields of superimposed white chrysanthemum flowers with black leaves decorate the pear-shaped body of the bottle. While a frieze of lotos leaves in-laid with white engobe emphasizes the foot of the bottle, black and white flame-like elements decorate the neck. Note, that the bottle seems to have been broken and had been repaired using the Japanese kintsugi technique, where the cracks are filled with gold lacquer.

Long necked Ewer, Stoneware with engobe under celadon glaze, Korea, Goryeo Period (918-1392), mid-12th cent. The shape of the ewer with its pear-shaped body, the C-shaped handle and the high, outwardly curved spout is reminiscent of Persian metalwork. The decoration shows ribbons and peony flowers in detailed and precise execution, whereby a rare inlay technique was used below the lip, in which not the motives but the background was cut and filled with engobe (Kor. yak-sanggam).

Long necked Ewer, Stoneware with engobe under celadon glaze, Korea, Goryeo Period (918-1392), mid-12th cent. The shape of the ewer with its pear-shaped body, the C-shaped handle and the high, outwardly curved spout is reminiscent of Persian metalwork. The decoration shows ribbons and peony flowers in detailed and precise execution, whereby a rare inlay technique was used below the lip, in which not the motives but the background was cut and filled with engobe (Kor. yak-sanggam).

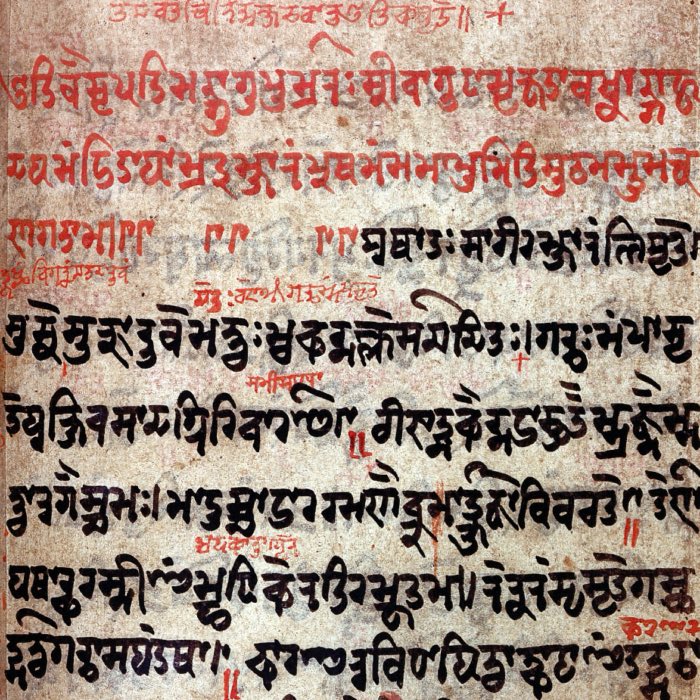

Buddhist Bell, Bronze, Korea, Joseon Period (1392-1910), 19th cent. The bell has an opposing dragon pair handle. Its body is decorated alternately with four Bodhisattva reliefs and four nine-fold humped flower-fields. Rings with a mantra in Sanskrit script surround the bodhisattvas’ halos. The decor as a whole is designed in simple shapes.

Buddhist Bell, Bronze, Korea, Joseon Period (1392-1910), 19th cent. The bell has an opposing dragon pair handle. Its body is decorated alternately with four Bodhisattva reliefs and four nine-fold humped flower-fields. Rings with a mantra in Sanskrit script surround the bodhisattvas’ halos. The decor as a whole is designed in simple shapes.

Also on display in one of the neighbouring areas: A Chinese altar set from the Qing dynasty, which allows a comparison of parallel artistic developments in China (well, in a broader temporal sense of course as both, the Ming dynasty lasted from 1368 to 1644, while the Goryeo and Joseon periods in Korea spanned from 918 to 1392 and from 1392 to 1910, respectively; so, it’s a large temporal window we are looking at here):

Five-piece altar set (wugong), enamels on copper, China, Qing dynasty, 19th century. Since the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), worshippers in Buddhist and Daoist temples have made offerings of scent, light and flowers to the gods. This is to ensure that their prayers are accepted. Incense is lit in the central vessel, flanked by a pair of candle-sticks and the flower vases on the outside. The vessel shapes were adopted from archaic ceremonial vessels, which were originally used for food and wine offerings to the ancestors, gods and spirits.

Five-piece altar set (wugong), enamels on copper, China, Qing dynasty, 19th century. Since the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), worshippers in Buddhist and Daoist temples have made offerings of scent, light and flowers to the gods. This is to ensure that their prayers are accepted. Incense is lit in the central vessel, flanked by a pair of candle-sticks and the flower vases on the outside. The vessel shapes were adopted from archaic ceremonial vessels, which were originally used for food and wine offerings to the ancestors, gods and spirits.

Conclusion

I think, The Line made visible how deeply calligraphy is embedded in Korean artistic traditions. Something, I wasn’t aware of before. Rather than treating writing, painting, and object design as separate domains, brushstroke seem to be interpreted as an interconnected visual language that transcends boundaries of the underlying medium. This holistic approach to brushwork and line quality seems to be a distinctive feature of Korean art, setting it apart from other East Asian traditions (while others, like Chinese and Japanese art, also share similar principles).

The exhibition is still running until autumn 2026. So, if you happen to be in Cologne, I can warmly recommend a visit.

References and further reading

- Website of the exhibitionꜛ

- Adele Schlombs, Sybille Girmond, Meisterwerke aus China, Korea und Japan, 1995, Prestel, ISBN: 9783791314945

- Soyoung Lee, Denise Patry Leidy, Silla - Korea’s Golden Kingdom, 2013, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, ISBN: 9780300197020

- Uta Werlich, Entdeckung Korea! - Schätze aus deutschen Museen, 2011, The Korea Foundation, ISBN: 9788986090413

- Heinz Götze, Chinesische und Japanische Kalligraphie aus zwei Jahrtausenden, 1987, Prestel, ISBN: 9783791307954

comments