Revisiting the Moore’s law of Neuroscience, 15 years later

I recently stumbled over a small but remarkably forward-looking paper from 2011 that I had not read before. Its central claim is that neuroscience has its own version of Moore’s law, at least when it comes to the number of neurons that can be recorded simultaneously.

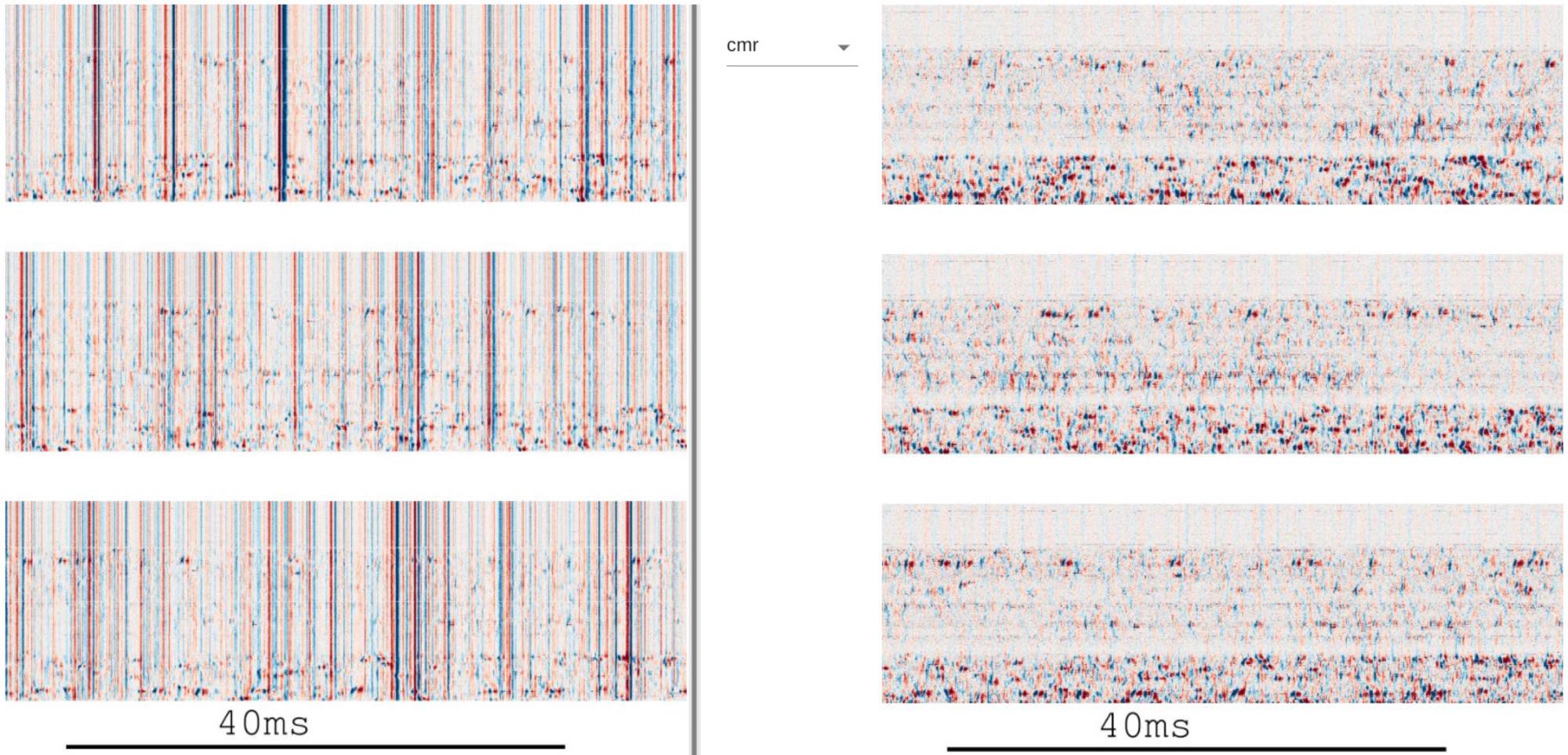

By today’s techniques such as Neuropixels probes, it is possible to record from thousands of neurons simultaneously.Figure 3 (panel a) from Alessio P. Buccino et al. (2025)ꜛ shows the output of the visualization and quality control stage in a modern large-scale spike sorting pipeline for such large data sets. The panel displays raw (left) and preprocessed (right) electrophysiological data recorded with Neuropixels 2.0 probes, highlighting the dense spatiotemporal structure of the recorded signals and the necessity of scalable preprocessing, inspection, and quality control before spike sorting and downstream analysis. The figure exemplifies the practical data volumes and organizational challenges that accompany contemporary high-density neural recordings. Stevenson and Kording predicted such developments over a decade ago by noting the exponential growth in simultaneously recorded neurons. Source: Figure 3 from Buccino et al., Efficient and reproducible pipelines for spike sorting large-scale electrophysiology data, 2025, bioRxiv 2025.11.12.687966, doi: 10.1101/2025.11.12.687966ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

By today’s techniques such as Neuropixels probes, it is possible to record from thousands of neurons simultaneously.Figure 3 (panel a) from Alessio P. Buccino et al. (2025)ꜛ shows the output of the visualization and quality control stage in a modern large-scale spike sorting pipeline for such large data sets. The panel displays raw (left) and preprocessed (right) electrophysiological data recorded with Neuropixels 2.0 probes, highlighting the dense spatiotemporal structure of the recorded signals and the necessity of scalable preprocessing, inspection, and quality control before spike sorting and downstream analysis. The figure exemplifies the practical data volumes and organizational challenges that accompany contemporary high-density neural recordings. Stevenson and Kording predicted such developments over a decade ago by noting the exponential growth in simultaneously recorded neurons. Source: Figure 3 from Buccino et al., Efficient and reproducible pipelines for spike sorting large-scale electrophysiology data, 2025, bioRxiv 2025.11.12.687966, doi: 10.1101/2025.11.12.687966ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

This observation was articulated by Ian H. Stevenson and Konrad Kording in their Nature Neuroscienceꜛ perspective How advances in neural recording affect data analysis. Based on a systematic survey of the electrophysiology literature, they argued that the number of simultaneously recorded neurons has been growing exponentially for decades, with a doubling time of roughly seven years.

At first glance, this sounds like a catchy analogy. But the paper makes a deeper point: If this scaling holds, it fundamentally reshapes what kinds of data analysis, models, and theories are viable in computational neuroscience.

The empirical “law”

Stevenson and Kording examined 56 studies spanning roughly five decades, starting with early single-electrode recordings in the 1950s and extending to then-modern multi-electrode arrays and optical techniques. When plotting the maximum number of simultaneously recorded neurons reported in each era, they found an approximately straight line on a logarithmic scale. The fitted doubling time was about 7.4 ± 0.4 years.

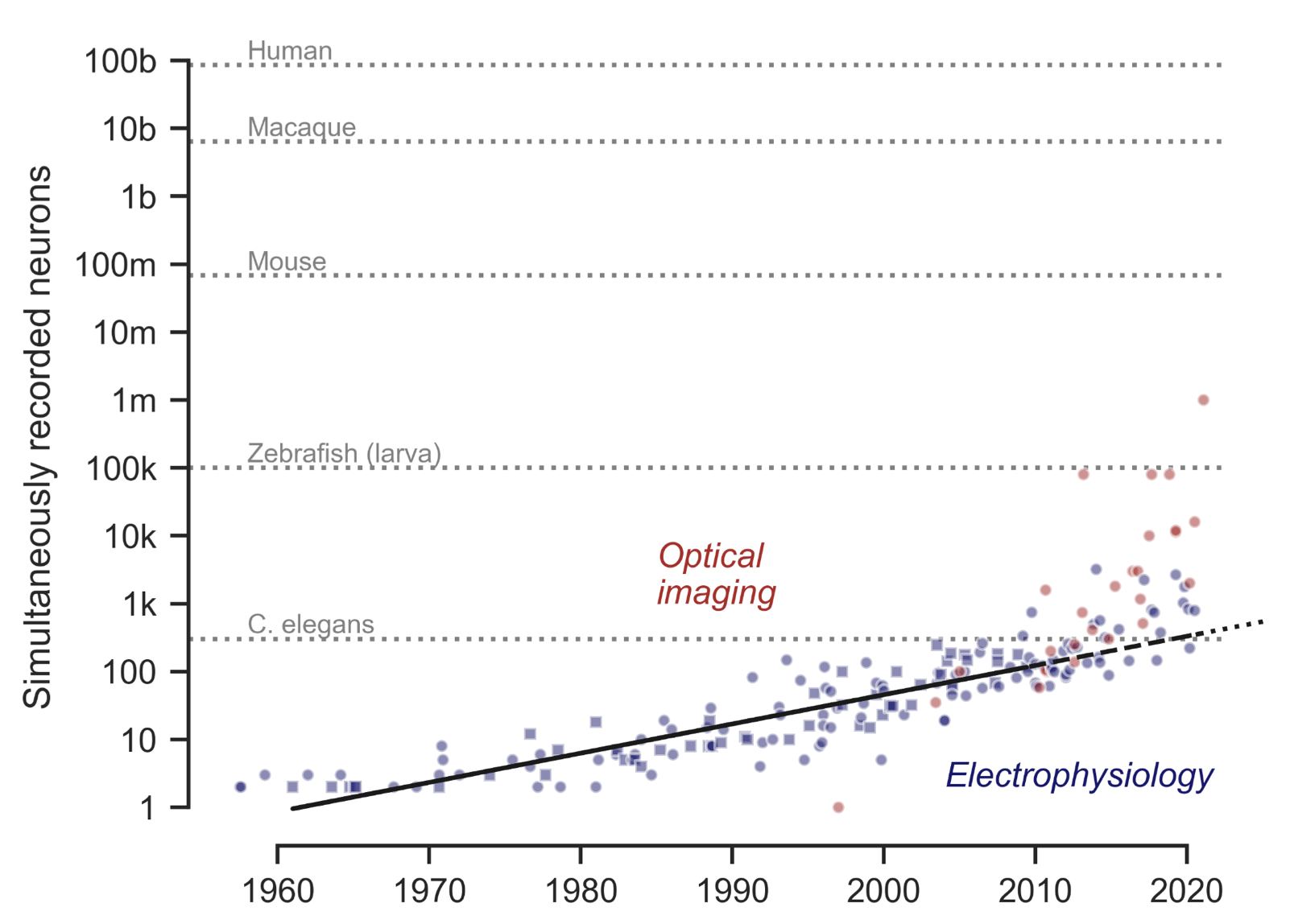

A more recent study by Anne E. Urai et al. (2021)ꜛ confirms and extends the pattern identified by Stevenson and Kording. Here is their Figure 2, summarizing the scaling of neural recording technologies across modalities and species from the 1950ies to the 2020ies. Blue points indicate the number of simultaneously recorded neurons using electrophysiological methods, including the original dataset analyzed by Stevenson & Kording (2011)ꜛ, shown as squares. Red points show population sizes achieved with optical imaging techniques such as two-photon and light-sheet microscopy. The solid line represents an exponential fit to the original electrophysiology data, while dashed and dotted black lines extrapolate this trend to the present and near future. Gray reference lines mark the approximate number of neurons in the brains of commonly studied model organisms. Not only are Stevenson and Kording’s observations upheld, but the trend also extends to optical methods, even further accelerating the growth in recorded neuron counts. Source: Anne E. Urai, Brent Doiron, Andrew M. Leifer, Anne K. Churchland, Large-scale neural recordings call for new insights to link brain and behavior, arXiv:2103.14662, doi:

10.48550/arXiv.2103.14662ꜛ, Figure available at github.com/anne-urai/largescale_recordingsꜛ (license: CC-BY)

A more recent study by Anne E. Urai et al. (2021)ꜛ confirms and extends the pattern identified by Stevenson and Kording. Here is their Figure 2, summarizing the scaling of neural recording technologies across modalities and species from the 1950ies to the 2020ies. Blue points indicate the number of simultaneously recorded neurons using electrophysiological methods, including the original dataset analyzed by Stevenson & Kording (2011)ꜛ, shown as squares. Red points show population sizes achieved with optical imaging techniques such as two-photon and light-sheet microscopy. The solid line represents an exponential fit to the original electrophysiology data, while dashed and dotted black lines extrapolate this trend to the present and near future. Gray reference lines mark the approximate number of neurons in the brains of commonly studied model organisms. Not only are Stevenson and Kording’s observations upheld, but the trend also extends to optical methods, even further accelerating the growth in recorded neuron counts. Source: Anne E. Urai, Brent Doiron, Andrew M. Leifer, Anne K. Churchland, Large-scale neural recordings call for new insights to link brain and behavior, arXiv:2103.14662, doi:

10.48550/arXiv.2103.14662ꜛ, Figure available at github.com/anne-urai/largescale_recordingsꜛ (license: CC-BY)

To be clear here: This is not presented as a law of nature. It is an empirical regularity, contingent on technological innovation. The authors explicitly compare it to Moore’s law not because it is guaranteed to persist forever, but because it is a useful abstraction for thinking about scaling. Just as Moore’s law shaped algorithm design in computer science, exponential growth in recording capacity should shape how we design neural data analysis methods.

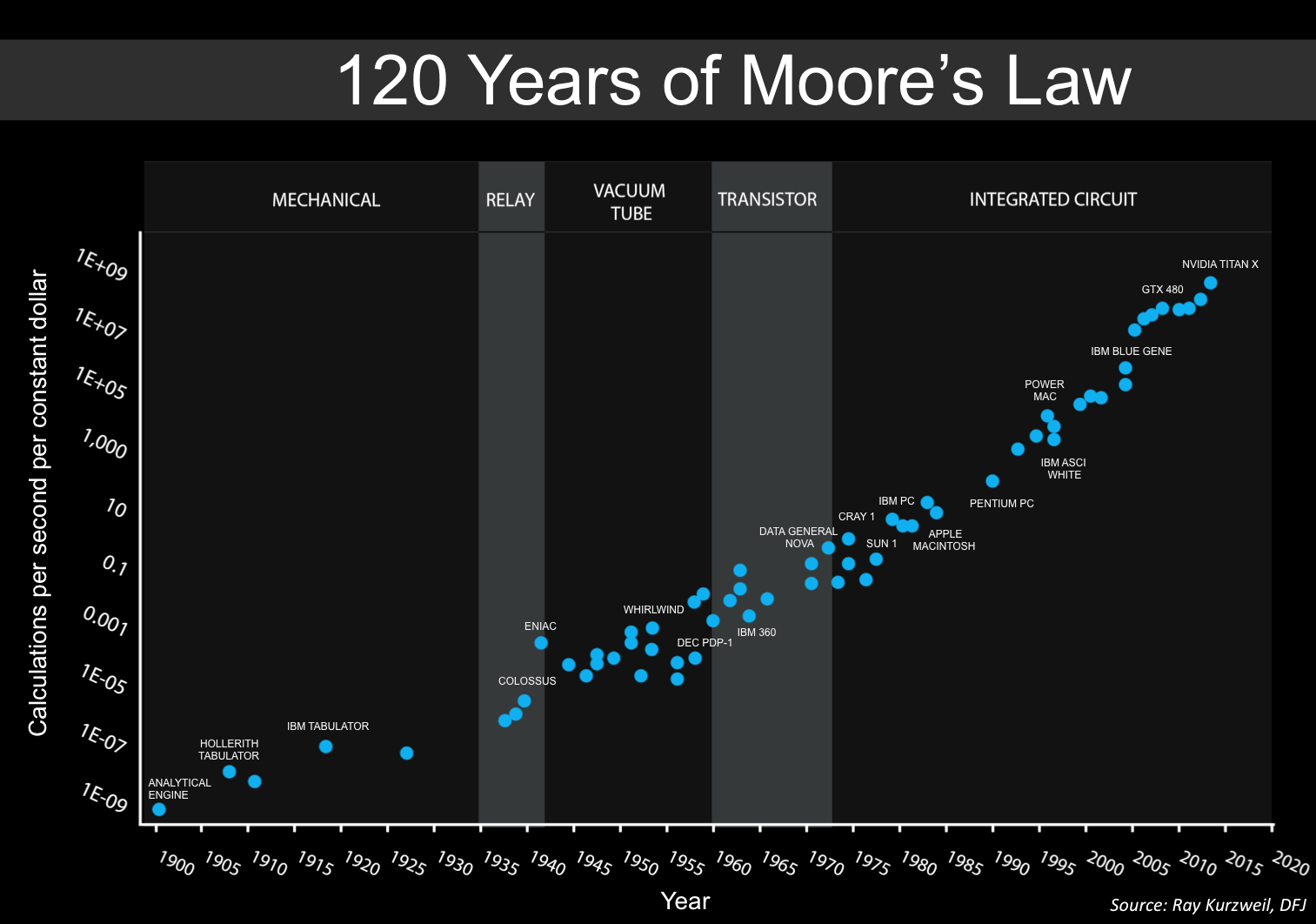

For comparison, Moore’s law states that the number of transistors on integrated circuits doubles approximately every two years. This empirical observation, made by Gordon Moore in 1965, has held remarkably well for several decades, driving exponential growth in computing power and efficiency. Source: Wikimedia Commons (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

For comparison, Moore’s law states that the number of transistors on integrated circuits doubles approximately every two years. This empirical observation, made by Gordon Moore in 1965, has held remarkably well for several decades, driving exponential growth in computing power and efficiency. Source: Wikimedia Commons (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

They also emphasize that the growth is driven by multiple, mutually reinforcing factors: Advances in electrode fabrication, automated silicon processing, wiring density, data acquisition hardware, storage, and transfer rates. Many of these improvements would have seemed implausible a few decades earlier.

A concrete prediction

One of the most memorable parts of the paper is its forward extrapolation. If the seven-year doubling trend continued, physiologists should be able to record from on the order of 1,000 neurons simultaneously within about 15 years. The authors explicitly state that this seemed feasible even in 2011, based on existing micro-wire arrays and the rapid development of two- and three-photon calcium imaging.

How Neuropixels probes enable large-scale neural recordings

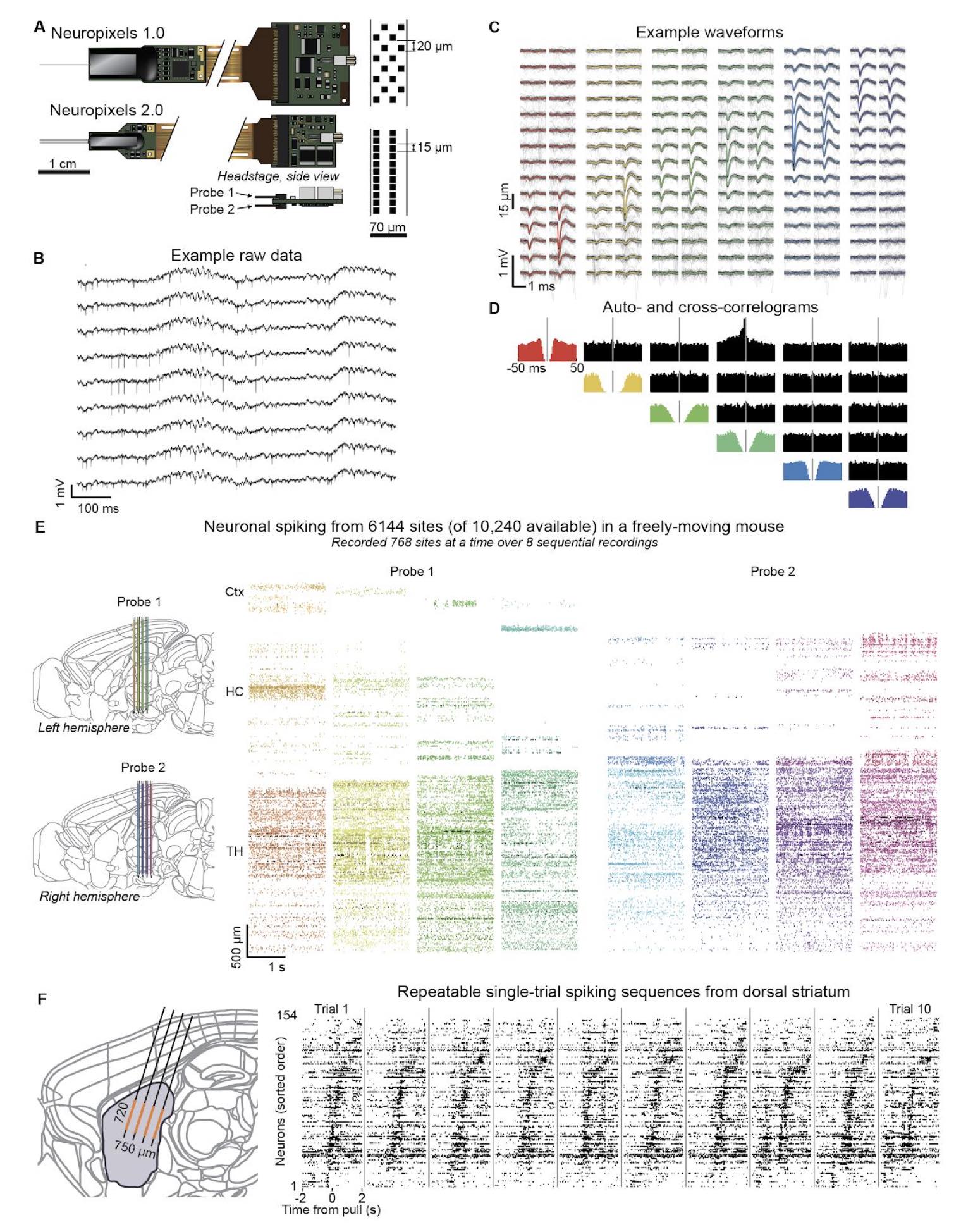

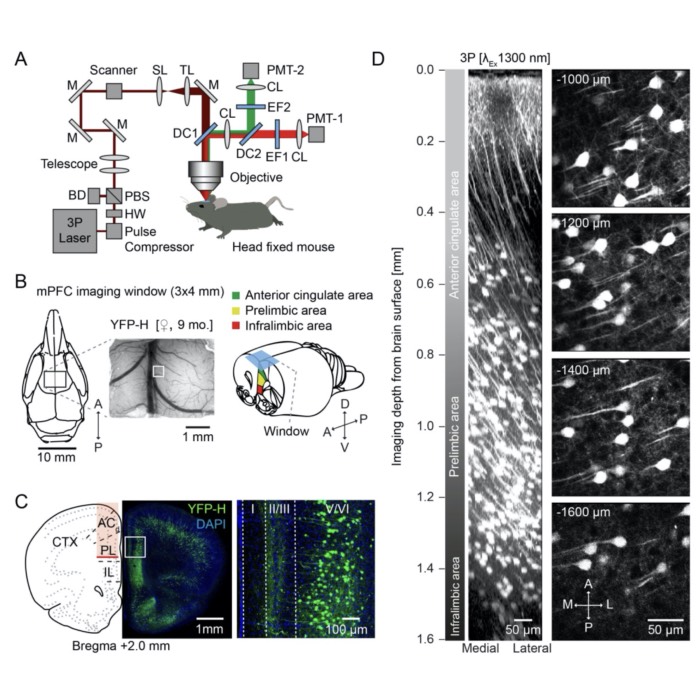

Neuropixels probes are high-density silicon electrode arrays designed to record extracellular activity from large neural populations with single-neuron resolution. The figure below from Steinmetz et al. (2020)ꜛ illustrates the key design principles and recording capabilities of Neuropixels 2.0.

Neuropixels 2.0 enables dense, large-scale extracellular recordings. Shown is Figure 1 from Steinmetz et al. (2020)ꜛ showing how Neuropixels probes support population-level recordings with single-neuron resolution. The figure illustrates the miniaturized high-density probe architecture, example raw extracellular signals and spike waveforms, validation using auto- and cross-correlograms, and large-scale spiking activity recorded across thousands of sites spanning multiple brain regions. Source: Figure 1 from Steinmetz et al., Neuropixels 2.0: A miniaturized high-density probe for stable, long-term brain recordings, 2020, bioRxiv 2020.10.27.358291, doi: 10.1101/2020.10.27.358291ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

Neuropixels 2.0 enables dense, large-scale extracellular recordings. Shown is Figure 1 from Steinmetz et al. (2020)ꜛ showing how Neuropixels probes support population-level recordings with single-neuron resolution. The figure illustrates the miniaturized high-density probe architecture, example raw extracellular signals and spike waveforms, validation using auto- and cross-correlograms, and large-scale spiking activity recorded across thousands of sites spanning multiple brain regions. Source: Figure 1 from Steinmetz et al., Neuropixels 2.0: A miniaturized high-density probe for stable, long-term brain recordings, 2020, bioRxiv 2020.10.27.358291, doi: 10.1101/2020.10.27.358291ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

Miniaturized, high-density probe design (panel A)

Neuropixels probes integrate thousands of recording sites onto one or multiple thin silicon shanks. The name “Neuropixels” reflects that each recording site acts as an individual spatial sampling element, analogous to a pixel in an image sensor, but measuring extracellular voltage instead of light intensity. Neuro-pixels are therefore not optical sensors such as miniature cameras, LEDs, or photodiodes, but dense arrays of microelectrodes for recording neural activity. Each site consists of a microscopic metal electrode connected to on-chip amplification, filtering, and multiplexing circuitry. Neuronal action potentials generate local extracellular voltage deflections that are detected simultaneously by multiple nearby sites, creating spatially distributed spike waveforms.

Neuropixels probes are inserted directly into the brain tissue along the shank axis (see panel E and F, schematics on the left), typically using micromanipulators that allow precise positioning across cortical and subcortical regions. Importantly, individual recording sites do not correspond one-to-one to individual neurons. Instead, each electrode samples the superposition of extracellular signals from multiple nearby neurons, with signal amplitude decaying with distance from the electrode. As a consequence, spikes from a single neuron are usually observed across several adjacent sites, while each site records contributions from multiple neurons. Post-processing algorithms exploit this spatial redundancy to isolate and identify individual neurons from the mixed signals.

Compared to Neuropixels 1.0, Neuropixels 2.0 increases site density while reducing the size and weight of the base and headstage, enabling chronic recordings in freely moving animals. Each probe contains several thousand electrodes distributed along the shank with micrometer spacing, allowing dense spatial sampling across cortical and subcortical structures. In post hoc analysis, this redundancy across channels is exploited to separate and localize individual neurons by clustering multi-channel spike waveforms, a process known as spike sorting.

Extracellular signal acquisition (panel B, C)

Shown are the raw local extracellular voltage traces recorded by each electrode site (panel B) along with example spike waveforms from individual neurons (panel C). The present fluctuations are caused by nearby neuronal activity. Low-frequency components reflect local field potentials, while high-frequency components correspond to action potentials. Because spikes from a single neuron are detected on multiple nearby channels, characteristic spatial waveform patterns emerge, as shown by example waveforms spanning overlapping sites.

Spike identity and timing validation (panel D)

Auto- and cross-correlograms are used to assess refractory periods and temporal relationships between units. The presence of a refractory period in autocorrelograms provides a biophysical constraint for identifying single neurons, while cross-correlograms reveal shared inputs or functional interactions between units.

Large-scale, multi-region recordings (panel E)

Neuropixels probes can record from hundreds of channels simultaneously and access thousands of sites sequentially via on-chip switching. In the example shown, activity from more than 6,000 recording sites was obtained using two probes implanted in a single mouse. This design enables dense sampling across extended depths of the brain, spanning multiple regions within one experiment.

Population-level dynamics on single trials (panel F)

Dense spatial coverage allows structured spiking patterns to be observed across large neuronal populations on individual trials. Reproducible spatiotemporal spike sequences, such as those observed in dorsal striatum during behavior, illustrate how Neuropixels recordings support population-level analyses that go beyond single-neuron tuning.

Neuropixels probes have become a central technology for large-scale electrophysiology. By dramatically increasing the number of simultaneously recorded neurons while maintaining signal quality and spatial resolution, they exemplify the technological scaling that motivates new analysis methods in modern computational neuroscience.

Currently, there is even an optogenetic version of Neuropixels probes under development (see Lakunia et al. (2025)ꜛ), which would further expand their capabilities by enabling simultaneous recording and manipulation of neural activity with high spatial precision.

They also stress the limits of such extrapolation. Tissue displacement, toxicity, bleaching, spike sorting, and spatial constraints all impose hard biological and practical boundaries. The famous thought experiment of recording from all ~100 billion neurons in the human brain is acknowledged as absurd when extrapolated linearly, yet the authors deliberately remind us how often similar extrapolations in computing once sounded absurd as well.

The important message is not the endpoint, but the regime change that happens long before any extreme limit is reached.

Why scaling changes the analysis

The second half of the paper turns from technology to computation. Stevenson and Kording ask a very specific question: How does spike prediction accuracy scale with the number of simultaneously recorded neurons, and how does this depend on the class of model being used?

They contrast two dominant approaches.

The first treats neurons independently. Classical tuning curve and receptive field models fall into this category. Each neuron’s firing rate is modeled as a function of external variables such as stimulus orientation or movement direction. Because neurons are fit independently, adding more neurons does not improve spike prediction accuracy for any single neuron. The accuracy remains essentially constant as population size grows.

The second class explicitly models interactions between neurons. Pairwise coupling models, implemented here as linear-nonlinear Poisson models with interaction terms, allow the activity of other recorded neurons to influence spike probability. In this case, prediction accuracy increases with the number of recorded neurons. In both motor and visual cortex datasets, the authors observed an approximately logarithmic scaling with population size.

This result has an important caveat that the paper makes very clear. The observed log N scaling occurs in highly undersampled recordings. In more complete recordings, where most relevant inputs are observed, prediction accuracy is expected to saturate. The scaling also depends on spatial scale, correlation strength, and how neurons are distributed across the tissue.

Still, the qualitative conclusion is robust: Interaction models benefit from larger populations in a way that independent models do not.

Latent state spaces as a way out

The paper also highlights a third approach that has since become central to population neuroscience: Low-dimensional latent variable or state-space models. Rather than modeling all pairwise interactions explicitly, these methods assume that population activity is driven by a small number of hidden factors. Dimensionality reduction and regularization are framed not as optional conveniences, but as necessities imposed by scaling and the curse of dimensionality.

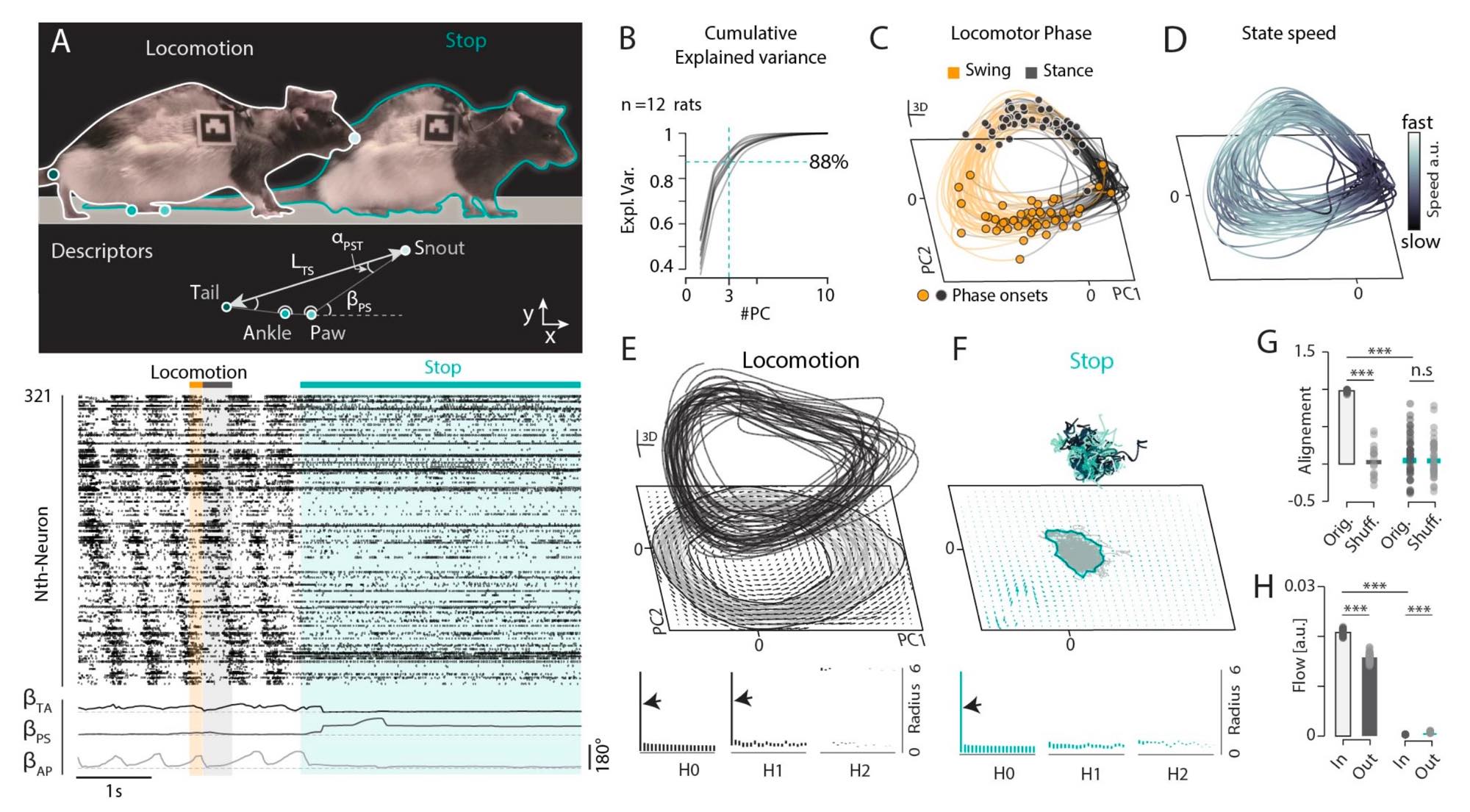

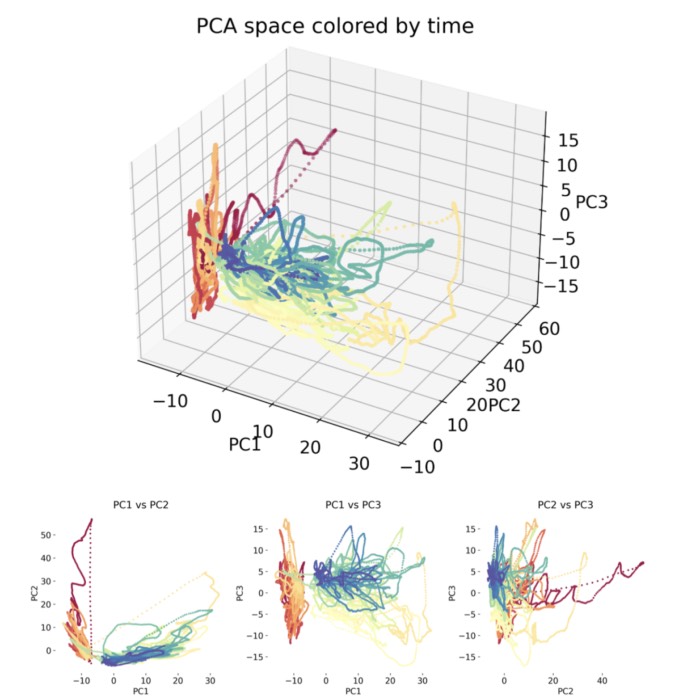

Figure 3 (panels A–H) from S. Komi et al. (2025)ꜛ demonstrates low-dimensional neural manifolds underlying locomotion and stopping. The figure illustrates how population activity in spinal motor circuits can be described by structured trajectories in a low-dimensional latent space. Panel A shows behavioral and neural data during walk-to-stop transitions, including pose metrics and phase-aligned spinal spike rasters. Panel B quantifies dimensionality reduction, showing that the first three principal components explain more than 80% of the variance in population firing rates, indicating strong low-dimensional structure. Panels C–E depict state-space trajectories during locomotion, forming a ring-shaped “locomotor manifold” with phase-dependent dynamics and a consistent flow direction, corresponding to a limit-cycle attractor. Persistent homology analysis confirms the ring topology. Panels F–H show that stopping behavior corresponds to a transition into a distinct postural manifold characterized by fixed-point attractor dynamics. Overall, this examples shows how large-scale neural recordings can be reduced to interpretable latent dynamics that link population activity to behavior. Such manifold-based interpretations of neural activity are a direct response to the challenges of scaling and have become a central framework in modern computational neuroscience. Source: Figure 3 from S. Komi, J. Kaur, A. Winther, M. C. Adamsson Bonfils, G. A. Houser, R. J. F. Sørensen, G. Li, K. Sobriel, R. W. Berg, Neural manifolds that orchestrate walking and stopping, 2025, Vol. n/a, Issue n/a, pages n/a, doi: 10.1101/2025.11.08.687367ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

Figure 3 (panels A–H) from S. Komi et al. (2025)ꜛ demonstrates low-dimensional neural manifolds underlying locomotion and stopping. The figure illustrates how population activity in spinal motor circuits can be described by structured trajectories in a low-dimensional latent space. Panel A shows behavioral and neural data during walk-to-stop transitions, including pose metrics and phase-aligned spinal spike rasters. Panel B quantifies dimensionality reduction, showing that the first three principal components explain more than 80% of the variance in population firing rates, indicating strong low-dimensional structure. Panels C–E depict state-space trajectories during locomotion, forming a ring-shaped “locomotor manifold” with phase-dependent dynamics and a consistent flow direction, corresponding to a limit-cycle attractor. Persistent homology analysis confirms the ring topology. Panels F–H show that stopping behavior corresponds to a transition into a distinct postural manifold characterized by fixed-point attractor dynamics. Overall, this examples shows how large-scale neural recordings can be reduced to interpretable latent dynamics that link population activity to behavior. Such manifold-based interpretations of neural activity are a direct response to the challenges of scaling and have become a central framework in modern computational neuroscience. Source: Figure 3 from S. Komi, J. Kaur, A. Winther, M. C. Adamsson Bonfils, G. A. Houser, R. J. F. Sørensen, G. Li, K. Sobriel, R. W. Berg, Neural manifolds that orchestrate walking and stopping, 2025, Vol. n/a, Issue n/a, pages n/a, doi: 10.1101/2025.11.08.687367ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

In retrospect, this section reads almost like a roadmap for the following decade. Gaussian process factor analysis, latent dynamical systems, population trajectories, and manifold-based interpretations of neural activity all fit squarely into the framework Stevenson and Kording sketched in 2011.

Fifteen years later

From today’s perspective, roughly fifteen years after publication, the core prediction has largely held. Simultaneous recordings of hundreds to thousands of neurons are now routine with Neuropixels probes and advanced optical imaging. Long-term, stable recordings across days or weeks are no longer exotic. What has not materialized in the same way is straightforward whole-brain spike recording, but that was never the real claim.

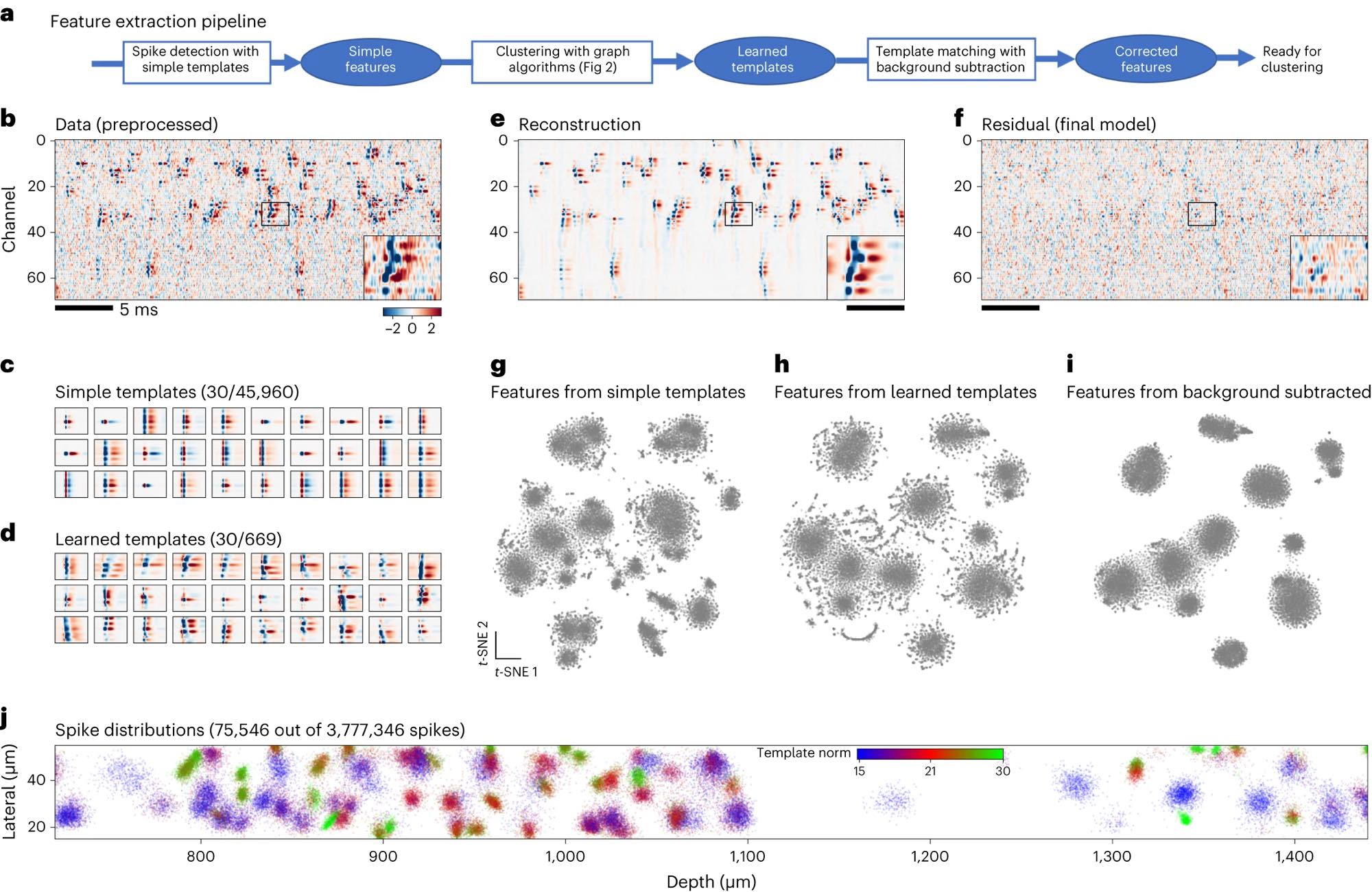

Figure 1 (panels a–j) from Marius Pachitariu et al. (2024)ꜛ illustrates the spike detection and feature extraction pipeline used in Kilosort4, exemplifying the analytical complexity introduced by large-scale neural recordings today. The figure shows how dense, high-channel-count recordings require multi-stage processing to separate overlapping spikes and extract meaningful features at scale. Panel a outlines the pipeline from initial spike detection using simple templates to refined, background-corrected features suitable for clustering. Panel b shows raw preprocessed Neuropixels data with frequent temporal and spatial spike overlap. Panels c and d compare predefined simple templates with learned templates adapted to the data. Panels e and f demonstrate signal reconstruction and residuals, highlighting structured activity beyond noise. Panels g–i visualize how feature representations improve with learned templates and background subtraction. Panel j shows the spatial distribution of extracted spikes along the probe. Together, the figure illustrates how advances in recording density necessitate increasingly sophisticated analysis methods. Source: Pachitariu et al., Spike sorting with Kilosort4, 2024, Nature Methods, 914–921, doi: 10.1038/s41592-024-02232-7ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

Figure 1 (panels a–j) from Marius Pachitariu et al. (2024)ꜛ illustrates the spike detection and feature extraction pipeline used in Kilosort4, exemplifying the analytical complexity introduced by large-scale neural recordings today. The figure shows how dense, high-channel-count recordings require multi-stage processing to separate overlapping spikes and extract meaningful features at scale. Panel a outlines the pipeline from initial spike detection using simple templates to refined, background-corrected features suitable for clustering. Panel b shows raw preprocessed Neuropixels data with frequent temporal and spatial spike overlap. Panels c and d compare predefined simple templates with learned templates adapted to the data. Panels e and f demonstrate signal reconstruction and residuals, highlighting structured activity beyond noise. Panels g–i visualize how feature representations improve with learned templates and background subtraction. Panel j shows the spatial distribution of extracted spikes along the probe. Together, the figure illustrates how advances in recording density necessitate increasingly sophisticated analysis methods. Source: Pachitariu et al., Spike sorting with Kilosort4, 2024, Nature Methods, 914–921, doi: 10.1038/s41592-024-02232-7ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

More importantly, the computational consequences the authors anticipated have fully arrived. Interaction models, latent-variable approaches, and population-level dynamical analyses now dominate much of systems and computational neuroscience. At the same time, the challenges they emphasized, computational cost, statistical identifiability, and scaling behavior, remain central and unresolved in many contexts.

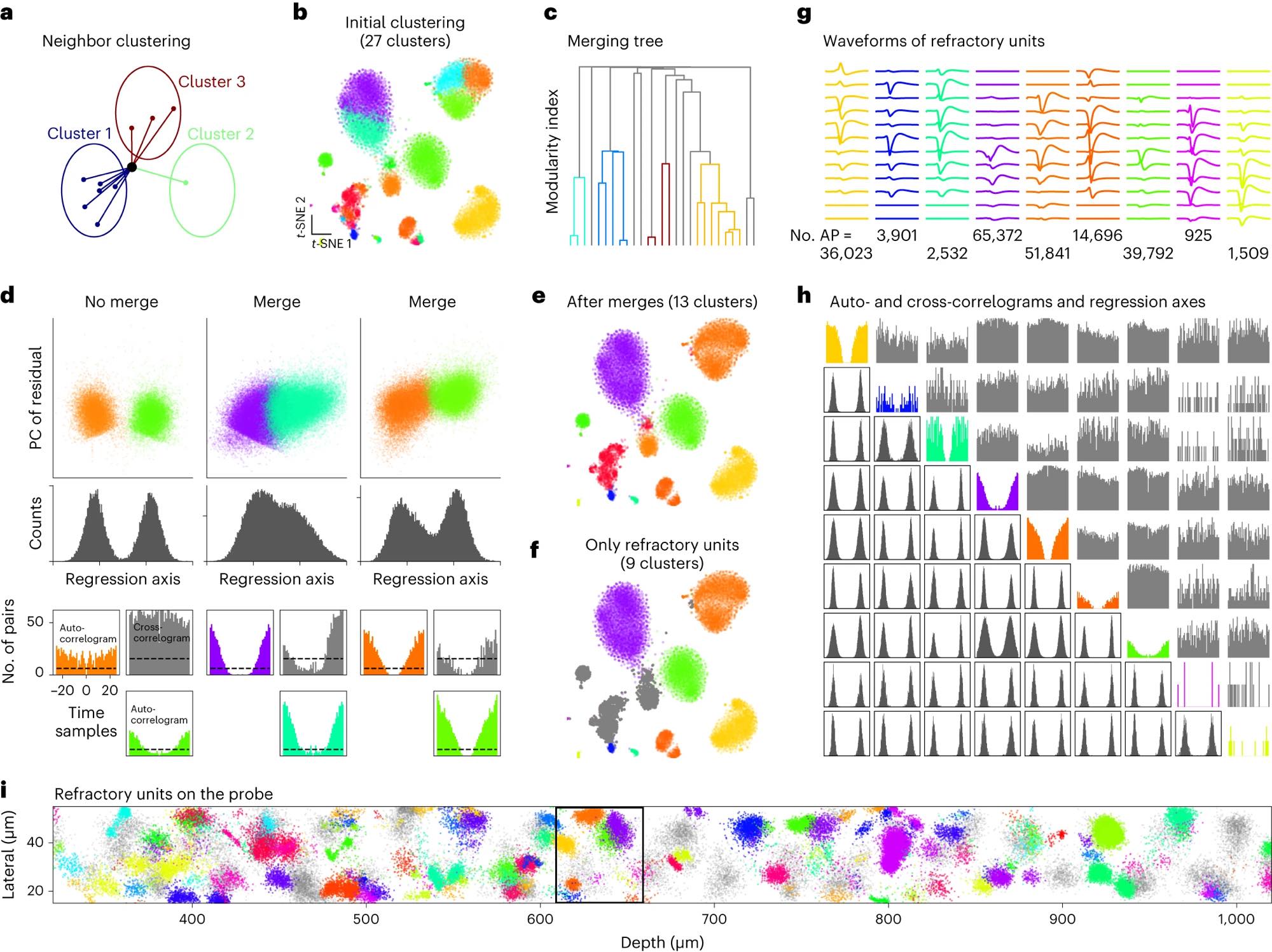

Figure 2 (panels a–i) from Marius Pachitariu et al. (2024) shows graph-based clustering strategies used in Kilosort4 to structure large-scale spike datasets. The figure illustrates how dense, high-dimensional spike features are iteratively reassigned and merged to obtain stable clusters from large neural populations. Panel a sketches the neighbor-based reassignment process that progressively reduces an initially large set of clusters. Panel b shows an example clustering overlaid on a t-SNE embedding of spike features. Panel c presents the hierarchical merging tree used to decide which clusters should be combined based on a modularity cost. Panel d summarizes the criteria for accepting or rejecting merges, combining feature-space bimodality with refractory-period constraints derived from spike timing. Panels e and f show the final clustering result, highlighting units that exhibit refractory periods. Panels g and h characterize the resulting units using average waveforms, autocorrelograms, cross-correlograms, and regression projections. Panel i visualizes the spatial distribution of clustered spikes along the probe. Together, the figure exemplifies how modern spike sorting algorithms impose structure on massive datasets by combining graph methods, statistical criteria, and biophysical constraints. Source: Pachitariu et al., Spike sorting with Kilosort4, 2024, Nature Methods, 914–921, doi: 10.1038/s41592-024-02232-7ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

Figure 2 (panels a–i) from Marius Pachitariu et al. (2024) shows graph-based clustering strategies used in Kilosort4 to structure large-scale spike datasets. The figure illustrates how dense, high-dimensional spike features are iteratively reassigned and merged to obtain stable clusters from large neural populations. Panel a sketches the neighbor-based reassignment process that progressively reduces an initially large set of clusters. Panel b shows an example clustering overlaid on a t-SNE embedding of spike features. Panel c presents the hierarchical merging tree used to decide which clusters should be combined based on a modularity cost. Panel d summarizes the criteria for accepting or rejecting merges, combining feature-space bimodality with refractory-period constraints derived from spike timing. Panels e and f show the final clustering result, highlighting units that exhibit refractory periods. Panels g and h characterize the resulting units using average waveforms, autocorrelograms, cross-correlograms, and regression projections. Panel i visualizes the spatial distribution of clustered spikes along the probe. Together, the figure exemplifies how modern spike sorting algorithms impose structure on massive datasets by combining graph methods, statistical criteria, and biophysical constraints. Source: Pachitariu et al., Spike sorting with Kilosort4, 2024, Nature Methods, 914–921, doi: 10.1038/s41592-024-02232-7ꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

A personal takeaway

What strikes me most reading this paper today is not how bold it was, but how measured. Stevenson and Kording were not selling a technological fantasy. They were issuing a methodological warning. Data will keep growing. Models that ignore scaling will quietly fail. Models that exploit structure, regularization, and low-dimensionality stand a chance.

If neuroscience really does have its own Moore’s law, then the obligation for computational neuroscience is clear. We cannot afford to treat population size as a secondary detail. It is a defining constraint that shapes which theories are even expressible, let alone testable.

References and further reading

- Ian H Stevenson, Konrad P Kording, How advances in neural recording affect data analysis, 2011, Nature Neuroscience, Vol. 14, Issue 2, pages 139-142, doi: 10.1038/nn.2731 ꜛ

- Buccino et al., Efficient and reproducible pipelines for spike sorting large-scale electrophysiology data, 2025, bioRxiv 2025.11.12.687966, doi: 10.1101/2025.11.12.687966ꜛ

- Anne E. Urai, Brent Doiron, Andrew M. Leifer, Anne K. Churchland, Large-scale neural recordings call for new insights to link brain and behavior, arXiv:2103.14662, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2103.14662ꜛ

- Marius Pachitariu, Shashwat Sridhar, Jacob Pennington, Carsen Stringer, Spike sorting with Kilosort4, 2024, Nature Methods, Vol. 21, Issue 5, pages 914-921, doi: 10.1038/s41592-024-02232-7ꜛ

- Marblestone AH, Zamft BM, Maguire YG, Shapiro MG, Cybulski TR, Glaser JI, Amodei D, Stranges PB, Kalhor R, Dalrymple DA, Seo D, Alon E, Maharbiz MM, Carmena JM, Rabaey JM, Boyden ES, Church GM and Kording KP, Physical principles for scalable neural recording, 2013, Front. Comput. Neurosci. 7:137. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2013.00137ꜛ

- Nicholas A. Steinmetz, Cagatay Aydin, Anna Lebedeva, Michael Okun, Marius Pachitariu, Marius Bauza, Maxime Beau, Jai Bhagat, Claudia Böhm, Martijn Broux, Susu Chen, Jennifer Colonell, Richard J. Gardner, Bill Karsh, Dimitar Kostadinov, Carolina Mora-Lopez, Junchol Park, Jan Putzeys, Britton Sauerbrei, Rik J. J. van Daal, Abraham Z. Vollan, Marleen Welkenhuysen, Zhiwen Ye, Joshua Dudman, Barundeb Dutta, Adam W. Hantman, Kenneth D. Harris, Albert K. Lee, Edvard I. Moser, John O’Keefe, Alfonso Renart, Karel Svoboda, Michael Häusser, Sebastian Haesler, Matteo Carandini, Timothy D. Harris, Neuropixels 2.0: A miniaturized high-density probe for stable, long-term brain recordings, 2020, bioRxiv 2020.10.27.358291, doi: 10.1101/2020.10.27.358291ꜛ / published in Science372, eabf4588(2021),doi: 10.1126/science.abf4588ꜛ

- Anna Lakunina, Karolina Z Socha, Alexander Ladd, Anna J Bowen, Susu Chen, Jennifer Colonell, Anjal Doshi, Bill Karsh, Michael Krumin, Pavel Kulik, Anna Li, Pieter Neutens, John O’Callaghan, Meghan Olsen, Jan Putzeys, Charu Bai Reddy, Harrie AC Tilmans, Sara Vargas, Marleen Welkenhuysen, Zhiwen Ye, Michael Häusser, Christof Koch, Jonathan T. Ting, Neuropixels Opto Consortium, Barundeb Dutta, Timothy D Harris, Nicholas A Steinmetz, Karel Svoboda, Joshua H Siegle, Matteo Carandini, Neuropixels Opto: Combining high-resolution electrophysiology and optogenetics, 2025, bioRxiv 2025.02.04.636286, doi: 10.1101/2025.02.04.636286ꜛ

- S. Komi, J. Kaur, A. Winther, M. C. Adamsson Bonfils, G. A. Houser, R. J. F. Sørensen, G. Li, K. Sobriel, R. W. Berg, Neural manifolds that orchestrate walking and stopping, 2025, Vol. n/a, Issue n/a, pages n/a, doi: 10.1101/2025.11.08.687367ꜛ

comments