Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 7/52

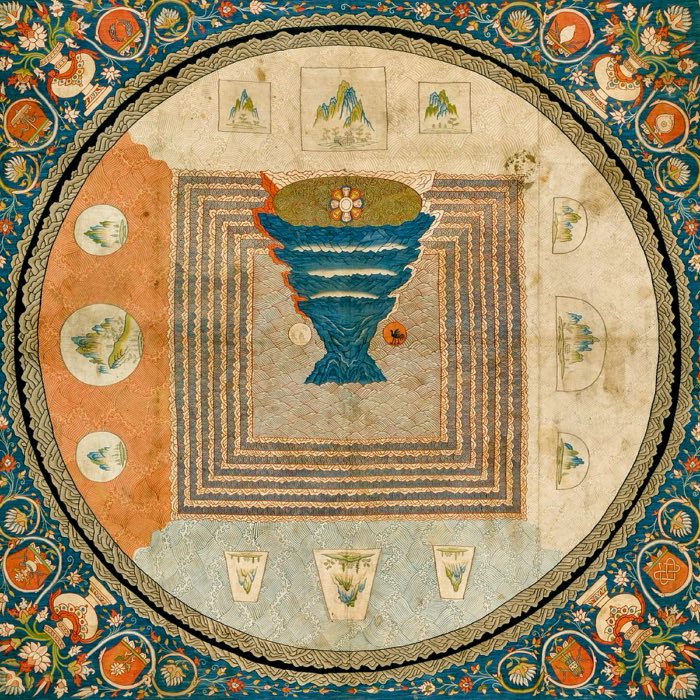

Buddhist cosmology: Mount Meru and the Ocean of Milk

Buddhist cosmology presents a vision of the universe that is at once highly structured, mythically rich, and deeply symbolic. Central to this vision are two powerful images inherited and reformulated from the broader South Asian religious milieu: Mount Meru, the cosmic axis around which the universe revolves, and the vast encircling Ocean of Milk. These elements are not merely ornamental myths but form a foundational part of traditional Buddhist worldviews, appearing in canonical texts, commentarial literature, visual art, and ritual practice. In this post, we explore how these motifs function across Buddhist traditions, not simply as relics of pre-scientific thought, but as enduring symbolic tools that continue to shape spiritual imagination, moral reflection, and cultural continuity.

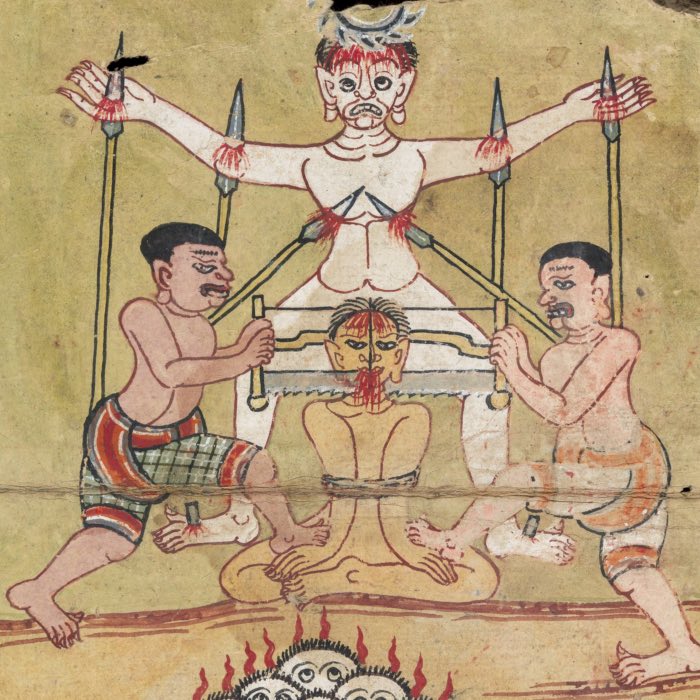

Buddhist hells

Among the many symbolic constructs in Buddhist cosmology, the depiction of hells (naraka) stands out for its vivid imagery and moral intensity. Often characterized by scenes of torment, fire, ice, and punishment, these realms challenge modern readers to ask: are these descriptions to be taken literally, or do they function symbolically? Are Buddhist hells metaphysical places, psychological states, or narrative devices to encourage ethical behavior? In this post, we approach the Buddhist hells not as dogmatic assertions of an afterlife realm, but as complex representations embedded in a broader framework of karmic causality, ethical reflection, and soteriological concern. In doing so, we situate the hells within the tradition’s layered hermeneutics: as real in their karmic consequences, impermanent in duration, and symbolic in function. Rather than being governed by divine wrath, these realms are shaped entirely by the moral quality of past actions. They are, in a sense, ethical landscapes produced by karma itself. Understanding the Buddhist hells requires attention to the interplay between myth, ethics, and practice. Far from being static depictions of punishment, the hells illustrate the consequences of harmful actions and the urgency of transformation. They serve as moral warnings, meditative reflections, and, in some schools, as spaces into which bodhisattvas willingly descend to offer aid. This multilayered role makes the Buddhist hells not only doctrinally significant but also spiritually and psychologically resonant across historical and cultural contexts.

Buddhist mythology: Symbol, function, and soteriological utility

Buddhist mythology weaves together rich narratives, symbols, and cosmological visions that transcend mere storytelling. While often misunderstood as superstition or cultural residue, these myths serve profound purposes: conveying ethical values, illustrating metaphysical truths, and guiding practitioners on the path to awakening. In this post, we explore the multifaceted role of mythology in Buddhism, examining its pedagogical, cosmological, and soteriological functions, as well as its relevance in modern contexts.

Dharmapālas: Guardians of the Buddhist path

Dharmapālas, or ‘Guardians of the Dharma’, are among the most striking figures in Buddhist tradition. With their fierce and wrathful appearances, they embody the paradox of compassionate protection through intensity. These protectors serve a dual purpose: safeguarding the teachings of the Buddha from external and internal threats while symbolizing the inner strength and clarity required to overcome obstacles on the path to awakening. In this post, we explore their origins, roles, and relevance across Buddhist traditions.

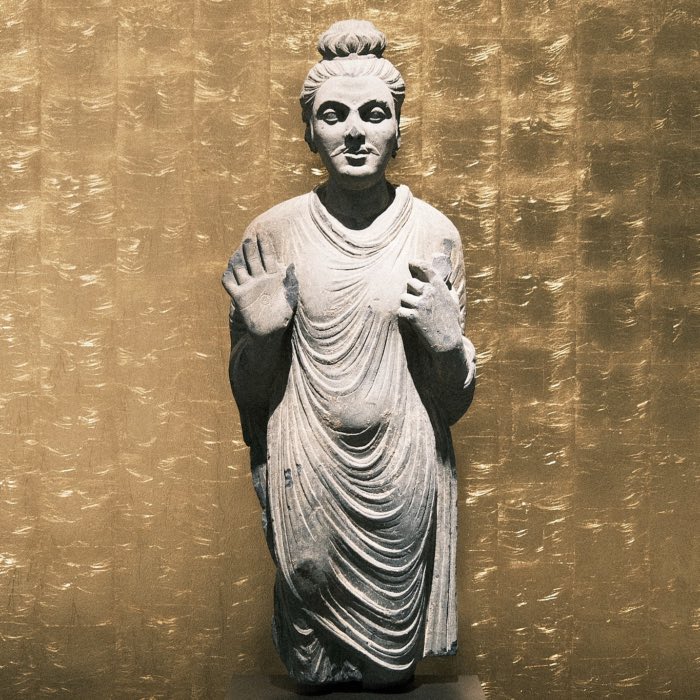

What is a Buddha?

What kind of being is a Buddha? This question opens the door to some of the most important distinctions in Buddhist thought: between human and divine, teacher and savior, historical individual and timeless archetype. The term “Buddha” appears across almost every branch of the tradition, and yet it is often left undefined or reduced to devotional shorthand. A Buddha is neither a god nor a prophet, but a human being who has fully awakened to the nature of reality and lives from that clarity. This post explores how the idea of Buddhahood has been understood, from early texts to Mahāyāna philosophy, from historical depictions to symbolic and contemporary reinterpretations. Over time, the Buddha came to be seen not only as a singular figure of the past but also as a model of human potential, perceived as the capacity to awaken, to act with wisdom, and to guide others toward liberation.

Bodhicitta: The heart of awakening

Bodhicitta, often translated as ‘awakening mind’ or ‘mind of enlightenment’, is the foundational intention and commitment that defines the bodhisattva path in Mahāyāna Buddhism. More than a thought or emotion, bodhicitta is a profound shift in orientation: the wish to attain full awakening not for oneself alone, but for the liberation of all sentient beings. In this post, we explore the meaning, development, and significance of bodhicitta, both in traditional Buddhist frameworks and in contemporary ethical practice.

The Bodhisattva: Mahāyāna ideal of compassion

What does it mean to be free? In early Buddhism, liberation is portrayed as the final release from saṃsāra, a cessation of craving, ignorance, and rebirth. But Mahāyāna Buddhism reimagines this freedom in a radically relational way. Here, awakening is not the end of the path, but its beginning: the bodhisattva, one who is fully awakened, chooses to remain within the world of suffering out of boundless compassion. In this post, we explore the bodhisattva ideal as both an ethical orientation and a philosophical revolution: A vision of enlightenment that turns inward insight into outward action, and personal freedom into universal care.

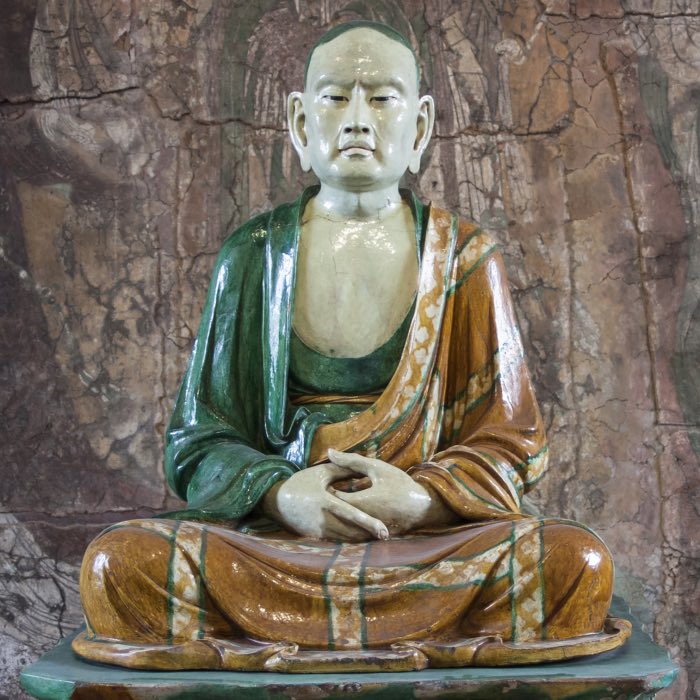

The Arhat: The ideal of liberation in early Buddhism

In the early Buddhist tradition, the figure of the Arhat (Pāli: Arahant) stands as the ideal of complete liberation. The term literally means ‘worthy’ or ‘one who is deserving of offerings’, but more profoundly, it signifies the person who has eliminated all defilements (kilesa) and reached the cessation of suffering — nirvana. Unlike later Mahāyāna conceptions of spiritual attainment, which often idealize the bodhisattva who forgoes nirvana to aid all beings, the Arhat is one who has completed the path. In this post, we explore the Arhat not only as a doctrinal figure, but also as a psychological, ethical, and mythological symbol within the broader fabric of Buddhist thought.

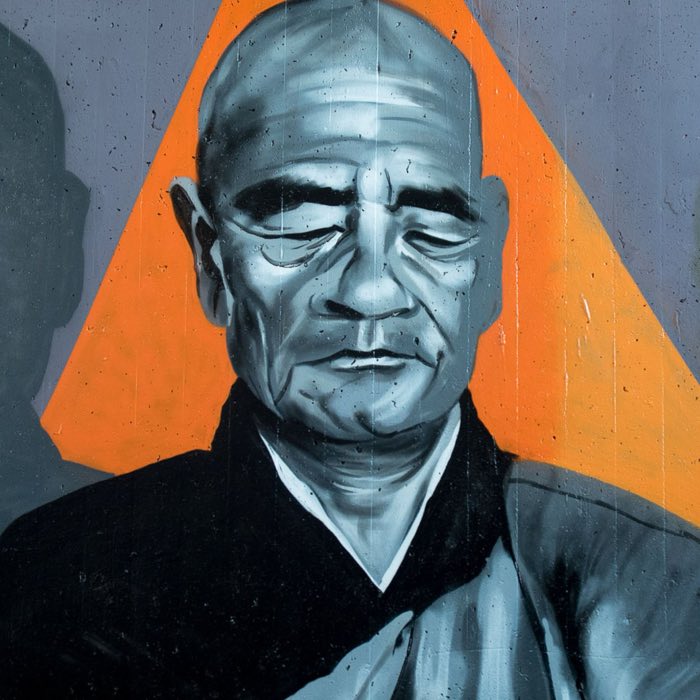

Taisen Deshimaru and the transmission of Zen to Europe

Taisen Deshimaru (1914–1982) played a crucial role in the transmission of Zen Buddhism from Japan to Europe in the twentieth century. Building on the foundations laid by figures like D.T. Suzuki and Shunryu Suzuki in America, Deshimaru offered an experiential, practice-centered form of Zen that took root among Western audiences, particularly in France. His work helped establish a living Zen tradition outside of Asia, not through philosophical exposition alone, but by cultivating actual dojos, practicing communities, and a monastic presence.

Shunryu Suzuki: Establishing Zen Practice in America

Shunryu Suzuki, a humble yet transformative figure in the history of Zen Buddhism, played a pivotal role in bringing authentic Zen practice to the United States. Arriving in San Francisco in 1959, Suzuki encountered a generation of seekers eager for spiritual depth and simplicity. Through his gentle guidance, he emphasized the essence of Zen: sitting meditation (zazen), mindfulness, and the cultivation of ‘beginner’s mind’. In this post, we explore Suzuki’s life, teachings, and enduring influence, highlighting how his quiet yet profound approach helped establish Zen as a living tradition in the West.