The Bonnefanten Museum: Curating sacred and secular art in a modern architectural space

On the same day I visited the Basilica of St. Servatius, I spent several hours at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht. Experiencing both places in close succession made it clear to me that sacred and secular spaces are not opposites, but different ways of structuring attention, meaning, and presence. In this post, I’d therefore like to reflect on that visit as well and explore on how architecture, display, and framing may shape perception across religious and modern cultural institutions.

Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, Netherlands.

Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, Netherlands.

Introduction

Moving from the basilica to the Bonnefanten is not just a change of building, but a change of cultural grammar. One space is shaped by ritual continuity and theological authority, the other by curatorial decision and institutional framing. Yet both rely on architecture, staging, and controlled attention to produce meaning.

View into the round ceiling at the entrance hall of the museum.

View into the round ceiling at the entrance hall of the museum.

What interests me here is not the contrast itself, but the overlap. The Bonnefanten places medieval Christian art — altarpieces, devotional objects, Flemish paintings — within the same institutional space as modern installations, conceptual works, and global contemporary positions. Objects that were once embedded in religious ritual are now isolated, labeled, and displayed. By the way, a similar approach that we have already discussed for the Museum Schnütgen in Cologne. At the same time, many modern and contemporary works reject figuration altogether and instead work with silence, reduction, affect, or spatial presence in ways that feel structurally familiar from religious contexts.

Grayson Perry, The Walthamstow Tapestry, 2009. Exhibited in the main entrance hall.

Grayson Perry, The Walthamstow Tapestry, 2009. Exhibited in the main entrance hall.

The transition from sacred to secular is therefore neither linear nor complete. What changes is not simply the content, but the frame. Meaning is no longer guaranteed by doctrine or ritual, but produced through display, proximity, and controlled perception. Rather than resolving this tension, the museum holds it in place. Sacred objects are not reactivated as devotional tools, but neither are they neutralized. Contemporary works are not framed as spiritual substitutes, yet they often demand a comparable mode of attention. The result is a space in which different historical regimes of meaning coexist, not reconciled, but carefully staged.

Wooden sculpture of Mary and Child along with a female figure (possibly St. Barbara (?) or an angel (?)).

Wooden sculpture of Mary and Child along with a female figure (possibly St. Barbara (?) or an angel (?)).

The museum as a modern architectural statement

The Bonnefanten Museum occupies a prominent site along the eastern bank of the river Meuse. Designed by Italian architect Aldo Rossi and opened in 1995, the building has become one of the most recognizable examples of postmodern architecture in the Netherlands. Its form is geometrically restrained yet symbolically charged: A mix of classical references, industrial cues, and urban monumentality. Most striking is the cylindrical tower with its metallic dome, which echoes the form of a lighthouse or observatory more than that of a traditional museum annex. It neither imitates nor denies historical architecture, but instead sets its own vocabulary, discrete from the surrounding city (but not indifferent to it).

Facing the river, the building presents itself as a distinct object. The façade, the materials, and the deliberate clarity of the volumes give the impression of a place set apart, though not in a religious sense. Unlike the Basilica of St. Servatius, which is embedded in the layered street grid of medieval Maastricht, the Bonnefanten stands slightly aloof, framed by the waterfront and the sky. In my view, the architecture communicates intention: This is a space where art is not embedded in liturgical time but isolated for viewing. The building does not offer access to a metaphysical domain, but it does stage a kind of detachment, a place where concentration, distance, and curated presence take precedence over function or doctrine.

View out of one of the museum’s large windows, overlooking the river Meuse. On the left and right, parts of the museum building are visible.

View out of one of the museum’s large windows, overlooking the river Meuse. On the left and right, parts of the museum building are visible.

This framing already shapes the visitor’s expectation before entering I think. The entrance sequence, the compressed transitional spaces, and the strict geometric clarity of the galleries define the museum as a secular structure of meaning. It adopts certain visual strategies from religious architecture such as symmetry, height, spatial rhythm, but retools them for a different purpose. Rather than housing the sacred, it houses the significant. The building declares: What happens inside may not be about salvation, but it is still important and of eternal and public interest.

A model ship exhibited in the main entrance hall.

A model ship exhibited in the main entrance hall.

Collections and curatorial strategy

The Bonnefanten Museum houses a broad collection that spans several centuries and aesthetic frameworks, from late medieval Christian art to postwar minimalism and contemporary installation. This range is not presented as a seamless historical narrative, nor is it divided into isolated departments. Instead, the curatorial strategy appears to embrace tension and juxtaposition: Sacred and secular, historical and conceptual, devotional and analytical.

View into one of the workshops, where exhbitions exponents are being restored, preserved, or prepared.

View into one of the workshops, where exhbitions exponents are being restored, preserved, or prepared.

Old Masters

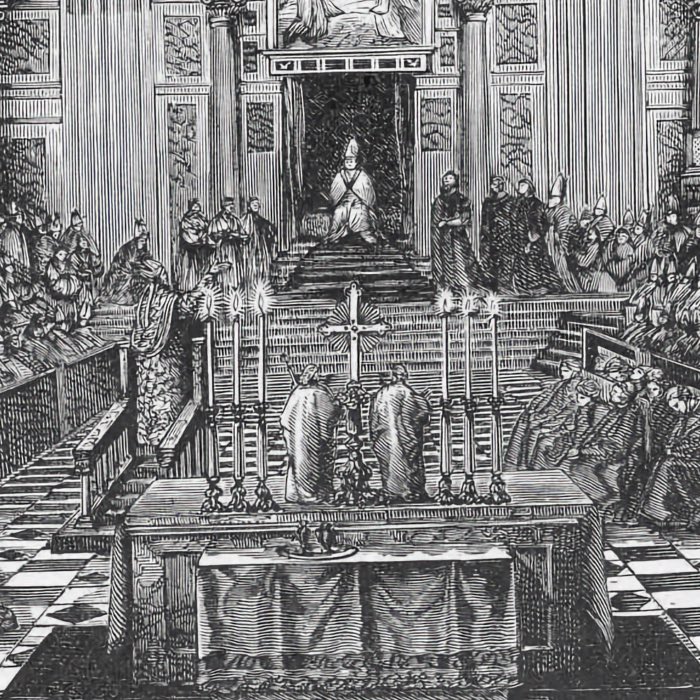

The collection of Old Masters includes notable works from the Southern Netherlands and Italy, many of them explicitly religious in content: Saints, madonnas, crucifixions, and altarpieces. These objects were originally produced for chapels, churches, and private devotion. Their iconography, materials, and compositional conventions reflect the same visual language that continues, albeit in transformed form, in the living heritage of the Basilica of St. Servatius. The museum setting, however, abstracts them from liturgical use and reframes them as objects of aesthetic and historical interest. They are isolated, labeled, and illuminated not for prayer, but for inspection. The shift is subtle but decisive: from veneration to evaluation.

Selected works from the Old Masters collection

Bonnefanten Museum’s Old Masters collection.

Bonnefanten Museum’s Old Masters collection.

Paul Bril, Landscape with Rest on the Flight into Egypt, ca. 1615.

Paul Bril, Landscape with Rest on the Flight into Egypt, ca. 1615.

Lucas Gassel, Flight into Egypt, 1542.

Lucas Gassel, Flight into Egypt, 1542.

Denijs van Alsloot, Landscape with Castle of Tervuren and Hunting Scene, 1608.

Denijs van Alsloot, Landscape with Castle of Tervuren and Hunting Scene, 1608.

Pieter Brueghel de Jonge (werkplaats), Census at Bethlehem, ca. 1605 - 1610.

Pieter Brueghel de Jonge (werkplaats), Census at Bethlehem, ca. 1605 - 1610.

One of the wide and light-flooded hallways.

One of the wide and light-flooded hallways.

Ambrosius Francken de Oude, Christ blessing the Children, ca. 1600.

Ambrosius Francken de Oude, Christ blessing the Children, ca. 1600.

Dirk de Quade van Ravesteijn, Allegory of Fertility, 1593.

Dirk de Quade van Ravesteijn, Allegory of Fertility, 1593.

Anoniem naar Godfried Maes, Acoetes finds Bacchus on the Island Chios, ca. 1762.

Anoniem naar Godfried Maes, Acoetes finds Bacchus on the Island Chios, ca. 1762.

Hieronymus van der Elst, The Shooting of the King’s Corpse, 1593.

Hieronymus van der Elst, The Shooting of the King’s Corpse, 1593.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (werkplaats), Madonna and Child, ca. 1490.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (werkplaats), Madonna and Child, ca. 1490.

Vicino da Ferrara werkzaam, Head of John the Baptist, ca. 1465 - 1469.

Vicino da Ferrara werkzaam, Head of John the Baptist, ca. 1465 - 1469.

Girolamo da Santacroce, St. John the Baptist, ca. 1540.

Girolamo da Santacroce, St. John the Baptist, ca. 1540.

Meester van de Madonna van Barmhartigheid, werkzaam, St. Miniatus, 1360 - 1365 (center) and Pietro Nelli, St. Catharine of Alexandria, ca. 1365 (right).

Meester van de Madonna van Barmhartigheid, werkzaam, St. Miniatus, 1360 - 1365 (center) and Pietro Nelli, St. Catharine of Alexandria, ca. 1365 (right).

Left: Meester van de Strauss Madonna, Madonna and Child, 1385 - 1390. Right: Meester van de CappellaMedici polyptiek, werkzoom, Holy Bishop, 1320 - 1330.

Left: Meester van de Strauss Madonna, Madonna and Child, 1385 - 1390. Right: Meester van de CappellaMedici polyptiek, werkzoom, Holy Bishop, 1320 - 1330.

Panel showing the birth of Christ. Unfortunately I forgot to note the artist and date.

Panel showing the birth of Christ. Unfortunately I forgot to note the artist and date.

Lorenzo Monaco (werkplaats), Virgin and Child Enthroned, 1415 - 1420.

Lorenzo Monaco (werkplaats), Virgin and Child Enthroned, 1415 - 1420.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (werkplaats), Man of Sorrows, ca. 1475.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (werkplaats), Man of Sorrows, ca. 1475.

Pieter Aertsen, The Last Judgement, ca. 1560

Pieter Aertsen, The Last Judgement, ca. 1560

Francesco di Girolamo da Santacroce (?), Banquet, ca. 1545.

Francesco di Girolamo da Santacroce (?), Banquet, ca. 1545.

Mercy Seat, ca. 1545, oil on canvas.

Mercy Seat, ca. 1545, oil on canvas.

Marco Marziale, Christ and The Adulteress, ca. 1506.

Marco Marziale, Christ and The Adulteress, ca. 1506.

Lamentation of Christ, ca. 1490, oil on panel.

Lamentation of Christ, ca. 1490, oil on panel.

Jan Van Brussel, Dual Justice, ca. 1475 - 1477 (datering van restauratie 1599), oil on panel.

Jan Van Brussel, Dual Justice, ca. 1475 - 1477 (datering van restauratie 1599), oil on panel.

Pieter de Kempeneer, The Deposition, 1550, oil on panel

Pieter de Kempeneer, The Deposition, 1550, oil on panel

Modern and contemporary art

In the same building, just on a different floor, the museum presents works of modern and contemporary art that follow a very different logic. These include minimal sculptures, conceptual installations, abstract painting, video pieces, and spatial interventions. Many of them reject figuration altogether; others engage with existential themes without reference to religious tradition. Some works are quiet and reductionist, emphasizing material presence or spatial emptiness. Others are provocative or enigmatic, designed to unsettle habitual responses. What they share is an orientation toward perception, attention, and reflection, qualities that overlap, at times surprisingly, with the atmosphere cultivated in religious spaces.

Folkert de Jong, The Shooting at Watou, 2006

Folkert de Jong, The Shooting at Watou, 2006

Folkert de Jong, The Shooting at Watou, 2006

Folkert de Jong, The Shooting at Watou, 2006

Folkert de Jong, The Shooting at Watou, 2006

Folkert de Jong, The Shooting at Watou, 2006

Folkert de Jong, The Shooting at Watou, 2006

Folkert de Jong, The Shooting at Watou, 2006

Folkert de Jong, The Shooting at Watou, 2006

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, 2025

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Carl Cheng, Nature Never Loses, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, 2025

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Mounira Al Solh, A land as big as her skin, Bonnefanten Museum 2025.

Curating contrast

I think, the curatorial approach does not attempt to reconcile these domains. It acknowledges their differences while placing them in visual and spatial proximity. This allows for resonances to emerge organically: A 15th-century sculpture of the Virgin on one floor, a minimalist steel form on the other. The visitor is not told how to interpret this sequence, but the museum implicitly asks whether these forms of image-making and spatial arrangement might be understood as responses to similar questions about presence, absence, meaning, and silence. In this way, the Bonnefanten becomes more than a container of artworks. It becomes a site of curated contrast, where religious heritage and artistic modernity confront each other without resolution.

Laure Provost, Cooling System 10 for Global Warming, 2019.

Laure Provost, Cooling System 10 for Global Warming, 2019.

Domenico di Michelino, The Expulsion from Paradise, 1450 - 1475.

Domenico di Michelino, The Expulsion from Paradise, 1450 - 1475.

Gerhard Seghers, Christ and the Penitent Sinners, ca. 1640 - 1651.

Gerhard Seghers, Christ and the Penitent Sinners, ca. 1640 - 1651.

Benoit Hermans, Flesh Back, 2005

Benoit Hermans, Flesh Back, 2005

Lucas Cranach de Jonge (werkplaats), Christus en de overspelige vrouw, 1549 - 1549 (detail).

Lucas Cranach de Jonge (werkplaats), Christus en de overspelige vrouw, 1549 - 1549 (detail).

Helen Verhoeven, Church I, 2017 - 2018

Helen Verhoeven, Church I, 2017 - 2018

Experiencing art across temporal boundaries

Navigating the Bonnefanten Museum involves a vertical movement through distinct cultural and temporal registers. The upper floors are devoted to modern and contemporary art: Installations, conceptual works, video pieces, while the lower floors contain the museum’s historical collections, including late medieval devotional art and works by the Old Masters. The separation is spatially clear, but the conceptual transition it demands remains unresolved. One descends or ascends not just between floors, but between radically different systems of meaning.

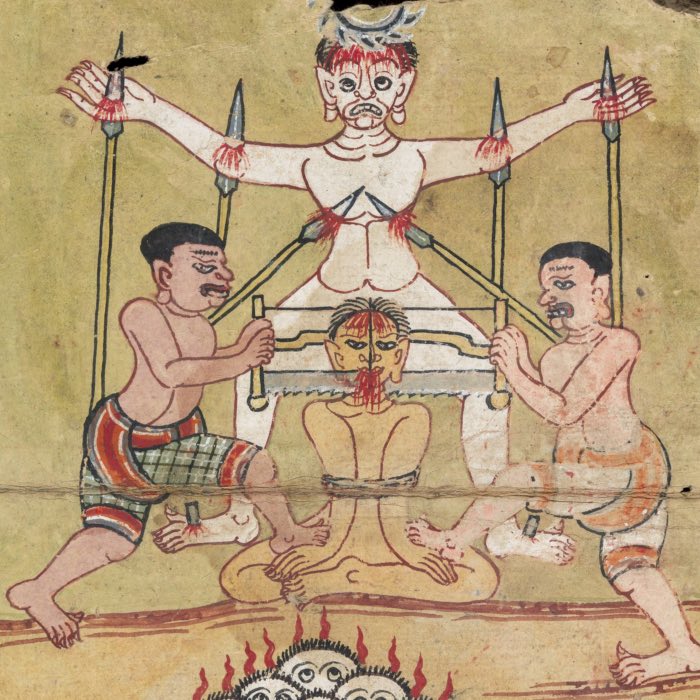

The older objects were created for religious contexts. Their original function depended on their integration into liturgical or devotional practice: altarpieces in chapels, votive statues in shrines, processional crosses on feast days. In the museum, these objects are no longer embedded in use but reframed for visual analysis. They are presented behind glass, illuminated by spotlights, and supplemented with explanatory labels. This curatorial context shifts the viewer’s role from participant to observer, from devotion to inspection.

Upstairs, the modern and contemporary works follow a different aesthetic but share certain staging strategies. Minimal lighting, sparse wall texts, controlled acoustics, and large open spaces define the experience. These works often reject narrative or representation, yet they still depend on spatial isolation, formal focus, and extended attention. They may not invite belief, but they clearly request presence.

Despite their chronological and conceptual distance, both groups of objects rely on similar environmental conditions to shape how they are perceived. In both cases, meaning arises not simply from the object itself, but from the frame in which it is encountered. The museum’s architecture and curatorial logic structure perception in ways that recall religious spaces: thresholds, silence, and spatial clarity play a role in producing resonance.

This continuity complicates any strict separation between sacred and secular experience. It suggests that modern art institutions have adopted, consciously or not, some of the perceptual mechanisms that once defined religious environments. The viewer is not told what to believe, but is asked to look, to pause, to reflect. That shared structure of attention makes the Bonnefanten more than a repository of unrelated objects. It becomes a place where different temporalities and cultural frameworks can be read in relation, not through content, but through how they condition the act of looking.

Selected religious artworks

Jan van Steffeswert, Seated Bishop, ca. 1515

Jan van Steffeswert, Seated Bishop, ca. 1515

Jakobus de Meerdere, Saint James the Great, ca. 1500

Jakobus de Meerdere, Saint James the Great, ca. 1500

Stained Glass with Depiction of Saints Servatius and Leonard and a Canon, 16th century.

Stained Glass with Depiction of Saints Servatius and Leonard and a Canon, 16th century.

Wooden statue of a female figure. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

Wooden statue of a female figure. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

Ensemble of a crucifix and two wooden statues. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

Ensemble of a crucifix and two wooden statues. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

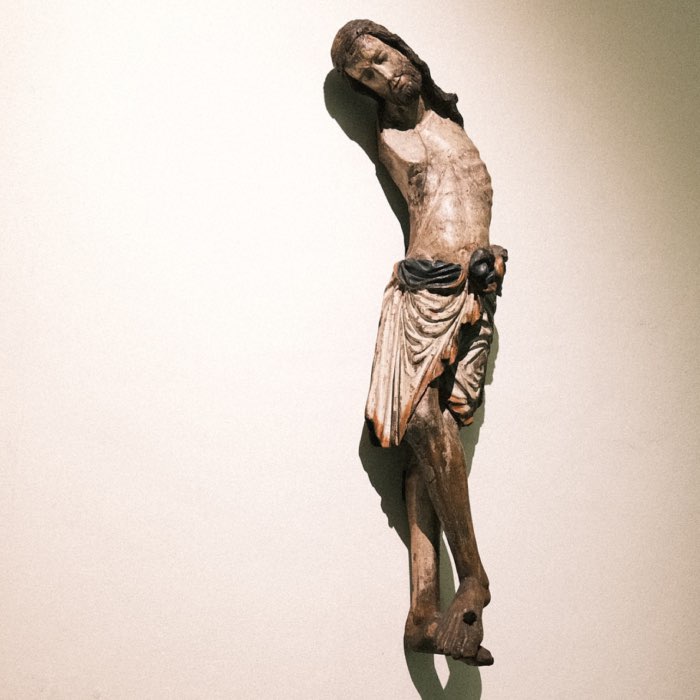

Cruzifix. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

Cruzifix. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

St. Hubert, ca. 1520 (Maaslandgebied).

St. Hubert, ca. 1520 (Maaslandgebied).

Left: Hendrick Douverman (navolger), Saint Augustine, ca. 1520 - 1530. Right: Jan van Steffeswert, Holy Bishop (St. Augustine?), ca. 1520.

Left: Hendrick Douverman (navolger), Saint Augustine, ca. 1520 - 1530. Right: Jan van Steffeswert, Holy Bishop (St. Augustine?), ca. 1520.

John the Evangelist from a Calvary Group, ca. 1320.

John the Evangelist from a Calvary Group, ca. 1320.

Ensemble of wooden statues, depciting most likely saints. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

Ensemble of wooden statues, depciting most likely saints. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

Wooden altarpiece depicting the Virgin and Child with Saints. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

Wooden altarpiece depicting the Virgin and Child with Saints. Unfortunately, I don’t have more details about this artwork.

Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1525 - 1540, lime wood

Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1525 - 1540, lime wood

Meester van het Nenkersdorfer retabel (Mathias Plaver?), Adoration of the Magi, Retable with on the Painted Exterior St. Agnes and St. Genovefa of Paris, ca. 1505 - 1510. The second image shows the backside of the retable.

Meester van het Nenkersdorfer retabel (Mathias Plaver?), Adoration of the Magi, Retable with on the Painted Exterior St. Agnes and St. Genovefa of Paris, ca. 1505 - 1510. The second image shows the backside of the retable.

Jocques Greffier, Book of Hours with miniatures with writing of three different handwritings, 1503

Jocques Greffier, Book of Hours with miniatures with writing of three different handwritings, 1503

Book of Hours (Horarium), 15th c.

Book of Hours (Horarium), 15th c.

Modern art and the “sacred without religion”

Much of the modern and contemporary art presented in the Bonnefanten Museum operates without reference to religious tradition or doctrinal content. Yet many works seem to aim at something structurally similar to religious experience: moments of stillness, detachment, or heightened presence. Minimalist sculptures, installations built around silence or emptiness, and time-based media that resist quick consumption all invite a mode of engagement that suspends distraction and encourages focused attention. The terms may have changed: transcendence becomes presence, meditation becomes perception. But the underlying structure remains recognizable.

This becomes particularly clear when comparing such works to the spatial experience in the Basilica of St. Servatius. In both contexts, architectural and material elements shape how the visitor moves, looks, and listens. In both, light is controlled to produce contrast and focus; scale is used to induce awe or intimacy; and isolation is built into the framing of objects or spaces. What differs is the interpretive framework. In the basilica, these elements support a theological narrative tied to sanctity, intercession, and tradition. In the museum, they operate within a secular logic, aimed at aesthetic concentration or existential reflection, without assigning ultimate meaning.

From a Buddhist perspective, this difference is less decisive than it might appear. What matters is not whether a space is formally religious, but whether it enables attentiveness. Both the basilica and the museum construct conditions under which perception is slowed and habitual responses are suspended. Both make use of contrast, delay, and framing to draw the viewer into a state of presence. That state does not require metaphysical assumptions. It can be observed, entered, and left again without commitment to belief.

This is not to say that sacredness and aesthetic experience are interchangeable. But it does suggest that certain perceptual structures recur across domains, and that their effects can be analyzed without collapsing into either religious affirmation or secular dismissal. The Bonnefanten, in its modern galleries, does not claim to offer salvation or truth. But it does offer settings in which clarity, openness, and resonance become possible. In that sense, it participates without proclamation in a long history of spaces designed to focus attention and invite reflection.

Selected religious artworks (continued)

Male saint, France (Limoges), 13h century, Champlevé enamel and copper-gilt.

Male saint, France (Limoges), 13h century, Champlevé enamel and copper-gilt.

Crucifix from an altar or processional cross, France (Limoges), mid-13 century, Champlevé enamel on copper-gilt.

Crucifix from an altar or processional cross, France (Limoges), mid-13 century, Champlevé enamel on copper-gilt.

Griffin, Rhineland (Cologne?), 12th century, Copper, gilded

Griffin, Rhineland (Cologne?), 12th century, Copper, gilded

Christ as judge at the Last Fudgment, France (Paris), 2nd quarter of 14h century, Ivory

Christ as judge at the Last Fudgment, France (Paris), 2nd quarter of 14h century, Ivory

Virgin and Child, France, 2nd quarter of 14h century, Ivory

Virgin and Child, France, 2nd quarter of 14h century, Ivory

Christ as fudge, France, mid-14th century, Ivory

Christ as fudge, France, mid-14th century, Ivory

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary, English Midlands, 4th quarter of 15h century Alabaster, polychromy

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary, English Midlands, 4th quarter of 15h century Alabaster, polychromy

Caput lohannis in Disco, England (Nottingham), 2nd half of 15th century, Alabaster, polychromy

Caput lohannis in Disco, England (Nottingham), 2nd half of 15th century, Alabaster, polychromy

Betrayal of Christ, England (Nottingham), 15th century, Alabaster

Betrayal of Christ, England (Nottingham), 15th century, Alabaster

Caput Iohannis in Disco surrounded by saints, England (Nottingham), 2nd half of 15th century Alabaster, traces of polychromy

Caput Iohannis in Disco surrounded by saints, England (Nottingham), 2nd half of 15th century Alabaster, traces of polychromy

Virgin, Middle Rhine Valley, 2nd half of 14th century, Walnut, polychromy

Virgin, Middle Rhine Valley, 2nd half of 14th century, Walnut, polychromy

Christ’s Fall under the Cross Brussels (?), 1st quarter of 16th century

Christ’s Fall under the Cross Brussels (?), 1st quarter of 16th century

Fragment of an altarpiece showing the Flight into Egypt, Northern Netherlands (Utrecht?), c. 1500, Oak

Fragment of an altarpiece showing the Flight into Egypt, Northern Netherlands (Utrecht?), c. 1500, Oak

Fragment of an altarpiece showing the Circumcision, Netherlands (Utrecht?), 4th quarter of 15th century - yst quarter of 16th century, Oak

Fragment of an altarpiece showing the Circumcision, Netherlands (Utrecht?), 4th quarter of 15th century - yst quarter of 16th century, Oak

Left: Christ on the Cold Stone, Brabant (Leuven?), 1st quarter of 16th century, Oak, polychromyChrist on the Cold Stone, Brabant (Leuven?), 1st quarter of 16th century, Oak, polychromy. Right: Standing figure of the Virgin, Brabant, 2nd half of 15th centurym Walnut, remains of polychromy.

Left: Christ on the Cold Stone, Brabant (Leuven?), 1st quarter of 16th century, Oak, polychromyChrist on the Cold Stone, Brabant (Leuven?), 1st quarter of 16th century, Oak, polychromy. Right: Standing figure of the Virgin, Brabant, 2nd half of 15th centurym Walnut, remains of polychromy.

Christ on the Cold Stone, Mechelen, 1st quarter of 16th century, Walnut, polychromy

Christ on the Cold Stone, Mechelen, 1st quarter of 16th century, Walnut, polychromy

Enthroned Virgin and Child with St Anne, Mechelen?, c. 1500, Oak (case), walnut (figures), polychromy

Enthroned Virgin and Child with St Anne, Mechelen?, c. 1500, Oak (case), walnut (figures), polychromy

Last Supper, Mechelen, 3rd quarter of 16th century, Alabaster with traces of brown and gold paint

Last Supper, Mechelen, 3rd quarter of 16th century, Alabaster with traces of brown and gold paint

The Bonnefanten as cultural mediator

I think, that the Bonnefanten Museum occupies a position that is not only architectural or curatorial, but also civic. As a public institution, it brings together elements of Maastricht’s cultural history that might otherwise remain separate: Religious heritage, European painting, modernist experimentation, and contemporary global perspectives. In doing so, it acts as a mediator, not between artworks in a theoretical sense, but between different temporalities, value systems, and audiences.

Unlike the Basilica of St. Servatius, which continues to function as a religious space shaped by liturgy and tradition, the Bonnefanten is a secular institution. It preserves Christian art as part of the city’s visual and material past, but without doctrinal continuity. At the same time, it provides a platform for contemporary voices that may be critical, speculative, or simply unrelated to European tradition. The result is not a unified narrative but a curated coexistence, in which visitors are invited to observe difference and make connections without being told how to resolve them.

This role becomes particularly significant in a city like Maastricht, where historical depth and geopolitical positioning have long made cultural negotiation a lived reality. The juxtaposition of basilica and museum reflects a broader European pattern: The coexistence of religious institutions, secular archives, and experimental spaces within shared urban settings. These juxtapositions are not merely aesthetic. They raise questions about how societies remember, reinterpret, and transmit meaning across generations.

The Bonnefanten does not dissolve these tensions, instead it stages them. Its architecture separates sacred from secular, but its programming places them in proximity. It holds Christian devotional objects not in opposition to modern art, but alongside it, as part of a wider visual culture that continues to evolve. In this way, the museum becomes a site not of resolution, but of ongoing negotiation. It reflects how European cities like Maastricht manage the transition from heritage to present, from tradition to experiment, without needing to erase either side.

Conclusion

Visiting the Basilica of St. Servatius and the Bonnefanten Museum on the same day makes it unusually clear how sacredness, meaning, and attention are not fixed qualities but effects, produced through architecture, staging, and institutional framing. Both spaces rely on similar perceptual mechanisms: Light modulation, spatial hierarchy, material emphasis, and rhythm. Both cultivate an atmosphere that separates them from everyday environments and asks for a slower, more attentive form of engagement.

What differs is not how the experience is constructed, but how it is interpreted. In the basilica, spatial cues are embedded in a theological framework that assigns fixed meaning to ritual and object. In the museum, the same cues are used to support reflection, ambiguity, or aesthetic focus, without resolving them into doctrine. The underlying mechanisms are shared; the narratives that surround them are not.

Seeing both places in sequence draws this distinction into focus. It highlights how meaning is historically constructed and culturally maintained, even when the tools used to create it remain stable over time. At the same time, it shows that presence, silence, and perceptual clarity are not bound to religion. They emerge wherever space is structured to support them. This does not flatten the difference between sacred and secular, but it clarifies how both operate, and what they make possible.

References and further reading

- Aldo Rossi, The architecture of the city, 1984, MIT Press, ISBN: 978-0262181013

- Aldo Rossi, A scientific autobiography (reissue), 2010, MIT Press, ISBN: 978-0262514385

- H. G. Hannesen, Aldo Rossi: architect, 1994, Laurence King, ISBN: 1854903640

- Carol Duncan, Civilizing rituals: inside public art museums, 1995, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415070126

- Brian O’Doherty, Inside the white cube: the ideology of the gallery space, 2000, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520220409

- Tony Bennett, The birth of the museum: history, theory, politics, 1995, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415053884

- Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the shaping of knowledge, 1992, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415070317

- Hans Belting, Likeness and presence: a history of the image before the era of art, 1997, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226042152

- James Elkins, On the strange place of religion in contemporary art, 2004, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415969895

- David Morgan, The sacred gaze: religious visual culture in theory and practice, 2005, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520243064

- Bonnefantenmuseum, Bonnefanten museum (collection guide), 1995, Bonnefantenmuseum, ISBN: 978-9072251190

- Kim Knott, The location of religion: a spatial analysis, 2005, Routledge, ISBN: 978-1844657490

- Daniel A. Siedell, God in the gallery: a Christian embrace of modern art, 2008, Baker Academic, ISBN: 978-0801031847

comments