Jianfeng Pan: An ink wanderer between cultures

In April 2025, I visited the exhibition Ink Roamings. Contemporary works on paper by Jianfeng Pan (2014–2024) at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln. The exhibition presented around sixty works on paper produced over the past decade by the Chinese ink artist Jianfeng Pan (b. 1973), ranging from monumental hanging scrolls to small album formats and serial works. In this post, I summarize what I have seen and learned from the exhibition.

Entrance into the exhibition ‘Ink Roamings. Contemporary works on paper by Jianfeng Pan’, 2014-2024. Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln.

Entrance into the exhibition ‘Ink Roamings. Contemporary works on paper by Jianfeng Pan’, 2014-2024. Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln.

Artist background

Pan’s artistic position is shaped by multiple trajectories. Trained in graphic design and formerly based in Shanghai, he has lived in Finland since 2016 in what he describes as self-exile. His work is deeply rooted in the historical arts of Chinese writing and painting, while at the same time absorbing visual impressions from Northern European landscapes, everyday culture, and contemporary graphic language. The resulting imagery oscillates between forceful, almost graffiti-like gestures and quieter, contemplative passages. Throughout, Pan understands ink not as a regional or historical medium, but as a global visual language capable of articulating social, philosophical, and existential questions.

Material practice and exhibition design

A striking aspect of the exhibition is its emphasis on materiality. All mounting formats were conceived and produced by the artist specifically for this presentation. Classical hanging scrolls appear alongside experimental floating scrolls, wood-framed sheets, folding screens, handscrolls extending over thirteen meters, and compact fanfold books displayed in vitrines.

This focus draws attention not only to the images themselves but to their physical support structures: brush, ink, paper, and mounting. The exhibition thus foregrounds the conditions of image production and reception, situating Pan’s work firmly within the material logic of Chinese brush-and-ink traditions while allowing for contemporary experimentation.

Self-Portrait as performance

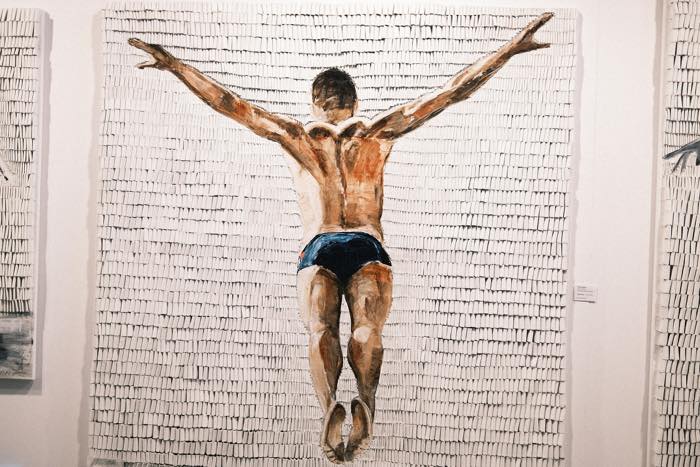

A central work at the entrance of the exhibition is Self-Portrait (2025), created during a live action writing performance at the exhibition opening. The larger-than-life human figure was executed using the three elementary media of traditional Chinese literati art: brush, ink, and paper. Pan worked with a one-meter-long Chinese brush made of horsetail hair, approximately 20 liters of liquid ink, and ten assembled sheets of xuan paper.

Self-Portrait 2025, Chinese ink on xuan-paper, 10 assembled sheets, Total dimensions ca. 390 x 350 cm. From the exhibition ‘Ink Roamings. Contemporary works on paper by Jianfeng Pan’, 2014-2024. Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln.

Self-Portrait 2025, Chinese ink on xuan-paper, 10 assembled sheets, Total dimensions ca. 390 x 350 cm. From the exhibition ‘Ink Roamings. Contemporary works on paper by Jianfeng Pan’, 2014-2024. Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln.

Although the term “self-portrait” suggests a pictorial genre, the work is grounded neither in representation nor in painterly modeling. Instead, its technique and composition are rooted in Chinese calligraphy (shufa), the art of writing from which ink painting historically emerged. Pan’s brushstrokes are placed with force and in rapid, decisive sequences, emphasizing movement and bodily presence rather than likeness.

Video installation showing Jianfeng Pan’s Live Action Writing Performance creating Self-Portrait 2025 at the exhibition opening.

Video installation showing Jianfeng Pan’s Live Action Writing Performance creating Self-Portrait 2025 at the exhibition opening.

In the classical tradition, shufa is understood not as “beautiful writing,” but as a disciplined method of writing cultivated by scholar-artists (wenren), based on the unity of physical gesture and inner disposition. The brush functions as an organic extension of the body. Pan explicitly adopts this conception in his performative practice, describing the act of writing as a process of becoming part of the image itself. His statement “My body is the best brush” encapsulates this position. The Self-Portrait thus operates as a contemporary homage to the classical ideal of the unison of hand and heart, translated into a public, time-based action.

‘Self-Portrait’ hanging in the entrance area of the exhibition.

‘Self-Portrait’ hanging in the entrance area of the exhibition.

Exhibition rooms

The exhibition was organized into three thematic rooms, each exploring different facets of Pan’s ink practice.

Exhibition Room II: Inversive Ink.

Exhibition Room II: Inversive Ink.

Room I: Roaming Ink

The first exhibition space, Roaming Ink, was dominated by large-scale works and addresses the Daoist concept of xiaoyao you, carefree roaming beyond fixed boundaries, as described in the Zhuangzi. Pan’s key work Northern Ocean refers to the mythical transformation of a primordial fish into a giant bird, a figure for radical change and boundless movement.

This Daoist imagery is juxtaposed with Ragnarök, whose title references Scandinavian mythology. Here, Pan introduces Chinese blue mineral pigment into the ink composition, linking cosmological ideas from different cultural traditions. Rather than illustrating specific narratives, these works explore notions of origin, transformation, and indeterminate substance. The philosophical concept of the All-Encompassing Brushstroke (yihua), formulated by the Qing-dynasty painter Shitao, provides an underlying framework: a single, primordial stroke that simultaneously contains and differentiates the cosmos.

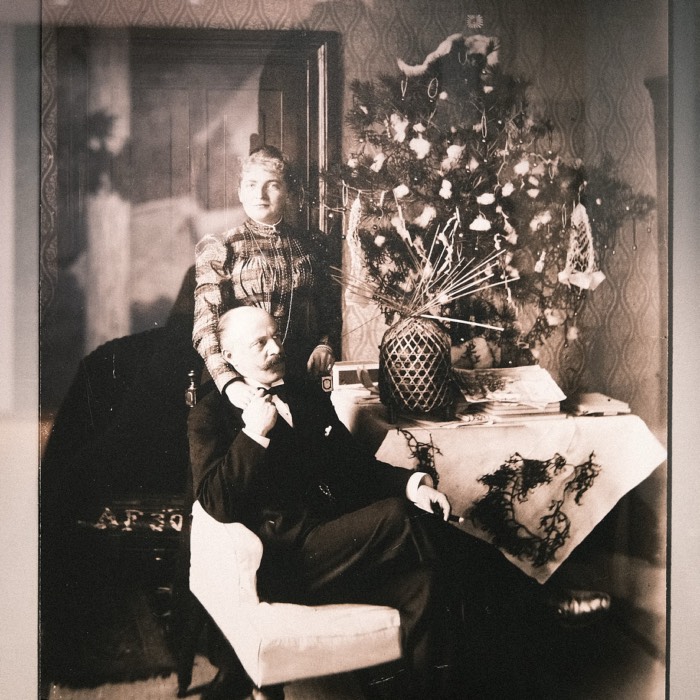

Farewell to My Father, 2016-2021, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 11 assembled sheets, total dimensions 180 x 1045 cm. Farewell to My Father is a dialogue between Jianfeng Pan and his father, who passed away in 2016. The opus stretches spatially over a more than ten-meter-long paper surface, temporally over a more than five-year-long creation process. In his farewell, Pan chooses the language of the calligraphic brush, the technical skills of which he learned from his father Zhishan Pan (1946-2016) as a child. Originally from Ruian in Zhejiang Province, his father was o dedicated and respected calligrapher of his time. In old age, he lost the ability to write by hand and became known for his ink art written and painted with his toes. Jianfeng Pan’s ‘Farewell’ poses the question whether son and father are more closely connected to, or more separated from one another after death.

Farewell to My Father, 2016-2021, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 11 assembled sheets, total dimensions 180 x 1045 cm. Farewell to My Father is a dialogue between Jianfeng Pan and his father, who passed away in 2016. The opus stretches spatially over a more than ten-meter-long paper surface, temporally over a more than five-year-long creation process. In his farewell, Pan chooses the language of the calligraphic brush, the technical skills of which he learned from his father Zhishan Pan (1946-2016) as a child. Originally from Ruian in Zhejiang Province, his father was o dedicated and respected calligrapher of his time. In old age, he lost the ability to write by hand and became known for his ink art written and painted with his toes. Jianfeng Pan’s ‘Farewell’ poses the question whether son and father are more closely connected to, or more separated from one another after death.

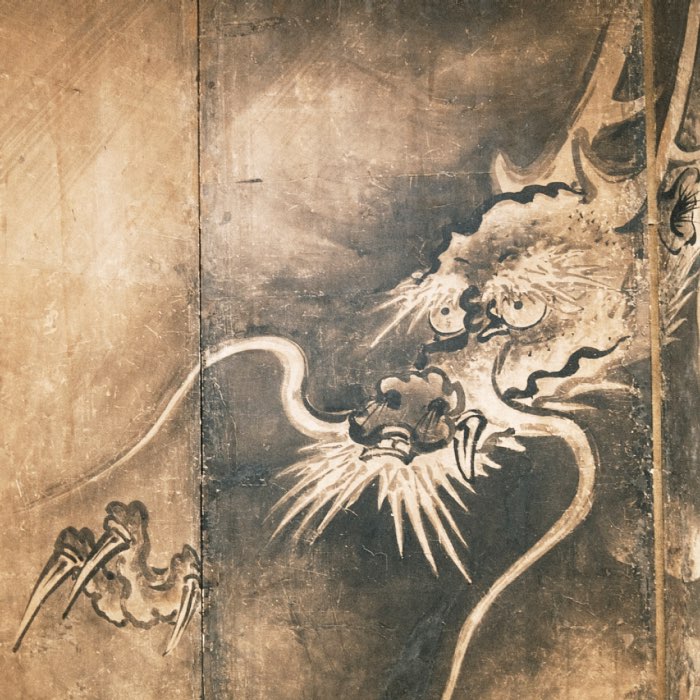

Northern Ocean, 2023, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 3 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 230 x 71 cm. The title ‘Northern Ocean’ refers to the Daoist classic Zhuangzi, in which the abyssal ‘Northern Sea’ - or ‘Northern Darkness’ - is introduced as a mythical shadowy place of incomprehensible dimension and capacity. The first book chapter, ‘Carefree Roaming Afar’ (Xiaoyao you), tells of mind travel and mystical exploration of the world beyond known boundaries. And indeed, the longer one looks and lets one’s own gaze wander, the more one discovers in Pan’s deep-black sea: eyes, mouths, and faces, small and large creatures reminiscent of jellyfish and amphibians, platypuses and reptiles. A dragon coils itself at the center like a vortex. The literary topos of ‘carefree roaming’ permeates the art and cultural history of East Asia up to the present day, as Pan’s visual translation exemplifies.

Northern Ocean, 2023, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 3 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 230 x 71 cm. The title ‘Northern Ocean’ refers to the Daoist classic Zhuangzi, in which the abyssal ‘Northern Sea’ - or ‘Northern Darkness’ - is introduced as a mythical shadowy place of incomprehensible dimension and capacity. The first book chapter, ‘Carefree Roaming Afar’ (Xiaoyao you), tells of mind travel and mystical exploration of the world beyond known boundaries. And indeed, the longer one looks and lets one’s own gaze wander, the more one discovers in Pan’s deep-black sea: eyes, mouths, and faces, small and large creatures reminiscent of jellyfish and amphibians, platypuses and reptiles. A dragon coils itself at the center like a vortex. The literary topos of ‘carefree roaming’ permeates the art and cultural history of East Asia up to the present day, as Pan’s visual translation exemplifies.

Ragnarök, 2024, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 3 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 370 x 100 cm. Pan envisions the mythology of Scandinavia. The saga Ragnarök, whose Old Norse name literally means ‘Fate of the Gods’, tells of the catastrophic end of the world after the gods lose their battle against demons and giants. The killing of the God of Light at the beginning of the saga heralds the end of the world with a merciless ‘Fimbulwinter’ (‘Mighty Winter’) lasting three years. The earth dies down in darkness, and is finally reborn. Using ink in combination with Chinese mineral color, Pan captures what he calls the ‘Finnish Blue Moment’: the culmination point shortly before the onset of winter and entry into the dark season; a retreat inwards and stoic waiting for the next spring.

Ragnarök, 2024, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 3 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 370 x 100 cm. Pan envisions the mythology of Scandinavia. The saga Ragnarök, whose Old Norse name literally means ‘Fate of the Gods’, tells of the catastrophic end of the world after the gods lose their battle against demons and giants. The killing of the God of Light at the beginning of the saga heralds the end of the world with a merciless ‘Fimbulwinter’ (‘Mighty Winter’) lasting three years. The earth dies down in darkness, and is finally reborn. Using ink in combination with Chinese mineral color, Pan captures what he calls the ‘Finnish Blue Moment’: the culmination point shortly before the onset of winter and entry into the dark season; a retreat inwards and stoic waiting for the next spring.

Cartoon ‘Early Spring’, 2017, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, mounted hanging scroll, 270 x 180 cm. The work pays tribute to the great tradition of Chinese landscape painting, which flourished during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1279) and shaped the iconic format of the monumental hanging scroll. The classical pictorial genre known as, literally, ‘mountain-water-painting’ (shanshuihua), aims at a microcosmic representation of the macrocosmic world order: a universe in miniature, to be wandered through by the viewer before their mind’s eye. Compositionally, the path leads through the painted nature landscape beginning in the densely vegetated foreground in the lower part of the picture, across mist-shrouded streams in the middle ground at the picture center, high up to the mountain peaks, which dissolve into the clouds and open sky in the upper part of the picture. Pan’s work is based on the masterpiece Early Spring of 1072 by the court pointer Guo Xi. In keeping with the maxim ‘study the old to create the new’ (xue gu chuang xin), the vibrant ink lines of Pan’s cartoon-like interpretation awaken the Song-dynasty original to new life.

Cartoon ‘Early Spring’, 2017, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, mounted hanging scroll, 270 x 180 cm. The work pays tribute to the great tradition of Chinese landscape painting, which flourished during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1279) and shaped the iconic format of the monumental hanging scroll. The classical pictorial genre known as, literally, ‘mountain-water-painting’ (shanshuihua), aims at a microcosmic representation of the macrocosmic world order: a universe in miniature, to be wandered through by the viewer before their mind’s eye. Compositionally, the path leads through the painted nature landscape beginning in the densely vegetated foreground in the lower part of the picture, across mist-shrouded streams in the middle ground at the picture center, high up to the mountain peaks, which dissolve into the clouds and open sky in the upper part of the picture. Pan’s work is based on the masterpiece Early Spring of 1072 by the court pointer Guo Xi. In keeping with the maxim ‘study the old to create the new’ (xue gu chuang xin), the vibrant ink lines of Pan’s cartoon-like interpretation awaken the Song-dynasty original to new life.

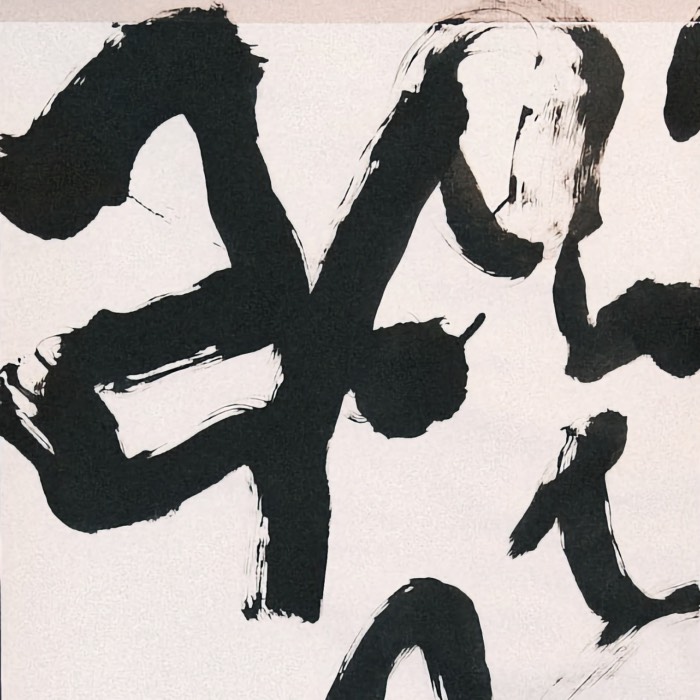

Unregistered Calligraphy, 2024, ‘Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 5 mounted hanging scrolls with 3 sheets each, each scroll 350 x 60 cm. The continuous reversal and balancing of opposite poles are a trademark of Pan’s ink art: between written and unwritten paper surface, straight and curved brushstrokes, greyish-pale and deep-black ink tones, coarse and fine lines. Pan’s serially created works visualize these dynamic fields of tension particularly vividly. The 15 selected works from the Unregistered Calligraphy series are specially mounted and installed by him in ‘floating’ technique for the exhibition. Together, the five hanging scrolls, each integrating three sheets, can be read like a calligraphic artwork - from top to bottom, and right to left. The ink renderings thus combined to form a complete ‘text’ could stand for 15 imaginary written characters. Pan deliberately strips his characters of any semantic content. Rather, the story is told through the narrative lines of the brushstrokes, technically executed in both pattern-book and playful manner, becoming carriers of meaning themselves. Their graphic forms subtly evoke the natural world, from gnarled roots and barren mountains, to snow-covered branches, bubbling springs, and delicately blooming buds.

Unregistered Calligraphy, 2024, ‘Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 5 mounted hanging scrolls with 3 sheets each, each scroll 350 x 60 cm. The continuous reversal and balancing of opposite poles are a trademark of Pan’s ink art: between written and unwritten paper surface, straight and curved brushstrokes, greyish-pale and deep-black ink tones, coarse and fine lines. Pan’s serially created works visualize these dynamic fields of tension particularly vividly. The 15 selected works from the Unregistered Calligraphy series are specially mounted and installed by him in ‘floating’ technique for the exhibition. Together, the five hanging scrolls, each integrating three sheets, can be read like a calligraphic artwork - from top to bottom, and right to left. The ink renderings thus combined to form a complete ‘text’ could stand for 15 imaginary written characters. Pan deliberately strips his characters of any semantic content. Rather, the story is told through the narrative lines of the brushstrokes, technically executed in both pattern-book and playful manner, becoming carriers of meaning themselves. Their graphic forms subtly evoke the natural world, from gnarled roots and barren mountains, to snow-covered branches, bubbling springs, and delicately blooming buds.

Room II: Inversive Ink

The second space, Inversive Ink, focused on Pan’s technical experiments with inversion and duality. Drawing on long-standing East Asian traditions that emphasize emptiness as an active compositional element, Pan develops a method he describes as “paper on ink”.

In this process, water is applied to the front of the paper, while diluted ink is brushed onto the reverse. The absorbent xuan paper mediates between both, producing gradients and textures that escape full control. The conventional hierarchy of ink acting upon passive paper is thus reversed. Paper becomes an active participant through its capacity to absorb, resist, and transform. Pan’s self-description as a “background painter” reflects this inversion, aligning the method with Daoist notions of wuwei, non-action as productive force.

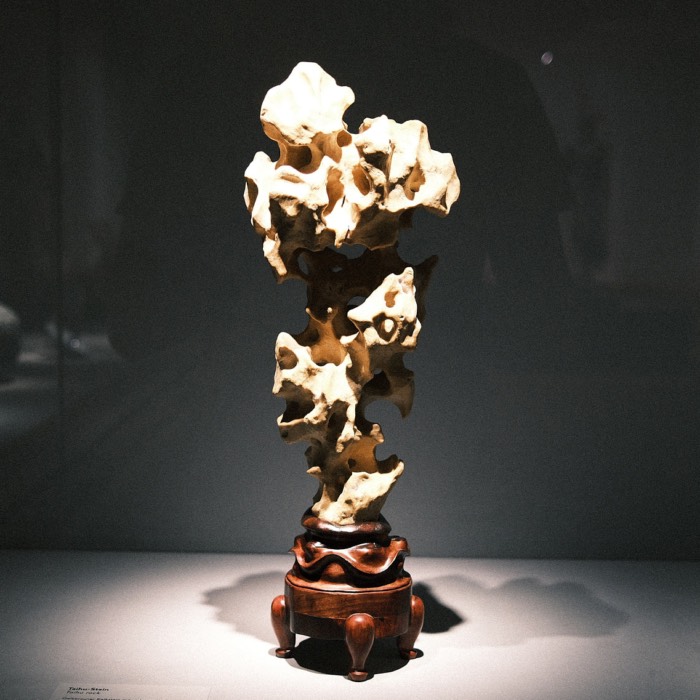

Your Problem Is Mine, 2024, ‘Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 3 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 370 x 74 cm. The work mounted in the form of three hanging scrolls and enigmatically titled ‘Your Problem is Mine,’ can, like Lost and Found, be presented in vertical or horizontal format. Shown here is the horizontal viewing perspective. Pan’s motif reminiscent of a sharp-edged, cavitous rock structure is inspired by the handed-down story of Bodhidharma (5th/ 6th c.): the legendary founder of Chan, respectively Zen Buddhism, who traveled from India to China and is said to have meditated in front of a cave wall for nine years, even after his arms, legs, and eyelids had fallen off Iconographically, the portrait of the master sitting before the stone wall in contemplation is widespread throughout East Asia. Pan’s work induces a reversal of perspective: instead of the typical depiction of Bodhidharma meditating, we ourselves become the sitter in the cave, gazing straight at the wall before us, self-reflexively.

Your Problem Is Mine, 2024, ‘Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 3 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 370 x 74 cm. The work mounted in the form of three hanging scrolls and enigmatically titled ‘Your Problem is Mine,’ can, like Lost and Found, be presented in vertical or horizontal format. Shown here is the horizontal viewing perspective. Pan’s motif reminiscent of a sharp-edged, cavitous rock structure is inspired by the handed-down story of Bodhidharma (5th/ 6th c.): the legendary founder of Chan, respectively Zen Buddhism, who traveled from India to China and is said to have meditated in front of a cave wall for nine years, even after his arms, legs, and eyelids had fallen off Iconographically, the portrait of the master sitting before the stone wall in contemplation is widespread throughout East Asia. Pan’s work induces a reversal of perspective: instead of the typical depiction of Bodhidharma meditating, we ourselves become the sitter in the cave, gazing straight at the wall before us, self-reflexively.

Double Black Happiness, 2023, ‘Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 2 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 215 x 71 cm. The double format of two coupled hanging scrolls has special cultural historical significance in China. As large-size carriers of calligraphic inscriptions transporting auspicious messages, these are hung together on festive occasions such as New Year or weddings. In Pans pair of hanging scrolls, likewise, the abstract white masses that seem to float freely in deep-black space belong together and form two parts of a whole. Astronomically, the structure visually evokes the remains of a superstar cluster in outer space; anatomically, perhaps an organic heart or even pair of hearts. In the particular discourse of Chinese ink art, the aspects of doubling and multi-plication, mirroring and repetition conjure the philosophically coined concept of the ‘All-Encompassing Brushstroke’ (yihua): the primordial brushstroke that still contains the entire cosmos in itself and forms the source of all subsequent brushstrokes. Technically, the title ‘Double Black Happiness’ may allude to Pan’s inversive ink technique - the twofold processing of the paper surface, first of its backside, then frontside.

Double Black Happiness, 2023, ‘Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 2 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 215 x 71 cm. The double format of two coupled hanging scrolls has special cultural historical significance in China. As large-size carriers of calligraphic inscriptions transporting auspicious messages, these are hung together on festive occasions such as New Year or weddings. In Pans pair of hanging scrolls, likewise, the abstract white masses that seem to float freely in deep-black space belong together and form two parts of a whole. Astronomically, the structure visually evokes the remains of a superstar cluster in outer space; anatomically, perhaps an organic heart or even pair of hearts. In the particular discourse of Chinese ink art, the aspects of doubling and multi-plication, mirroring and repetition conjure the philosophically coined concept of the ‘All-Encompassing Brushstroke’ (yihua): the primordial brushstroke that still contains the entire cosmos in itself and forms the source of all subsequent brushstrokes. Technically, the title ‘Double Black Happiness’ may allude to Pan’s inversive ink technique - the twofold processing of the paper surface, first of its backside, then frontside.

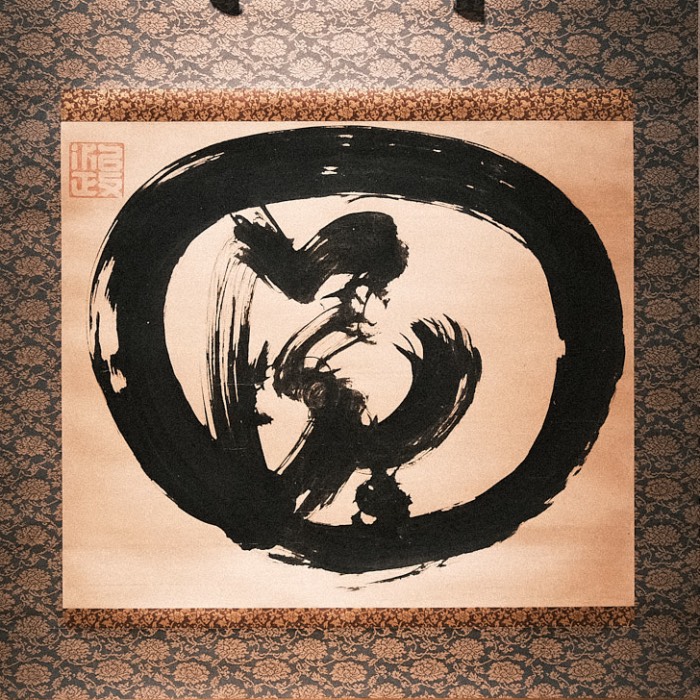

Hanging Inspirations, 2021, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 3 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 130 x 37 cm. In minimalist and flawless manner, Pan’s Hanging Inspirations fuse the elementary graphic forms of the centrally placed circle and rectangle that frames the image. Forming a visual contrast surface, they highlight emptiness as a constitutive part of the visual composition, condensing what is known in ink discourse as the ‘dialectical conversation between black and white’! The centered iconic round figure evokes the hand-drawn ‘Circle of Enlightenment’ (Jap. Enso), which was established in the calligraphic practice of Zen-Buddhist monks as an iconographic tradition.

Hanging Inspirations, 2021, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 3 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 130 x 37 cm. In minimalist and flawless manner, Pan’s Hanging Inspirations fuse the elementary graphic forms of the centrally placed circle and rectangle that frames the image. Forming a visual contrast surface, they highlight emptiness as a constitutive part of the visual composition, condensing what is known in ink discourse as the ‘dialectical conversation between black and white’! The centered iconic round figure evokes the hand-drawn ‘Circle of Enlightenment’ (Jap. Enso), which was established in the calligraphic practice of Zen-Buddhist monks as an iconographic tradition.

Midsummer 2023 I, ‘Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, wood, 6-panel standing screen, total dimensions 139 x 420 cm. The seasons, and the anticipation of seasonal transitions are recurring motifs in Pan’s work. While Ragnarök, for example, suggests anxiety about the approaching winter, Cartoon ‘Early Spring’ expresses the delights of renewal in spring. Pan’s extensive series Midsummer, then, sings an ode to the summertime, which in Scandinavia reaches its climax and is celebrated lusciously on occasion of the summer solstice, the longest day of the year around the end of June. The midsummer roses depicted on the folding screens are based on the plants in Pan’s own garden. Since moving into his house in the Finnish Porvoo in 2016, he paints the bushes of the Finnish wild rose, also known as Rosa pimpinellifolia Flora Plena, every year. As Pan notes, their usual two-week blooming period is shortening from year to year, which he ascribes to climate change. By painting the flowers, Pan seeks to document their disappearance in nature.

Midsummer 2023 I, ‘Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, wood, 6-panel standing screen, total dimensions 139 x 420 cm. The seasons, and the anticipation of seasonal transitions are recurring motifs in Pan’s work. While Ragnarök, for example, suggests anxiety about the approaching winter, Cartoon ‘Early Spring’ expresses the delights of renewal in spring. Pan’s extensive series Midsummer, then, sings an ode to the summertime, which in Scandinavia reaches its climax and is celebrated lusciously on occasion of the summer solstice, the longest day of the year around the end of June. The midsummer roses depicted on the folding screens are based on the plants in Pan’s own garden. Since moving into his house in the Finnish Porvoo in 2016, he paints the bushes of the Finnish wild rose, also known as Rosa pimpinellifolia Flora Plena, every year. As Pan notes, their usual two-week blooming period is shortening from year to year, which he ascribes to climate change. By painting the flowers, Pan seeks to document their disappearance in nature.

Unlimited, 2018-2020, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral colors, xuan-paper, cardboard, 20 assembled sheets mounted as a fanfold-book, total dimensions 45 × 1360 cm. Unlimited is inspired by what Pan calls the paradise village surroundings of his Finnish hometown, in an attempt to capture the, to him seemingly unreal pink of the early morning sky seen in the North in spring-time. All the same, the landscape remains essentially fictive; it springs from Pan’s imagination and does not represent any real existing natural setting. The ghostly creatures embedded in the scenery could be understood as haunting warning spirits that are meant to remind us of life and death in the everyday world - and the sometimes dangerous dream world in between. As the artist himself points out, his fanfold-book contains numerous hidden graphic elements. And as is usual in the Chinese pictorial tradition of narrative handscrolls, its stories unfold only when spread out and observed slowly.

Unlimited, 2018-2020, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral colors, xuan-paper, cardboard, 20 assembled sheets mounted as a fanfold-book, total dimensions 45 × 1360 cm. Unlimited is inspired by what Pan calls the paradise village surroundings of his Finnish hometown, in an attempt to capture the, to him seemingly unreal pink of the early morning sky seen in the North in spring-time. All the same, the landscape remains essentially fictive; it springs from Pan’s imagination and does not represent any real existing natural setting. The ghostly creatures embedded in the scenery could be understood as haunting warning spirits that are meant to remind us of life and death in the everyday world - and the sometimes dangerous dream world in between. As the artist himself points out, his fanfold-book contains numerous hidden graphic elements. And as is usual in the Chinese pictorial tradition of narrative handscrolls, its stories unfold only when spread out and observed slowly.

Room III: Mindful Ink

The final exhibition space, Mindful Ink, presented smaller works created during Pan’s travels: sketches, notes, caricatures, and short textual pieces. These works oscillate between humor, satire, and unease. Cartoon-like rabbits coexist with distorted human figures; playful surfaces give way to more ambiguous undertones upon closer inspection.

This room also integrates works in other media, including seal art, woodblock printing, ceramics, and graphic design. Together, they document Pan’s broader practice and his concept of “Mindful Ink”, which culminates in his internationally conducted One Breath workshops. The long-running series My Facebook, showed in the museum foyer, framed the exhibition spatially and thematically, reflecting on social media, communication, and contemporary forms of self-projection.

Self-Portrait, 2016, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, framed sheet 30 x 23 cm. The work from 2016 is only one among the many examples of Pan’s ‘Self-Portrait’ - the youngest one being the monumental work created in a live performance at the opening of this exhibition. The original ink sketch of the by now ubiquitous, logo-like image harks back to 2005. As Pan believes, the repetitive creation of the image as a form of ‘self-observation’ allows him to ‘get closer to who | am and really want to become’. The seal impression seen in the work is a glyphed transformation of the two Chinese characters jian (‘to see’) and feng (‘wind’), signifying the childhood name given to Pan by his father.

Self-Portrait, 2016, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, framed sheet 30 x 23 cm. The work from 2016 is only one among the many examples of Pan’s ‘Self-Portrait’ - the youngest one being the monumental work created in a live performance at the opening of this exhibition. The original ink sketch of the by now ubiquitous, logo-like image harks back to 2005. As Pan believes, the repetitive creation of the image as a form of ‘self-observation’ allows him to ‘get closer to who | am and really want to become’. The seal impression seen in the work is a glyphed transformation of the two Chinese characters jian (‘to see’) and feng (‘wind’), signifying the childhood name given to Pan by his father.

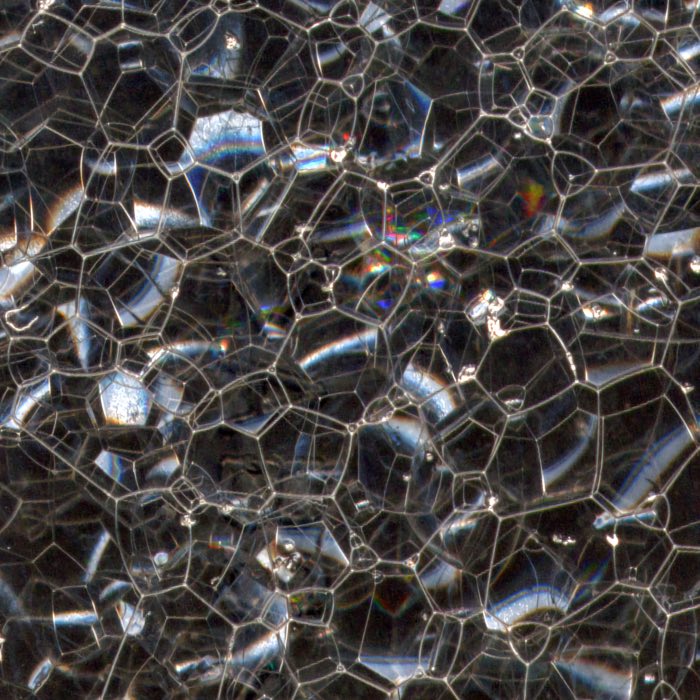

Northern Ocean, 2023’Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 3 framed sheets, each sheet 79 x 151 cm. The Northern Ocean series, created in connection with the eponymous large-format work shown in the first exhibition space, is inspired by Pan’s travels into the wild nature of Northern Scandinavia. For him, the travels bring to mind not only the free-spirited text ‘Carefree Roaming Afor’ from the Daoist classic Zhuangzi, but also the limitations of the hypertechnological age that shapes our existence today. Pan describes the creation of the series as a healing process: ‘I start by splashing water on the xuan-paper, then / turn the sheet over and work the backside with diluted, dark-grey ink. All I have to do then is continue painting the backside or the negative areas on the paper’s frontside. I so finally free myself from the self-image of the picture maker’ and happily become a ‘background painter’.

Northern Ocean, 2023’Paper-on-Ink’, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 3 framed sheets, each sheet 79 x 151 cm. The Northern Ocean series, created in connection with the eponymous large-format work shown in the first exhibition space, is inspired by Pan’s travels into the wild nature of Northern Scandinavia. For him, the travels bring to mind not only the free-spirited text ‘Carefree Roaming Afor’ from the Daoist classic Zhuangzi, but also the limitations of the hypertechnological age that shapes our existence today. Pan describes the creation of the series as a healing process: ‘I start by splashing water on the xuan-paper, then / turn the sheet over and work the backside with diluted, dark-grey ink. All I have to do then is continue painting the backside or the negative areas on the paper’s frontside. I so finally free myself from the self-image of the picture maker’ and happily become a ‘background painter’.

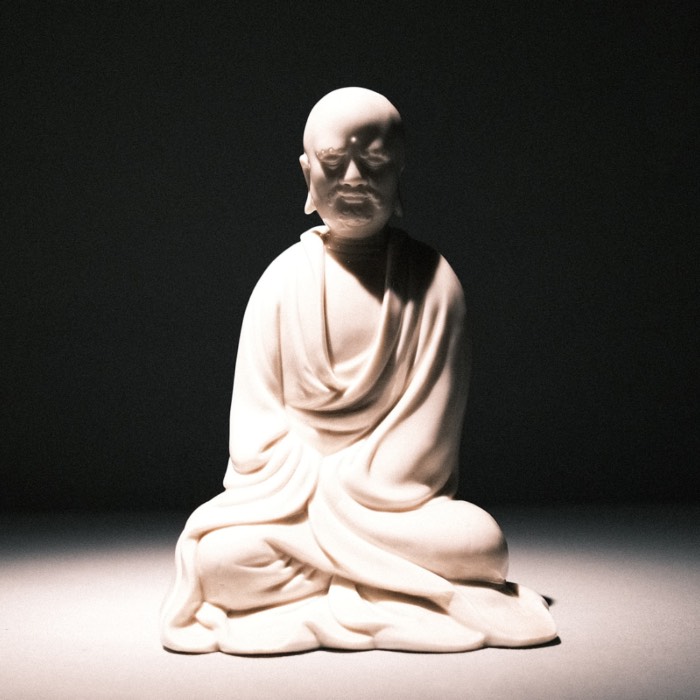

Self-Evolution, 2006, Blueish-white-glazed Jingdezhen Porcelain, 5 figurines, 12-15 x 12-15 cm. For Pan, clay and ink are closely related as ‘flowing, never fully graspable materials’. The plastic modeled images are created in 2006 during his study of porcelain production in Jingdezhen. The studies give him the opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the material of the ink medium and how to treat it. ‘The nature of the clay should never be hurt’. This first and most important lesson that Par learns with regard te ceramic production con, in his view be essentially transferred te the nature of ink and production of ink art.

Self-Evolution, 2006, Blueish-white-glazed Jingdezhen Porcelain, 5 figurines, 12-15 x 12-15 cm. For Pan, clay and ink are closely related as ‘flowing, never fully graspable materials’. The plastic modeled images are created in 2006 during his study of porcelain production in Jingdezhen. The studies give him the opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the material of the ink medium and how to treat it. ‘The nature of the clay should never be hurt’. This first and most important lesson that Par learns with regard te ceramic production con, in his view be essentially transferred te the nature of ink and production of ink art.

Ink Meditations, 2014, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 9 mounted album leaves, each leaf 35 x 35 cm.For Pan, 2014 was marked by intensive travels and a longer sojourn in Germany, particularly in the Hanseatic city of Hamburg. Pan describes the extensively created work series Ink Meditations, of which a small selection is shown, as a ‘visual diary’. It indicates his gradual departure from graphic design and decisive turning towards ink art. In terms of both motif and technique, Pan’s snapshot-like ink sketches can be contemplated as exercises in mindfulness. The brushstrokes are applied with deliberation and concentration, likewise effortlessly and playfully. No stroke is redundant, just as every left-out area of the picture plane is filled with meaning. Pan’s ‘ink meditations’ condense what is also known in the Chinese literati tradition as the esteemed art of so-called ‘ink play’ (moxi).

Ink Meditations, 2014, Chinese ink, xuan-paper, 9 mounted album leaves, each leaf 35 x 35 cm.For Pan, 2014 was marked by intensive travels and a longer sojourn in Germany, particularly in the Hanseatic city of Hamburg. Pan describes the extensively created work series Ink Meditations, of which a small selection is shown, as a ‘visual diary’. It indicates his gradual departure from graphic design and decisive turning towards ink art. In terms of both motif and technique, Pan’s snapshot-like ink sketches can be contemplated as exercises in mindfulness. The brushstrokes are applied with deliberation and concentration, likewise effortlessly and playfully. No stroke is redundant, just as every left-out area of the picture plane is filled with meaning. Pan’s ‘ink meditations’ condense what is also known in the Chinese literati tradition as the esteemed art of so-called ‘ink play’ (moxi).

My Hundred Longevities (1999), 1999, Chinese seal paste, xuan-paper, Original printed folding album 50 x 600 cm. The work carries 208 individually carved and printed graphic ciphers, evenly distributed in vertical rows. What appears upon first glance to be classical Chinese text, is in fact a corpus of ciphers containing letters from the Latin alphabet as well as globally known icons - including the communist hammer and sickle, dollar and euro symbols, paragraph and copyright signs, various Unicode characters, acronyms, western punctuation marks. Numerous ciphers represent variant renderings of the Chinese written character shou, ‘longevity’: some are based on historical types of ancient seal script, others on Pan’s pictographic imagination. Glyphs consisting entirely of horizontal lines may reference the divinatory 64 Hexagrams documented in the early Chinese Book of Changes (Yijing). My Hundred Longevities is created during Pan’s MA studies in Visual Communication at the Birmingham Institute of Art and De-sign, in an attempt to design a ‘universal language’. It combines western letterpress printing with the traditional Chinese folding-album format and makes use of cinnabar-based seal paste instead of ink.

My Hundred Longevities (1999), 1999, Chinese seal paste, xuan-paper, Original printed folding album 50 x 600 cm. The work carries 208 individually carved and printed graphic ciphers, evenly distributed in vertical rows. What appears upon first glance to be classical Chinese text, is in fact a corpus of ciphers containing letters from the Latin alphabet as well as globally known icons - including the communist hammer and sickle, dollar and euro symbols, paragraph and copyright signs, various Unicode characters, acronyms, western punctuation marks. Numerous ciphers represent variant renderings of the Chinese written character shou, ‘longevity’: some are based on historical types of ancient seal script, others on Pan’s pictographic imagination. Glyphs consisting entirely of horizontal lines may reference the divinatory 64 Hexagrams documented in the early Chinese Book of Changes (Yijing). My Hundred Longevities is created during Pan’s MA studies in Visual Communication at the Birmingham Institute of Art and De-sign, in an attempt to design a ‘universal language’. It combines western letterpress printing with the traditional Chinese folding-album format and makes use of cinnabar-based seal paste instead of ink.

My Hundred Longevities (2003), 2003, Fluorescent color, xuan-paper, silkscreen print 60 x 90 cm. After graduating from the China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, with an MA in Visual Communication in 1999, Pan completes a second MA degree at the University of Central England and Birmingham Institute of Art and Design. In 2001, he embarks on his career as graphic designer in Shanghai. Founded in his experimental research undertaken abroad, Pan’s focus on interactions between Chinese calligraphy and western typography prevails. His 2003 silkscreen poster print My Hundred Longevities, rendered in fluorescent pink, is a reproduction of the original folding album from 1999. The artist’s deep mindful connection with the three elementary materials of traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting - brush, ink, and paper - is shaped by his personal biography: from studying under the renowned Hangzhou-based modernist calligrapher Wong Dongling in young years; to realizing commissioned works for the Finnish Pavilion at the World Expo Shanghai 2010, Astana 2017, and Dubai 2021; to his dedicated work today as an intercultural agent of contemporary graphic ink art.

My Hundred Longevities (2003), 2003, Fluorescent color, xuan-paper, silkscreen print 60 x 90 cm. After graduating from the China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, with an MA in Visual Communication in 1999, Pan completes a second MA degree at the University of Central England and Birmingham Institute of Art and Design. In 2001, he embarks on his career as graphic designer in Shanghai. Founded in his experimental research undertaken abroad, Pan’s focus on interactions between Chinese calligraphy and western typography prevails. His 2003 silkscreen poster print My Hundred Longevities, rendered in fluorescent pink, is a reproduction of the original folding album from 1999. The artist’s deep mindful connection with the three elementary materials of traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting - brush, ink, and paper - is shaped by his personal biography: from studying under the renowned Hangzhou-based modernist calligrapher Wong Dongling in young years; to realizing commissioned works for the Finnish Pavilion at the World Expo Shanghai 2010, Astana 2017, and Dubai 2021; to his dedicated work today as an intercultural agent of contemporary graphic ink art.

Rabbit Hole, 2023-2025, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 8 framed album leaves, each leaf 36 x 25 / 25 x 36 / 79 x 53 cm. The series is created in 2023, the Chinese lunar Hare Year. It is inspired by the 1977 novel The Year of the Hare by the Finnish author Arto Paasilinna. Pan recognizes himself in its story: the protagonist, a work-weary media-person, encounters an injured rabbit as a result of a car accident and embarks on a life-changing - in Pan’s words - ‘journey of awakening’. In the form of self-carved woodblock-printing plates, Pan reproduces the image in infinite variations, each print bearing new visual aspects. Polychrome ink works implemented in his ‘paper-on-ink’ method complete the series and mirror its title - ‘Rabbit Hole’ It is not clear whether Pan’s rabbits disappear into the hole, or are born from it into the world. A brush-sketched ink rabbit is created in 2025 on occasion of the exhibition.

Rabbit Hole, 2023-2025, Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 8 framed album leaves, each leaf 36 x 25 / 25 x 36 / 79 x 53 cm. The series is created in 2023, the Chinese lunar Hare Year. It is inspired by the 1977 novel The Year of the Hare by the Finnish author Arto Paasilinna. Pan recognizes himself in its story: the protagonist, a work-weary media-person, encounters an injured rabbit as a result of a car accident and embarks on a life-changing - in Pan’s words - ‘journey of awakening’. In the form of self-carved woodblock-printing plates, Pan reproduces the image in infinite variations, each print bearing new visual aspects. Polychrome ink works implemented in his ‘paper-on-ink’ method complete the series and mirror its title - ‘Rabbit Hole’ It is not clear whether Pan’s rabbits disappear into the hole, or are born from it into the world. A brush-sketched ink rabbit is created in 2025 on occasion of the exhibition.

Unfinished Conversation, 2008-2022, Chinese ink, letter paper, 8 loose sheets, each sheet 29 x 21 cm. Pan’s Unfinished Conversation comprises a collection of around 150 research papers, of which a small selection is shown: graphic diagrams and mindmaps, exercises on Chinese script types and old masters’ styles, essayistic notes, introspective caricatures. They document Pan’s thoughtful intercultural and philosophical dealing with language and semiotics as well as the relationship between humans, nature, and art; commenting, for example, on the work of Ferdinand de Saussure, Rudolf Steiner, Yanagi Soetsu, and Jacques Derrida. As a brush-and-ink artist, Pan is fully aware of the remarkable phenomenon of the Chinese written language: here, the fascination with calligraphy lies in the fact that the visual form of the written character itself becomes meaningful, beyond its semantic value. Pan’s Unfinished Conversation, curiously rendered on letter paper he inherited from the owner of a Chinese restaurant in Turku, conveys the artist’s mindful multiverse in the form of his daily ‘food for thought’.

Unfinished Conversation, 2008-2022, Chinese ink, letter paper, 8 loose sheets, each sheet 29 x 21 cm. Pan’s Unfinished Conversation comprises a collection of around 150 research papers, of which a small selection is shown: graphic diagrams and mindmaps, exercises on Chinese script types and old masters’ styles, essayistic notes, introspective caricatures. They document Pan’s thoughtful intercultural and philosophical dealing with language and semiotics as well as the relationship between humans, nature, and art; commenting, for example, on the work of Ferdinand de Saussure, Rudolf Steiner, Yanagi Soetsu, and Jacques Derrida. As a brush-and-ink artist, Pan is fully aware of the remarkable phenomenon of the Chinese written language: here, the fascination with calligraphy lies in the fact that the visual form of the written character itself becomes meaningful, beyond its semantic value. Pan’s Unfinished Conversation, curiously rendered on letter paper he inherited from the owner of a Chinese restaurant in Turku, conveys the artist’s mindful multiverse in the form of his daily ‘food for thought’.

‘Facebook’ as seen through one of the windows of the museum.

‘Facebook’ as seen through one of the windows of the museum.

My Facebook (2014-), Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 2 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 180 x 97 cm. The two large-format works from Jianfeng Pan’s ongoing series My Facebook welcome and bid farewell to visitors to the special exhibition Tuschewanderungen (Ink Wanderings). Created in 2014, the same year the series began, they reflect Pan’s intensive travels, including to Germany. Mosaic-like, the large-scale compositions show hundreds of human faces: collective portraits of contemporary society, captured in different locations around the globe. Like personal entries in a diary, they document Pan’s perception of the individuals and living environments he encounters on his travels. He compares his miniature portraits to fingerprints. Viewed from a distance, they form a homogeneous mass, but on closer inspection, each face is unique, each profile different. With a few strokes of ink, Pan draws countless faces; some seem familiar, others strange.

My Facebook (2014-), Chinese ink, Chinese mineral color, xuan-paper, 2 mounted hanging scrolls, each scroll 180 x 97 cm. The two large-format works from Jianfeng Pan’s ongoing series My Facebook welcome and bid farewell to visitors to the special exhibition Tuschewanderungen (Ink Wanderings). Created in 2014, the same year the series began, they reflect Pan’s intensive travels, including to Germany. Mosaic-like, the large-scale compositions show hundreds of human faces: collective portraits of contemporary society, captured in different locations around the globe. Like personal entries in a diary, they document Pan’s perception of the individuals and living environments he encounters on his travels. He compares his miniature portraits to fingerprints. Viewed from a distance, they form a homogeneous mass, but on closer inspection, each face is unique, each profile different. With a few strokes of ink, Pan draws countless faces; some seem familiar, others strange.

Conclusion

Before I visited the exhibition, I did not know anything about Jianfeng Pan’s work. The show surprised me positively in many ways. First of all, I appreciated the clear curatorial concept that structured the exhibition into three thematic rooms, each with a distinct focus yet interconnected through Pan’s artistic practice. The spatial arrangement allowed for a gradual immersion into Pan’s world of ink art, from the grand landscapes to the intimate sketches.

Secondly, I was impressed by the diversity of techniques and formats employed by Pan. From large-scale fanfold books to small album leaves, from monochrome ink washes to vibrant mineral colors, Pan is a versatile artist who masters various forms of expression within the ink medium. The creativity displayed in his works is truly remarkable.

But what I liked most was that his art is rooted in Chinese writing and painting traditions. Especially by combining philosophical reference, experimentation, and contemporary elements, Pan creates a unique visual language that resonates with both Eastern and Western audiences I could imagine. His works invite contemplation and reflection, but also mind-trips into fantastical worlds.

Overall, Tuschewanderungen was a captivating exhibition that offered a comprehensive overview of Jianfeng Pan’s artistic journey and his contributions to contemporary ink art. It was a pleasure to explore his works and gain insights into his creative process. I left the museum feeling inspired and eager to explore more modern approaches to traditional art forms.

comments