Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 3/52

Buddhism and quantum physics: Parallels, projections, and problems

The intersection of Buddhism and quantum physics has sparked decades of fascination, debate, and philosophical inquiry. Both traditions, though arising from vastly different contexts, challenge classical notions of reality, separability, and permanence. Quantum physics, with its principles of uncertainty, superposition, and entanglement, has upended deterministic worldviews, while Buddhist philosophy, through concepts like dependent origination and emptiness, offers a relational and process-oriented understanding of existence. In this post, we explore the parallels, projections, and potential pitfalls of comparing these two frameworks. Rather than equating Buddhist insights with quantum mechanics, we seek to examine how each tradition can inform the other, fostering a deeper appreciation of the relational and dynamic nature of reality while respecting their distinct methodologies and aims.

Death, rebirth, and continuity of mind

The question of what happens at death has preoccupied human thought across cultures and epochs. In Buddhist philosophy, particularly as taught by Siddhartha Gautama, death is not seen as the annihilation of an eternal self, nor as the transmigration of a fixed soul, but as part of a continuous process of conditioned arising (paṭiccasamuppāda). This perspective offers a distinct alternative to both materialist annihilationism and metaphysical eternalism. Modern psychology and neuroscience, while refraining from metaphysical claims, also provide frameworks for understanding continuity without requiring an enduring self. In this post, we explore how Buddhist ideas of death and rebirth intersect with contemporary understandings of mind and memory.

Consciousness and the ‘hard problem’ from a Buddhist angle

The ‘hard problem’ of consciousness, famously articulated by philosopher David Chalmers (1995), refers to the difficulty of explaining how and why subjective experiences arise from physical processes in the brain. While modern neuroscience and philosophy of mind continue to struggle with this enigma, Buddhist thought, particularly as taught by Siddhartha Gautama and developed in later traditions, offers a radically different approach. Rather than positing consciousness as an inexplicable emergent property of matter or an irreducible substance, Buddhism treats consciousness as a contingent, dependently originated phenomenon (paṭiccasamuppāda). In this post, we explore how Buddhist philosophy reframes the hard problem, offering insights that challenge both reductionist materialism and metaphysical dualism.

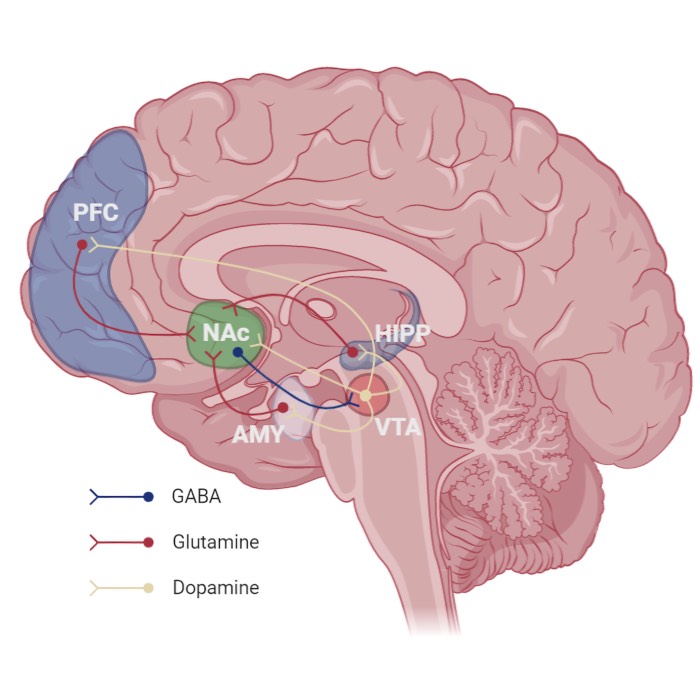

Suffering, craving, and the brain’s reward system

At the core of Siddhartha Gautama’s teachings lies the diagnosis that craving (taṇhā) is the origin of suffering (dukkha). This insight, articulated in the Four Noble Truths, portrays human dissatisfaction as arising from attachment to transient pleasures, possessions, and identities. Modern neuroscience, particularly research into the brain’s reward system, provides a strikingly parallel narrative: the biological mechanisms that evolved to promote survival through seeking rewards can also entrap individuals in cycles of craving and dissatisfaction. In this post, we explore the convergence between Buddhist psychology and the neurobiology of craving, highlighting how an understanding of the brain’s reward system deepens our grasp of suffering and points toward practical avenues for liberation.

The default mode network and the dissolution of ego

The experience of a solid, continuous self has long been assumed as an intrinsic feature of consciousness. However, both Buddhist philosophy and contemporary neuroscience challenge this assumption. In Buddhist thought, particularly in Siddhartha Gautama’s teaching of anattā (non-self), the ego is seen as a constructed and ultimately empty phenomenon. Recent findings in neuroscience, especially regarding the default mode network (DMN), lend empirical support to this view. In this post, we explore the relationship between the DMN, the sense of self, and the dissolution of ego, illustrating the remarkable convergence between ancient Buddhist insights and modern brain research.

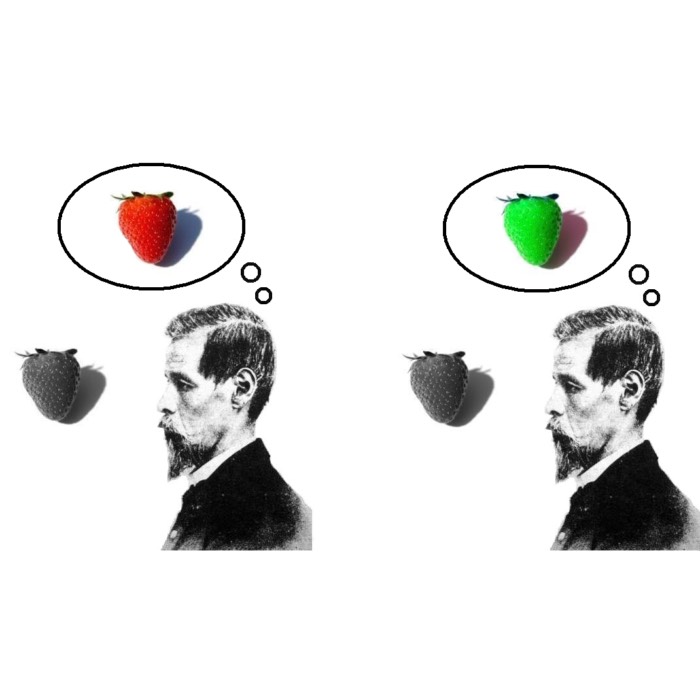

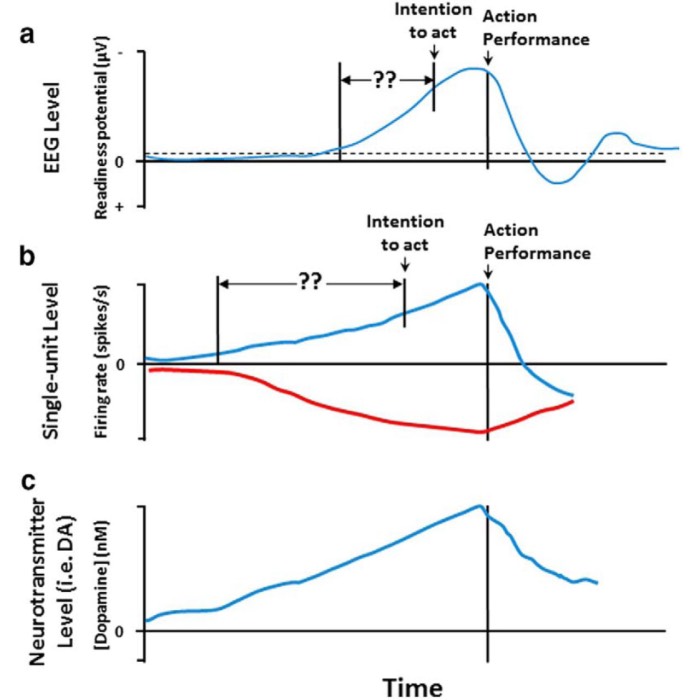

The illusion of free will and Buddhist ethics

The question of free will has occupied Western philosophy for millennia, with debates oscillating between determinism, compatibilism, and libertarian notions of human agency. In recent decades, neuroscience has added a new dimension to the discussion, providing experimental data that challenges the idea of conscious, autonomous decision-making. In a parallel but historically independent development, Buddhist thought, particularly in its earliest formulations by Siddhartha Gautama, has long denied the existence of a permanent self (atman) and has articulated an ethical system based not on absolute agency but on conditioned volition (cetana). In this post, we examine how contemporary neuroscientific critiques of free will resonate with Buddhist insights and how Buddhist ethics provides a coherent and practical framework that transcends the metaphysical dilemma of free will.

How sustained meditation practice alters brain structure and function

Buddhist traditions have long emphasized the transformative power of meditation, describing it as a tool not only for achieving insight into the nature of reality but also for cultivating emotional resilience, ethical behavior, and cognitive clarity. Historically, these claims were grounded in phenomenological reports and philosophical elaborations. In recent decades, however, neuroscience has provided a growing body of empirical evidence suggesting that meditation indeed alters the brain’s structure and function. In this post, we explore the findings that link sustained meditation practice to neuroplastic changes, the underlying mechanisms involved, and the broader implications for understanding the mind-brain relationship.

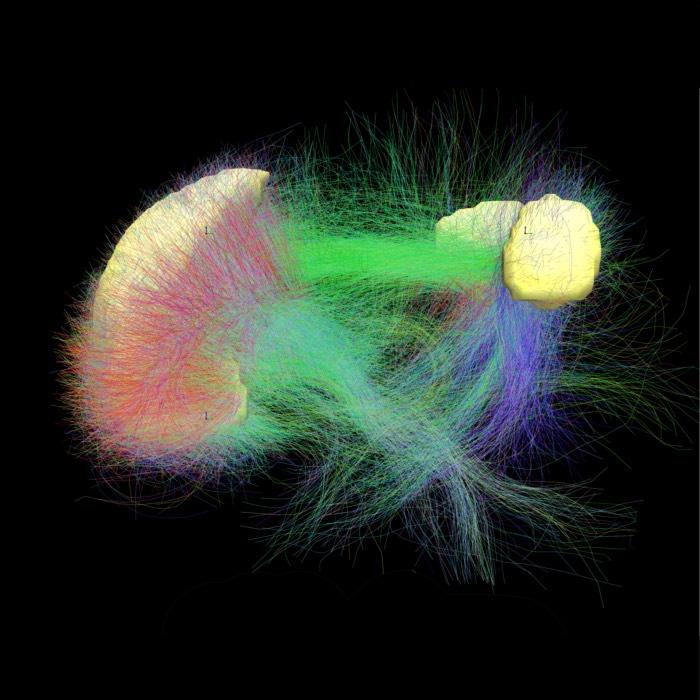

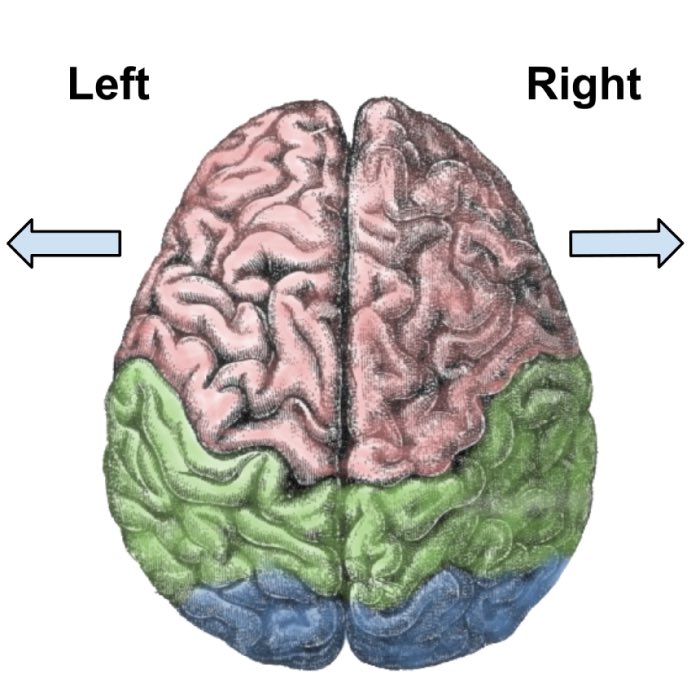

Anattā and neuroscience: questioning the self through split-brain research

In his 2024 book Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung (The Philosophy of the Buddha - An Introduction), philosopher Sebastian Gäb devotes an insightful chapter to the interface between Buddhist philosophy and contemporary neuroscience. One of the central themes of this chapter is how findings from split-brain research can be read as empirical parallels to the early Buddhist doctrine of anattā. Gäb discusses how the surgical separation of the brain’s hemispheres in certain epileptic patients creates conditions in which our conventional idea of a unified self becomes untenable. This uncovers something that Buddhist thinkers, particularly Siddhartha Gautama, had already suggested long ago: that the self is not a unified, inner subject, but a narrative construct arising from dynamic processes. In this post, we briefly explore these connections between Buddhist philosophy and neuroscience in more detail.

The first modern encounters between the West and Buddhism: Colonialism, rediscovery, and reform

The colonial encounter between Western powers and Buddhist societies during the 19th and 20th centuries profoundly reshaped the trajectory of Buddhism. As European empires expanded across Asia, they disrupted traditional Buddhist institutions through economic exploitation, ideological subjugation, and missionary activity. Yet, paradoxically, colonialism also sparked a rediscovery of Buddhism, with Western scholars and archaeologists uncovering ancient texts, monuments, and histories that had long been neglected. This dual dynamic of suppression and revival forced Buddhist communities to adapt creatively, blending traditional teachings with modern ideas of rationalism, nationalism, and scientific inquiry. In this post, we explore how colonialism acted as both a destabilizing force and a catalyst for Buddhist reform, examining the ways in which Buddhist leaders and communities resisted, reinterpreted, and globalized their traditions in response to the pressures of empire.

Barlaam and Josaphat: How Siddhartha became a Christian saint

It is one of the more remarkable ironies of religious history that Siddhartha Gautama was venerated for centuries in Christian Europe as a Christian saint. Under the names Barlaam and Josaphat, the narrative of the Buddha’s life was translated, adapted, and ultimately canonized within Christian hagiography. These figures were widely celebrated throughout medieval Christendom, with their feast day even appearing in the Roman Catholic Martyrology. This post traces the long and surprising transmission of this narrative from its Indian Buddhist origins to its Christianized form in Europe. In doing so, we uncover a fascinating story of cultural adaptation, textual migration, and religious transformation that complicates any clear boundary between East and West, or between Buddhism and Christianity.