Weekend Stories

I enjoy going exploring on weekends (mostly). Here is a collection of stories and photos I gather along the way. All posts are CC BY-NC-SA licensed unless otherwise stated. Feel free to share, remix, and adapt the content as long as you give appropriate credit and distribute your contributions under the same license.

diary · tags · RSS · Mastodon · flickr · simple view · grid view · page 2/52

Kloster Steinfeld: A visit to a monastery between history and the present

In June 2025, a lab retreat brought us to Kloster Steinfeld in the Eifel. Chosen for practical reasons rather than religious ones, the monastery revealed itself as a place suspended between monastic architecture and contemporary use. Basilica, cloister, and garden coexist with seminar rooms and guest housing, quietly exposing the tension between Christian permanence and functional transformation. In this post, I’d like to reflect, in the wake of my earlier post series on both Christianity and Buddhism, on how Kloster Steinfeld embodies Christianity’s shift from theological authority to cultural repurposing.

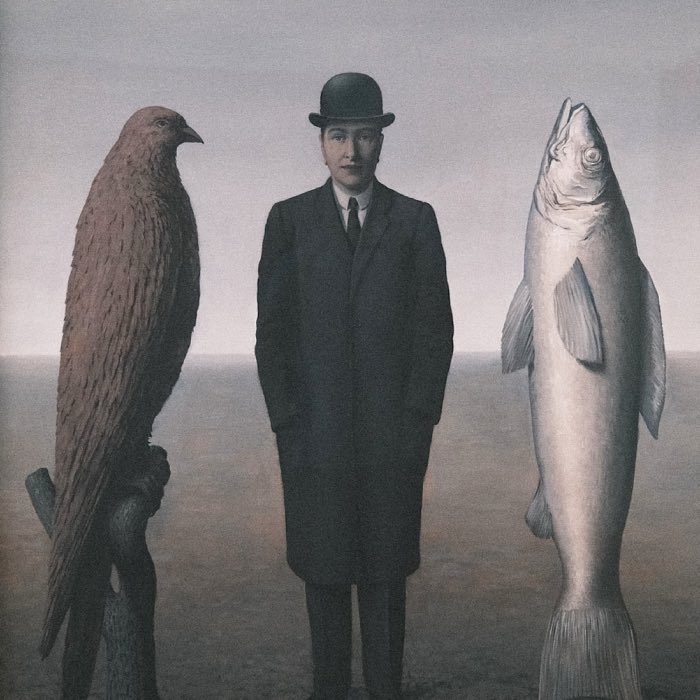

Meeting modern art in the Ruhr Area: A visit to the Folkwang Museum

In May this year, we spent a day in my hometown and we used the opportunity to visit Museum Folkwang nearby. The museum sits right in the center of Essen and, thus, within the former industrial area of the Ruhr region. Even though one might not expect a museum of modern art to be so important in a formerly industrial region like the Ruhr, the Folkwang Museum is an outstanding example of how art and culture can flourish even in such contexts. The museum actually has a long history that is closely linked to the development of the Ruhr region, but also to modern art. In this post, I recap some of the highlights of our visit and illuminate the museum’s historical and cultural background.

A compact classic: My time with the Fujifilm XF10

After my brief detour with the Ricoh GR IIIx, I found myself falling into another corner of online camera hype: the Fujifilm XF10. It is a charming and capable little camera with authentic Fuji colors and a uniquely compact form. But in the end it simply did not align with my personal taste the way the X100VI does. Here are my thoughts on it.

A few thoughts on the Ricoh GR IIIx…and why I returned it

In my quest to fix the unsatisfactory iPhone camera experience, I started thinking about alternative ways to always have a ‘real’ camera with me. My Fujifilm X100VI is compact for what it is, but I still do not carry it everywhere, so that I miss a lot of small everyday moments I would have loved to capture. This is how I ended up trying the Ricoh GR IIIx – for a few days. Here are my brief thoughts on it.

Finally found a solution for iOS’s overprocessed photos

For years I have been dissatisfied with the default iOS Camera app because its computational photography pipeline produces overprocessed, lifeless images. Recently I discovered an alternative app called No Fusion that disables Apple’s multi-frame Deep Fusion processing, yielding consistent, natural-looking photos that better capture the mood and authenticity I seek. In this post, I compare images from the default app, No Fusion, and my Fujifilm X100VI to illustrate the differences.

Zen and Japanese militarism: Complicity and ethical failure

Zen Buddhism is often celebrated for its teachings on mindfulness, compassion, and inner peace, yet its historical entanglement with Japanese militarism reveals a complex and troubling dimension of its past. During the early 20th century, Zen institutions in Japan not only failed to oppose the rise of imperial aggression but, in many cases, actively supported it. In this post, we examine how Zen teachings were reinterpreted and co-opted to align with nationalist and militarist ideologies, exploring the cultural, philosophical, and institutional dynamics that allowed this alignment to occur. By confronting this history, we aim to better understand the challenges of maintaining ethical integrity within spiritual traditions when faced with political and social pressures.

Vegetarianism and Buddhism: Ethics, compassion, and practice

The relationship between Buddhism and vegetarianism reflects a deep ethical inquiry into the nature of compassion, non-violence, and mindful living. Rooted in the First Precept of avoiding harm to sentient beings, the practice of abstaining from meat has been embraced by many Buddhist traditions as an expression of loving-kindness and respect for life. However, the approach to dietary ethics varies widely across Buddhist cultures, shaped by historical, monastic, and regional contexts. In this post, we explore the philosophical foundations, scriptural interpretations, and cultural practices surrounding vegetarianism in Buddhism, highlighting how this ethical choice aligns with the broader principles of the Dharma while accommodating diverse circumstances and perspectives.

Engaged Buddhism: Compassion in action

Engaged Buddhism represents a dynamic movement that bridges traditional Buddhist teachings with the pressing social, political, and environmental challenges of the modern world. Rooted in principles of compassion, mindfulness, and interdependence, it calls for the integration of inner transformation with outward action. Coined by Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh during the Vietnam War, Engaged Buddhism emphasizes that spiritual practice cannot be separated from the realities of suffering in society. In this post, we explore the origins, principles, and practices of Engaged Buddhism, highlighting how it inspires individuals and communities to respond to injustice, violence, and ecological crises with clarity, nonviolence, and compassion.

Buddhism and the environment: Impermanence, compassion, and climate responsibility

The relationship between Buddhism and environmentalism offers a profound perspective on the ecological challenges of our time. Rooted in principles such as interdependence, impermanence, and compassion, Buddhist philosophy provides a framework for understanding humanity’s connection to the natural world and the ethical responsibilities that arise from it. As climate change and environmental degradation intensify suffering for countless beings, Buddhist teachings encourage mindful action, non-harming, and a deep sense of care for all life. In this post, we explore how Buddhist thought and practice intersect with ecological awareness, highlighting the ways in which these ancient teachings inspire meaningful responses to modern environmental crises.

Homosexuality and Buddhism: History, philosophy, and contemporary perspectives

Buddhism has often been perceived as more open or ambiguous toward questions of sexuality than many other religious traditions. In this post, we aim to explore the intersection between homosexuality and Buddhism from both historical and philosophical perspectives. We seek to distinguish between cultural practices within Buddhist societies and the foundational teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama.