The Middle Way: The balance between extremes in Buddhist thought

The concept of the Middle Way (Majjhimā Paṭipadā) represents a central idea in Buddhist philosophy. It refers to a path of moderation that deliberately avoids the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification. Rather than a simple lifestyle recommendation, the Middle Way serves as a philosophical framework with implications for ethics, mental training, and epistemology in various Buddhist traditions. It is presented as the pathway toward the cessation of suffering (nibbāna). In this post, we take a closer look at the Middle Way, its historical roots, and its implications in Buddhist thought.

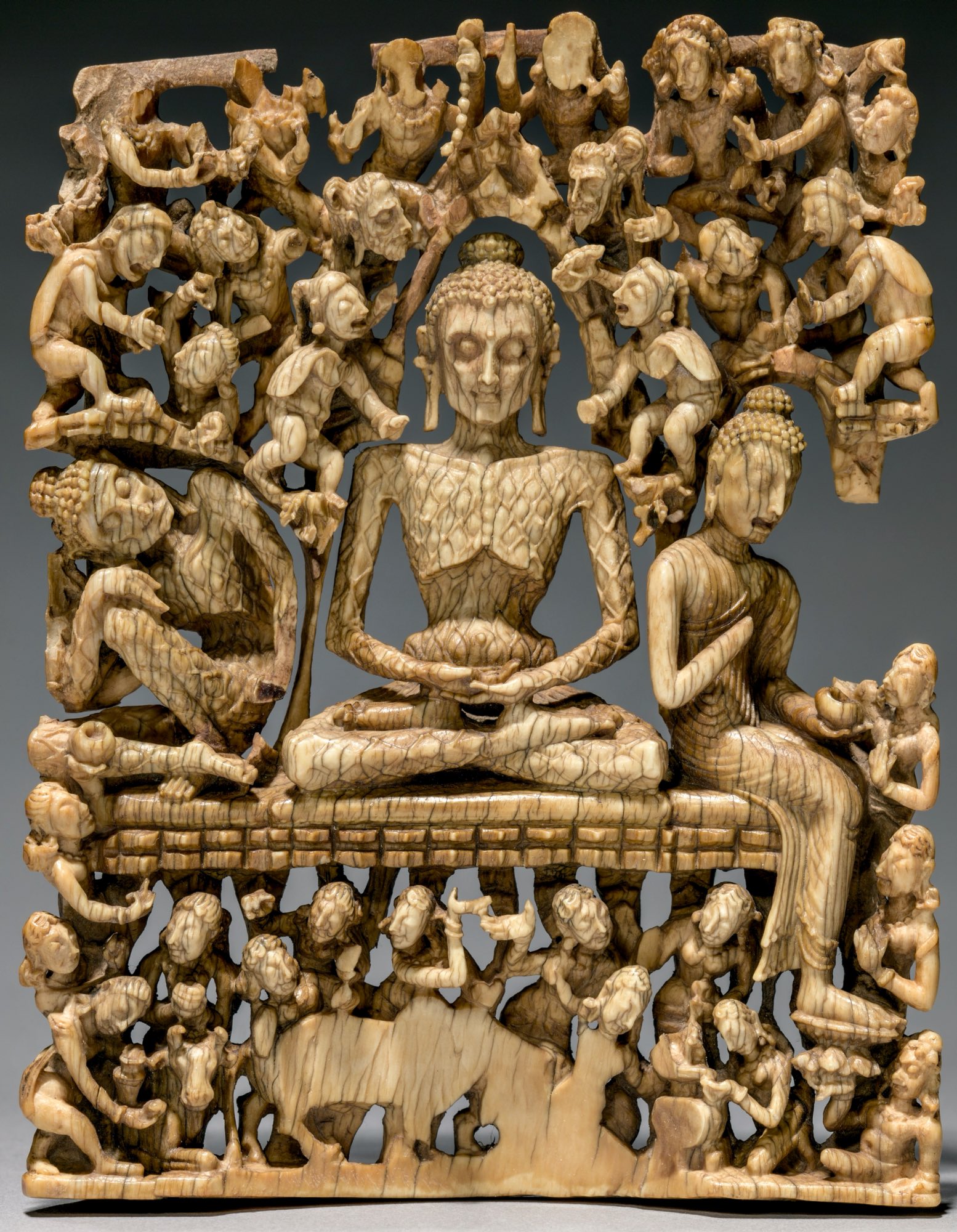

Fasting Buddha, 700 BCE, ivory, India, Kashmir. This intricate ivory carving portrays Siddhartha Gautama at the height of his ascetic phase, a period during which he subjected his body to severe deprivation in the belief that self-mortification might lead to spiritual awakening. Emaciated to the point of skeletal thinness, yet maintaining a composed expression, the figure reflects the intense physical and psychological limits Gautama explored in his quest to understand and transcend suffering. This moment marks a critical turning point: recognizing the futility of such extremes, he would soon abandon asceticism and formulate the principle of the Middle Way — a path that renounces both indulgence and self-denial in favor of balanced insight and sustainable practice. This principle would later become a cornerstone of Buddhist philosophy, guiding practitioners toward a more integrated and holistic approach to spiritual development.Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC0 1.0; modified)

Fasting Buddha, 700 BCE, ivory, India, Kashmir. This intricate ivory carving portrays Siddhartha Gautama at the height of his ascetic phase, a period during which he subjected his body to severe deprivation in the belief that self-mortification might lead to spiritual awakening. Emaciated to the point of skeletal thinness, yet maintaining a composed expression, the figure reflects the intense physical and psychological limits Gautama explored in his quest to understand and transcend suffering. This moment marks a critical turning point: recognizing the futility of such extremes, he would soon abandon asceticism and formulate the principle of the Middle Way — a path that renounces both indulgence and self-denial in favor of balanced insight and sustainable practice. This principle would later become a cornerstone of Buddhist philosophy, guiding practitioners toward a more integrated and holistic approach to spiritual development.Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC0 1.0; modified)

The Middle Way in Siddhartha Gautama’s biography

The principle of the Middle Way is closely associated with a pivotal transition in the early life of Siddhartha Gautama, whose teachings laid the groundwork for what would become Buddhism. According to traditional accounts, Gautama began life in conditions of privilege and luxury, having been born into a royal family. After encountering the realities of aging, illness, and death, he renounced this lifestyle and pursued extreme asceticism in an effort to overcome suffering.

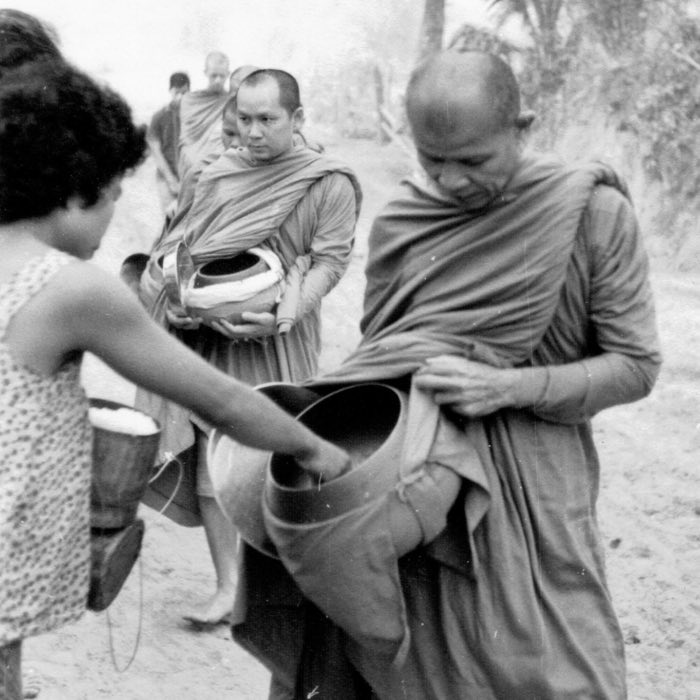

The great fast and the finding of the Middle Way. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In his quest, the young Buddha follows several teachers. For six years, he practices the most severe asceticism, exposing himself to great austerities. Soon he is only skin and bones (right). But his effort brings no benediction. Then the Buddha breaks the fast: he bathes (centre) and eats again (left). He then develops the Middle Way with the help of mindfulness and meditation. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

The great fast and the finding of the Middle Way. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In his quest, the young Buddha follows several teachers. For six years, he practices the most severe asceticism, exposing himself to great austerities. Soon he is only skin and bones (right). But his effort brings no benediction. Then the Buddha breaks the fast: he bathes (centre) and eats again (left). He then develops the Middle Way with the help of mindfulness and meditation. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

Accounts describe how, after years of intense physical austerities, Gautama found that neither indulgence in pleasure nor self-mortification yielded the understanding he was seeking. He shifted to a more moderate approach, resumed eating, and engaged in meditation that culminated in what is referred to in Buddhist sources as his awakening. This biographical narrative is often cited within Buddhist literature to illustrate the Middle Way as an alternative to extreme paths, forming a central element in subsequent Buddhist teachings.

The Middle Way and the Noble Eightfold Path

The Middle Way is conceptually embedded in the Noble Eightfold Path, a core formulation in Buddhist doctrine that outlines eight interrelated domains of ethical conduct, mental discipline, and discernment: Right View, Right Intention, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration. The recurring term “right” in this context implies suitability or optimality, not dogmatic correctness. Each aspect is meant to function as a corrective to behavioral and cognitive extremes.

Rather than treating the Middle Way as a separate principle, the Eightfold Path incorporates it structurally: it serves as a method for maintaining balance across multiple facets of life and practice. For instance, Right Effort calibrates between inertia and overexertion, advocating an alert yet sustainable engagement with one’s mental states. Right Speech exemplifies this balancing act by steering clear of both harmful silence and unchecked verbosity, focusing instead on speech that is measured, timely, and constructive. Right Action, similarly, is situated between moral neglect and ethical dogmatism.

Viewed in this way, the Eightfold Path is not simply a moral or meditative regimen, but a systematic expression of the Middle Way principle applied across existential, practical, and psychological dimensions. It channels moderation not as compromise, but as a strategic method for stabilizing internal and external conditions in pursuit of liberation.

The Middle Way in Buddhist philosophy

The philosophical interpretation of the Middle Way takes on a particularly sophisticated form in the work of Nāgārjuna, an Indian thinker widely regarded as the intellectual founder of the Madhyamaka school within Mahāyāna Buddhism. Nāgārjuna reframed the Middle Way not merely as a behavioral ethic but as a logical and ontological principle aimed at resolving deep conceptual errors in metaphysical thought. He challenged two enduring positions within Indian philosophical discourse: eternalism, the belief in fixed, independently existing essences; and nihilism, the assertion that nothing exists in any real or meaningful way.

Against these poles, Nāgārjuna developed the doctrine of śūnyatā (emptiness), a principle which asserts that all phenomena are empty of inherent existence and come into being only through dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda). This move reframes ontology itself: rather than debating whether something “truly exists” or “does not exist,” the Madhyamaka position suggests that such binaries are themselves misframed. For Nāgārjuna, to exist independently is incoherent, and to deny existence altogether is nihilistic. He summarizes this position strikingly in the opening verse of his Mūla-Madhyamaka-Kārikā (MMK 1.1):

Nowhere and never can you find things that have arisen

- from themselves

- from others

- from themselves and others together

- neither from themselves nor from others

This verse negates all conceivable modes of origination — self-causation, external causation, joint causation, and causation from no cause — thus undermining the very logic of intrinsic existence. Nāgārjuna is not denying the occurrence of phenomena but challenging the ontological assumptions we impose on them. By deconstructing these categories, he points the reader to a mode of understanding grounded in dependent origination and the rejection of absolutist metaphysics. The Middle Way, in this context, is a rigorous philosophical practice: it dismantles extremes not by affirming a new doctrine, but by exposing the incoherence in all attempts to ground reality in essentialist terms. What remains is a middle position: phenomena exist conventionally, as relational events shaped by causal conditions, but lack any intrinsic, self-sufficient essence.

By recasting existence in terms of relational dependence, Nāgārjuna’s Middle Way philosophy attempts to dismantle the foundational assumptions that give rise to reification and metaphysical speculation. It does not present a metaphysical system in the traditional sense, but rather serves as a method of deconstructing conceptual extremes. In this respect, the Middle Way functions as a critical tool — a kind of philosophical therapy aimed at releasing the mind from rigid dualisms and the suffering that arises from clinging to them.

The Middle Way in meditation theory

In discussions of meditation, Buddhist texts describe the Middle Way as a balance between striving and relaxation. Traditions emphasize that excessive effort can lead to mental agitation, while insufficient engagement results in distraction or dullness. The refined states of concentration (jhāna) mentioned in early texts are presented as outcomes of sustained mental equilibrium rather than forceful suppression of thought.

The balancing of emotional and cognitive states is also emphasized. Practitioners are advised to monitor and adjust factors such as excitement or lethargy to maintain steady awareness. This process is associated with the cultivation of equanimity, an emotional stability characterized by non-reactivity to pleasant or unpleasant experiences.

The Middle Way in ethical and social contexts

Buddhist literature extends the Middle Way beyond the monastic sphere into the domain of everyday conduct, where it functions as a framework for navigating complex ethical terrains. Rather than promoting rigid commandments, it emphasizes practical discernment — encouraging individuals to find a sustainable and socially integrated balance in areas such as generosity, speech, consumption, and personal discipline. This application reflects a nuanced view of ethics not as rule-following but as situationally aware responsiveness to conditions.

The avoidance of extreme asceticism is often portrayed not only as a rejection of physical self-denial, but as a safeguard against the psychological and social dangers of withdrawal and moral elitism. Similarly, warnings against indulgence go beyond moralizing, highlighting how attachment to sensory gratification tends to foster compulsive behavior, dissatisfaction, and dependence. The Middle Way thus provides a model for ethical living that is psychologically stable, socially engaged, and internally consistent.

In many Buddhist traditions, this ethos is extended to lay communities, where householders are encouraged to embody moderation in family responsibilities, economic participation, and civic life. By encouraging balance rather than renunciation or indulgence, the Middle Way is framed as a life-affirming ethical orientation — one that does not reject the world, but seeks to live within it skillfully and mindfully. This approach aligns ethical development with the conditions of everyday life, making it a continuous practice of relational attunement and reflection.

Conclusion

The Middle Way, as developed in Buddhist thought, encapsulates a comprehensive framework that avoids extremes across ethical, psychological, and ontological dimensions. It is not a static compromise or an average of opposites, but a methodological principle that counters the limitations of binary thinking — be it between indulgence and asceticism, being and non-being, or emotional overexertion and apathy. From the biographical model of Siddhartha Gautama to the philosophical precision of Nāgārjuna, the Middle Way emerges as a throughline that structures Buddhist approaches to life, mind, and reality.

Critically, what distinguishes the Middle Way from similar concepts in Western philosophy is its deep integration of existential insight with ethical pragmatism. While Western thought has also grappled with avoiding extremes — for instance, Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean or Hegelian dialectics — these often remain abstract or system-bound. In contrast, the Buddhist Middle Way functions as an experiential and relational guide. It is practiced through the Eightfold Path, refined in meditation, and conceptualized in non-essentialist metaphysics.

This integrated character may offer advantages: rather than requiring rigid adherence to principles or endless rational elaboration, the Middle Way prioritizes direct engagement with conditions as they arise. Its practical flexibility allows it to respond to the contingent and impermanent nature of lived experience. In this sense, the Middle Way does not merely advocate moderation, but opens a space in which freedom becomes possible — a freedom not grounded in ideological certainty, but in the relinquishment of extremes and the cultivation of discernment. As such, it remains one of the most distinctive and philosophically rich contributions of Buddhist thought.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments