The role of kōans in Zen

Kōan practice is one of the most distinctive features of Zen Buddhism, particularly within the Rinzai tradition. Often misunderstood or romanticized as mysterious riddles or paradoxes, kōans are in fact a rigorous and deeply structured form of meditative inquiry. Their purpose is not to test logic, nor to offer cryptic knowledge, but to catalyze a break from conceptual thinking and provoke a direct encounter with reality. In this sense, they are not puzzles to be solved but catalysts for awakening.

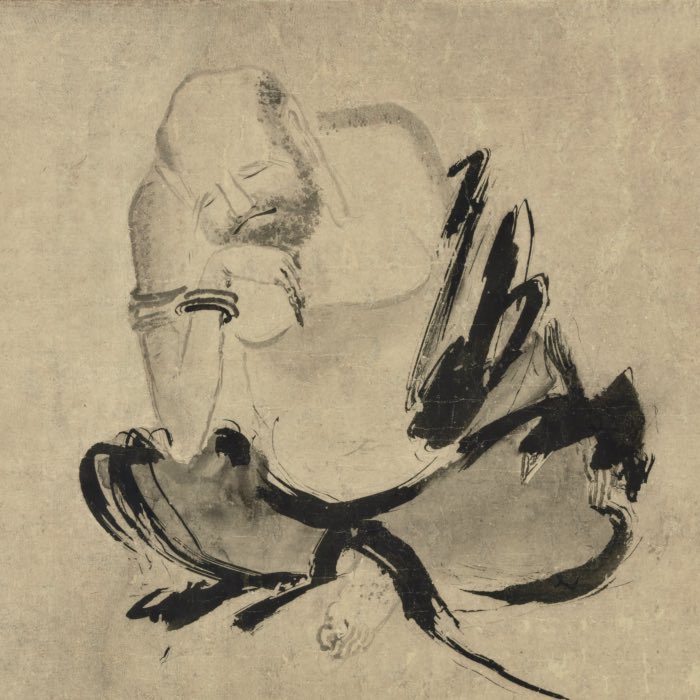

A dog shouting “Mu!”, interpreted by DALL•E 2. The word “Mu” (無) is a Japanese term meaning “nothingness” or “non-existence”. In Zen, it is often used in the context of a famous kōan attributed to the Chinese master Zhaozhou Congshen (Japanese: Joshu Jūshin), who was asked whether a dog has Buddha-nature. His response was simply “Mu”, which has been interpreted as a negation of dualistic thinking and an invitation to explore the nature of existence beyond conceptual categories.

What is a kōan?

The term “kōan” (公案; Chinese: gōngàn) originally referred to legal precedents or public records in Chinese jurisprudence. In the context of Zen, it came to denote recorded sayings or encounters between Zen masters and disciples, often highlighting a moment of sudden insight or non-conceptual understanding. These cases were preserved and transmitted not as teachings to be analyzed, but as living encounters to be entered.

Kōans often appear illogical, humorous, or confrontational. Famous examples include:

- “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

- “Does a dog have Buddha-nature?” — “Mu!”

- “What was your original face before your parents were born?”

Such questions are not intended for discursive reasoning. They are designed to short-circuit habitual patterns of thought and bring the practitioner face-to-face with the limits of conceptual mind.

The function of kōans in practice

Kōans are not standalone anecdotes; they are used in the context of intense meditation and dialogue with a teacher. The practitioner is given a kōan and asked to “present” their understanding — not through intellectual explanation, but through a response that demonstrates direct realization. This might be a gesture, a word, a silence, or a physical act. The teacher evaluates whether the student’s response emerges from genuine insight or conceptual imitation.

The function of kōans is manifold:

- Disruption: Kōans destabilize the ego’s reliance on logic, language, and fixed identity.

- Mirror: They reflect the practitioner’s current state of mind, often revealing attachment, clinging, or pretense.

- Catalyst: When engaged with deeply, a kōan can provoke a sudden shift — a glimpse into the non-dual nature of reality.

Kōan practice and Zen epistemology

In our earlier discussion of Zen epistemology, we emphasized the primacy of direct, non-conceptual knowing over abstract cognition. Kōans are tools precisely for this shift in epistemic mode. They block the way of ordinary understanding, forcing the practitioner into a liminal space where habitual categories fall apart. In that space, clarity may dawn, not as a new idea, but as an unmediated seeing.

This process resembles a kind of epistemic alchemy: reason reaches its limits, and in that collapse, a new mode of knowing can emerge. By epistemic alchemy, we mean a radical transformation in how understanding takes place — not a mere acquisition of knowledge, but a reorientation of perception itself. Kōans do not offer answers to be grasped, but conditions in which insight may arise. The point is not to “solve” the kōan, but to allow it to work on the practitioner — to disorient, provoke, and ultimately reveal what lies beyond conceptual mind.

Kōans in the Zen traditions

While both major schools of Zen in Japan, Sōtō and Rinzai, preserve kōan literature, their usage differs significantly:

- Rinzai Zen emphasizes kōan study as central to its training. Students progress through a series of kōans under the close guidance of a master, often accompanied by strict meditation regimes.

- Sōtō Zen, especially following the teachings of Dōgen, does not focus on kōan introspection in the same structured way. Instead, kōans are used more as teaching stories or poetic expressions within the broader context of “just sitting” (shikantaza).

Despite these differences, both traditions affirm the transformative potential of kōans. Their function is not to entertain or obscure, but to invite the practitioner beyond duality, into the immediacy of suchness.

Famous kōan collections

Over the centuries, many collections of kōans have been compiled. Some of the most notable include:

- The Blue Cliff Record (Chinese: Bi-Yan-Lu, Japanse: Hekiganroku): A classic collection of 100 kōans with commentaries, compiled in the 12th century by the Chinese Zen master Yuanwu Keqin.

- The Book of Serenity (Chinese: Congronglu, Japanese: Shoyoroku): A collection of 100 kōans with commentaries, compiled in the 13th century by the Chinese master Hongzhi Zhengjue. It emphasizes the integration of kōan practice with daily life.

- The Gateless Barrier (Chinese: Wumenguan, Japanese: Mumonkan): A collection of 48 kōans compiled by the Chinese master Wumen Huikai in the 13th century. Each kōan is accompanied by a verse and commentary, emphasizing the direct experience of awakening.

- The Shobogenzo: While not a collection of kōans per se, Dōgen’s writings often include kōan-like passages that challenge conventional thinking and invite deep reflection.

A typical kōan

A typical kōan presents itself as a brief, often enigmatic exchange between a Zen master and a student. It might take the form of a question, an answer, a striking action, or even complete silence. Despite their apparent simplicity or absurdity, kōans are meticulously crafted to expose the practitioner’s habitual attachments to language, logic, and dualistic thought.

For instance, consider the well-known kōan:

Master: “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

Here, the practitioner is confronted with an inquiry that evades resolution through analytical reasoning. The mind’s habitual movement toward logical answers leads only to frustration, thereby opening the possibility for a different kind of knowing — direct, immediate, and non-conceptual. Thus, the practitioner is not expected to provide a verbal answer but to embody the question itself, allowing it to penetrate the layers of conceptualization and reveal the immediacy of experience.

Structure of a typical kōan

The classical kōan often consists of four elements:

- The case (本則, honsoku): A brief narrative, dialogue, or question embodying the central challenge.

- The commentary (著語, jakugo): Annotations by later masters that illuminate or deepen the paradox without resolving it.

- The capping phrase (則, soku): A poetic or literary reference that serves as a secondary pointer.

- Supplementary verses (評唱, hyōshō): Verses that evoke the spirit of the kōan in metaphorical or evocative language.

In formal kōan study (particularly within Rinzai Zen), all parts – the case, the commentary, and the verse – are considered integral. The practitioner is expected to engage with each aspect deeply, not merely as an intellectual exercise, but as fields for existential inquiry.

Practical advice for approaching a kōan

The proper approach to a kōan is not to “solve” it, as one would a riddle, but to embody it fully. Some guidelines include:

- Absorption rather than analysis: One should allow the kōan to saturate consciousness without attempting to grasp it conceptually.

- Sustained, direct inquiry: Holding the kōan in zazen (seated meditation) without seeking a discursive resolution.

- Openness to paradox: Accepting that the habitual mind may experience confusion, frustration, or even apparent failure — all of which are essential phases of the process.

It is said that the kōan “enters” the practitioner, working internally to dissolve the structures that separate subject and object. True engagement with a kōan leads not to a verbal answer, but to a lived transformation.

The role of the teacher

When a practitioner believes an insight has arisen, they present their understanding to their teacher in an interview setting known as sanzen (参禅) or dokusan (独参). This “presentation” is not a conceptual explanation but a direct expression of realization — it might be a gesture, a cry, a silence, or a simple word.

The teacher evaluates whether the response reflects authentic seeing or whether it remains bound to conceptual frameworks. Rarely is the kōan “passed” on the first attempt; repeated engagement is expected, each meeting further polishing the practitioner’s insight.

Over time, this disciplined interplay between the kōan, the practitioner, and the teacher brings about a profound shift: the collapse of the subject-object dichotomy and a direct realization of non-dual reality.

Conclusion: The living edge of the path

Kōans are not intellectual challenges nor poetic curiosities; they are precision tools forged within the living tradition of Zen to catalyze a radical transformation of mind. As explored, their purpose is threefold: to disrupt conceptual fixation, to mirror the practitioner’s present consciousness, and to ignite a direct, non-conceptual seeing of reality.

Far from isolated anecdotes, kōans form a rigorous curriculum within traditions like Rinzai Zen, requiring disciplined engagement under the guidance of a master. Their structure, consisting of case, commentary, and verse, embodies a complete field of meditative inquiry where every element serves as a pointer beyond conceptual entanglement.

Yet kōans do not bestow enlightenment. They merely prepare the ground, dislodging the barriers that conceal what has always been present: the luminous, ungraspable nature of experience itself. In this sense, kōans do not solve questions; they dissolve the questioner.

To approach a kōan is to step onto the living edge of the path — an edge where all familiar certainties fall away, and what remains is neither attainment nor loss, but the simple, radiant immediacy of thusness (tathatā).

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Der Sprung ins Grenzenlose, Das Koan als Mittel der meditativen Schulung im Zen, 1994, 2. Auflage, Otto Wilhelm Barth Verlag

comments