Dōgen Zenji and his significance for Zen Buddhism

Dōgen Zenji (1200–1253) stands as one of the most profound and transformative figures in Japanese Buddhism. At a time when Buddhism in Japan had become heavily ritualized and often entangled with political power, Dōgen sought to return to the pure, experiential heart of the Buddhist path. Dissatisfied with the formalism he found within the established sects, he traveled to China in search of authentic teaching, eventually receiving Dharma transmission from the esteemed Chán master Rujing. Upon his return, Dōgen established a new foundation for Zen practice in Japan, centered around ‘just sitting’ (shikantaza) and the inseparability of practice and realization.

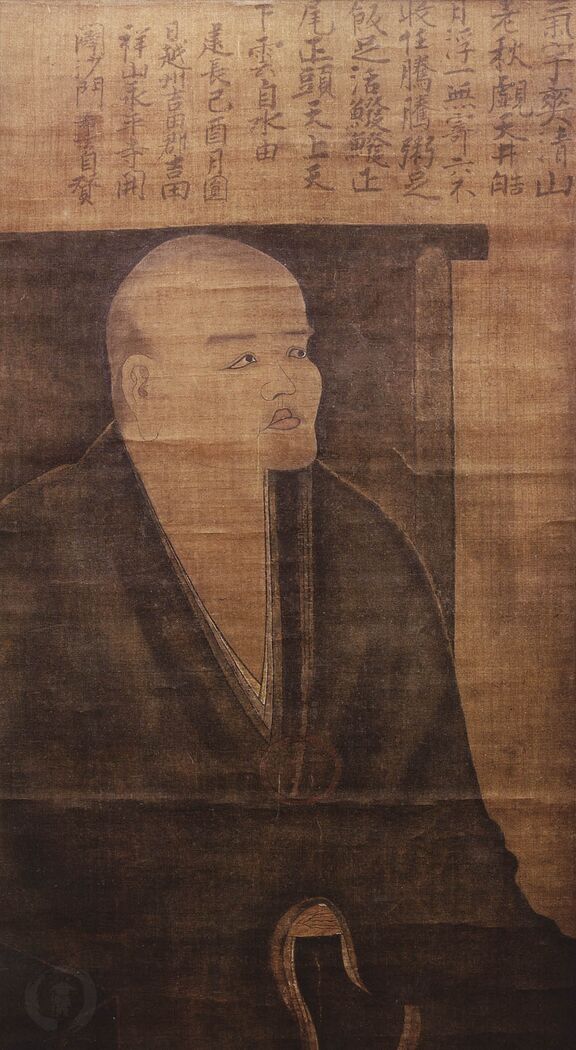

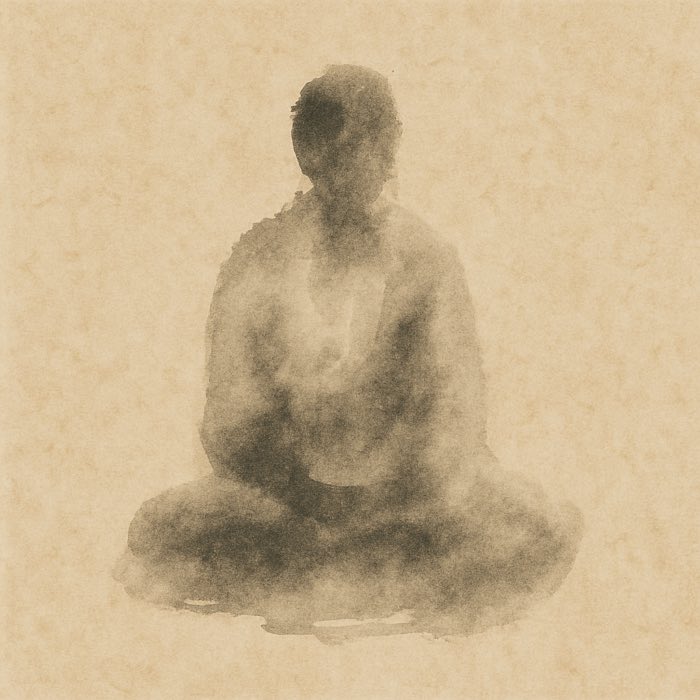

Dōgen watching the moon, Hōkyō-ji, Fukui prefecture, Japan, ca. 1250. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The significance of Dōgen’s life and teachings for Zen Buddhism cannot be overstated. He introduced a deeply philosophical and existential dimension to Zen, exploring the nature of time, being, and the immediacy of awakening with unmatched subtlety. Through his writings, especially the Shōbōgenzō, Dōgen articulated a vision of Buddhism that emphasizes direct experience, rigorous practice, and the realization that the path and the goal are one and the same. His influence not only shaped the Sōtō Zen tradition but continues to inspire contemporary Buddhist thought and practice worldwide.

The state of buddhism in Japan during Dōgen’s time

During the early Kamakura period, when Dōgen lived, Buddhism in Japan was dominated by a few major schools: the Tendai school, the esoteric Shingon school, and the increasingly popular Pure Land (Jōdo) movements. Tendai Buddhism, centered on Mount Hiei, maintained considerable influence, intertwining religious authority with aristocratic and political power. It embraced a wide range of practices, from rigorous scholastic study to esoteric rituals, and often incorporated native Shinto elements, leading to a syncretic religious environment.

At the same time, Pure Land teachings emphasizing devotion to Amida Buddha and the promise of rebirth in the Western Paradise gained traction, especially among the lay population. Figures like Hōnen and Shinran made Buddhist practice more accessible, emphasizing faith and nembutsu (recitation of Amida’s name) over monastic discipline and scholarly learning.

However, the pervasive integration of Buddhism with worldly power and its increasingly elaborate ritual practices led to widespread concerns about corruption and the loss of authentic spiritual purpose. Many sincere practitioners, like Dōgen, perceived the need for a return to the essence of Buddhist practice: direct realization through disciplined, personal effort rather than dependence on rites, institutions, or external salvation.

Dōgen’s early life and search for true teaching

Dōgen was born in 1200 CE in Kyoto into a noble family connected to the imperial court. His father, reportedly a high-ranking official, and his mother, belonging to the influential Fujiwara clan, placed Dōgen within the upper echelons of Heian-era society. Despite this privileged upbringing, Dōgen’s early life was marked by profound personal loss. His mother passed away when he was just a child, an event that deeply affected him and planted the seed of existential inquiry. According to traditional accounts, witnessing the transient nature of life sparked in Dōgen a lasting awareness of impermanence (anicca), a central theme in Buddhist thought.

At the age of thirteen, Dōgen entered the monastic life at Enryaku-ji, the great Tendai monastery on Mount Hiei, which was then the premier center of Buddhist learning in Japan. While immersed in Tendai teachings, he rigorously studied Buddhist doctrine and engaged in monastic discipline. Yet, over time, he grew increasingly disillusioned with what he perceived as the stagnation of the institution. Scholastic debates and elaborate rituals seemed disconnected from the direct realization of enlightenment that the historical Siddhartha Gautama had embodied.

Seeking answers, Dōgen posed a fundamental question: if all beings inherently possess Buddha-nature, as the sutras declare, why is practice necessary at all? This unresolved doubt propelled his search for a more authentic understanding of Buddhist practice. His encounter with Myōan Eisai’s successor, the Rinzai monk Myōzen, proved pivotal. Eisai had been among the first to introduce Chinese Chán (Zen) teachings to Japan, emphasizing meditation over ritual. Under Myōzen’s guidance, Dōgen was exposed to the spirit of Zen, which valued direct experience over intellectualization. Yet even here, he felt something was missing, leading to his decision to seek the true Dharma at its source: the great Chán monasteries of China.

Journey to China (1223-1227)

In 1223, driven by a profound determination to uncover the authentic Dharma, Dōgen set sail for China alongside his teacher Myōzen. Dōgen believed that true understanding could only be achieved through direct contact with the flourishing Chán (Zen) communities in China, where the tradition traced its unbroken lineage back to the Buddha himself. His journey was arduous and fraught with difficulties: maritime travel in the Kamakura period was perilous, and adapting to the foreign land’s language, customs, and monastic culture presented additional challenges.

Upon arrival, Dōgen visited several prominent monasteries in the region, engaging with various Chán masters. However, much like his earlier experiences in Japan, he often found these communities mired in ritualistic practices or formalities that seemed disconnected from the heart of Zen. Nevertheless, these initial experiences deepened his conviction that true practice must go beyond external forms.

Dōgen’s perseverance bore fruit when he encountered Tiantong Rujing, a master at Mount Tiantong’s Jingde Monastery. Under Rujing’s strict and insightful guidance, Dōgen immersed himself in intensive zazen practice. It was during a legendary moment, when Rujing reprimanded a monk for sleeping during meditation and emphasized “dropping off body and mind” (shinjin datsuraku), that Dōgen experienced a profound awakening. This realization dissolved his remaining doubts: enlightenment was not something to be attained externally but was inherent and actualized through wholehearted, undistracted practice.

Recognizing Dōgen’s deep insight, Rujing formally transmitted the Dharma to him, conferring upon him the responsibility to carry the authentic teaching forward. In 1227, following his transmission, Rujing instructed Dōgen to return to Japan and share the true spirit of Chán. Thus, Dōgen embarked on the journey home, carrying not only new teachings but a revolutionary vision of Buddhist practice that would reshape the spiritual landscape of his homeland.

Return to Japan and establishing a new form of Zen (1227 onward)

Upon returning to Japan in 1227, Dōgen initially sought to integrate his newfound understanding of Zen within the Tendai establishment. He hoped to inspire reform by encouraging a return to sincere practice and direct realization, as opposed to scholasticism and ritualism. However, his radical emphasis on meditation and personal awakening, which downplayed elaborate ceremonies and hierarchical structures, quickly led to tensions with the conservative monastic authorities.

Facing resistance and conflict, Dōgen made the critical decision to distance himself from the entrenched religious centers. He chose instead to build a new foundation for Zen, independent of the prevailing sects. In 1233, Dōgen founded Kōshōhōrin-ji in Uji, near Kyoto. Here, he established a community centered on rigorous zazen practice, monastic discipline, and the everyday embodiment of the Dharma. Kōshōhōrin-ji became Japan’s first monastery explicitly dedicated to Zen practice as Dōgen envisioned it.

Later, seeking an even more secluded and conducive environment for training, Dōgen relocated his community to the remote mountains of Echizen Province. In 1244, he founded Eihei-ji, which would become the enduring center of the Sōtō Zen tradition. At Eihei-ji, Dōgen developed a comprehensive monastic code and transmitted his profound teachings, culminating in a living model of Zen practice rooted in daily life, meditation, and the unity of practice and awakening.

Dōgen’s role in Japanese Buddhism of his time

Dōgen’s contribution to Japanese Buddhism during his lifetime was both revolutionary and deeply challenging to the prevailing religious culture. He introduced the practice of shikantaza (“just sitting”), a form of meditation stripped of any goal-oriented striving. For Dōgen, zazen was not a means to an end but the very expression of enlightenment itself.

In addition to meditation, Dōgen placed strong emphasis on monastic discipline, as outlined in his works such as the Eihei Shingi. He advocated for a strict, ethical lifestyle where even the most mundane activities, like eating or cleaning, were opportunities for awakening.

Dōgen also challenged the widespread reliance on devotional practices and elaborate rituals that characterized much of Japanese Buddhism at the time. Instead, he called for a return to direct, personal realization of the Dharma through sincere, embodied practice. His Zen path was neither dependent on external salvation nor on intellectual understanding, but on the deep, lived experience of non-duality in each moment.

Through his teachings and the communities he established, Dōgen positioned his Zen as a revitalization of the authentic Buddhist path — one that emphasized simplicity, awareness, and unwavering dedication to practice.

Dōgen’s broader legacy for Zen Buddhism

The broader legacy of Dōgen extends far beyond his immediate historical context. He infused Zen with a profound philosophical depth that articulated the non-duality of practice and enlightenment. In Dōgen’s view, practice was not preparatory; it was itself the realization of Buddha-nature. This insight distinguished his teaching from interpretations that saw practice as merely a means to achieve a later awakening.

Dōgen’s literary contributions, characterized by poetic and precise language, provided an enduring treasury of Zen thought. Works like Shōbōgenzō (“Treasury of the True Dharma Eye”), Eihei Shingi (monastic regulations), Fukan Zazengi (universal promotion of zazen), and Bendōwa (negotiating the way) encapsulate his vision of Zen as integrated, lived experience.

His influence profoundly shaped the Sōtō Zen tradition, emphasizing silent illumination, wholehearted presence, and the sanctity of everyday actions. Dōgen’s Zen thus continues to inform not only Japanese Buddhism but also global interpretations of Zen and Buddhist practice today.

Central concepts in Dōgen’s teaching

Dōgen’s teachings revolve around several key concepts that together form the foundation of his unique articulation of Zen:

- Practice-enlightenment (shushō ittō): Dōgen emphasized that practice and enlightenment are not separate; the act of practice itself is the manifestation of awakening.

- Uji (Being-Time): In his famous fascicle “Uji,” Dōgen explored the unity of existence and temporality, teaching that every moment fully embodies being and time simultaneously.

- Genjō Kōan (Manifestation of Reality): Dōgen taught that reality manifests itself completely in each phenomenon. To see things as they truly are is to realize the Dharma in every aspect of existence.

- Non-duality and immediacy: Across his teachings, Dōgen stressed the collapse of conceptual dualisms — practice and enlightenment, self and other, being and time — into a single, immediate experience beyond intellectual grasping.

Central writings by Dōgen include:

- Shōbōgenzō (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye): His magnum opus, a collection of profound essays exploring the nature of reality, practice, and enlightenment.

- Eihei Shingi: A detailed monastic code outlining the regulations and daily conduct for Zen practitioners.

- Fukan Zazengi (Universal Promotion of Zazen): A foundational text advocating for the practice of seated meditation.

- Bendōwa (Negotiating the Way): An early and important essay where Dōgen discusses the inseparability of practice and realization.

Dōgen’s death and the continuation of his legacy

Dōgen spent his final years at Eihei-ji, devoting himself to teaching and writing. Despite enduring periods of illness, he continued to refine and transmit his vision of Zen until his death in 1253.

Initially, Dōgen’s influence was limited. His uncompromising emphasis on rigorous practice and philosophical depth made his teachings accessible only to a dedicated few. However, over the centuries, especially during the Edo period, his writings were rediscovered and elevated within the Sōtō school.

Today, Dōgen is recognized not only as the founder of Japanese Sōtō Zen but also as one of the most profound Buddhist philosophers. His legacy endures in the living practices of Zen monasteries, in philosophical discourse, and in the lives of practitioners around the world who continue to “drop off body and mind” and realize the true nature of existence.

The role of Koun Ejō in preserving Dōgen’s teachings

Among Dōgen’s disciples, Koun Ejō (孤雲懐奘, 1198–1280) played a critical role in preserving and transmitting his master’s teachings. Born in 1198, Ejō initially studied Pure Land Buddhism but later turned to Zen in search of a more profound practice. Upon meeting Dōgen, he became one of his closest and most devoted students, ultimately receiving Dharma transmission from him.

Ejō served not only as a practitioner and abbot but also as a careful recorder of Dōgen’s teachings. Many of Dōgen’s sermons and informal talks were transcribed thanks to Ejō’s diligent efforts, later compiled into crucial collections such as the Eihei Kōroku (“Extensive Record of Eihei”). His work ensured that Dōgen’s profound and often challenging teachings were preserved accurately for future generations.

After Dōgen’s death, Ejō succeeded him as the second abbot of Eihei-ji. Though he faced internal conflicts and challenges from within the emerging Sōtō community, Ejō’s loyalty to Dōgen’s vision remained unwavering. His leadership and literary contributions were instrumental in solidifying Dōgen’s legacy and shaping the identity of the Sōtō Zen tradition as it continued to develop in Japan.

Conclusion

Dōgen Zenji stands as a towering figure in the history of Japanese Buddhism, not because he founded a new sect or amassed political influence, but because he fundamentally reoriented the understanding of Buddhist practice and realization. In an era when Buddhism in Japan was often entwined with worldly power, devotionalism, and ritualism, Dōgen offered a radically different vision: that enlightenment is not a distant goal, but is expressed and realized in each moment of wholehearted practice.

His emphasis on shikantaza (“just sitting”) meditation and the inseparability of practice and enlightenment reshaped the spirit of Zen, returning it to a path of immediate, embodied realization. Rather than placing awakening at the end of a linear progression, Dōgen taught that each action, each breath, and each thought was the complete manifestation of the Dharma if engaged with full sincerity.

Philosophically, Dōgen expanded the Zen tradition with profound reflections on time, being, and the nature of reality. His writings, especially the Shōbōgenzō, remain among the most sophisticated and challenging works in the history of Buddhist thought, demonstrating a fusion of existential insight, poetic expression, and rigorous practice.

Although during his lifetime his impact was modest, with his teachings initially confined to a small circle of dedicated disciples, the centuries have revealed the enduring power of his vision. Today, Dōgen is recognized not merely as the founder of the Sōtō Zen school, but as one of the greatest philosophical and spiritual minds in Buddhist history. His call to “drop off body and mind” continues to resonate with those who seek a direct, unmediated encounter with reality, unclouded by conceptualization and dualistic striving.

Dōgen’s life and work remind us that the true path is not found in external forms or future attainments, but in the wholehearted, sincere practice of the present moment — where practice itself is enlightenment.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Dogen Zenji, Shobogenzo – Die Schatzkammer des wahren Dharma-Auges, 4 Bände, 2013, Verlage: Kristkeitz Werner, Übersetzung: Ritsunen Gabriele Linnebach, Gudo Wafu Nishijima, ISBN: 9783921508909

- Dogen Zenji, Unterweisungen zum wahren Buddha-Weg. Shobogenzo Zuimonki (2011), Verlage: Kristkeitz Werner, ISBN: 9783932337680

- Dogen Zenji, Hōkyōki, 2020, Angkor Verlag, Übersetzung: Guido Keller, Taro Yamada, Hidesama Iwamoto, ISBN: 9783943839821

- Dogen Zenji (Autor), Guido Keller (Übersetzer), Taro Yamada (Übersetzer), Eihei Shingi - Regeln für die Zen-Gemeinschaft, 2022, BoD – Books on Demand, ISBN: 9783988040008

- Dogen Zenji (Autor), Guido Keller (Übersetzer), Eihei Kôroku, 2017, Angkor Verlag, ISBN: 9783936018936

- Shohaku Okumura, Die Verwirklichung der Wirklichkeit - «Genjokoan» - der Schlüssel zu Dogen-Zenjis Shobogenzo, 2014, Kristkeitz, ISBN: 9783932337604

comments