Ai-Khanoum: The Greco-Buddhist city in Central Asia

Ai-Khanoum, located at the junction of the Oxus (Amu Darya) and Kokcha rivers in present-day Afghanistan, is one of the most remarkable archaeological sites bridging the Greek and Indian cultural worlds. Often identified with the city of Alexandria Oxiana, its ruins reveal a Hellenistic urban center that flourished far from the Mediterranean core, at the easternmost edge of the Greek world. Discovered in the 20th century, Ai-Khanoum has dramatically reshaped our understanding of how Greek culture interacted with local traditions in Central Asia and beyond.

Map showing the layout of Ai-Khanoum, with the palace complex, gymnasium, and temples. The city was divided into a lower and upper town, with the palace complex located in the lower town. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC 1.0)

More than a colonial outpost, Ai-Khanoum served as a vibrant hub of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and a key link in the chain of Indo-Greek cities that connected the Hellenistic world to India. It represents a unique fusion of Greek architecture, civic life, philosophy, and religious expression with the languages, beliefs, and material cultures of the Iranian and South Asian spheres.

In this post, we explore Ai-Khanoum not only as a city of great historical interest but as a living symbol of cultural hybridity. We aim to show how this city functioned as a microcosm of Greco-Buddhist interaction, illuminating broader patterns of artistic, philosophical, and religious exchange between East and West during the Hellenistic era.

Geographic and strategic location

Ai-Khanoum was strategically situated at the confluence of the Oxus (Amu Darya) and Kokcha rivers, a fertile and defensible location that afforded both economic and military advantages. This riverine position not only supported agriculture and access to water but also placed the city at a vital junction of transregional trade routes. Goods, people, and ideas moved along these arteries, linking the city to both the Hellenistic world to the west and the Indian subcontinent to the southeast.

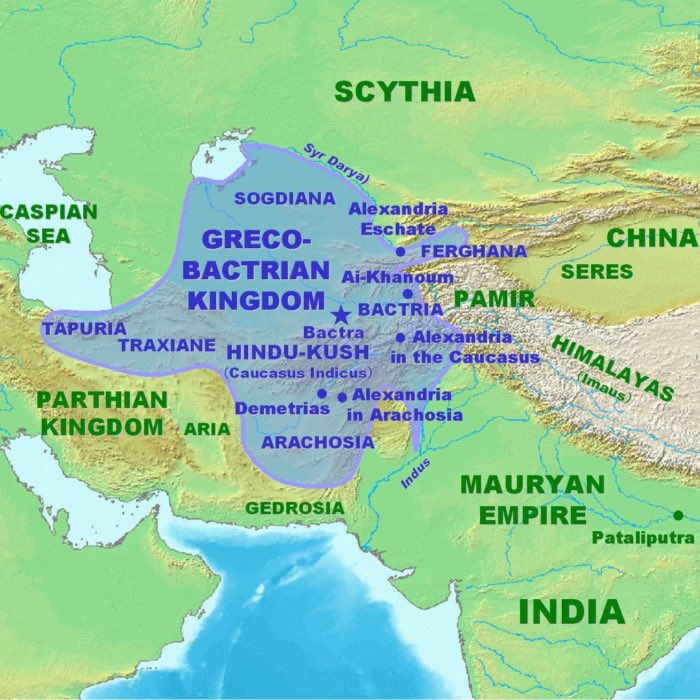

Map of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom at its maximum extent, circa 180 BCE. Important Bactrian cities including Ai-Khanoum are indicated. The kingdom was a significant player in the cultural and commercial exchanges between the Hellenistic world and India. Ai-Khanoum is located in the northeastern part of the kingdom, near the borders with the Iranian plateau and the Indian subcontinent. Today, this area is part of Afghanistan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

As a gateway between Central Asia and India, Ai-Khanoum was perfectly positioned to serve as a staging ground for cultural interaction. Caravans and emissaries traveling the routes of the Silk Roads passed through or interacted with the city, contributing to its cosmopolitan character. Its proximity to the routes running along the Hindu Kush and across Bactria enabled the movement not only of commercial goods like ivory, textiles, and spices, but also of religious ideas, philosophical texts, and artistic techniques.

This intersection of geography and connectivity allowed Ai-Khanoum to become a center not just of economic exchange but of cultural and intellectual synthesis. It embodied the dynamic interaction between Greek and local cultures, creating a shared space where Hellenistic urban ideals could flourish alongside Iranian, Indian, and Central Asian traditions.

Historical background

Ai-Khanoum was likely founded in the aftermath of Alexander the Great’s eastern campaigns in the late 4th century BCE, as part of a broader effort to consolidate Hellenistic presence in newly conquered territories. Though direct evidence linking Alexander himself to the city is inconclusive, the layout and cultural markers strongly suggest it was established by his successors, probably during the reign of Seleucus I or one of his immediate heirs. Many scholars associate the city with “Alexandria Oxiana,” one of several cities named after Alexander, though the precise identification remains debated.

The city grew to prominence under the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, which emerged in the early 3rd century BCE after breaking away from the Seleucid Empire. Under kings such as Diodotus I, who declared independence, and later rulers like Eucratides the Great, Ai-Khanoum became a focal point of Hellenistic culture in Central Asia. The city was a political and administrative center, but also a showcase of Greek urban planning, philosophy, and artistic patronage in a distant and culturally complex landscape.

What makes Ai-Khanoum historically exceptional is not only its origins in the Hellenistic colonial framework, but also its ability to adapt and thrive as a hybrid entity. Rather than serving merely as a transplanted Greek polis, the city reflects a dynamic interaction with local Iranian and Indian traditions, pointing toward a more integrated and reciprocal model of cultural contact.

Ai-Khanoum and the roots of Gandhāran art

Although Ai-Khanoum is not geographically part of Gandhāra and predates the height of Gandhāran Buddhist art, it played an important cultural role in laying the groundwork for later developments. The city represents one of the earliest and most comprehensive examples of Hellenistic influence in Central Asia. Its architectural vocabulary, urban planning, and sculptural forms, including Corinthian columns, propylaea (monumental entrance gateways), and gymnasia, introduced a Greco-Mediterranean visual language that would later resonate in the art of Gandhāra. While the Buddha images characteristic of Gandhāran art emerged centuries later and farther southeast, the presence of Ai-Khanoum and other Greco-Bactrian centers helped foster an artistic and intellectual climate receptive to such syncretism. In this way, Ai-Khanoum may be seen as part of the wider Hellenistic heritage that informed the eventual fusion of Greek and Buddhist iconography.

Urban structure and architecture

Ai-Khanoum’s cityscape reveals a remarkable transplantation of Greek urban ideals into the heart of Central Asia. Archaeological excavations have uncovered a well-organized grid system typical of Hellenistic city planning, complete with a central agora (public square), wide avenues, and zoning that distinguished public, religious, and residential areas. The structured layout exemplifies the Greek polis model, reimagined in a foreign geographical and cultural environment.

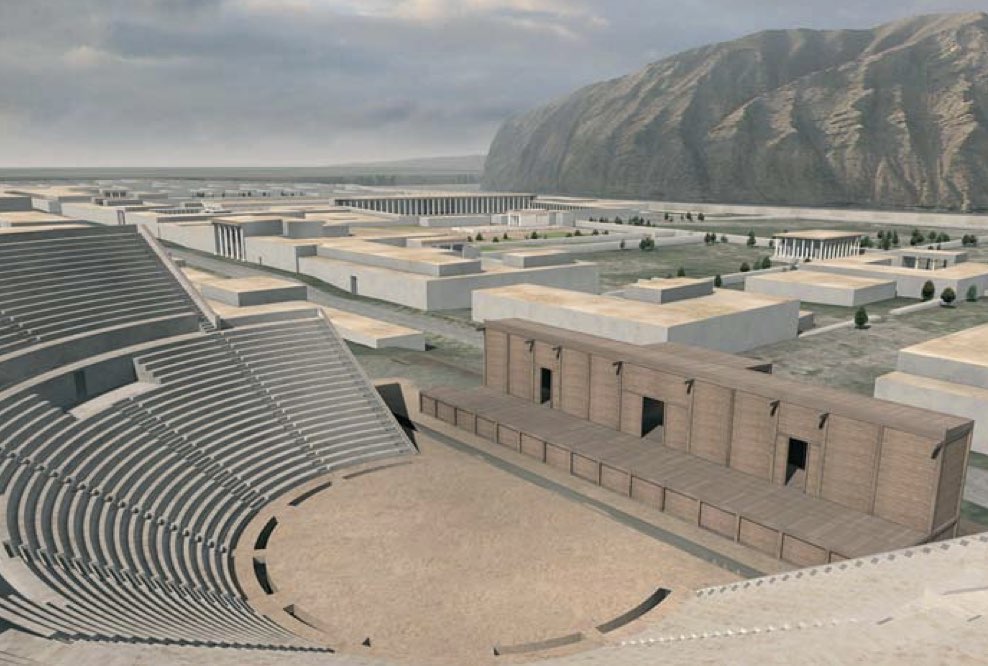

Ai-Khanoum: Restored 3D view of the city, with the northern rampart punctuated by massive towers in the foreground and the Darya-i Pandj river visible to the right. 3D reconstruction by O. Nishizawa (NHK-TAISEI). Source: Figure 1 from: Lecuyot, G. & Nishizawa, O. (2013), Une collaboration franco-japonaise à la restitution 3D de la ville d’Aï Khanoum, HAL open-access archiveꜛ. Used here for educational and critical commentary under fair use provisions. All rights remain with the original rights holders.

Among the city’s most notable structures were a vast palace complex, a large theater, a gymnasium, and several temples. The palace, likely used by Greco-Bactrian rulers, displayed monumental scale and sophistication, including columned courtyards, reception halls, and storerooms. The gymnasium, a central institution of Greek civic life, served as both an educational and athletic center, with its size and architectural detail suggesting the city’s commitment to maintaining Greek civic traditions. The presence of a theater indicates not only an appreciation for drama and performance but also the transplantation of communal cultural life.

Ai-Khanoum: Restored 3D view of the city with, in the foreground, the theater featuring a wooden stage building. In the middle ground, from left to right: the propylaea (monumental entrance gateway) leading to the palace complex, opening onto the main street through a portico with four columns set in antis (i.e., placed between two projecting side walls); at center, the heroon of Kineas (a commemorative shrine dedicated to the city’s legendary founder); and to the right, the ‘royal’ mausoleum with its stone burial chamber. The palace colonnade rises in the background. 3D reconstruction by O. Nishizawa (NHK-TAISEI). Source: Figure 2 from: Lecuyot, G. & Nishizawa, O. (2013), Une collaboration franco-japonaise à la restitution 3D de la ville d’Aï Khanoum, HAL open-access archiveꜛ. Used here for educational and critical commentary under fair use provisions. All rights remain with the original rights holders.

Temples in Ai-Khanoum reflect both Hellenistic and local religious architectural styles. Some followed Greek design with colonnaded facades and classical proportions, while others incorporated elements more typical of Iranian and Central Asian religious architecture, revealing the city’s integrative spirit. The blending of architectural idioms extended to materials as well: while the design was Hellenistic, builders often employed local stone and construction techniques, showing a practical adaptation to the environment.

Ai-Khanoum: Restored 3D view of the central zone of the city. In the foreground, from left to right: the main temple and the propylaea (monumental entrance gateway) leading to the palace. In the background: the palace itself, the heroon of Kineas (a commemorative monument dedicated to the city’s legendary founder), and the ‘royal’ mausoleum with its stone burial chamber. 3D reconstruction by O. Nishizawa (NHK-TAISEI). Source: Figure 5 from: Lecuyot, G. & Nishizawa, O. (2013), Une collaboration franco-japonaise à la restitution 3D de la ville d’Aï Khanoum, HAL open-access archiveꜛ. Used here for educational and critical commentary under fair use provisions. All rights remain with the original rights holders.

Ai-Khanoum’s urban structure is thus a material testament to the city’s cultural hybridity. While overtly Hellenistic in layout and civic ideology, its architecture reveals a responsiveness to local traditions and ecological realities. It stands as a unique example of how Greek urban forms could be both preserved and transformed in a culturally pluralistic setting.

Art, inscriptions, and education

Ai-Khanoum offers some of the most compelling evidence for the cultural synthesis between the Hellenistic world and Central Asia, especially in the realms of art, literacy, and education. Artistic remains from the site display a refined blend of Greek stylistic elements and regional aesthetic traditions. Marble statuary, Corinthian columns, and ornamental friezes clearly follow classical Greek models, but these are often found alongside local motifs and decorative techniques, producing a hybrid artistic language that was both familiar to Greek settlers and accessible to the surrounding populations.

Left: Bronze Heracles statuette, found at Ai Khanoum, 2nd century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Sculpture of an old man, possibly a philosopher, found at Ai Khanoum, 2nd century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

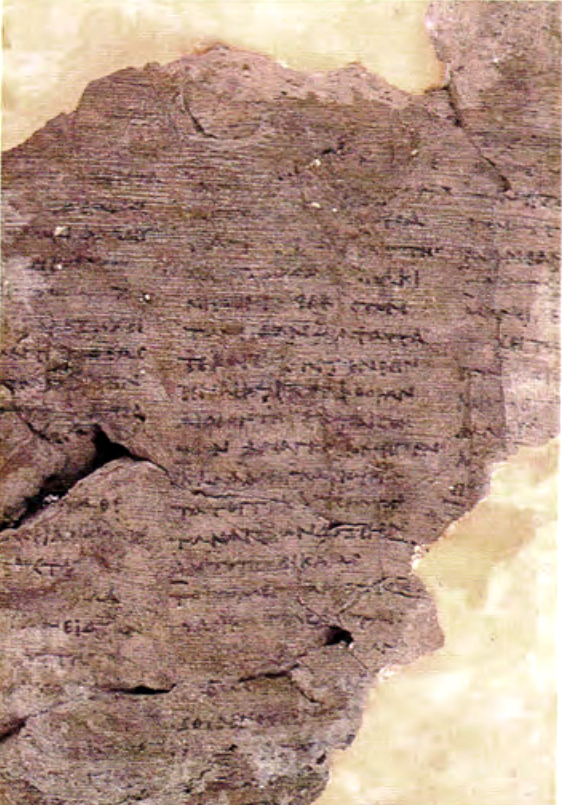

Philosophical papyrus, found in the library of Ai Khanoum. The parchment constituted an unknown theatrical work, most probably a trimetrical tragedy, possibly involving Dionysus, a figure known for traveling to India and the East. On the other hand, the papyrus was a philosophical dialogue discussing the theory of forms of Plato, which some have considered a lost work by Aristotle. It is also possible, conversely, that the text was written by a Greco-Bactrian philosopher in Ai-Khanoum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The city is particularly noteworthy for its inscriptions, many of which were written in Greek and reflect the educational and philosophical culture that flourished in Ai-Khanoum. Among the most famous is a set of moral and philosophical maxims carved onto stone stelae within the gymnasium complex. These inscriptions, derived from the Delphic maxims and other sources of Hellenic ethical thought, suggest that philosophical education was not peripheral but central to civic life in the city. The presence of such texts in public and educational settings underscores the value placed on intellectual cultivation, ethical behavior, and communal identity rooted in Greek traditions.

Portrait of a man, found in the administrative palace of Ai Khanoum. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The gymnasium itself served as more than just a place for physical training. It functioned as an educational institution where young men received instruction in language, rhetoric, music, mathematics, and philosophy, the foundational components of the Greek paideia. Archaeological findings, including scroll fragments and architectural details, support the view that Ai-Khanoum hosted an active intellectual environment, perhaps even a small philosophical community or school.

Corinthian capital, Ai Khanoum, 3rd - 2nd century BCE, limestone. Capitals like the depicted one highlight the blending of Greek architectural styles with local craftsmanship. The intricate floral designs and proportions reflect both Hellenistic aesthetics and regional influences. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Together, the artistic and epigraphic evidence paints a picture of a city deeply invested in preserving and adapting Hellenistic culture. At the same time, the artistic blending and public inscriptions reflect a cultural openness: while Greek in form and intent, the content and context reveal a dialogue with the broader Central Asian world, making Ai-Khanoum a unique center of transregional education and artistic innovation.

Religious and cultural hybridity

The religious life of Ai-Khanoum reflects the city’s status as a crossroads of civilizations. Archaeological evidence reveals the coexistence and interaction of Hellenistic religious forms with local and Eastern cultic traditions. The city featured temples that adhered to classical Greek architectural models, such as columned façades and interior sanctuaries housing statues of Greek gods. These spaces served traditional Hellenistic worship practices, likely honoring deities such as Zeus, Heracles, or local Greco-Iranian syncretic variants.

High-relief of a male figure, Ai Khanoum. Hellenism’s anthropomorphic artistic expression was adapted by the local artisans, who further incorporated regional styles and motifs and adopted it to their own cultural context. This fusion is what later became a hallmark of Greco-Buddhist art. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Yet these temples were not isolated from their context. In Ai-Khanoum and its surrounding region, Eastern religious practices, especially those rooted in Iranian and possibly early Indian traditions, likely coexisted with Greek forms. Architectural features and iconographic elements in some structures suggest hybrid or adapted cult practices. For example, fire altars or ritual spaces may have been integrated into temple precincts, pointing to Zoroastrian or local Bactrian religious influence.

Although direct archaeological evidence for Buddhism in Ai-Khanoum is currently lacking, some scholars have suggested that symbolic influences may have been present by the later phases of the city’s occupation. The city’s proximity to areas where Buddhism was flourishing, its openness to Indian cultural elements, and its role in the broader Greco-Bactrian realm, all support the possibility of indirect Buddhist presence or influence. Given Ai-Khanoum’s integrative character, it is plausible that some Buddhist ideas or symbols entered the city’s ritual and cultural vocabulary, even if not formally institutionalized.

What emerges is a portrait of a city where ritual life was not bound to a single tradition, but instead reflected a fluid and adaptive engagement with multiple religious worldviews. The blending of Greek and local forms in sacred architecture, the possible coexistence of multiple cults, and the willingness to integrate elements across traditions point to a complex and pragmatic approach to religious identity. Ai-Khanoum thus stands as a key example of religious hybridity in the ancient world, where belief systems met, adapted, and reshaped one another in ways that transcended cultural borders.

Decline and legacy

Ai-Khanoum’s vibrant existence came to an abrupt end in the mid-2nd century BCE, likely around 145 BCE, when the city was destroyed, possibly during incursions by nomadic groups such as the Sakas or Yuezhi. While the precise cause remains uncertain, the sudden and violent nature of its abandonment is suggested by archaeological evidence of widespread fire damage and hurried evacuations. The fall of Ai-Khanoum coincided with the broader fragmentation of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and the reshaping of political powers in Central Asia.

For centuries, the city lay forgotten beneath layers of sediment and historical obscurity, until its rediscovery in the 20th century by French archaeologists led by Paul Bernard. Excavations beginning in the 1960s revealed a remarkably well-preserved Hellenistic city, complete with Greek inscriptions, monumental public buildings, and artifacts that confirmed deep cultural fusion. These findings significantly altered the scholarly understanding of Hellenistic influence in the East, revealing not merely a frontier settlement, but a sophisticated cultural center embedded in a rich web of transregional exchange.

Stele with the inscription of Kineas, Ai Khanoum, 2nd century BCE. The inscription reads: “These wise sayings of men of old, The words of famous men, are consecrated At holy Delphi, where Klearchos copied them from carefully To set them up, shining from afar, in the sanctuary of Kineas. As a child, be well behaved; As a young man, self-controlled; In middle age, be just; As an elder, be of good counsel; And when you come to the end, be without grief.” Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Ai-Khanoum has since become emblematic of a broader historical narrative: one in which Greek and Indian, Iranian and Central Asian cultures converged and produced something unique. Even though direct Buddhist elements remain sparse at the site, the city’s artistic, educational, and religious hybridity laid the groundwork for the Greco-Buddhist developments that would flourish in nearby regions like Gandhāra. In this sense, Ai-Khanoum challenges rigid cultural boundaries and encourages a more nuanced view of ancient globalization. Its legacy lies not only in its ruins but in its capacity to shift our understanding of how deeply interconnected the ancient world truly was.

Conclusion

Ai-Khanoum stands as a compelling testament to the cultural fluidity and dynamism of the Hellenistic world. Far from the Greek mainland, this city manifested the architectural, philosophical, and civic ideals of the polis while simultaneously engaging deeply with Iranian and Indian cultural landscapes. Its urban structure, educational life, religious practices, and artistic output all reveal a level of synthesis that challenges conventional narratives of East–West separation.

Rather than a static outpost of Greek culture, Ai-Khanoum functioned as a space of genuine cultural negotiation and mutual adaptation. Its inhabitants — administrators, scholars, artisans, and priests — created new forms of identity that transcended ethnic and religious boundaries. The result was not cultural dilution, but innovation: a reimagined Hellenism forged in dialogue with local traditions.

This city helps reframe how we understand the reach and character of Hellenistic expansion. It invites us to see Greek–Indian and Greek–Iranian interaction not simply as an imposition of Western ideas, but as a shared and evolving process of cultural production. While the Buddhist dimensions of Ai-Khanoum remain speculative, the intellectual and material infrastructure it helped pioneer would later prove fertile ground for the flourishing of Greco-Buddhism in regions like Gandhāra.

Ai-Khanoum also leaves open questions. How deeply did local populations shape the city’s Hellenistic identity? To what extent did its hybrid forms influence later Indo-Greek and Kushan centers? And what does its sudden destruction tell us about the fragility of cultural synthesis in periods of geopolitical upheaval?

As a case study, Ai-Khanoum continues to challenge rigid civilizational boundaries and reminds us that ancient history, like culture itself, is always more interconnected than we imagine.

References and further reading

- Guy Lecuyot, Osamu Nishizawa, NHK, Taisai, CNRS: une collaboration franco-japonaise à la restitution 3D de la ville d’Aï Khanoum en Afghanistan, Virtual Retrospect 2005, Robert Vergnieux, Nov 2005, Biarritz, France. pp.121-124, hal-01763104ꜛ. We use some of the figures from this paper under fair use for purposes of scholarly commentary. All rights remain with the original rights holder.

- Holt, Frank, When Did the Greeks Abandon Ai Khanoum?, 2012, Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia (3): 161–172. OCLC 999046800ꜛ

- Lerner, Jeffrey, Revising the Chronologies of the Hellenistic Colonies of Samarkand-Marakanda (Afrasiab II-III) and Aï Khanoum (Northeastern Afghanistan), 2010, Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia (1): 58–79. OCLC 922503718ꜛ

- Lerner, Jeffrey, A reappraisal of the economic inscriptions and coin finds from Aï Khanoum, 2011, Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia (2): 103–147. OCLC 999031857ꜛ

- Lerner, Jeffrey, Die Studies of Six Greek Baktrian and Indo-Greek Kings, 2018, Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia (9): 236–246, linkꜛ

- Lerner, Jeffrey, Regional study: Baktria – the crossroads of ancient Eurasia”, in Benjamin, Craig (ed.) The Cambridge World History, Vol. 4: A World with States, Empires and Networks 1200 BCE–900 CE, 2015, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 300–324. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139059251.013ꜛ, ISBN 978-1139059251

- Mairs, Rachel, Greek Settler Communities in Central and South Asia, 323 BCE to 10 CE, in Quayson, Ato; Daswani, Girish (eds.). A Companion to Diaspora and Transnationalism, 2013, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 443–454, doi: 10.1002/9781118320792.ch26ꜛ

- Sherwin-White, Susan; Kuhrt, Amélie, From Samarkhand to Sardis: a new approach to the Seleucid Empire, 1993, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520081833

- Bernard, Paul, Aï Khanum on the Oxus: A Hellenistic city in central Asia, 1967, Oxford University Press

- Boardman, J., The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity, 2023, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691252834

- Stoneman, Richard, The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks, 2019, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691154039

- Thomas C. McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, 2001, Allworth, ISBN: 978-1581152036

- Karttunen, Klaus, India and the Hellenistic World, in India and the Hellenistic World: A Bibliographic Introduction, 2017, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120841000

- Tarn, W. .W., The Greeks in Bactria and India, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108009416

comments