Anattā and neuroscience: questioning the self through split-brain research

In his 2024 book Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung (The Philosophy of the Buddha - An Introduction), philosopher Sebastian Gäb devotes an insightful chapter to the interface between Buddhist philosophy and contemporary neuroscience. One of the central themes of this chapter is how findings from split-brain research can be read as empirical parallels to the early Buddhist doctrine of anattā. Gäb discusses how the surgical separation of the brain’s hemispheres in certain epileptic patients creates conditions in which our conventional idea of a unified self becomes untenable. This uncovers something that Buddhist thinkers, particularly Siddhartha Gautama, had already suggested long ago: that the self is not a unified, inner subject, but a narrative construct arising from dynamic processes.

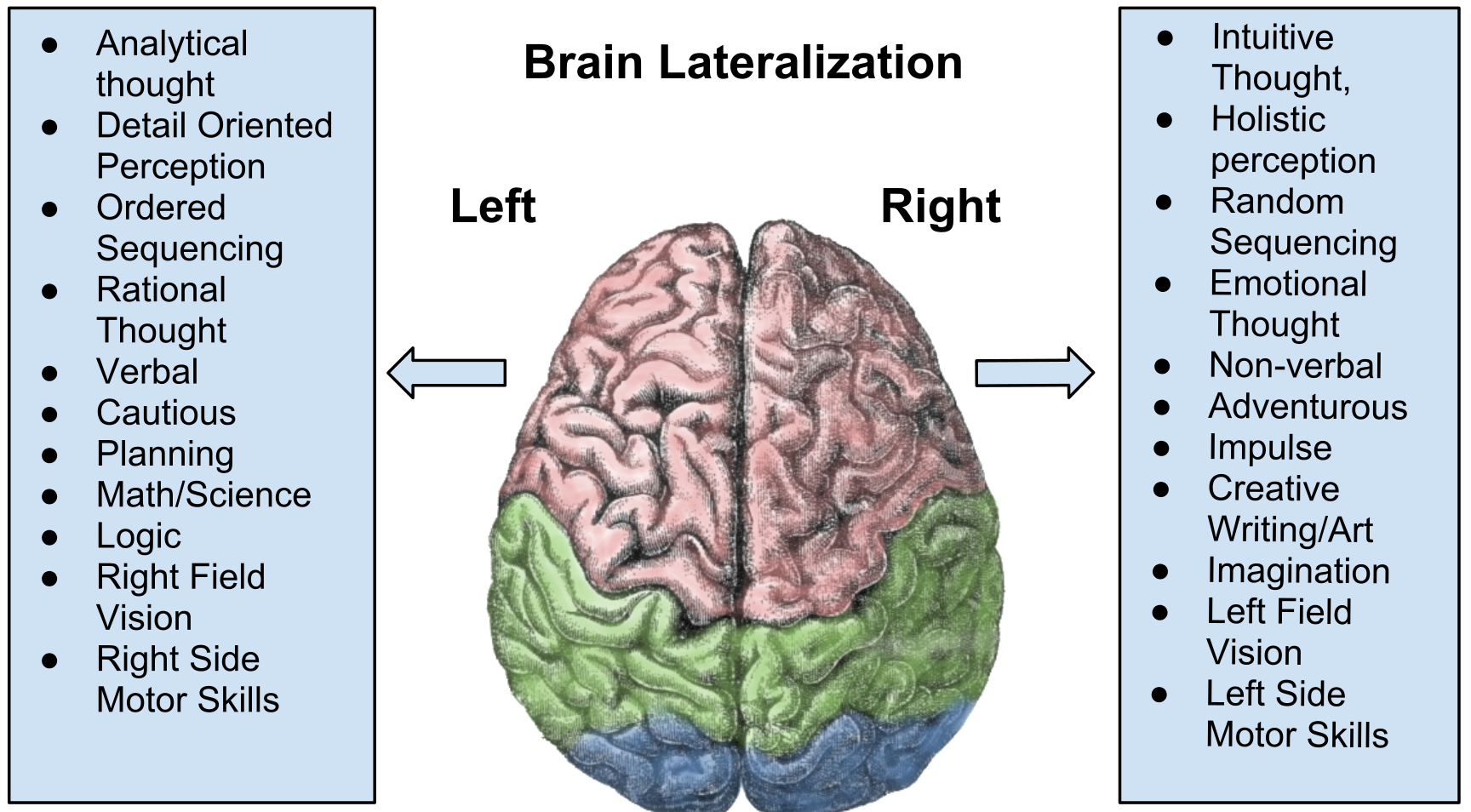

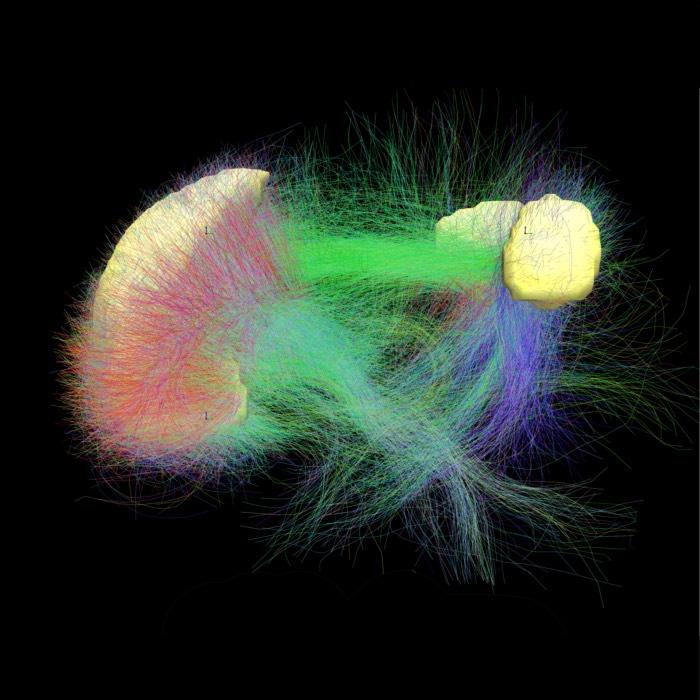

Lateralization of the human brain, which is divided into two hemispheres. The left brain controls functions that have to do with logic and reason, while the right brain controls functions involving creativity and emotion. Note: This type of left-right assignment is highly simplified and does not correspond to the current state of research, which assumes overlapping and interconnected functional systems. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Introduction

One of the most distinctive teachings of early Buddhism is the doctrine of anattā, the claim that there is no permanent, unchanging self or soul (ātman) underlying our experience. This view contrasts sharply with many Western philosophical and religious traditions, which have historically posited a stable, continuous subject or essence. The Buddhist position, as articulated in early sources such as the Saṃyutta Nikāya 22.59 (Anattā-lakkhaṇa Sutta), holds that what we take to be the self is in fact a bundle of impermanent and conditioned processes (khandha or aggregates), none of which qualifies as a true or independent self.

While such metaphysical claims were originally grounded in introspective observation and meditative insight, contemporary neuroscience has, perhaps unexpectedly, begun to raise similar questions about the nature of the self. In particular, split-brain research since the 1960s has provided empirical evidence that challenges the coherence of a unified self. By disrupting the communication between the brain’s hemispheres, these studies reveal the fragility and constructed nature of our sense of self. This article explores how such findings may be interpreted as converging, at least partially, with the Buddhist insight of anattā.

The split-brain phenomenon

In cases of severe epilepsy, some patients have undergone a surgical procedure known as corpus callosotomy, in which the corpus callosum, the bundle of neural fibers connecting the brain’s two hemispheres, is severed. This intervention prevents the spread of seizures across hemispheres and can lead to a substantial reduction in symptoms. Remarkably, most patients appear behaviorally normal in everyday life after the surgery.

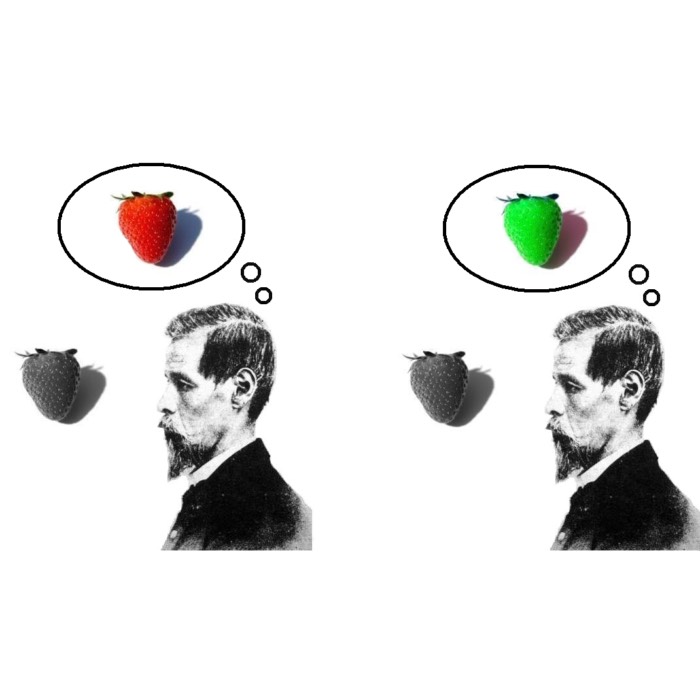

However, under controlled experimental conditions, striking effects emerge. Since each hemisphere controls and receives input from the opposite side of the body, researchers can present visual stimuli to only one hemisphere by limiting input to a single visual field. For instance, if the word “hat” is shown to the left visual field (thus reaching only the right hemisphere), the patient may verbally deny having seen anything, since language production typically resides in the left hemisphere. Yet, if the patient is asked to use their left hand (controlled by the right hemisphere) to pick out an object matching what they saw, they may accurately select a hat.

These experiments suggest that each hemisphere can independently process information and even form intentions. In another case, the right hemisphere was shown the instruction “walk”, and the patient stood up and began to leave the room. When asked why, the left hemisphere, unaware of the instruction, invented a plausible-sounding reason such as “I wanted to get a drink”. Such results rely on the right hemisphere’s limited but demonstrable ability to process simple written commands; more complex linguistic structures are typically beyond its capacity.

What is particularly striking here is not simply that the brain’s hemispheres can act independently, but that each hemisphere appears to have access to distinct streams of consciousness, at least under specific experimental conditions1. The speaking hemisphere, ignorant of what the other half of the brain has perceived or decided, nonetheless constructs a narrative of unified agency. This suggests that our ordinary sense of self as a coherent “I” who sees, decides, and acts may itself be a retrospective, interpretive fiction.

Implications for the concept of self

The split-brain experiments invite a number of philosophical and psychological questions. When a patient says, “I didn’t see anything”, but then correctly selects a hat with their non-dominant hand, what does this imply about the “I”? Which hemisphere, if either, represents the true subject?

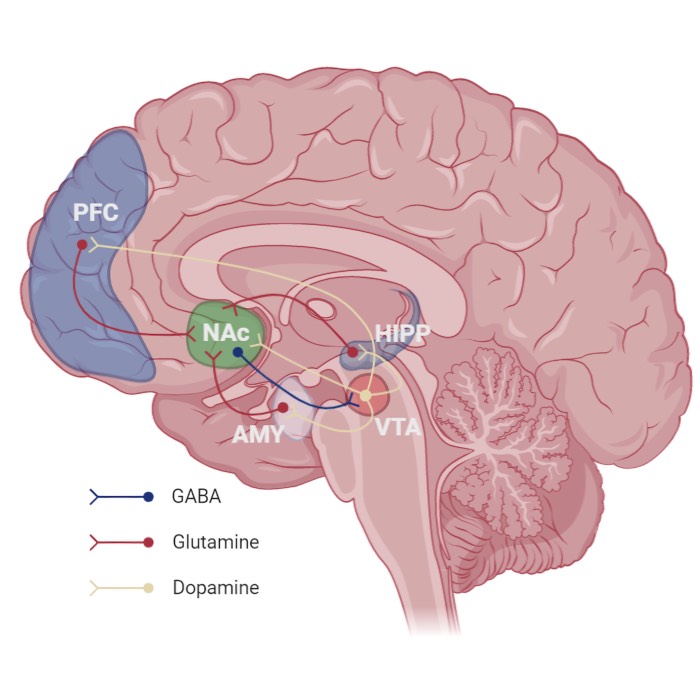

In such scenarios, it becomes difficult to locate a single, unified self. Neither hemisphere alone can account for the full range of the patient’s behavior or knowledge. The sense of personal identity, it seems, is not the product of a central, indivisible core, but rather emerges from the integration and communication of multiple neural processes. When these processes are disconnected, so too is the illusion of a singular self.

Importantly, the split-brain data do not entail that two fully independent subjects arise within one organism. What they reveal is that the apparent unity of the self depends on normally functioning integrative mechanisms that coordinate distributed neural processes into a coherent whole. When these integrative pathways are selectively interrupted, the appearance of unity dissolves, and fragmented patterns of agency become experimentally observable. This interpretation fits the early Buddhist analysis particularly well: it supports the view that what we call a self is contingent, constructed, and process-based rather than an essential entity.

This conclusion resonates with the early Buddhist claim that the self is not a substance but a designation, arising from the dynamic interaction of body, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness. Siddhartha Gautama’s rejection of the ātman did not deny that persons exist conventionally, but insisted that what we call a self is nothing more than a convenient label for a shifting process. In the split-brain studies, this shifting nature becomes vividly apparent. The normal, seamless operation of the brain gives rise to an impression of unity; when disrupted, that unity dissolves into a plurality of perspectives.

Toward a neuroscience-informed interpretation of anattā

Of course, the philosophical traditions underlying Buddhist thought and modern neuroscience differ significantly in their aims and methods. Siddhartha’s analysis of the aggregates was intended to support ethical and soteriological goals, namely, the cessation of suffering through detachment from what is impermanent and not-self. Neuroscience, by contrast, tends to avoid normative claims and focuses on describing how the brain works.

Still, the convergence is noteworthy. Both perspectives undermine the idea of a metaphysically real, unchanging self. Both suggest that what we take to be “I” is assembled from multiple components, none of which alone or in combination justifies the claim to an enduring self. And both point to the importance of understanding the conditions and processes that give rise to experience, rather than positing an entity that stands apart from them.

Split-brain cases offer a unique window into how fragile and contingent our self-model really is. They show that under certain conditions, even a neurologically intact person may behave as if they were two distinct agents. Recent research, however, interprets these phenomena as disruptions of integrative network activity rather than as evidence for the emergence of two independent minds. And when one hemisphere is cut off from the other’s input, it does not remain silent, but instead creates an explanation ex post facto, highlighting the brain’s deep narrative impulse. This aligns with the Buddhist insight that the self is a narrative construct, woven by the mind to make sense of experience.

Conclusion

The exploration of split-brain research in light of Buddhist philosophy reveals a compelling convergence between ancient introspective insights and modern empirical science. As demonstrated in the classic experiments involving patients with severed corpus callosums, the disruption of inter-hemispheric communication results in a fragmentation of conscious experience. This fragmentation casts doubt on the existence of a single, unified self. Instead, what appears is a model of the self as a dynamic, constructed narrative assembled from discrete, context-sensitive processes, a model that resonates deeply with Siddhartha Gautama’s doctrine of anattā.

Sebastian Gäb’s interpretation of these findings is both clear and provocative: he suggests that the self, as revealed in these experiments, is an emergent fiction. When the normal mechanisms of cognitive integration break down, so too does the illusion of a coherent “I”. This interpretation continues to hold up well in light of recent developments in neuroscience (see, e.g., Tononi & Koch (2015)ꜛ, Dehaene & Changeux (2011)ꜛ). Although today’s research emphasizes more complex, network-based models of consciousness rather than strict lateralization, split-brain results are now best understood as demonstrations of how vulnerable integrative networks are, rather than as proof of two fully separate consciousnesses. Still, the basic insight remains valid: there is no central homunculus directing experience from within. Rather, consciousness appears distributed, contingent, and narratively organized.

Western thought has historically leaned toward essentialist conceptions of the self, influenced by theological doctrines of the soul or Cartesian ideas of an indivisible subject. Even within secular philosophy and psychology, the tendency to posit a stable ego has been strong. Buddhism, in contrast, offers a radically different account that avoids this essentialism. By denying the existence of a fixed self and instead focusing on the impermanent and conditioned nature of mental and physical processes, it anticipates many of the implications drawn from split-brain and cognitive neuroscience.

This comparative advantage is not merely philosophical; it also has practical relevance. The Buddhist framework fosters a flexibility of identity and a detachment from the illusion of fixed ego-structures. In an age increasingly aware of the constructed nature of selfhood, through both psychology and neuroscience, Buddhist insights into non-self may offer a more realistic and adaptive approach to understanding human consciousness.

References and further reading

- Wikipedia article on the split brain syndromeꜛ

- The Split Brain Experiments, Nobel Mediaꜛ

- Vaddiparti, A., Huang, R., Blihar, D., DuPlessis, M., Montalbano, M. J., Tubbs, R. S., & Loukas, M., The evolution of corpus callosotomy for epilepsy management, 2021, World Neurosurgery. 145: 455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.08.178ꜛ

- Tononi, G., & Koch, C., Consciousness: here, there and everywhere? 2015, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1668), 20140167, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0167ꜛ

- Dehaene, S., & Changeux, J.-P., Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing, 2011, Neuron, 70(2), 200–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.018ꜛ

- Dennett, D. C., Consciousness Explained, 1992, Back Bay Books, ISBN: 978-0316180665, Wikipedia entryꜛ

- Churchland, P. S., Brain-wise: Studies in neurophilosophy, 2002, MIT Press, ISBN: 978-0262532006

- Gazzaniga, M. S., Cerebral specialization and interhemispheric communication: Does the corpus callosum enable the human condition?, 2000, Brain, 123(7), 1293–1326, doi: doi: 10.1093/brain/123.7.1293ꜛ

- Gallagher, S., How the Body Shapes the Mind, 2006, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199204168

Footnotes

-

Modern research, however, suggests that some interhemispheric integration persists through subcortical pathways, meaning that ‘two independent consciousnesses’ should be viewed as a theoretical interpretation rather than a strict empirical claim. ↩

comments