Consciousness and the ‘hard problem’ from a Buddhist angle

The “hard problem” of consciousness, famously articulated by philosopher David Chalmers (1995)ꜛ, refers to the difficulty of explaining how and why subjective experiences arise from physical processes in the brain. While modern neuroscience and philosophy of mind continue to struggle with this enigma, Buddhist thought, particularly as taught by Siddhartha Gautama and developed in later traditions, offers a radically different approach. Rather than positing consciousness as an inexplicable emergent property of matter or an irreducible substance, Buddhism treats consciousness as a contingent, dependently originated phenomenon (paṭiccasamuppāda). In this post, we explore how Buddhist philosophy reframes the hard problem, offering insights that challenge both reductionist materialism and metaphysical dualism.

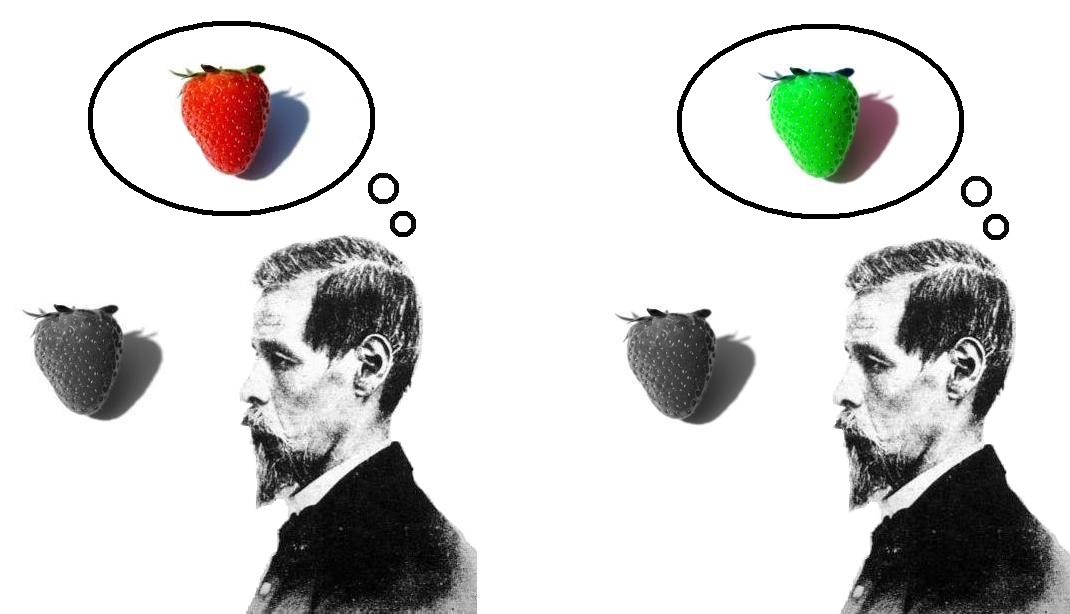

The hard problem is often illustrated by appealing to the logical possibility of inverted visible spectra. If there is no logical contradiction in supposing that one’s colour vision could be inverted, it follows that mechanistic explanations of visual processing do not determine facts about what it is like to see colours. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5).

The hard problem and its challenges

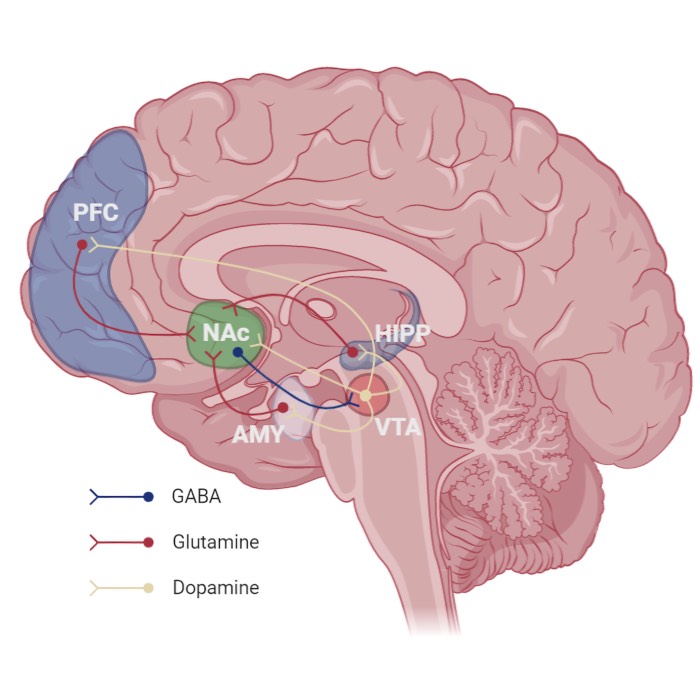

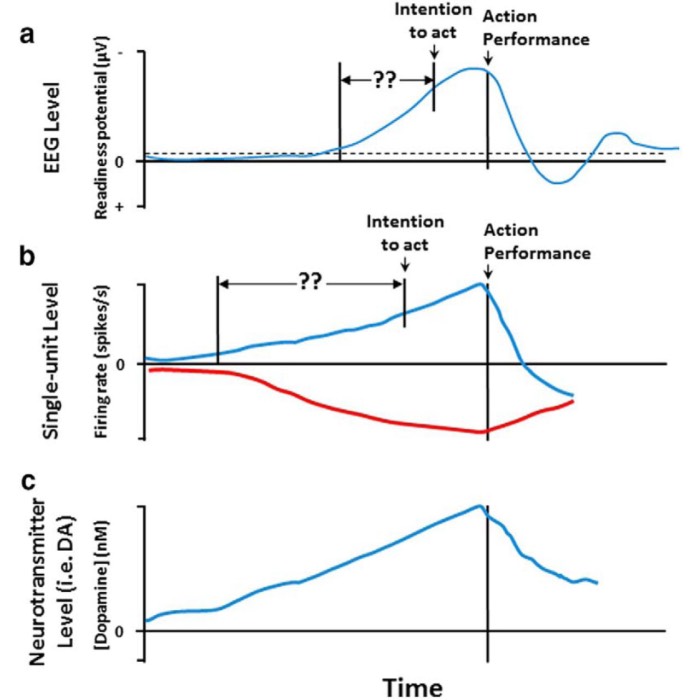

The “hard problem” of consciousness, as formulated by David Chalmers (1995)ꜛ, refers specifically to the difficulty of explaining why and how subjective experiences arise from physical processes in the brain. It is relatively straightforward for science to map neural activity to behaviors, perceptions, or cognitive functions, for instance, identifying which brain areas light up when a person sees a red apple or feels pain. These are sometimes called the “easy problems” of consciousness.

The hard problem, however, asks a deeper question: Why does any of this neural activity produce an inner, subjective feeling? Why does seeing a red apple not simply involve processing wavelengths of light, but also evoke the vivid experience of “redness”? Why does brain activity result in the feeling of joy, sadness, or pain, rather than being purely mechanical and devoid of experiential qualities?

This subjective, first-person perspective, often referred to as qualia, is difficult to explain through physical processes alone. Physicalist theories, such as identity theory and functionalism, attempt to equate mental states with brain states or define them by their functional roles, but critics argue that they miss this essential phenomenological dimension (Chalmers, 1996ꜛ).

Conversely, dualistic theories posit consciousness as fundamentally distinct from matter, but then face the problem of explaining how two radically different substances could interact causally. Thus, the hard problem persists as a central philosophical and scientific puzzle. Physicalist theories, such as identity theory and functionalism, attempt to reduce consciousness to neural processes, but critics argue that these approaches miss the essential phenomenological dimension (Chalmers, 1996ꜛ).

Conversely, dualistic theories posit consciousness as fundamentally distinct from matter, yet struggle to explain how two radically different substances could causally interact. Thus, the hard problem persists as a central philosophical and scientific puzzle.

Buddhist analysis of consciousness (viññāṇa)

In early Buddhist texts, consciousness (viññāṇa) is not treated as a metaphysical absolute but as one of the Five Aggregates (khandha) that constitute experience. Consciousness is defined functionally: it arises in dependence upon sense bases (āyatana) and their corresponding objects (e.g., eye and visible form, ear and sound).

The Mahā-nidāna Sutta (DN 15) describes consciousness as arising conditionally, without any suggestion of an underlying, unchanging self. Rather than existing independently, consciousness is embedded in a network of causal relations. This view precludes both materialistic reductionism and substance dualism.

Furthermore, the Paṭṭhāna (the Theravāda Abhidhamma’s conditional relations) elaborates detailed schemes showing that consciousness and mental factors arise in intricate patterns of co-dependence. No singular, isolated “thing” called consciousness exists apart from these dynamic relations.

Implications for the hard problem

From a Buddhist perspective, the hard problem is reframed. The issue is not how subjective experience emerges from matter, but how mistaken reification of processes into substances creates confusion. Consciousness is not a “thing” that needs to be located within matter or separated from it; it is a process, arising and ceasing according to conditions.

This relational, process-oriented view resembles certain contemporary approaches in philosophy of mind, such as enactivism and process philosophy (Thompson, 2007ꜛ). However, Buddhism goes further by insisting that insight into the contingent nature of consciousness can be cultivated through direct meditative experience, ultimately leading to the cessation of suffering.

Importantly, Buddhism does not deny the existence of subjective experience. Rather, it treats subjective awareness as part of the field of conditioned phenomena, characterized by impermanence (anicca), non-self (anattā), and unsatisfactoriness (dukkha).

Meditation and direct investigation of consciousness

Meditative practices, especially those emphasizing mindfulness (sati) and insight (vipassanā), serve as empirical methods for investigating consciousness firsthand. Advanced practitioners report observing the arising and passing away of moments of awareness, thereby weakening the intuitive sense of a continuous subject.

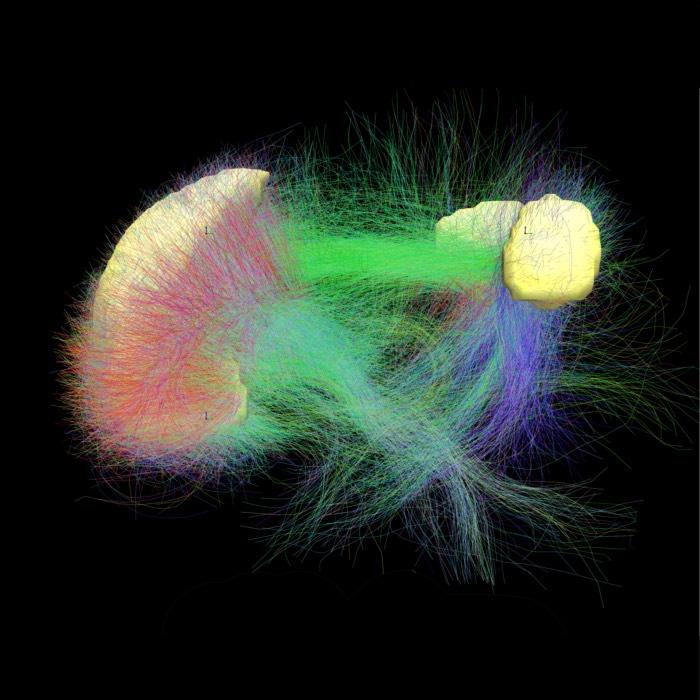

Studies in contemplative neuroscience show that long-term meditators can alter their baseline states of consciousness, shifting away from habitual self-referential processing (Lutz et al., 2008ꜛ). These findings suggest that the experience of consciousness as dynamic, fragmented, and selfless is not merely a philosophical speculation but an empirical possibility.

Critical reflections

While Buddhism offers a compelling reframing of the hard problem, certain differences with contemporary science must be acknowledged. Buddhism is primarily soteriological, i.e., its concern is the alleviation of suffering, not the construction of a comprehensive theory of mind.

Moreover, Buddhist analysis operates at a phenomenological and pragmatic level, not attempting to provide a materialist explanation of neural correlates. Thus, while Buddhist insights can inform philosophical debates, they do not replace the need for scientific inquiry into the brain’s functioning.

Nevertheless, the Buddhist approach reminds us that conceptual categories, such as “mind” and “matter”, are themselves constructions that may obscure the fluid, interdependent nature of experience. This offers a profound philosophical challenge to any rigid metaphysical position.

Conclusion

The hard problem of consciousness remains unresolved within the framework of contemporary science. Buddhist philosophy, by refusing to reify consciousness as either a substance or an epiphenomenon, offers a different path: one that treats awareness as a contingent, relational process. Through meditation and direct observation, it invites practitioners to transcend conceptual confusions and to recognize the impermanent, non-self nature of consciousness. In doing so, it shifts the focus from explaining consciousness to transforming our relationship to it, a move with profound philosophical and existential implications.

References and further reading

- Chalmers, D. J., Facing up to the problem of consciousness, 1995, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2(3), 200–219, online PDFꜛ

- Chalmers, D. J., The conscious mind: In search of a fundamental theory, 1996, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195117899, Wikipedia article on the bookꜛ, online PDFꜛ

- Koch, C., Massimini, M., Boly, M., & Tononi, G., Neural correlates of consciousness: Progress and problems, 2016, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(5), 307–321, doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.22ꜛ

- Lutz, A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J., Meditation and the neuroscience of consciousness, 2007, in Zelazo, P. D., Moscovitch, M., & Thompson, E. (Eds.), Chapter 19, In: The Cambridge handbook of consciousness, Cambridge University Press, doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511816789ꜛ

- Thompson, E., Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind, 2007, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674057517, Thompson’s homepage about his bookꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the hard problem of consciousnessꜛ

comments