How languages begin and vanish: A short follow-up to our series on language and writing systems

Almost exactly one year ago, I wrote a short series on the origins of languages and writing systems (see “Related posts from our previous series” below). In that series, we explored how writing systems emerged from earlier forms of communication, how they shaped human history, and how different cultures developed their own unique scripts.

A recent documentary on Arteꜛ addressed the question of whether all humans once shared a single ancestral language. An interesting topic and I thought that it would be an ideal opportunity to return to this subject. In this post I therefore summarize and discuss the main points of the documentary, which continues the themes from last year’s series, but examines them from a different angle. Here, the focus is on spoken language itself: how humans create new forms of communication, how languages evolve, and how easily many of them vanish. Thus, this time we shift from writing systems back to the spoken languages that underlie them.

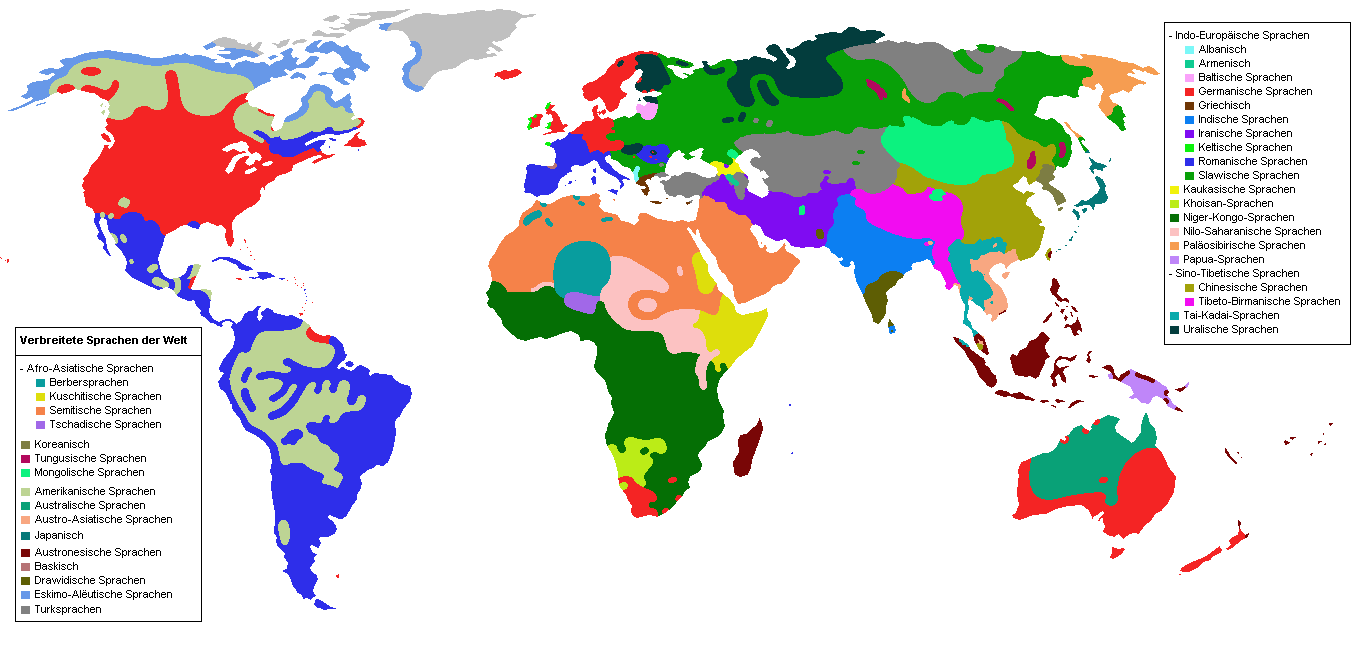

Language families of the world (only spoken languages). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Language families of the world (only spoken languages). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

In the following sections I summarize the main arguments from the documentary and add some of my own reflections. My goal is not to provide a full review but to highlight what I found most interesting and relevant, especially in relation to last year’s series.

The invention and evolution of language

The documentary opens with the idea that language is the most consequential development in human history, yet also the one whose origins are most inaccessible. Spoken language disappears the moment it is produced, and because early humans had no writing system, nothing from its beginnings is preserved. Everything about these earliest stages must therefore be inferred. Without direct evidence, research relies on what we know about how humans communicate today and what kinds of situations require structured communication in the first place.

Early Homo sapiens groups needed ways to coordinate tasks, clarify intentions, and establish shared references, and over generations such processes gave rise to full languages, long before the historical families described in classical linguistics emerged. Wherever such coordination was necessary, some form of language could emerge. A simple example illustrates this: two people who do not share a vocabulary often begin with gestures, establish the first successful signs as shared conventions, and gradually build a functional communicative system. Extended across communities and generations, such processes can give rise to full languages.

These are only the bare structural conditions. Early language almost certainly grew out of concrete, everyday situations in which people had to cooperate, solve problems together, or react to danger. Communication began as improvised attempts to make intentions clear, to coordinate movement, or to negotiate access to resources. When a gesture or sound reliably achieved its purpose, it became a shared shortcut within the group; repeated use in familiar situations slowly turned such improvised signals into stable, recognizable patterns. With time, these small, situation‑bound routines would have expanded into more expressive systems. The emergence of language was therefore most likely not a single event, but a long, cumulative process driven by practical needs, social bonds, and the constant pressure to make collective life workable.

Babel myth and scientific uncertainty

As an illustration, the documentary turns to the familiar image of the Tower of Babel. The story suggests that humanity once shared a single language which later fractured into many. It is a neat explanation, but nothing in the history of early human communication supports it. The contrast between the myth and what we can reasonably say about the beginnings of language is sharp. Instead of a unified linguistic past, the evidence points toward something far less orderly: small groups of early humans, separated by distance and environment, each developing their own ways of expressing what mattered in their daily lives.

What makes this question difficult is that spoken language leaves no trace. Without writing, nothing is recorded, and the earliest periods of linguistic history are therefore inaccessible. Researchers cannot recover “the first language” because there is no material to study. All we can do is work from indirect clues and from what we know about how communication works today. The uncertainty here is not a temporary gap that future discoveries will fill but a structural limit of the subject.

This uncertainty marks the limits of what can be reconstructed and forces us to accept that early linguistic evolution cannot be recovered in detail. The myth of a single original language offers a clear narrative; the reality, however, is almost certainly a long and fragmentary process shaped by many different groups, none of which left behind the evidence needed to give us a definitive answer.

Communication without a shared language

One of the most concrete points in the documentary concerns what happens when people have no shared language at all. Human communication does not collapse in such situations; instead, it reorganizes itself. Interaction begins with gestures, pointing, mimicry, and whatever signs can be improvised on the spot. Most of these attempts fail, but the few that succeed become anchors for further exchanges. Once both sides have agreed—implicitly—that a particular gesture corresponds to a specific intention, it becomes a reusable tool. The next interaction is shorter, clearer, and more efficient. A miniature communicative system begins to form.

This mechanism is not limited to marketplaces or travel scenarios. It reflects something general about how humans solve communicative obstacles. Whenever two groups cannot rely on a common vocabulary, they create provisional systems that stabilise through repetition. Over time, these provisional systems reduce ambiguity, become more structured, and allow increasingly abstract meanings to be expressed. The documentary uses this to illustrate how early language might have started: not as a deliberate invention, but as a gradual accumulation of successful strategies for making oneself understood.

Language as a driver of human social evolution

A central idea is that language did not simply emerge alongside human social life but began to reshape it. Once groups could argue, negotiate, reassure, warn, and coordinate through words rather than through physical confrontation, the pressure to resolve conflicts violently decreased. The idea is often described as a kind of “self‑domestication”: instead of relying on aggression, early humans increasingly shifted parts of their conflict management into verbal space. This shift altered which behaviours were advantageous. Individuals who could communicate clearly, diffuse tensions, or navigate social situations with words rather than force gained an edge.

Language therefore amplified the importance of cooperation. The more people relied on verbal exchange, the more social networks expanded, and the more complex these networks became, the greater the demand for flexible, expressive communication. This created a feedback loop: more cooperation required more language, which in turn enabled even larger and more stable groups. Rather than a tool added onto an already finished species, language became one of the forces that shaped what humans eventually became.

Why a single proto-language is unlikely

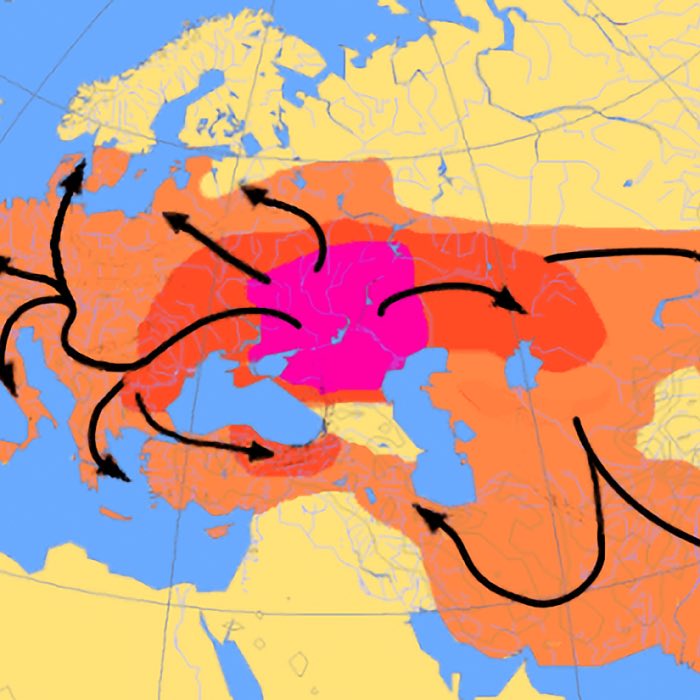

The idea of a single ancestral language is appealing because it offers a clean origin story, which would provided a tracable root for all so-far known proto-languages, such as the Indo-European language family, but nothing in early human history points in that direction. Small groups of Homo sapiens lived far apart, often separated by geography, climate, and minimal contact. Under such conditions, it is improbable that they would all develop or maintain the same system of communication. Language is tied to the daily realities of the group that uses it, shaped by its environment, shared tasks, and local forms of cooperation. Different groups facing different conditions would naturally develop different ways of expressing what mattered to them.

Even if some early forms of communication were loosely similar, they would have diverged quickly. Languages shift constantly as people adapt them to new situations, new needs, and new social dynamics. Without sustained contact between groups, there is nothing to keep these systems aligned. Over generations, even small differences accumulate until mutual intelligibility disappears. What emerges is not a branching tree from a single trunk but many small beginnings developing in parallel, influenced by local circumstances rather than by a single common source.

The rise of linguistic diversity and the modern dominance of a few languages

The documentary states that humanity today speaks between roughly 6500 and 7000 languages, yet most of the global population uses only a very small handful of them. This contrast between immense diversity on one side and overwhelming dominance on the other is not a natural outcome of linguistic evolution but the result of historical forces that reshaped entire regions. For most of human history, languages were deeply local, tied to specific communities, landscapes, and forms of life. The patchwork of dialects and minority languages that once defined much of the world reflects this long period in which groups lived with limited mobility and limited large‑scale political integration.

The modern dominance of languages such as English, Mandarin, Hindi, Spanish, or French is therefore historically young. It emerged through imperial expansion, colonial administration, state formation, and the spread of standardized schooling. These processes elevated certain languages to the status of administrative, commercial, or cultural norms while pushing many others into marginal positions. Linguistic diversity did not shrink because smaller languages were inherently weaker or less expressive but because the social, political, and economic structures that once sustained them were dismantled or absorbed into larger systems.

The resulting landscape is one in which a few large languages are globally present while thousands remain confined to small communities or face the threat of disappearing altogether.

Nation building and linguistic unification in Europe

The documentary uses France as a clear example of how modern nation states reshaped the linguistic landscape. At the time of the Revolution, the language we now call Standard French was not the everyday language of most people in the country. Large parts of the north spoke local dialects such as Norman or Picard, the west spoke Breton, the south used Occitan, and other regions relied on Basque or Catalan varieties. Many communities understood only fragments of the official language, and some did not understand it at all.

This situation created real confusion, especially when political decisions had to be communicated to the population. One striking case mentioned is a rebellion in which rural communities misinterpreted an official decree because the word “décret” was associated with arrests in old usage. Their reaction was not ideological; they simply misunderstood what the officials intended to announce.

Such incidents convinced revolutionary leaders that a unified republic required a unified language. The Abbé Grégoire conducted a detailed survey and concluded that only a small minority of the population spoke French fluently. His answer was uncompromising: local dialects and minority languages should disappear, and a single national language should bind the country together. For decades, this ambition remained largely theoretical, but with the later expansion of a centralized school system, linguistic unification became enforceable. Children who continued to speak Breton, Occitan, or Catalan in the schoolyard were punished, and regional languages were labelled impure or backward.

The push for a single national language shaped not only French identity but also the identities of communities who resisted this pressure. In Brittany, Provence, and the Basque regions, linguistic difference eventually became a marker for political and cultural demands for autonomy. Language became a boundary line both for the nation state and for those who felt excluded by its definition.

Constructed universal languages: Volapük and Esperanto

The documentary turns to the nineteenth century, when the rapid spread of postal systems, telegraph lines, railways, and standardized time zones created an unprecedented sense of global connectedness. At the same time, nationalist movements in Europe were elevating individual languages into symbols of statehood. This produced a tension: communication across borders became easier than ever, yet linguistic divisions hardened.

Out of this moment grew the idea of a deliberately crafted universal language. Volapük was the first major attempt. Its creator, Johann Martin Schleyer, wanted a language that anyone could learn quickly and pronounce unambiguously. To him, the practical problem was not abstract philosophy but the simple fact that letters from Europe to America often failed to arrive because the addresses were written phonetically—and incorrectly—by emigrants who did not speak English. A universal language with regular spelling seemed like a direct solution.

Volapük spread with surprising speed. Hundreds of thousands of people learned it, clubs were founded, and there were even plans for Volapük ships and airships. But the language carried two problems that ultimately hindered it. First, many of its words were so heavily modified from their European sources that even speakers of those languages found them unintuitive. Second, Schleyer refused to accept suggestions for reform. He treated the language as something fixed, not as something that could evolve with its community of users.

It was precisely this rigidity that pushed many early enthusiasts toward a new project: Esperanto. Unlike Volapük, Esperanto was designed to be open to revision and collective shaping. Its vocabulary was easier to recognize, its grammar more transparent, and the community surrounding it more willing to adapt. The contrast between the two projects highlights a broader point about language itself: systems that cannot change tend not to survive, whereas those that remain flexible can grow with the people who use them.

Linguistic arrogance and the problem of frozen languages

One striking aspect in this story is how quickly a language project collapses when it is treated as something untouchable. In the case of Volapük, the turning point was not its structure alone but the attitude surrounding it. Schleyer insisted that his creation remain exactly as he had designed it, resisting even modest adjustments proposed by its own community of speakers. This rigidity created the very conditions under which the language could no longer grow. Once a system freezes, it stops reflecting the needs and intuitions of the people who use it.

The contrast to natural languages is instructive. Every spoken language changes constantly—vocabulary shifts, grammar drifts, pronunciations evolve. This is not a sign of decay but a universal feature of how communication works. A language that cannot change cannot survive. The problem with Volapük was therefore not simply technical difficulty but the belief that a language could be perfected once and for all. As soon as it stopped adapting, it lost its users, many of whom moved on to Esperanto precisely because it allowed for collective shaping and organic development.

Language, identity, and cultural survival: The Menominee case

A final strand in this broader story concerns what happens when a language is not merely shaped by historical forces but actively suppressed. The Menominee example shows, in a very concrete way, how language loss unfolds across generations and what it means for a community when its linguistic foundations are deliberately broken.

The situation of the Menominee in Wisconsin builds directly on this contrast between linguistic resilience and vulnerability. The Menominee are an Indigenous nation whose ancestral territory lies in the Great Lakes region, and their experience shows in stark detail what happens when outside forces deliberately target a language. For generations, government‑run boarding schools separated children from their families and punished them for speaking Menominee. Over time, this pressure broke the natural chain of transmission. By the early 2000s, only a handful of speakers remained, and everyday use had nearly disappeared.

The loss was not only linguistic. With the language went stories, ecological knowledge, names for plants and landscapes, and a sense of continuity with previous generations. Elders described the language as the “soul” of the community: without it, cultural life becomes hollow, and memories lose their anchor.

The current revitalisation effort therefore begins as early as possible in childhood. Teachers are trained intensively, and immersion classes introduce the language to children from infancy onward. No translation is used; meaning is learned directly from context, through repeated interaction, gestures, and routines. Each new speaker shifts the situation slightly, making the language less dependent on the remaining elders and more rooted again in daily life.

The goal is modest but vital: not to return to an imagined past, but to keep the language alive by ensuring that it is spoken, heard, and responded to. As soon as families begin raising children with the language again, extinction is no longer determined by the lifespan of a single speaker but by the willingness of a community to carry its knowledge forward.

What linguistic diversity means today

The documentary’s final point is that linguistic diversity is not a decorative excess but a record of how different communities perceive the world. Each language encodes distinctions, habits of attention, and layers of knowledge that reflect the experiences of the people who speak it. When a language disappears, these ways of seeing do not migrate neatly into another system; they vanish with it. At the same time, global communication has never been easier, and large languages continue to expand through media, education, and migration. This creates a tension: the world becomes more connected, yet many smaller languages move closer to disappearance. Preserving diversity therefore means more than documenting vocabulary—it means creating conditions in which communities can continue to use their languages in daily life, pass them on, and keep the perspectives embedded in them alive.

Conclusion

Looking back at these different strands, I see a simple pattern emerging. Human language has never been static, uniform, or neatly ordered. In my view, it began in improvised exchanges, expanded through cooperation, fractured through distance, hardened through politics, and in many places was violently disrupted. Yet it also carries the weight of memory, identity, and local knowledge with a precision that no substitute can fully preserve.

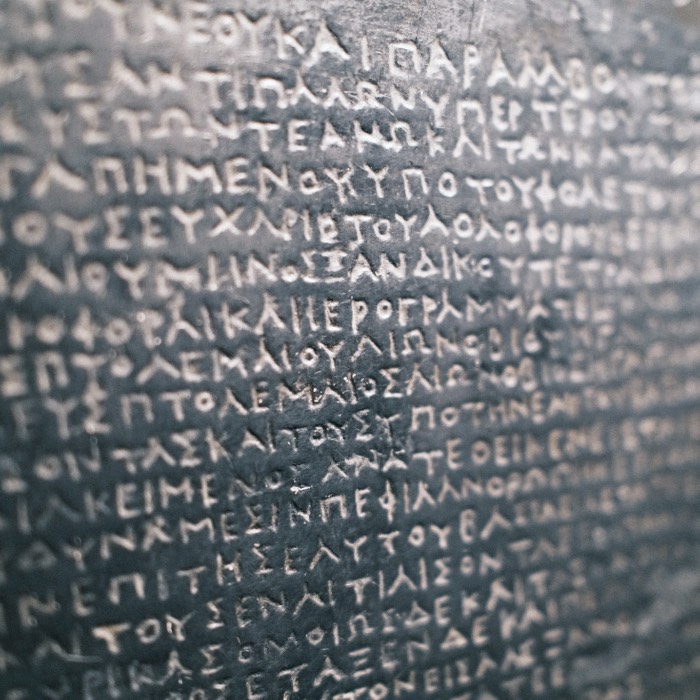

What strikes me most, compared to last year’s series, is the shift in perspective: instead of following the written traces that allow us to reconstruct linguistic history, this material draws attention to what happens before writing, below writing, and outside of writing. In my view, it highlights how every script, every literary tradition, and every standardized language rests on far older layers of spontaneous human problem‑solving and social negotiation.

I suspect that the tension between global connectivity and shrinking linguistic diversity will only grow stronger. Large languages spread through education, media, and mobility, while many smaller ones survive only because communities actively choose to hold on to them. Diversity persists where it remains lived, not merely archived. And the examples here show that even when a language is pushed to the edge, revival is possible—if people decide that their way of speaking, seeing, and remembering is worth carrying forward.

References and further reading

- Arte documentary on “Haben wir früher ALLE DIESELBE SPRACHE gesprochen? – Stimmt es, dass…?”ꜛ (streamed on Nov. 11, 2025)

- Wikipedia article on Languageꜛ

Related posts from our previous series:

- A brief history of writing

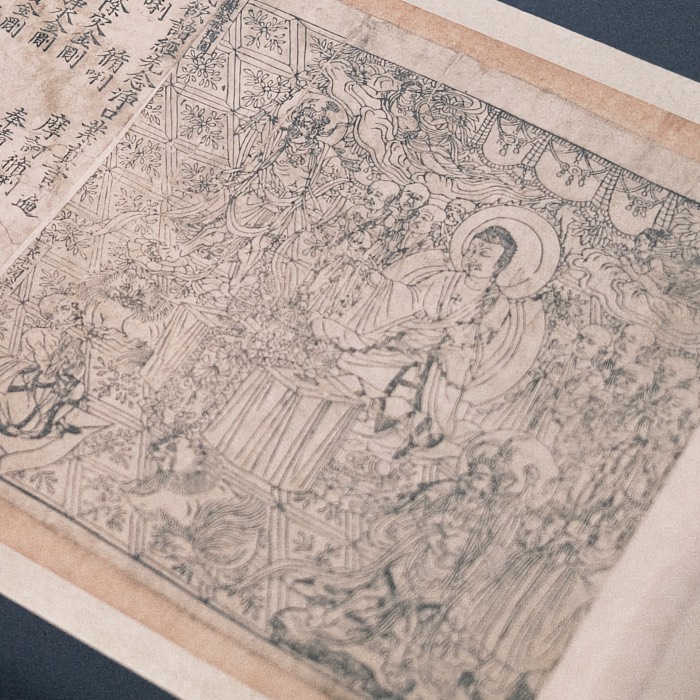

- Book printing before Gutenberg: The Asian roots of printing technology

- The Indo-European language family: Linguistic roots of European and South Asian civilizations

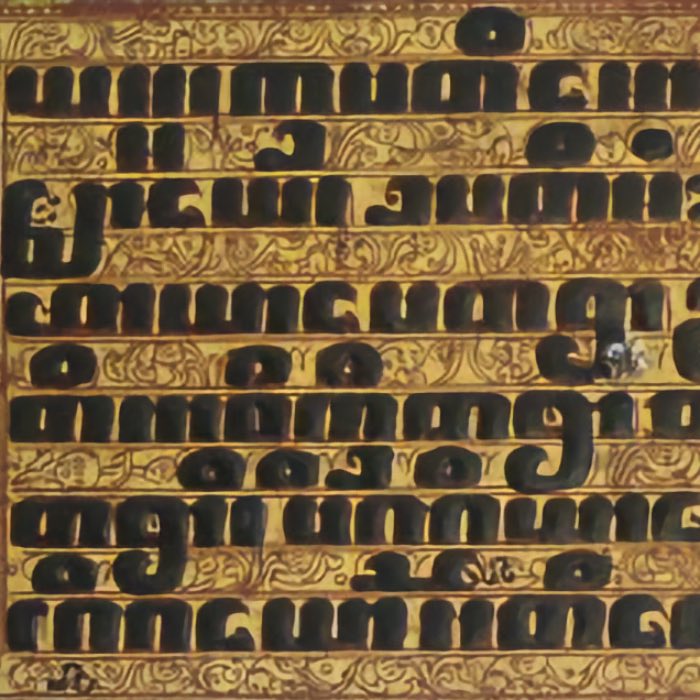

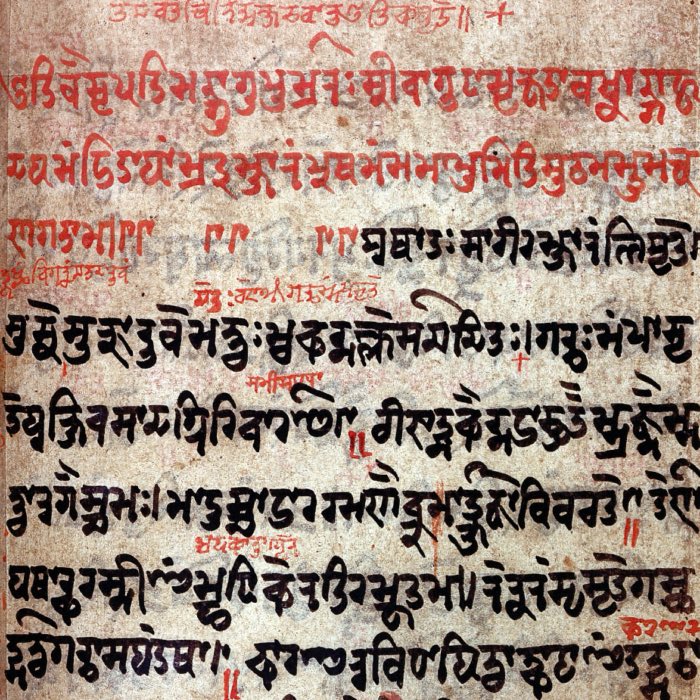

- Sanskrit: Sacred language of ancient India

- Pali: Language of Buddha’s teachings

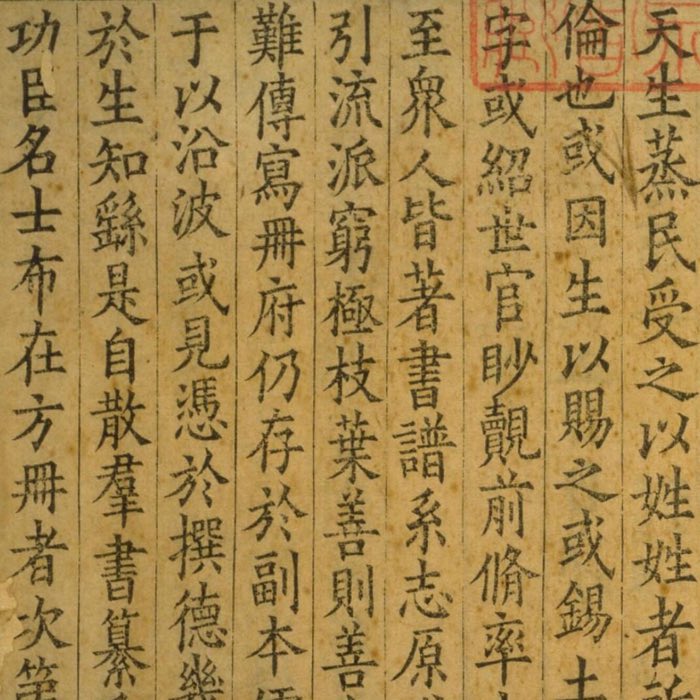

- Origins of the Chinese language and writing system

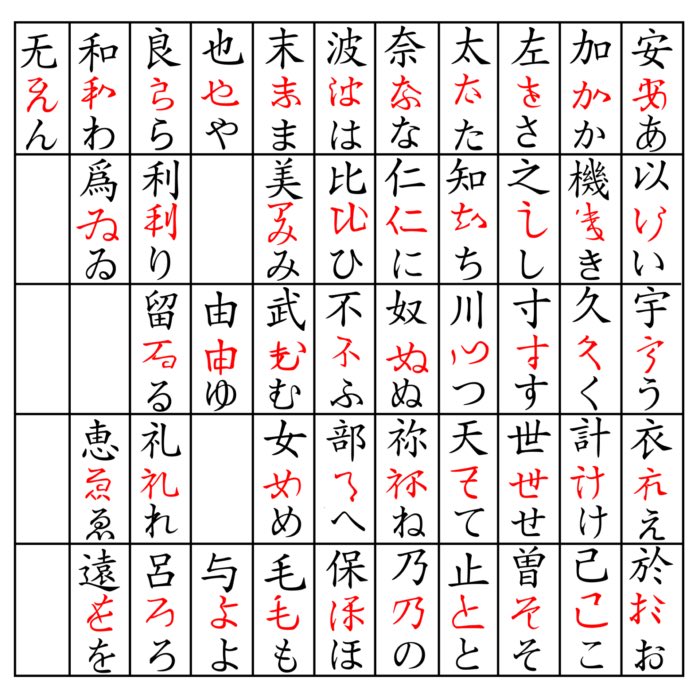

- The Japanese language and writing systems: Origins of a unique linguistic heritage

Book recommendations:

- Deutscher, Guy, Die Evolution der Sprache, 2022, C.H. Beck, ISBN: 978-3406783685

- Janson, Tore, Eine kurze Geschichte der Sprachen, 2010, 978-3827417787, ISBN: 978-3827417787

- Weinrich, Harald, Sprache, das heißt Sprachen, 2006, Narr Francke Attempto, ISBN: 978-3823362043

- Störig, Hans-Joachim, Die Sprachen der Welt, 2022, Anaconda Verlag, ISBN: 978-3730610787

- Jackendoff, Ray, Foundations of language: Brain, meaning, grammar, evolution, 2003, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199264377

- Fitch, W. Tecumseh, The evolution of language, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521677363

- Hurford, James R., The origins of language: A slim guide, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198701880

- Hurford, James R., The origins of meaning: Language in the light of evolution, 2007, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199207855

- Deacon, Terrence W., The symbolic species: The co-evolution of language and the human brain, 1997, W.W. Norton, ISBN: 978-0393317541

- Trudgill, Peter, Sociolinguistic typology: Social determinants of linguistic complexity, 2011, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199604357

- Thomason, Sarah G. & Kaufman, Terrence, Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics, 1988, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520057890

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y., Language contact in Amazonia, 2002, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199588244

- Nettle, Daniel, Linguistic diversity, 1999, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0191592812

- Evans, Nicholas, Dying words: Endangered languages and what they have to tell us, 2009, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-0631233060

- Crystal, David, Language death, 2014, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1107431812

- Pinker, Steven, The language instinct: How the mind creates language, 1994, William Morrow, ISBN: 978-0688121419

- Tomasello, Michael, Origins of human communication, 2008, MIT Press, ISBN: 978-0262201773

- Clark, Herbert H., Using language, 1996, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521567459

- Ostler, Nicholas, Empires of the word: A language history of the world, 2006, HarperCollins, ISBN: 978-0007118717

- McWhorter, John, The power of Babel: A natural history of language, 2003, Harper Perennial, ISBN: 978-0060520854

comments