The Basilica of St. Servatius as a symbol of the complexity of European cultural heritage

In August 2025, I spent a day in Maastricht and visited the Basilica of St. Servatius. I did not come with a checklist or a plan to study Romanesque sculpture. I came because I was in the city by chance, and because the basilica is one of those places that quietly insist on being entered I guess.

Basilika von Sankt Servatius in Maastricht, Netherlands.

Basilika von Sankt Servatius in Maastricht, Netherlands.

Maastricht itself already feels like a city shaped by transitions. It lies between countries, languages, and political histories, and it has been doing so for a very long time. Historically, that “in between” status was not just a feeling. Maastricht grew around a Meuse crossing that mattered already in Roman times, on the road corridor between Tongeren and Cologne. Even later, the city kept ending up under shared or contested rule, which makes the border city vibe feel less like a modern European pose and more like an old habit. The basilica fits into this almost too well. It stands next to the Vrijthof, a large square surrounded by shops, cafes, and streets busy with locals and tourists, not as a distant monument, but as something that is an integral part of the rhythm of the city.

In this post, I’d therefore like to share some reflections on that visit, focusing on how the basilica embodies the layered and often contested nature of European cultural heritage.

Main entrance portal of the Basilika.

Main entrance portal of the Basilika.

A place built from layers

The site has been religiously active since late antiquity. Churches have stood here for more than a millennium, built around the grave of Servatius, a bishop associated with the early Christianization of the region. A small memorial chapel over the tomb is already attested in late antiquity, and whatever one thinks about the saint cult as such, the basic mechanism is easy to recognize: a grave becomes a point of focus, then a building, then a flow of visitors, then a whole urban rhythm around it. That continuity is easy to state as a historical fact, but it becomes more tangible once you step inside and realize how much of what you see is not about a single period, but about accumulation.

Stone sculpture in the outer walls of the Basilika.

Stone sculpture in the outer walls of the Basilika.

Treasury: Fragment of a stone relief.

Treasury: Fragment of a stone relief.

The basilica is Romanesque at its core, most of what you see today comes from the major building phases of the 11th and 12th centuries, but nothing about it feels frozen in time. It carries additions, restorations, losses, and repairs. It feels used, not preserved. The building does not present itself as a finished statement, but as something that has been negotiated again and again across centuries.

The alleged tomb of Saint Servatius.

The alleged tomb of Saint Servatius.

Inscriptions in the tomb of Saint Servatius.

Inscriptions in the tomb of Saint Servatius.

A wooden statue, most likely of Saint Servatius, at the entrance of the basilica.

A wooden statue, most likely of Saint Servatius, at the entrance of the basilica.

From the treasury, one can get a view of archaeological excavations below the basilica.

From the treasury, one can get a view of archaeological excavations below the basilica.

Detail of the round arch ornaments on the entrance portal.

Detail of the round arch ornaments on the entrance portal.

How space shapes behavior

Walking through the interior, I was less struck by individual artworks than by how the space guides behavior. Light is scarce and carefully placed. Sound lingers longer than you expect. Movement slows down without anyone asking you to slow down.

St. Servatius’ cloister walkway, which is fully covered by Gothic vaults and sourounds the inner courtyard of the basilica.

St. Servatius’ cloister walkway, which is fully covered by Gothic vaults and sourounds the inner courtyard of the basilica.

Even without believing in anything specific, you start acting differently almost immediately. You lower your voice. You pause. You look more carefully. None of this feels accidental. Sacredness here is not an invisible property of the building. It is produced. And it is produced in a way that is very “medieval” in spirit: not by argument, but by choreography. Sightlines, thresholds, and small changes in elevation teach you where to linger and what to treat as important.

Along the cloister walkway, various stone sculptures are embedded in the walls.

Along the cloister walkway, various stone sculptures are embedded in the walls.

It emerges from architectural choices, from materials, from light, from thresholds and barriers. Certain areas draw attention through ornament, gold, or elevation, while others recede into shadow. Importance is spatially encoded. You do not need theological training to read it. Your body understands it before your mind does.

Here are some more impressions from within the basilica:

Richly decorated wooden altar piece of a side chapel.

Richly decorated wooden altar piece of a side chapel.

Crucifix hanging on the wall of the covered cloister walkway.

Crucifix hanging on the wall of the covered cloister walkway.

Gothic ceiling vaults of the cloister hallways.

Gothic ceiling vaults of the cloister hallways.

A detail of a Jesu Pantocrator relief over a door.

A detail of a Jesu Pantocrator relief over a door.

In a niche with remnants of wall paintings, a statue of Mary with child.

In a niche with remnants of wall paintings, a statue of Mary with child.

The main nave of the basilica.

The main nave of the basilica.

Ceiling of the main nave along with a hanging sculpture of Mary with child.

Ceiling of the main nave along with a hanging sculpture of Mary with child.

Ceiling vaults of the basilica.

Ceiling vaults of the basilica.

View into the altar area of the basilica.

View into the altar area of the basilica.

The frescoes over the altar area along with a large crucifix.

The frescoes over the altar area along with a large crucifix.

The frescoes over at the ceiling of the altar area seen from another angle.

The frescoes over at the ceiling of the altar area seen from another angle.

Wooden statue of a preciously decorated bishop or other important religious figure.

Wooden statue of a preciously decorated bishop or other important religious figure.

Detail view of a foldable wooden altar piece depicting various biblical scenes.

Detail view of a foldable wooden altar piece depicting various biblical scenes.

Another detail view of the wooden altar piece.

Another detail view of the wooden altar piece.

Detailed view of two figures on a wooden confessional booth.

Detailed view of two figures on a wooden confessional booth.

View into a small chapel below the main altar area.

View into a small chapel below the main altar area.

Altar area of the small chapel below the main altar area.

Altar area of the small chapel below the main altar area.

On of the side naves of the basilica.

On of the side naves of the basilica.

Stained glass window in the basilica.

Stained glass window in the basilica.

Panel (stained glass?) showing Mary with child and two angels.

Panel (stained glass?) showing Mary with child and two angels.

The so-called Bergportaal (mountain portal) of the basilica with richly decorated reliefs sourrounding the entrance.

The so-called Bergportaal (mountain portal) of the basilica with richly decorated reliefs sourrounding the entrance.

Bergportaal with the door open.

Bergportaal with the door open.

The Bergportaal is one of those thresholds where the building makes its point openly. The sculptural program sits right at the moment of entry, as if the church wants to decide the tone before you even step inside.

The Bergportaal is sourrounded by various sculptures embedded in the outer walls of the basilica.

The Bergportaal is sourrounded by various sculptures embedded in the outer walls of the basilica.

Mosaic of in form of a cross in the floor in front of the Bergportaal, showing the Celestial Jerusalem.

Mosaic of in form of a cross in the floor in front of the Bergportaal, showing the Celestial Jerusalem.

Stone relief depicting Christ the Pantocrator (top) and Mary with child (bottom).

Stone relief depicting Christ the Pantocrator (top) and Mary with child (bottom).

Embedded into the floor, tombstones of former religious figures.

Embedded into the floor, tombstones of former religious figures.

Another part of a tombstone embedded into the floor.

Another part of a tombstone embedded into the floor.

A modern stained glass window in the basilica.

A modern stained glass window in the basilica.

Wooden statue of standing Christ pointing to his heart.

Wooden statue of standing Christ pointing to his heart.

Giant statue of a king, playing o a harp while viewing towards the ceiling or heavens.

Giant statue of a king, playing o a harp while viewing towards the ceiling or heavens.

Objects, authority, and continuity

The treasury makes this especially clear. The reliquaries, textiles, and goldsmith works are impressive, but what struck me more was how explicitly they function as anchors of authority and continuity. These objects once circulated through the city during pilgrimages. They structured time, movement, and collective attention. That is still visible in the fact that Maastricht periodically stages a major relic pilgrimage, the Heiligdomsvaart, where the treasury becomes public again and the city turns into a route. Even when you visit on an ordinary day, the objects carry that “processional” intention.

Coats of arms over the entrace to the treasury.

Coats of arms over the entrace to the treasury.

Treasury: Bust reliquary of a saint or king.

Treasury: Bust reliquary of a saint or king.

Even today, displayed behind glass, they still carry traces of that role. Not because they are inherently sacred, but because generations were taught to treat them as such. Sacredness here has always been tied to use. It had to be maintained, narrated, displayed, and defended.

Treasury: Sculpture of an enthroned angel.

Treasury: Sculpture of an enthroned angel.

Treasure: Gilded panel of an armed saint (?).

Treasure: Gilded panel of an armed saint (?).

Treasury: Gilded lid of a reliquary box or sarcophagus (I actually forgot what it was).

Treasury: Gilded lid of a reliquary box or sarcophagus (I actually forgot what it was).

Treasury: Reliquary cross (‘Pectoral cross of Saint Servatius’), Cruciform reliquary, donated in 1039 by the Roman-German Emperor Henry III. Contains relics of the Holy Cross and of Saint Lawrence., 1020-1040, Trier, cherry wood, silver, gold, enamel, gemstones, ivory. This kind of donor inscription is also a reminder that relic prestige was never only local piety. It was connected to imperial patronage and to the political value of being seen as a protected and “important” sacred site.

Treasury: Reliquary cross (‘Pectoral cross of Saint Servatius’), Cruciform reliquary, donated in 1039 by the Roman-German Emperor Henry III. Contains relics of the Holy Cross and of Saint Lawrence., 1020-1040, Trier, cherry wood, silver, gold, enamel, gemstones, ivory. This kind of donor inscription is also a reminder that relic prestige was never only local piety. It was connected to imperial patronage and to the political value of being seen as a protected and “important” sacred site.

Treasury: Painting showing Mary with child (?) and other figures.

Treasury: Painting showing Mary with child (?) and other figures.

Treasury: Stone statue of a nun.

Treasury: Stone statue of a nun.

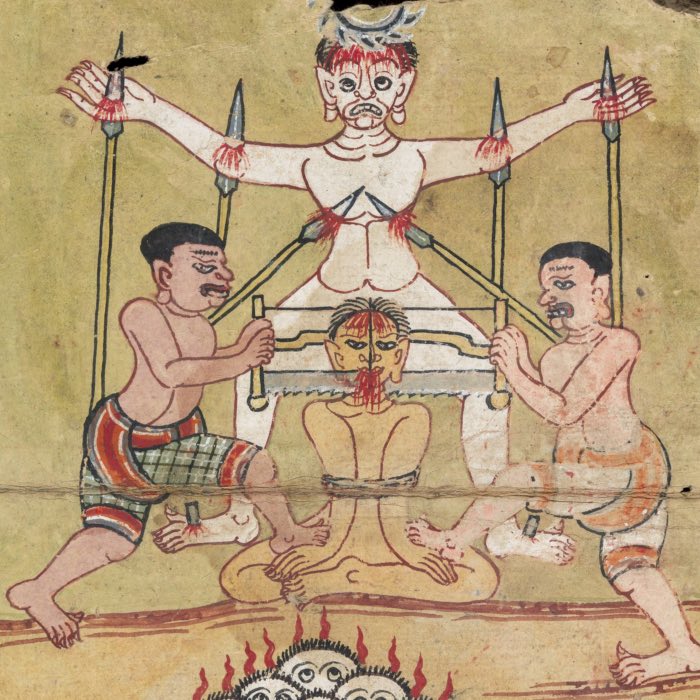

Treasury: Onthoofding van de H. Barbara (Beheading of St. Barbara), ca. 1520, Moderne polychromie.

Treasury: Onthoofding van de H. Barbara (Beheading of St. Barbara), ca. 1520, Moderne polychromie.

Treasury: Bust reliquary of bishops depicted as kings.

Treasury: Bust reliquary of bishops depicted as kings.

Treasury: Left figure of an ensemble showing Peter and Paul.

Treasury: Left figure of an ensemble showing Peter and Paul.

Treasury: Right figure of an ensemble showing Peter and Paul.

Treasury: Right figure of an ensemble showing Peter and Paul.

The cloister as contrast

Interestingly, the most immediate sense of calm I felt did not come from the main church space. It came from the cloister.

View into the cloister courtyard.

View into the cloister courtyard.

The enclosed courtyard, the plants, the fountain, the repetitive rhythm of columns and paths create a different kind of stillness. Nothing is highlighted. Nothing demands attention. You can walk without direction, or sit without purpose. The space does not instruct you. It simply allows you to remain.

A stone statue in the cloister courtyard.

A stone statue in the cloister courtyard.

Seen through a Buddhist lens, this contrast becomes especially clear. The basilica actively produces meaning. It directs attention, establishes hierarchy, and frames experience through emphasis and control. The visitor is guided toward specific focal points, both spatially and symbolically.

Cloister courtyard with a giant, old bell in one corner.

Cloister courtyard with a giant, old bell in one corner.

The cloister works differently. It does not demand interpretation or devotion. It offers space without instruction. From a Buddhist perspective, this difference matters: one environment encourages attachment to symbols and meanings, while the other allows perception to settle without insisting on interpretation. Meaning may arise there, but it is not imposed. And it may just as well dissolve again.

The central fountain in the cloister courtyard.

The central fountain in the cloister courtyard.

View into the cloister from one of the walkways.

View into the cloister from one of the walkways.

Another View into the cloister.

Another View into the cloister.

Use, belief, and persistence

Historically, the cult of Servatius was not only about devotion. It also stabilized power, attracted wealth, and anchored Maastricht within wider religious and political networks. In a city like Maastricht, that mattered twice: the cult anchored a religious identity, but it also anchored the city’s position in larger networks of prestige, traffic, and protection. Pilgrimage is devotion, but it is also infrastructure. The basilica benefited from this, and it still does. Sacredness here was never simply believed. It was learned and reinforced. Architecture directed movement, stories explained why certain places mattered, and institutional routines ensured that these patterns were repeated day after day. Over time, these elements aligned closely enough that the space felt self-evidently meaningful.

A wooden statue of Blessed Mary with Child.

A wooden statue of Blessed Mary with Child.

At the same time, reducing the site to strategy would miss something important. Whatever its political and economic roles, St. Servatius has also been a place where people came with grief, hope, fear, or exhaustion. They came to stand somewhere that felt ordered when their lives were not.

That function does not disappear just because belief systems change.

A wooden Pietà in a small side chapel of the basilica.

A wooden Pietà in a small side chapel of the basilica.

Detail view of the wooden Pietà.

Detail view of the wooden Pietà.

Conclusion: What remains

Visiting the Basilica of St. Servatius did not suddenly awake my belief in Christianity, nor was it meant to. What it did offer was a clearer view of how religious spaces work in general, and why they continue to matter even when their doctrinal foundations are contested, similarly to what we have explored in our previous post on Kloster Steinfeld.

The basilica is not sacred because something transcendent resides in its stones. It is sacred because its architecture, light, rhythm, and history consistently produce certain states of attention. It is sacred because it is. Over centuries, these effects were harnessed by institutions. But they were also used by individuals, often quietly and privately. That is why the place still works even if you do not share its original belief system. The basilica can be read as theology in stone, but it can also be used as a human tool: A machine for slowing down, for attention, for silence.

In that sense, St. Servatius remains relevant not as a monument to belief, but as a place where stillness, structure, and human vulnerability continue to meet. That, more than its art-historical importance, is what stayed with me I guess.

Earlier that day, our Maastricht trip had begun at the Bonnefanten Museum, located just across the river. The museum building, designed by Aldo Rossi, also plays with continuity and attention, but in a very different register. In the next post, I therefore reflect on how these two sites, despite their differences, could be interpreted as structurally related. Thus, stay tuned!

References and further reading

- Miriam Paloni, Maastricht. St. Servatius-Basilika, 2025, Schnell & Steiner, ISBN: 978-3795473761

- Aart J. J. Mekking, De Sint-Servaaskerk te Maastricht. Bijdragen tot de kennis van de symboliek en de geschiedenis van de bouwdelen en de bouwsculptuur tot ca. 1200, 1986, Walburg Pers, ISBN: 978-9060113394

- Elizabeth den Hartog, Romanesque Architecture and Sculpture in the Meuse Valley, 1992, Eisma, ISBN: 978-9074252041

- Elizabeth den Hartog, Romanesque Sculpture in Maastricht, 2002, Bonnefantenmuseum, ISBN: 978-9072251312

- Adrie Cense; Saskia Werner, De schatkamer van de Sint-Servaaskerk te Maastricht. Een keuze van de voorwerpen uit de schatkamer en hun functie, 1984, Walburg Pers, ISBN: 978-9060112786

- William M. Voelkle, The Stavelot Triptych: Mosan Art and the Legend of the True Cross, 1980, Oxford University Press / Pierpont Morgan Library, ISBN: 978-0195202250

- Benoît Van den Bossche (Hg.), L’art mosan. Liège et son pays à l’époque romane du XIe au XIIIe siècle, 2007, Éditions du Perron, ISBN: 978-2871142171

- Eric Fernie, Romanesque Architecture: The First Style of the European Age, 2014, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300203547

- Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity, 2014, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226175263

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe, 2011, Zone Books, ISBN: 978-1935408116

- Kim Knott, The Location of Religion: A Spatial Analysis, 2005, Acumen, ISBN: 978-1844657490

comments