Planetary aurorae

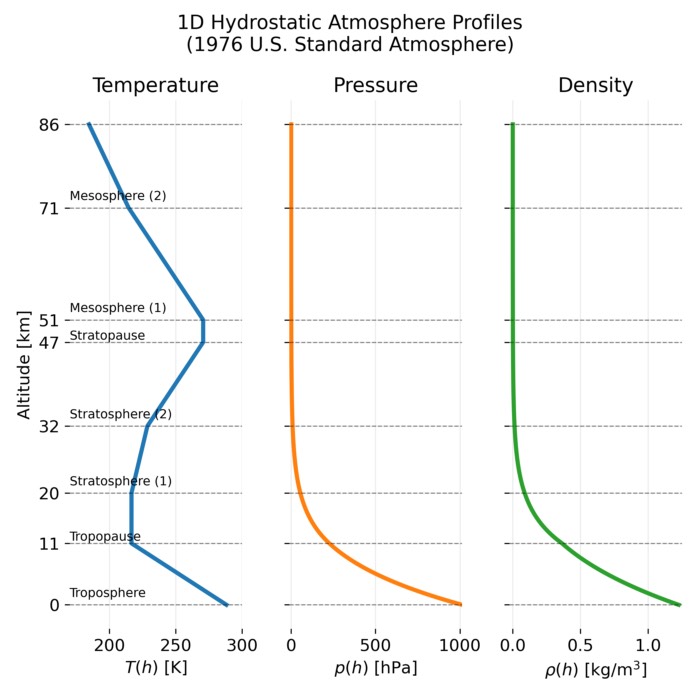

Planetary aurorae are among the most visually striking manifestations of space plasma physics. They appear as luminous structures in a planet’s upper atmosphere, typically concentrated around magnetic polar regions, and arise from the coupling between a magnetized plasma environment and an atmosphere capable of radiative emission. Although aurorae are most familiar from Earth, they are not a terrestrial peculiarity. Wherever a planetary body possesses an atmosphere and is exposed to energetic charged particles, auroral phenomena can emerge, with properties that encode the structure and dynamics of the surrounding magnetosphere.

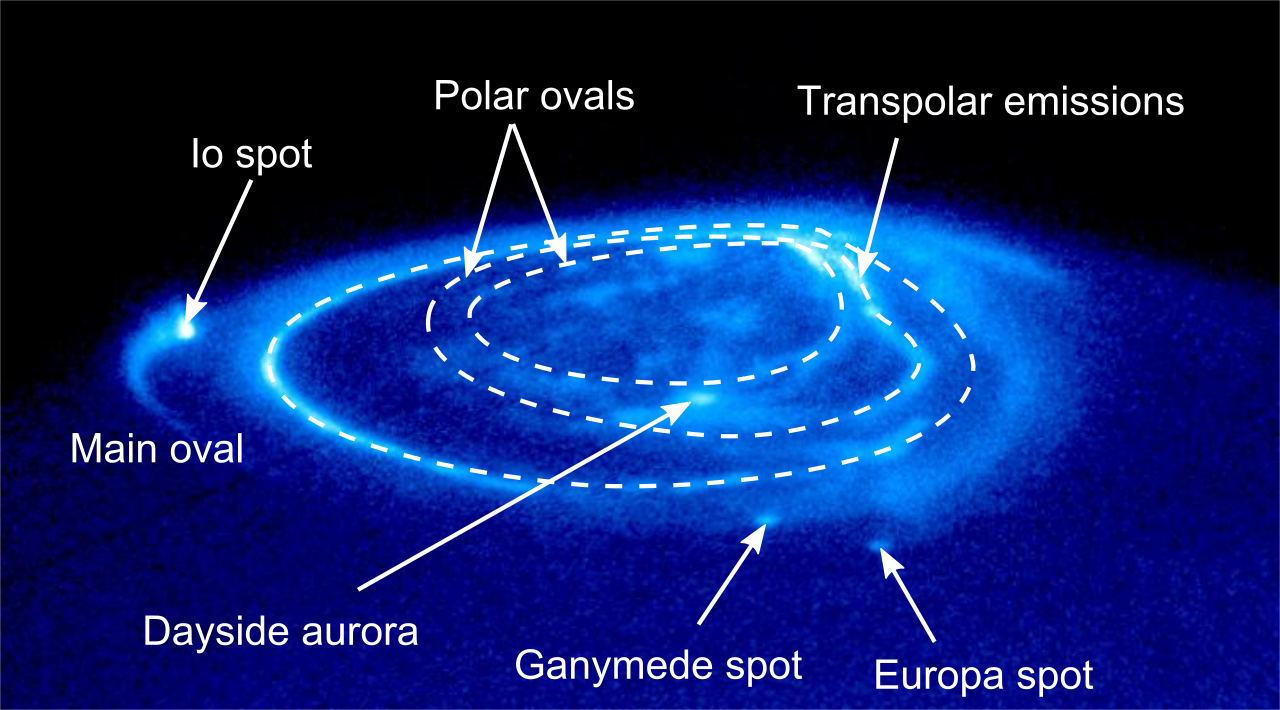

Jupiter’s aurorae observed by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in November 1998. The main auroral oval and polar ovals are marked with dash lines. Satellite spots and other features are also shown. Based on Palier, Laurent (2001). Aurorae are caused by the interaction of charged particles with a planet’s atmosphere, guided by its magnetic field. At Jupiter, aurorae are primarily driven by the planet’s rapid rotation and interactions with its moons, particularly Io, which injects plasma into the magnetosphere. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

From a scientific perspective, aurorae are not merely optical curiosities. They are macroscopic signatures of energy transport in space plasmas, linking the solar wind, magnetospheric circulation, field aligned currents, and atmospheric excitation into a single observable process. In this sense, aurorae function as remote diagnostics of plasma flows and electromagnetic energy conversion in planetary systems.

Aurora australis, seen on May 12, 2024 near Melbourne, Australia. Aurorae typically occur in oval patterns around the magnetic poles, where field lines connect to the magnetosphere. From Earth, we can observe aurorae in both hemispheres: the aurora borealis in the northern hemisphere and the aurora australis in the southern hemisphere. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

In this post, we give a brief overview of this lightning phenomenon, starting from its physical origin and mathematical description, before surveying auroral manifestations across the Solar System.

Physical origin and magnetospheric context

At their core, aurorae result from the precipitation of energetic charged particles into an atmosphere. These particles are typically electrons, sometimes ions, that are guided by a planet’s magnetic field toward regions where field lines intersect the upper atmosphere. The immediate cause of the emission is collisional excitation or ionization of atmospheric constituents, followed by radiative de excitation that produces light at characteristic wavelengths.

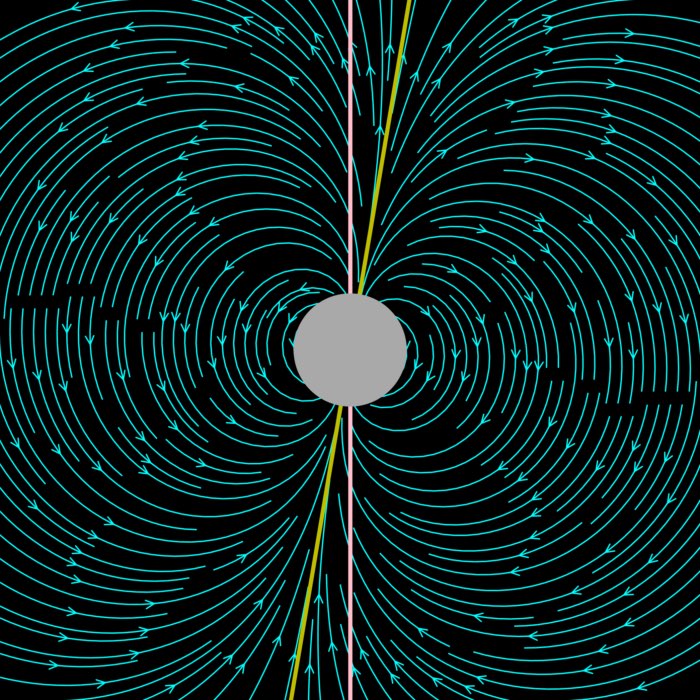

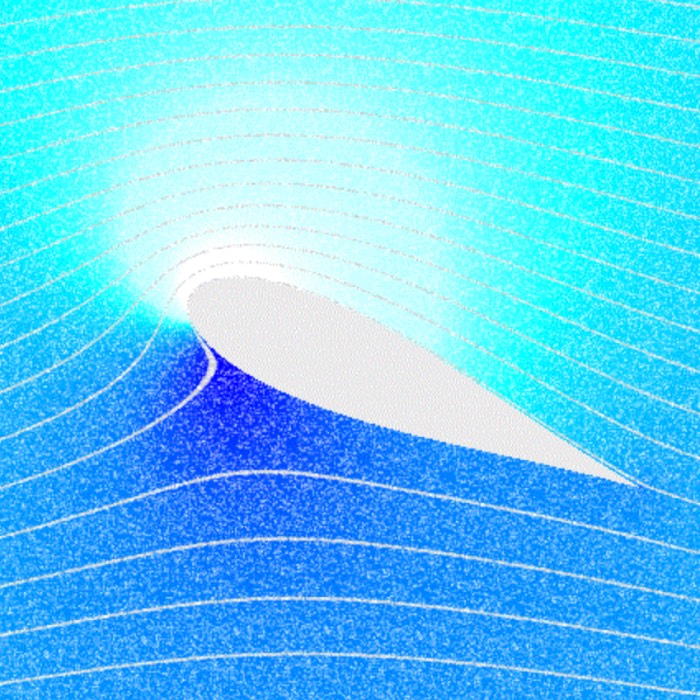

Schematic of Earth’s magnetosphere, with the solar wind flows from left to right. The magnetosphere is the region surrounding a planet where its magnetic field dominates the behavior of charged particles. The solar wind compresses the dayside magnetosphere and stretches the nightside into a long magnetotail. Key regions include the bow shock, magnetosheath, magnetopause, and radiation belts. Aurorae typically occur in oval patterns around the magnetic poles, where field lines connect to the magnetosphere. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

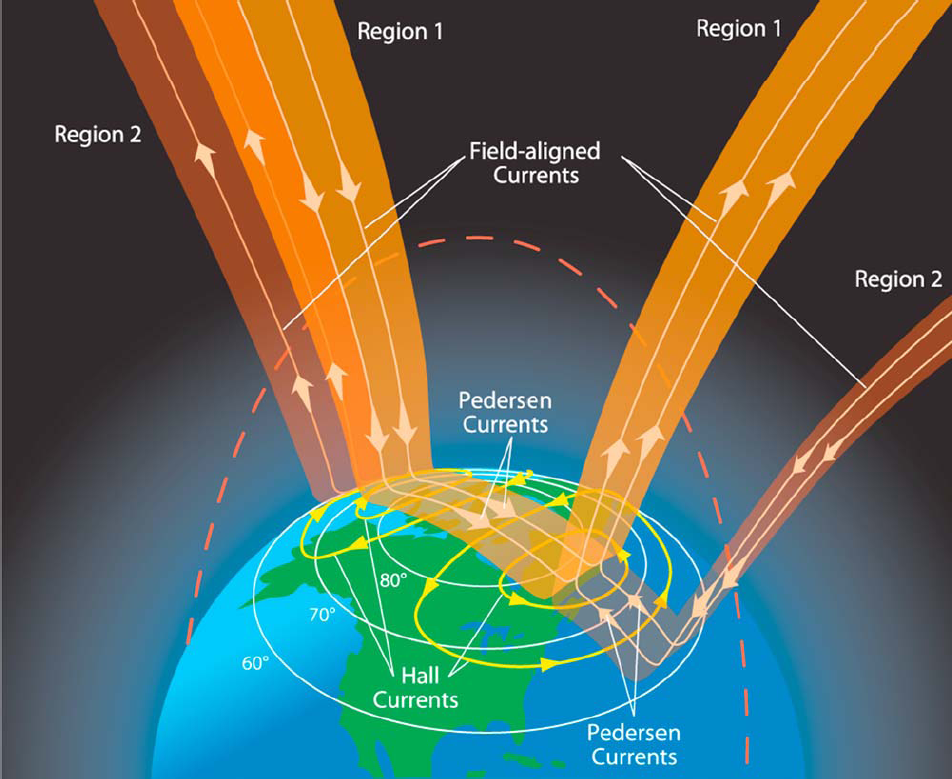

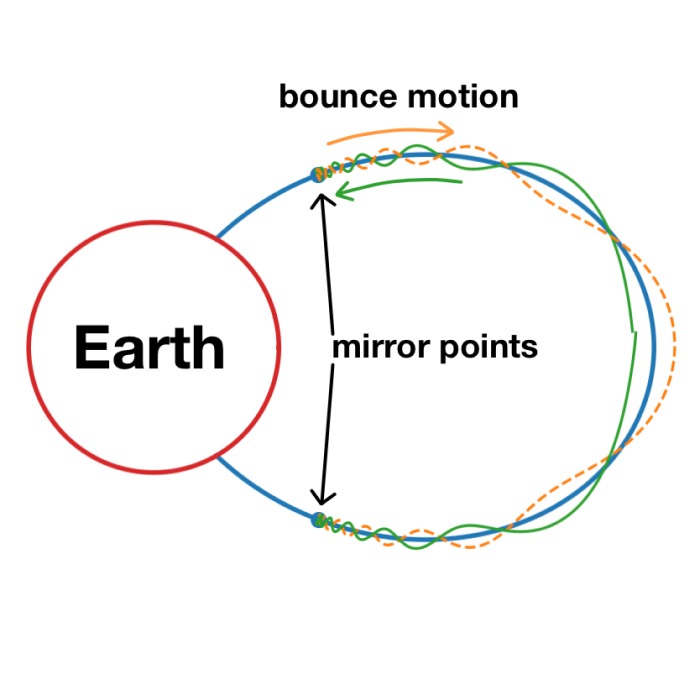

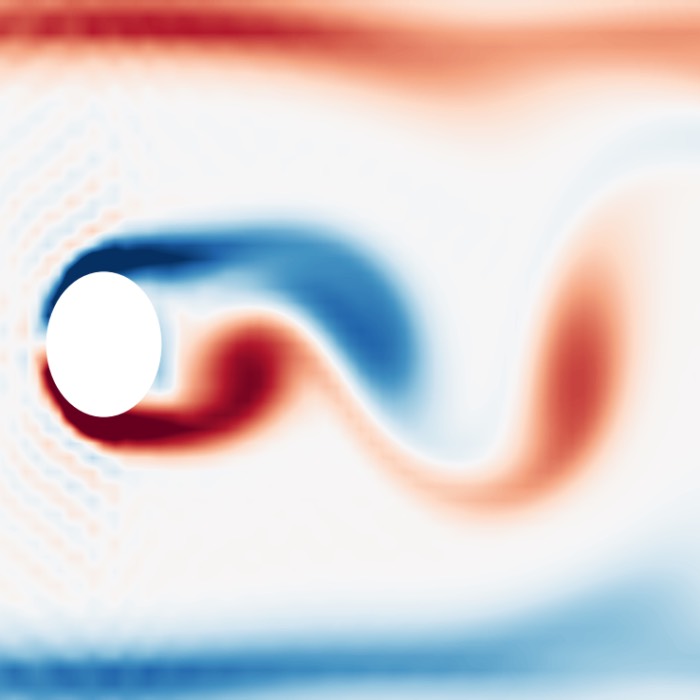

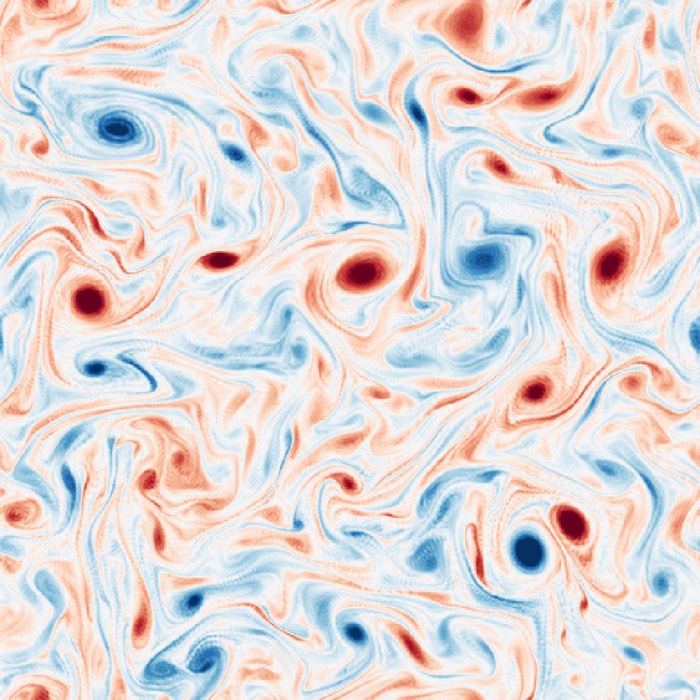

The deeper cause is magnetospheric. A magnetized planet embedded in a plasma flow develops a magnetosphere, a region where magnetic stresses dominate particle motion. Plasma transport within this region is inherently nonuniform. Gradients in plasma pressure, rotation driven shear, and interactions with the solar wind generate electric fields. These fields drive currents along magnetic field lines, often referred to as field aligned or Birkeland currents. Where these currents close through the ionosphere, particles are accelerated parallel to the magnetic field and precipitate downward, powering auroral emission.

Schematic of the Birkeland or Field-Aligned Currents and the ionospheric current systems they connect to, Pedersen and Hall currents. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2).

Aurorae therefore mark the end point of a global energy chain. Solar wind kinetic and magnetic energy, or internally generated rotational energy in rapidly rotating systems, is converted into electromagnetic energy, transported along magnetic field lines, and finally dissipated in the upper atmosphere as heat and light.

Mathematical description of auroral energy flow

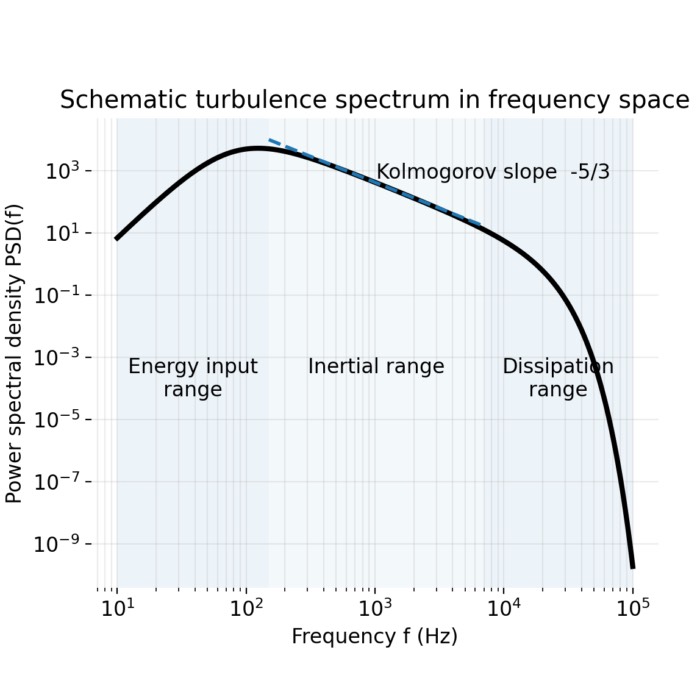

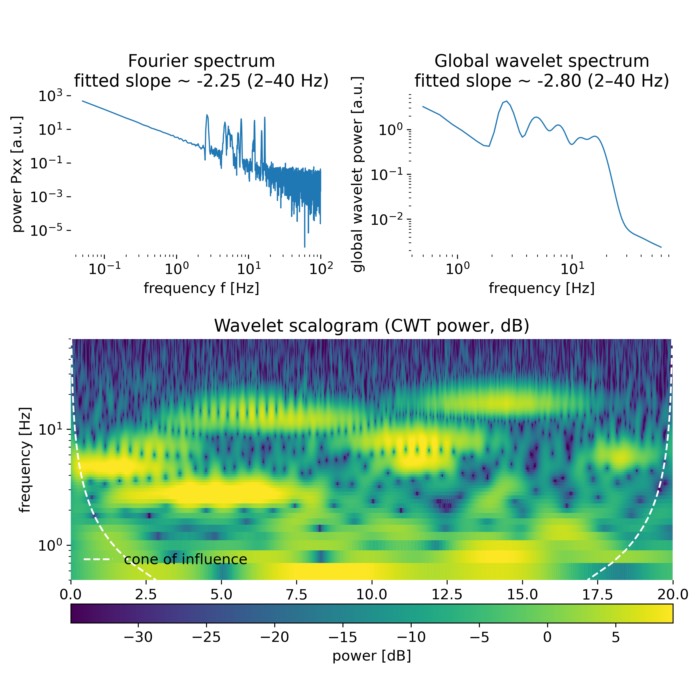

Aurorae can be described quantitatively as the terminal stage of an energy conversion chain that begins in the magnetospheric plasma and ends in atmospheric photon emission. The essential steps are electromagnetic energy transport, particle acceleration along magnetic field lines, collisional excitation of atmospheric species, and radiative decay. Each step can be formulated within standard plasma and radiation physics.

In a magnetized plasma, electromagnetic energy transport is described by the Poynting vector

\[\begin{align} \mathbf{S} = \frac{1}{\mu_0},\mathbf{E} \times \mathbf{B}, \end{align}\]where $\mathbf{E}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ denote the electric and magnetic fields and $\mu_0$ is the vacuum permeability. In auroral regions, a substantial component of $\mathbf{S}$ is directed along the magnetic field toward the ionosphere. This field aligned Poynting flux represents the rate at which electromagnetic energy is supplied from the magnetosphere into the auroral acceleration region.

The conversion of electromagnetic energy into particle energy is quantified by the energy balance relation

\[\begin{align} \nabla \cdot \mathbf{S} = -,\mathbf{j}\cdot\mathbf{E}, \end{align}\]where $\mathbf{j}$ is the current density. Regions with $\mathbf{j}\cdot\mathbf{E} > 0$ correspond to a net transfer of electromagnetic energy into particle kinetic energy, while negative values indicate the opposite. In auroral current systems, this term is dominated by parallel electric fields accelerating charged particles along magnetic field lines.

Magnetospheric convection, pressure gradients, and rotational shear drive perpendicular currents $\mathbf{j}_\perp$. Current continuity requires closure along magnetic field lines according to

\[\begin{align} \nabla_\perp \cdot \mathbf{j}*\perp + \frac{\partial j*\parallel}{\partial s} = 0, \end{align}\]where $j_\parallel$ is the field aligned current density and $s$ denotes distance along the magnetic field. When the ambient plasma cannot supply the required parallel current through adiabatic motion alone, a parallel electric field $E_\parallel$ develops. This field accelerates electrons downward toward the upper atmosphere and establishes the auroral precipitation.

The resulting precipitating electron energy flux into the atmosphere can be written as

\[\begin{align} \Phi_E = \int_0^\infty E,f(E),v(E),dE, \end{align}\]where $f(E)$ is the electron energy distribution function and $v(E)$ the corresponding particle velocity. Typical auroral electrons carry energies from a few hundred electronvolts up to several kiloelectronvolts, sufficient to drive excitation and ionization of atmospheric constituents.

As these energetic electrons penetrate the upper atmosphere, they undergo inelastic collisions with neutral and ionized species. These collisions populate excited electronic, vibrational, or rotational states. For a given excitation channel of species $s$, the local excitation rate per unit volume scales as

\[\begin{align} R = n_s \int \sigma(E),f(E),v(E),dE, \end{align}\]where $n_s$ is the number density of the target species and $\sigma(E)$ the relevant excitation cross section. This expression links the precipitating particle distribution directly to microscopic excitation processes.

Excited states subsequently relax, either radiatively or through non radiative channels such as collisional quenching or cascading into other states. For radiative decay from an upper state $u$ to a lower state $\ell$, each emitted photon carries a well defined quantum of energy

\[\begin{align} E_\gamma = h\nu_{u\ell} = \frac{hc}{\lambda_{u\ell}}, \end{align}\]where $h$ is Planck’s constant, $\nu_{u\ell}$ the transition frequency, and $\lambda_{u\ell}$ the corresponding wavelength. This relation provides the direct link between atomic and molecular transitions and the observed auroral spectrum.

The volumetric radiative power, or emissivity, associated with this transition is therefore

\[\begin{align} \epsilon_{u\ell} = h\nu_{u\ell},R_{u\ell}, \end{align}\]where $R_{u\ell}$ denotes the photon production rate per unit volume for that transition. Observable auroral intensities follow from integration of the emissivity along the line of sight,

\[\begin{align} I_{u\ell} = \int \epsilon_{u\ell}(s),ds, \end{align}\]up to geometric factors and, depending on wavelength, possible absorption.

Taken together, these relations close the auroral energy budget in a physically transparent way. Electromagnetic energy is transported from the magnetosphere by the Poynting flux, converted into kinetic energy of precipitating particles by parallel electric fields, transferred into internal energy of atmospheric species through collisional excitation, and finally released as discrete photons with energies $E = h\nu$. Aurorae thus provide a rare and direct observational link between global magnetospheric dynamics, plasma microphysics, and quantum mechanical emission processes.

Aurorae on other planetary bodies

Auroral phenomena have been observed on several planets in the Solar System, each exhibiting unique characteristics shaped by their magnetospheric environments, atmospheric compositions, and plasma sources.

Jupiter and its moons

Jupiter hosts the most powerful aurorae in the Solar System. Unlike Earth, Jupiter’s aurorae are primarily driven by internal rotation rather than the solar wind. The rapid rotation of the planet enforces near corotation of magnetospheric plasma, generating strong electric fields and currents. A defining feature is the auroral footprint of Io, whose volcanic activity supplies vast amounts of plasma to the magnetosphere. As Io moves through Jupiter’s magnetic field, it acts as an electrical generator, producing a current system that maps directly into bright, localized auroral spots.

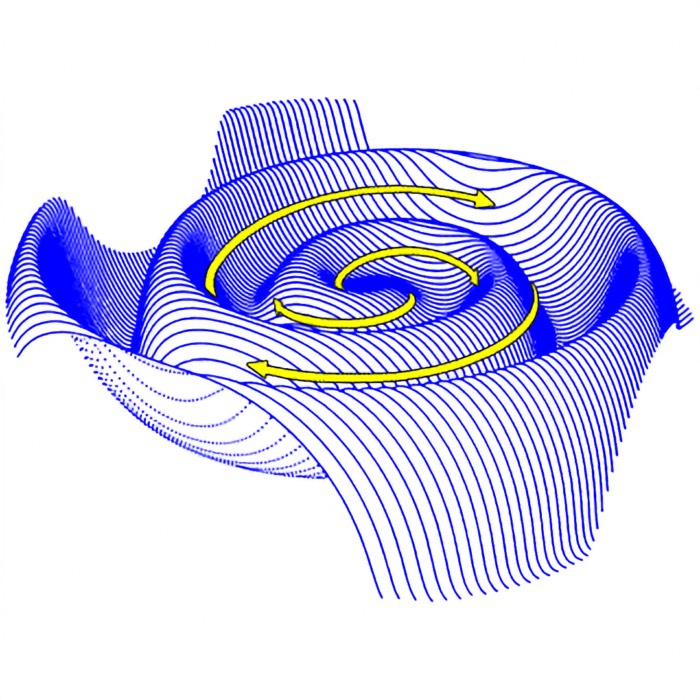

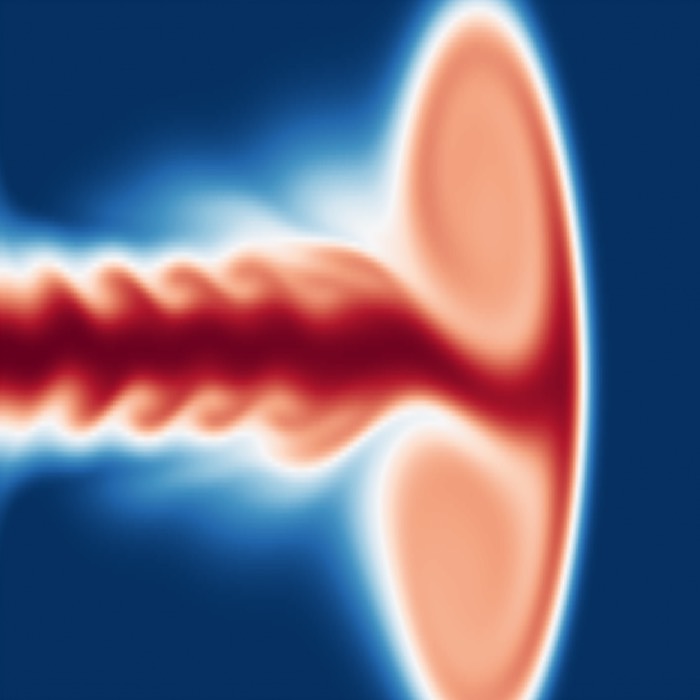

Jovian magnetosphere and plasma environment and flux. Overview of Jupiter’s magnetosphere in the vicinity of the Galilean satellites. H2+ pickup ions (blue) originate from Europa’s neutral toroidal cloud (brighter blue near Europa). Io and Europa contribute plasma pickup ions of different compositions to Jupiter’s magnetosphere. Alfvén wings connected to the moons due to their interaction with corotating plasma are also shown in gray. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Jovian aurorae are dominated by ultraviolet emission from molecular hydrogen and have been extensively observed by the Hubble Space Telescope and the Juno spacecraft. Their morphology reflects magnetospheric rotation, plasma injection events, and wave particle interactions on a global scale.

Left: Magnetic field of the Jovian satellite Ganymede, which is embedded into the magnetosphere of Jupiter. Closed field lines are marked with green color. Ganymede is, so far, the only moon in the solar system known to possess a substantial intrinsic magnetic field. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Aurorae on Ganymede. Due to the interaction with Jupiter’s magnetospheric plasma, Ganymede exhibits auroral emissions similar to those on Earth. From the shifting of the auroral belts, space physics is able to infer the presence of a subsurface ocean beneath Ganymede’s icy crust. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Saturn and its satellites

Saturn exhibits aurorae that share features with both Earth and Jupiter. Saturn’s magnetosphere is rotationally driven, but solar wind conditions play a stronger modulatory role than at Jupiter. Saturnian aurorae are highly dynamic, showing rapid brightening and motion in response to changes in solar wind pressure. Ultraviolet emissions from hydrogen again dominate.

Saturn with ultraviolet Aurorae, photographed in October 1997 by the Hubble Space Telescope’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) from a distance of 1.3 billion km. The aurora on Saturn is caused by the interaction of charged particles with the planet’s atmosphere, guided by its magnetic field. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0).

Interactions with Saturn’s moons, particularly Enceladus, influence auroral activity by supplying plasma through cryovolcanic outgassing. The Cassini mission provided a detailed view of these processes, linking auroral morphology to magnetospheric currents and plasma sources.

Sketch of Saturn’s magnetosphere. Saturn’s magnetosphere is shaped by the planet’s strong magnetic field and rapid rotation, as well as by interactions with the solar wind and its moons. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Uranus and Neptune

Aurorae on Uranus and Neptune are less well characterized, primarily due to observational challenges. Uranus is particularly intriguing because its magnetic field is strongly tilted and offset from the planet’s center. As a result, auroral regions sweep across a wide range of latitudes during a rotation. Ultraviolet aurorae on Uranus have been detected by Hubble, revealing a magnetosphere with extreme geometry and time dependent coupling to the solar wind.

Uranus’s upper atmosphere imaged by HST during the Outer Planet Atmosphere Legacy (OPAL) observing program. In 2011 the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) was able to spot faint auroras in its atmosphere. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0).

Neptune’s aurorae were first detected by Voyager 2 in extreme-ultraviolet and radio frequencies. Newer observations were performed by the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope, revealing transient auroral spots. Neptune’s aurorae are relatively faint and sporadic, reflecting the planet’s weaker magnetic field and more distant location from the Sun. However, much about Neptune’s auroral processes remains to be explored.

Left: A visible light image of Neptune taken by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). – Right: The HST image composited with a near-infrared image taken by the James Webb Telescope (JWT). As the aurorae cannot be observed in the visible band, their image in near-infrared has been rendered as shades of cyan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Mars and weakly magnetized bodies

Mars lacks a global intrinsic magnetic field, yet auroral emission has been observed. Mars possesses localized crustal magnetic fields that form mini magnetospheres. Energetic particles guided by these fields can precipitate into the atmosphere, producing discrete auroral features. In addition, diffuse aurorae driven directly by solar energetic particles have been detected. Observations by the MAVEN spacecraft have shown that aurorae on Mars are closely linked to atmospheric escape processes and solar wind interaction.

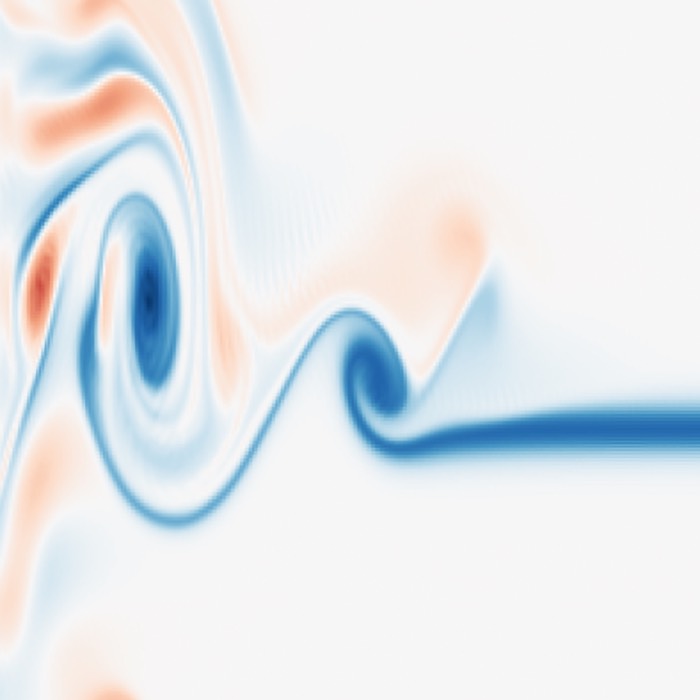

Comparison of normal and patchy proton aurora formation mechanisms at Mars. Top image shows the normal proton aurora formation mechanism first discovered in 2018. White lines show that solar wind protons traveling away from the Sun are normally swept around the planet by the Mars magnetosphere, and don’t directly interact with the atmosphere. When proton aurora occur, a small fraction of the solar wind collides with Mars hydrogen in the extended corona of the planet (shown in blue), and charge exchanges into neutral H atoms. These newly created H atoms are still travelling at the same speed, and are no longer sensitive to the magnetospheric forces that redirect protons around the planet. Instead, the energetic H atoms slam directly into the upper atmosphere of Mars and collide multiple times with the neutral atmosphere, resulting in auroral emission by the incident H atoms (purple). Because the solar wind and Mars corona are uniform across the planet, the aurora occurs everywhere on the planet’s day side with a uniform brightness. – Bottom image shows the newly discovered formation mechanism for patchy proton aurora. Green lines in the top image show that under normal conditions the solar wind magnetic field drapes nicely around the planet. By contrast, patchy proton aurora form during unusual circumstances when the solar wind magnetic field is aligned with the proton flow. Under such conditions the typical draped magnetic field configuration is replaced by a highly variable patchwork of plasma structures, and the solar wind is able to directly impact the planet’s upper atmosphere in specific locations that depend on the structure of the turbulence. When incoming solar wind protons collide with the neutral atmosphere, they can be neutralized and emit aurora in localized patches. During such times patchy proton aurora forms a map of the locations where solar wind plasma is directly impacting the planet. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Exoplanets

Auroral processes are also expected on magnetized exoplanets, particularly close in giant planets orbiting active stars. Although direct imaging is not yet feasible, theoretical models predict intense auroral radio and ultraviolet emission powered by strong stellar wind interaction. Detection of such emission would provide indirect evidence for planetary magnetic fields, a key factor in atmospheric retention and habitability. Observational efforts in low frequency radio astronomy aim to place constraints on these distant auroral systems.

Artist impression of the magnetic field around Tau Boötis b detected in 2020. Exoplanets interact with their stellar environment through plasma processes similar to those studied in our solar system. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Observational methods

Aurorae are observed across a broad range of wavelengths. Ground based optical imaging and spectroscopy remain central for Earth. Space based ultraviolet observations are essential for giant planets, where emissions occur predominantly outside the visible range. In situ particle and field measurements by spacecraft allow the direct sampling of precipitating particles and electromagnetic energy flux, enabling quantitative closure of auroral energy budgets.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST), as seen from the space shuttle Discovery during its second servicing mission. Space based observatories like HST have been crucial for studying planetary aurorae, particularly in the ultraviolet range where many auroral emissions occur and where Earth’s atmosphere is opaque. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 2.0).

Radio observations probe related processes, particularly electron cyclotron maser emission associated with auroral acceleration regions. Together, imaging, spectroscopy, and in situ diagnostics form a multi scale observational framework that links microscopic particle dynamics to global magnetospheric structure.

Conclusion

Planetary aurorae are a universal consequence of plasma interaction with planetary atmospheres in the presence of magnetic fields. They represent a natural laboratory for studying energy conversion in space plasmas, from large scale electromagnetic transport down to atomic excitation. Differences between planets highlight the diversity of magnetospheric drivers, ranging from solar wind forcing to internal rotation and moon driven current systems.

From Earth to the outer planets and potentially beyond the Solar System, aurorae provide a direct and observable connection between plasma physics and planetary environments. Their study continues to refine our understanding of magnetospheres, atmospheric evolution, and the fundamental physics of charged particles in cosmic magnetic fields.

Update: This post was originally drafted in 2020 and archived during the migration of this website to Jekyll and Markdown. In January 2026, I substantially revised and expanded the content and decided to re-release it in an updated and technically consistent form, while keeping its original chronological context.

References and further reading

- Wolfgang Baumjohann and Rudolf A. Treumann, Basic Space Plasma Physics, 1997, Imperial College Press, ISBN: 1-86094-079-X

- Treumann, R. A., Baumjohann, W., Advanced Space Plasma Physics, 1997, Imperial College Press, ISBN: 978-1-86094-026-2

- Bagenal, F., Dowling, T. E., McKinnon, W. B. (eds.), Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521035453

- Dougherty, M. K., Esposito, L. W., Krimigis, S. M., Gombosi, T. I., Amstrong, T. P., Arridge, C. S., Khurana, K. K., Krimigis, S. M., Krupp, N., Persoon, A. M., & Thomsen, M., Saturn from Cassini-Huygens, 2009, Springer, ISBN: 978-1402092169

- Chamberlain, J. W., Hunten, D. M., Theory of Planetary Atmospheres, 1987, Academic Press, ISBN: 978-0121672515

- Cowley, S. W. H., Bunce, E. J., O’Rourke, J. M., A simple quantitative model of plasma flows and currents in Saturn’s polar ionosphere, 2004, Journal of Geophysical Research, 109(A5), doi: 10.1029/2003JA010375ꜛ

- Cravens, T. E., Physics of Solar System Plasmas, 1997, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521611947

- Gérard, J. C., et al., Characteristics of Saturn’s FUV aurora observed with the Hubble Space Telescope, 2004, Journal of Geophysical Research, 109(A9), doi: 10.1029/2004JA010513ꜛ

- Borovsky, J. E., Auroral Arc Thicknesses as Predicted by Various Theories, 1993, Journal of Geophysical Research, 98(A4), 6101–6113, doi: 10.1029/92JA02242ꜛ

- Goertz, C. K., Io’s interaction with the plasma torus, 1980, Journal of Geophysical Research, 85(A6), 2949–2956, doi: 10.1029/JA085iA06p02949ꜛ

- Feldman, Paul D.; McGrath, Melissa A.; et al., HST/STIS Ultraviolet Imaging of Polar Aurora on Ganymede, 2000, The Astrophysical Journal. 535 (2): 1085–1090, doi: 10.1086/308889ꜛ

- Saur, Joachim; Duling, Stefan; Roth, Lorenz; Jia, Xianzhe; Strobel, Darrell F.; Feldman, Paul D.; Christensen, Ulrich R.; Retherford, Kurt D.; McGrath, Melissa A.; Musacchio, Fabrizio; Wennmacher, Alexandre; Neubauer, Fritz M.; Simon, Sven; Hartkorn, Oliver, 2015, The search for a subsurface ocean in Ganymede with Hubble Space Telescope observations of its auroral ovals, Journal of Geophysical Research, Volume 120, 3, p. 1715–1737, doi: 10.1002/2014JA020778

- Hill, T. W., Inertial limit on corotation, 1979, Journal of Geophysical Research, 84(A11), 6554–6558, doi: 10.1029/JA084iA11p06554ꜛ

- Knight, S., Parallel electric fields, 1973, Planetary and Space Science, 21(5), 741–750, doi: 10.1016/0032-0633(73)90093-7ꜛ

- Lysak, R. L., Lotko, W., On the kinetic dispersion relation for shear Alfvén waves, 1996, Journal of Geophysical Research, 101(A3), 5085–5094, doi: 10.1029/95JA03712ꜛ

- Milan, S. E., Grocott, A., Hubert, B., Relationship between solar wind parameters and auroral forms, 2010, Space Science Reviews, 151, 209–244, doi: 10.1029/2011JA017082ꜛ

- Rees, M. H., Physics and Chemistry of the Upper Atmosphere, 1989, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521368483

- Southwood, D. J., Kivelson, M. G., Magnetospheric interchange instability, 1987, Journal of Geophysical Research, 92(A1), 109–116, doi: 10.1029/JA092iA01p00109ꜛ

- Waite, J. H., et al., Electron precipitation and related auroral emissions at Jupiter, 2001, Journal of Geophysical Research, 106(A12), 26279–26294

- Zarka, P., Auroral radio emissions at the outer planets, 1998, Journal of Geophysical Research, 103(E9), 20159–20194, doi: 10.1029/98JE01323ꜛ

- Joachim Saur, Sascha Janser, Anne Schreiner, George Clark, Barry H. Mauk, Peter Kollmann, Robert W. Ebert, Frederic Allegrini, Jamey R. Szalay, Stavros Kotsiaros, Wave-particle interaction of Alfvén waves in Jupiter’s magnetosphere: Auroral and magnetospheric particle acceleration, 2018, Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 123, 9560–9573. doi: 10.1029/2018JA025948ꜛ

- Dols, V., P. A. Delamere, and F. Bagenal, A multispecies chemistry model of Io’s local interaction with the Plasma Torus, 2008, J. Geophys. Res., 113, A09208, doi: 10.1029/2007JA012805

comments