Reflections on joining Bluesky: Opportunities and risks for the scientific community

Over the past two weeks, I have taken a closer look at Bluesky, exploring its features and dynamics through the lens of my own experience within the neuroscience community. So far, my impressions have been mixed: while some aspects of Bluesky are genuinely promising, others evoke certain concerns about the future of scientific communities on digital platforms. In this post, I would like to share a personal reflection on this recent shift, situating it within the broader context of academic social media migration.

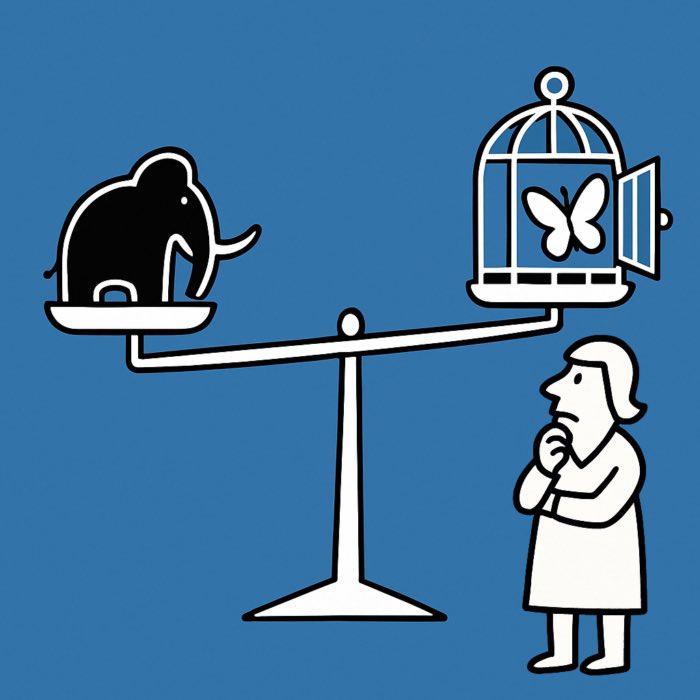

Reflections on joining Bluesky: Opportunities and risks for the scientific community. The scientific community is once again shifting platforms — seeking visibility, stability, and trust in uncertain digital environments. Bluesky offers new momentum and technical promise, but questions around decentralization, moderation, and long-term sustainability remain. Between Mastodon’s ideals and Bluesky’s usability, we are faced with a complex landscape of compromises. Image generated by DALL-E.

Background: From Twitter to Mastodon to Bluesky

The first major turning point came with the acquisition of Twitter by Elon Musk in 2022, followed by the abrupt dismissal of over a thousand employees and a marked decline in content moderation. These changes led to a sharp increase in hate speech, disinformation, and the proliferation of extremist accounts. Faced with this environment, I, like many others, decided to leave Twitter and joined Mastodon. The open-source and decentralized nature of Mastodon seemed to offer a safeguard against similar scenarios, fostering a strong sense of community and agency. Importantly, it did not feel like handing over one’s data to a major tech corporation free of charge. During this first migration wave, numerous scientists also moved to Mastodon, and an active, interdisciplinary science community quickly emerged there.

However, over time, activity on Mastodon — at least within my own scientific community — declined steadily. Posts and interactions became noticeably less frequent. That does not mean that activity dropped to zero. Today, there is still a considerable number of active users — some of whom have Mastodon as their only social media presence, others who use it alongside other platforms. However, the initial wave of enthusiasm has faded. When I recently screened the list of people I follow, I found many accounts that have not posted anything in the last one or two years, even though the same people were quite active on alternative platforms.

Discovering Bluesky: A new migration

A few weeks ago, I created a Bluesky account after my PI mentioned that much of the neuroscience community had shifted there. To my surprise, I found not only the people I had previously followed on Mastodon, but also a much larger cohort of scientists who had stayed on Twitter during the first migration wave and had not joined Mastodon. It appears that there was a significant migration wave from Twitter (and partially from Mastodon) to Bluesky about 6–8 months ago, which I had not followed in real time. While I do not know the precise reasons, it is plausible that Elon Musk’s ongoing political involvement, his public support for Donald Trump, and policy decisions affecting scientific and governmental institutions contributed to this second exodus. Also, around the same time, Bluesky switched from invitation-only access to open registration, making it easier for new users to join.

In the last weeks, I have reconnected with many familiar faces from previous platforms. Once again, I have the sensation — one I first felt when joining Twitter when I started my postdoc and later when moving to Mastodon — of participating in an ongoing, global scientific conference. The constant stream of new publications, lively discussions about research and methodology, and the sharing of professional challenges evoke the productive atmosphere of conference discussion, coffee break talks and poster sessions. In my view, Bluesky is currently experiencing its own moment of vibrancy. I expect that the current level of activity will subside somewhat, just as it did on Twitter and Mastodon, but for now, my community seems to have found a new home — and a new toy to play with.

What does Bluesky do differently?

So, what makes Bluesky different from Mastodon? In my view, there are several key features that contribute to its appeal, especially for scientific communities.

First, Bluesky’s user interface could be perceived as more intuitive and user-friendly than Mastodon’s. The design is clean, and actually replicates the familiar Twitter layout, which makes it easy for new users to navigate.

Second, Bluesky makes onboarding and community-building noticeably easier than Mastodon. While Mastodon requires users to select a server and navigate the complexities of decentralized instances, Bluesky’s main platform (bsky.socialꜛ) serves as a default entry point, simplifying the registration process. This reduces the initial barrier for newcomers, allowing them to focus on content rather than technical details.

Third, Bluesky improves on Mastodon in terms of discovering and connecting with people outside one’s own server. On Mastodon, viewing the full profile and post history of a user on a different instance is still cumbersome; often, it requires opening their profile URL in a web browser or using third-party apps with additional features. In contrast, Bluesky makes the entire public profile and posting history of any user easily accessible, facilitating more informed decisions about whom to follow or connect with.

Another notable feature driving Bluesky’s rapid community growth is the proliferation of so-called “starter packs”: user-curated lists that aggregate accounts by topic or field (e.g., computational neuroscience or general neuroscience). With a single click, one can follow a relevant community, reconstructing the network of contacts that might have taken months to build on Mastodon, where similar initiatives relied on manually shared spreadsheets or GitHub repositories.

What I miss from Mastodon

Despite these advantages, there are features of Mastodon that I miss. The ability to follow hashtags is particularly valuable for tracking topics across the entire platform, regardless of who is posting. The local focus on specialized servers or instances also creates a distinct community feel — one is more inclined to support their own server, even financially. Local feeds display posts from all members of an instance, whether or not you follow them, fostering engagement with new voices in the field.

Additionally, Mastodon is deeply rooted in an open-source and community-driven development ethos. Users can directly contribute ideas, report issues, or even participate in development through open platforms such as GitHub. This grassroots character fosters a sense of shared ownership and trust.

Moreover, moderation on Mastodon is handled by instance administrators — often individuals or collectives from within the community — who operate transparently and are usually accessible. This decentralized and local approach to moderation offers a clarity and accountability that Bluesky, with its more centralized moderation structure, currently lacks.

From a technical standpoint, Bluesky still lacks certain practical features: there is no option to schedule posts or to edit them after publishing. This may change in the future, but for now, it is a limitation that can be inconvenient for users who are accustomed to these functionalities on other platforms.

On the risks: Will Bluesky repeat Twitter’s trajectory?

My greatest concern is that Bluesky could ultimately follow the same path as Twitter. What guarantees are there that the platform will not be acquired, monetized, or filled with advertisements? Who actually moderates Bluesky servers at present? On Mastodon, moderation is handled by the instance operators — often ordinary users — making for a more transparent and approachable system than the opaque management of large tech companies.

Bluesky is built on the AT Protocolꜛ, which is designed to enable true decentralization: users and communities should, in principle, be able to operate their own independent servers (or “personal data servers”), with portable identities and content. In its ideal implementation, this would prevent any single entity from exercising absolute control, and would make a Musk-style takeover or forced monetization considerably more difficult. However, as of now, the majority of users are concentrated on the main bsky.socialꜛ server, and the broader decentralization ecosystem remains in early stages. It is thus an open question whether Bluesky’s architecture is robust enough to prevent the pitfalls that befell Twitter. Much depends on how quickly and widely genuine decentralization is adopted in practice.

Conclusion

At present, Bluesky offers a promising environment for academic exchange, with several advantages in usability and community formation over Mastodon. However, the future trajectory of the platform is uncertain, and concerns about moderation, commercial interests, and long-term sustainability remain. For now, I will continue to use both Mastodon and Bluesky in parallel. Both platforms still host active scientific communities, often with some degree of overlap, and maintaining a presence on each increases resilience against unforeseen changes. If you are in the same situation, I recommend exploring Bluesky while also staying engaged with Mastodon. Each platform has its strengths and weaknesses, and the best approach may be to leverage the unique opportunities they each provide. The landscape of academic social media continues to evolve, and, in my view, flexibility is essential.

comments