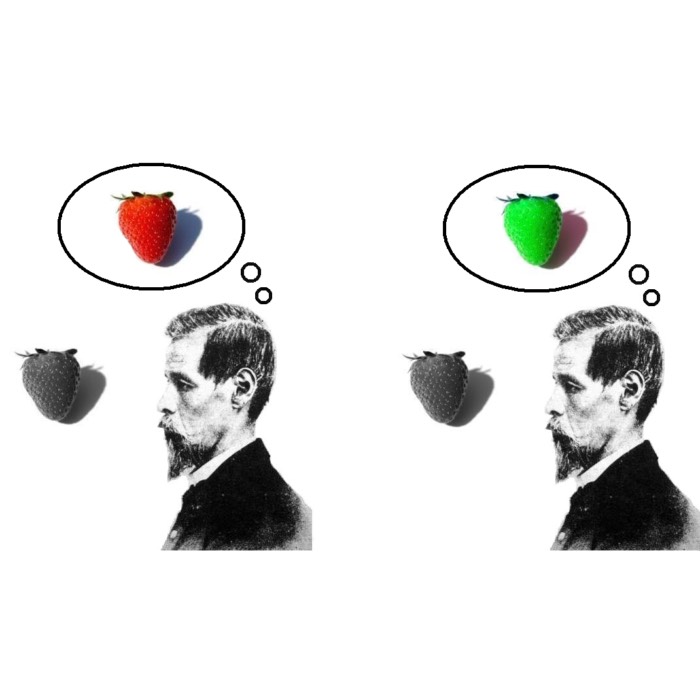

Understanding Dukkha: Beyond mere suffering

Among the many concepts that shape Buddhist thought, none is more central — or more widely misunderstood — than dukkha. Often rendered in English as “suffering”, the term is richer and more complex than this translation suggests. In Western contexts, “suffering” typically evokes extreme experiences — grief, illness, violence, or despair. But in the context of early Buddhist philosophy, dukkha points to something far more pervasive: a structural flaw in the fabric of existence itself. It names not just acute pain, but the persistent discomfort, instability, and incompleteness of all conditioned experience.

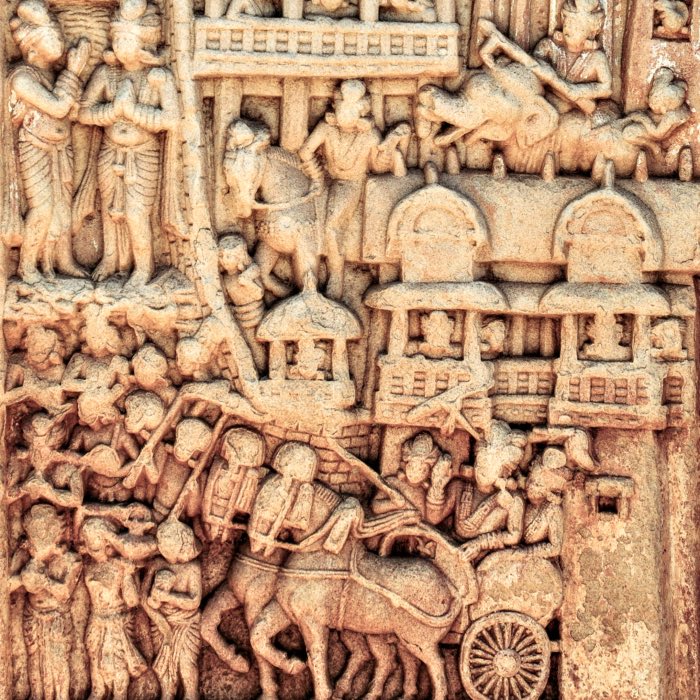

Bhāvacakra – or Wheel of Life – a symbolic representation of the cycle of existence in Buddhism, saṃsāra. The wheel is held by Yama, the god of death, and is divided into six realms of existence, each representing different states of being. The outer ring depicts the twelve links of dependent origination, illustrating the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. In Buddhist thought, all beings are trapped in this cycle due to ignorance and craving. And the core characteristic of saṃsāra is dukkha. Everything depicted in the wheel is thought to be either a form of dukkha or a condition that leads to dukkha. Source: Raimond Klavinsꜛ hosted on Unsplashꜛ (license: Unsplash licenseꜛ)

The significance of dukkha cannot be overstated. It is the starting point of the Four Noble Truths, the very first teaching attributed to Siddhartha Gautama after his awakening. And it is not presented as a passing feature of life, but as an essential insight into the human condition: a recognition that as long as beings live within the confines of impermanence, craving, and delusion, suffering will follow. To understand dukkha is therefore to understand the problem Buddhism seeks to solve.

This post offers a close philosophical reading of dukkha — its meaning, structure, and existential implications. We explore the term’s conceptual layers, its relation to impermanence and attachment, and its foundational place within the Buddha’s vision of liberation. In doing so, we follow the structure and interpretation developed in Sebastian Gäb’s Die Philosophie des Buddha – Eine Einführung (2024), a book that I recently read and which provides both clarity and depth to one of the most profound insights in Buddhist thought.

The meaning and scope of dukkha

The word dukkha (Pāli; Sanskrit: duḥkha) originates from ancient Indian languages and conveys a sense of discomfort, imbalance, or friction — a fitting image for the Buddhist understanding of dukkha as the pervasive unease that arises from the impermanent and conditioned nature of existence.

In everyday discourse, dukkha is often equated with suffering, but this translation is inadequate in capturing its full depth. While physical pain, emotional distress, and loss are obvious forms of dukkha, the concept extends to more subtle forms, including the existential dissatisfaction that arises even in moments of happiness. The impermanence (anicca) of all things ensures that pleasure is fleeting, and attachment (upādāna) to transient states inevitably leads to disappointment. Thus, dukkha is not simply about suffering in the conventional sense but refers to the fundamental inability of conditioned existence to provide lasting satisfaction.

In fact, the common translation of dukkha as “suffering” can be misleading. In modern usage, “suffering” often implies intense physical or emotional pain. But dukkha includes every shade of discomfort, from the most trivial irritation to the most harrowing agony — from a broken coffee cup to being burned alive. What matters is not the intensity of the experience, but the fact that it fails to meet an ideal of happiness, ease, or satisfaction. Even something as subtle as wishing a situation were different already qualifies as dukkha. Much of it goes unnoticed in daily life, yet it quietly permeates all conditioned existence.

The dimensions of dukkha

Traditionally, Buddhist teachings describe dukkha as manifesting in three distinct ways, each highlighting a particular mode through which suffering pervades our lives. These are not merely abstract classifications; they offer two complementary perspectives — one doctrinal and structural, the other psychological and experiential. Together, they reveal how suffering operates not just in moments of obvious distress, but across the entire spectrum of lived experience.

-

Suffering as pain or ordinary suffering — dukkha-dukkha

Doctrinally, this refers to the most direct and recognizable forms of suffering: physical pain, illness, aging, death, as well as mental anguish such as grief, fear, or despair. These are the raw, tangible hardships that remind us of our vulnerability.

Experientially, this includes any situation where we are confronted with the discomforts of bodily existence and emotional turmoil — from acute sickness to heartbreak. It is the suffering we all intuitively recognize as suffering. -

Suffering due to change — vipariṇāma-dukkha

Doctrinally, this arises from the transience of all phenomena. Even pleasurable experiences become painful when they pass. The moment we become attached to something pleasant, its loss becomes inevitable — and with that, suffering arises.

Experientially, it appears as frustration, sadness, or longing whenever something enjoyable ends — a vacation, a relationship, even a beautiful day. The pain lies not in the thing itself, but in its impermanence, which contradicts our deep-seated wish for lasting happiness. -

Suffering due to conditioned existence — saṅkhāra-dukkha

Doctrinally, this is the most subtle and pervasive form. It refers to the unsatisfactoriness inherent in all conditioned phenomena — that is, anything composed, impermanent, and dependent. This suffering is bound up with the insight into non-self (anattā), revealing that even in the absence of acute pain or change, life is marked by a fundamental incompleteness.

Experientially, it is the quiet unease or restlessness that persists even when things seem to be going well — the sense that something is always slightly off. It stems from our futile attempt to find lasting identity and fulfillment in processes (the five khandhas) that are, by their nature, impermanent and contingent.

These three forms are best understood not as mutually exclusive categories, but as layers. Some are immediately felt, others are so subtle they escape ordinary awareness. Taken together, they form a comprehensive map of suffering — from overt pain to the most refined forms of existential dissatisfaction. To understand dukkha in its fullness, all three levels must be acknowledged.

The existential basis of dukkha

Dukkha is not a random or occasional misfortune that befalls us from time to time. It is embedded in the existential structure of reality itself. In its natural state, all existence tends toward suffering because everything is marked by anicca, impermanence. Even happiness cannot endure; it inevitably fades, leaving behind a sense of loss or lack. Thus, we are unavoidably returned to dukkha, again and again. The very conditions of life — its instability, its uncontrollability — ensure that dukkha is the default mode of existence.

This means that even when existence is temporarily free from suffering, it tends to relapse into it. Suffering can never be completely and permanently suppressed. While we may delay or mitigate it — by investing energy into health, comfort, or security — such relief is always provisional. As soon as circumstances shift, the natural condition of suffering reasserts itself. And since reality is marked by anicca, constant change, there is ultimately no enduring state that can escape dukkha for long. It is not a matter of individual misfortune but a structural consequence of conditioned existence.

Why impermanence leads to suffering

Everything that exists is impermanent and subject to decay, and thus even good things inevitably come to an end. In addition to the direct, intrinsic forms of suffering, there is also suffering that arises precisely because of impermanence. This kind of suffering springs from the finitude of things we consider desirable. Craving (taṇhā) emerges as a thirst for permanence — the wish to hold onto what brings us pleasure and security. When we attach ourselves to such things, we hope that by finally securing what we desire, lasting happiness will follow. But this hope is an illusion. We cannot possess anything permanently, because nothing endures. The moment we obtain something, it has already begun to change — and so have we. From one moment to the next, these changes may be imperceptible, but over time they accumulate and eventually become undeniable. We age every day, and though the change is subtle, two decades make it unmistakable. A world in which all our wishes could be permanently fulfilled would require a world without change — but if impermanence defines the nature of reality, then such a world is a contradiction in terms.

Dukkha is the universal mark of existence. It arises from the interplay of two structural forces: taṇhā, the craving that compels beings to grasp for satisfaction, and anicca, the impermanence that guarantees all conditions will change and pass away. As long as we crave permanence in an impermanent world, we suffer.

This tension does not merely lie in the fact that things change, but in the way sentient beings relate to change. Unawakened minds cling instinctively to what is fleeting, resisting the flow of impermanence. They long for continuity where none can be found, and thus encounter disappointment, frustration, and suffering. Since all things are conditioned and lack a stable essence (anattā), no object or experience can offer the lasting fulfillment they seek.

The inevitability of suffering

Suffering arises from the collision between us — finite, conditioned beings — and the impermanence of reality. As long as beings like us exist in a world like this, suffering is inevitable. This is no accidental outcome but a structural necessity: dukkha arises inevitably from the nature of existence itself. No strategy or effort can fully prevent it, because it is built into the structural mismatch between our conditioned being and a world that constantly changes.

The core of Siddhartha Gautama’s diagnosis can be reformulated as a logical structure:

- If sentient beings desire something impermanent, dukkha arises.

- Everything that exists is necessarily impermanent.

- Every sentient being that has not attained liberation necessarily desires something.

- Therefore: If sentient beings exist, dukkha necessarily arises.

Premise (1) has already been explored in the previous sections: suffering emerges whenever desires remain unfulfilled — and this is inevitable when both the objects of desire and the desiring beings themselves are impermanent. In such conditions, no lasting state of satisfaction can ever be reached.

Premise (2) expresses a metaphysical insight: impermanence is not an accident of our world but an intrinsic property of reality. As everything arises in dependence upon other things, nothing possesses enduring essence or self-sufficiency. All phenomena are conditioned and therefore unstable.

Premise (3) requires further qualification. More precisely, it applies to all unliberated sentient beings, who by their very condition are subject to craving and attachment. In Siddhartha’s teaching, this condition is not final: it stems from a fundamental misperception of self and reality — a state of ignorance (avijjā). Through awakening, this delusion can be overcome, and with it, the thirst (taṇhā) that generates suffering can cease.

The structure of this premise is still compelling. Desiring arises from the presence of needs. Needs, in turn, reflect a perceived or actual lack. A being that needs sleep, food, warmth, or safety seeks to eliminate a deficit. And finite beings — which rely on external conditions for continued existence — necessarily encounter such needs. A living being cannot generate the conditions for life on its own: it must draw them from its environment. Even a basic requirement such as food cannot be summoned from within but must be acquired. This existential dependency guarantees the continual arising of lack — and with it, of suffering.

Suffering and the role of attachment

Does all suffering involve attachment? According to Buddhist analysis, suffering — in the full sense of dukkha — only applies to sentient beings, those capable of feeling and awareness. An earthquake, no matter how catastrophic, does not suffer; it is simply earth in motion. Suffering arises only when a conscious being reacts to such an event — when I do not want to be injured, or I fear for the lives of those I love, or I lament the loss of my home. In each of these cases, attachment is at work: attachment to my body, to others, or to possessions.

Even seemingly straightforward examples like physical pain involve this dynamic. Pain, as a sensory event, is not identical to suffering. Pain becomes suffering when the mind responds with resistance — when taṇhā arises and says, “I don’t want this.” This is the ordinary, instinctive reaction to pain. But it is not inevitable. For instance, a masochist may experience physical pain without suffering from it. Conversely, even pleasurable sensations can be experienced as suffering if they are unwanted.

You can explore this distinction experientially in everyday situations that involve discomfort. For example, the next time you sit in an awkward posture and begin to feel some physical tension or dull pain, observe what happens in your mind. Try to focus on the sensation itself — its intensity, texture, and location — without immediately reacting to it with aversion. Notice whether the urge to shift or escape it comes from the sensation itself or from your resistance to it. This practice helps clarify that suffering is not simply the presence of pain, but our relationship to it.

Dukkha and the Four Noble Truths

Isn’t all of this a terribly pessimistic view of the world? The Buddha would respond that it is not pessimistic but realistic. To reject the idea that all conditioned existence involves suffering is to remain caught in illusion — to refuse to see reality as it is. Denying dukkha is itself another form of craving, the desire for a life free from suffering. We say, “Surely life can’t be so bleak,” and in doing so try to argue the suffering away. But according to the Buddha, only when we acknowledge suffering — instead of covering it with comforting stories — can we hope to transcend it.

Moreover, the truth of dukkha is only the first of four truths. The Buddha does not say, “All existence is suffering — and that’s the end of it.” That would indeed be a bleak philosophy. What follows is crucial: there is a way out of suffering. The Four Noble Truths do not stop at diagnosis but point to a path of liberation. In this sense, Buddhism is deeply optimistic: it promises that the suffering of existence can be overcome, and this possibility is open to all — to every sentient being.

The Buddha’s first teaching after his enlightenment was the Four Noble Truths, in which dukkha takes center stage as the primary problem to be understood and overcome. These truths offer both a diagnosis of the human condition and a prescription for liberation:

- The truth of dukkha (dukkha-sacca) – The acknowledgment that suffering is an inherent part of life.

- The truth of the origin of dukkha (samudaya-sacca) – Identifying craving (tanhā) and attachment (upādāna) as the primary causes of suffering.

- The truth of the cessation of dukkha (nirodha-sacca) – Asserting that suffering can be extinguished through the cessation of craving.

- The truth of the path to the cessation of dukkha (magga-sacca) – Providing the Eightfold Path as the method for overcoming suffering.

Understanding dukkha is not meant to instill pessimism but to encourage insight into the nature of reality. By fully comprehending dukkha, one gains the wisdom to abandon the attachments and illusions that perpetuate suffering.

The impersonal nature of suffering

No one is to blame for suffering. Dukkha is not the result of a conscious decision made by some higher being. Of course, there are many instances in which specific forms of suffering are caused by intentional acts of harm committed by individuals. But in a fundamental sense, the existence of suffering itself is not anyone’s fault. In Buddhism, this means that the classic theodicy question — “Why does a benevolent and omnipotent God allow suffering?” — simply does not arise. The Buddha’s answer is clear: there is no reason. The suffering of conditioned beings is not a punishment, nor is it a test, nor does it serve a moral or metaphysical purpose. It is simply the way conditioned existence works.

This has profound consequences. It means that there is no higher power who can or will lift suffering from us — no divine intervention to remove the burden of dukkha. Only we ourselves can free ourselves from it, by understanding its nature and following the path of insight and practice. Liberation is not given — it must be realized.

Conclusion

The concept of dukkha stands as one of the most radical and illuminating insights of Siddhartha Gautama’s teaching. It redefines suffering not as a temporary misfortune or moral punishment, but as an inescapable feature of conditioned existence. By tracing the roots of dukkha to impermanence (anicca), craving (taṇhā), and the illusion of a permanent self (anattā), Buddhism offers a diagnosis that is at once metaphysical, psychological, and existential.

Throughout this article, we have seen that dukkha manifests in multiple forms — from obvious pain and loss to subtle unease and existential restlessness. It arises not only because life includes suffering, but because beings cling to what inevitably changes and resist what they cannot control. Buddhism differs here sharply from many Western approaches, which often seek to eliminate suffering through external conditions — technological progress, political reform, or therapeutic intervention. In contrast, the Buddhist path begins by recognizing that suffering is not merely situational but structural. The goal is not to redesign the world, but to transform our relationship to it.

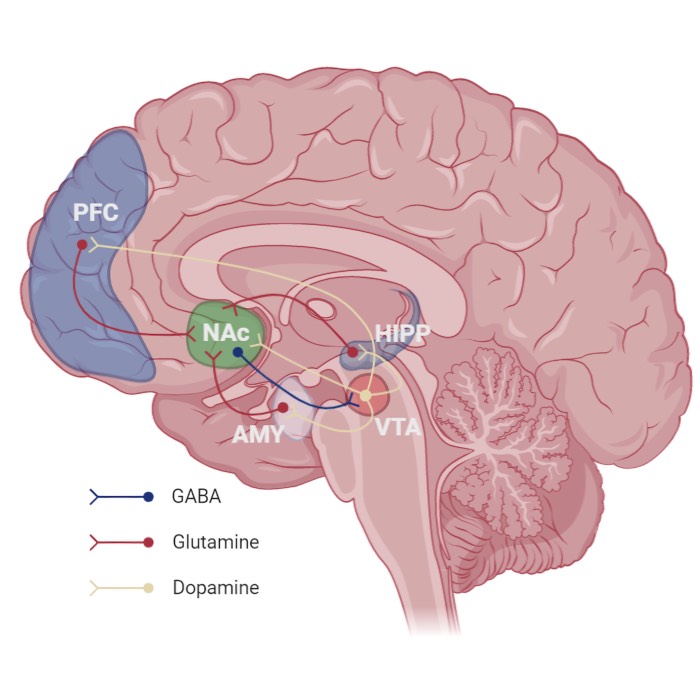

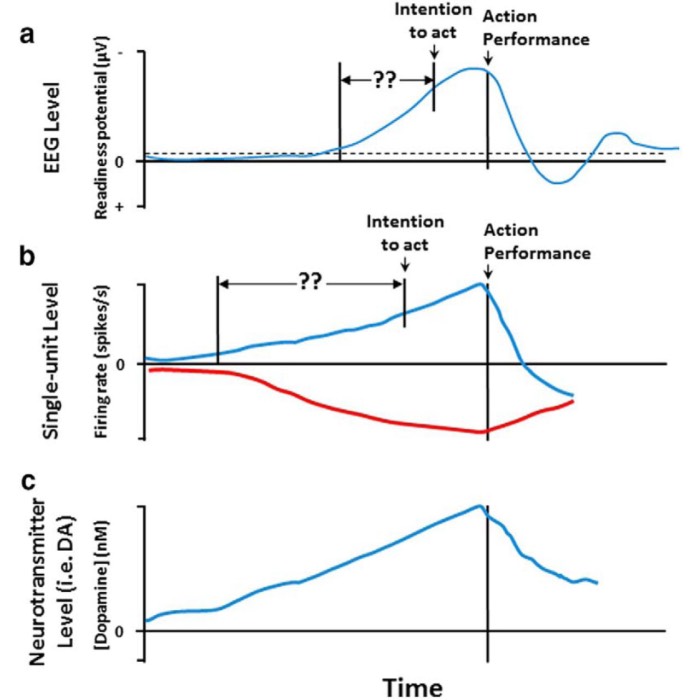

This perspective has profound resonance with developments in modern psychology and neuroscience. The link between craving, aversion, and dissatisfaction is now well documented in affective neuroscience, and mindfulness-based therapies draw heavily on Buddhist techniques to cultivate awareness, reduce reactivity, and enhance emotional resilience. Yet unlike much of modern psychology, early Buddhism does not aim merely to reduce stress or restore functionality. It seeks to fundamentally reorient one’s experience of the world, breaking the cycle of craving and suffering at its root.

What makes the Buddhist view so powerful is not its pessimism, but its honesty. To face dukkha without denial is not to give in to despair, but to step onto the path of wisdom. Rather than offering consolation through hope, Buddhism offers liberation through insight. And in this lies its enduring value: not in promising happiness as an escape from suffering, but in teaching us how to live within reality as it truly is — without illusion, without attachment, and ultimately, without dukkha.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments