The Northern and Southern Schools of early Chinese Chán Buddhism

The division between the so-called Northern and Southern Schools of Chán Buddhism represents one of the most formative moments in the development of Chinese Zen. Though often presented as a sharp doctrinal conflict between gradual and sudden enlightenment, this dichotomy has been the subject of both historical exaggeration and modern scholarly reevaluation. Still, the polemics and personalities involved in this split, particularly those surrounding Shenxiu and Huineng (638–713), had profound consequences for the trajectory of Zen thought and institutions in East Asia.

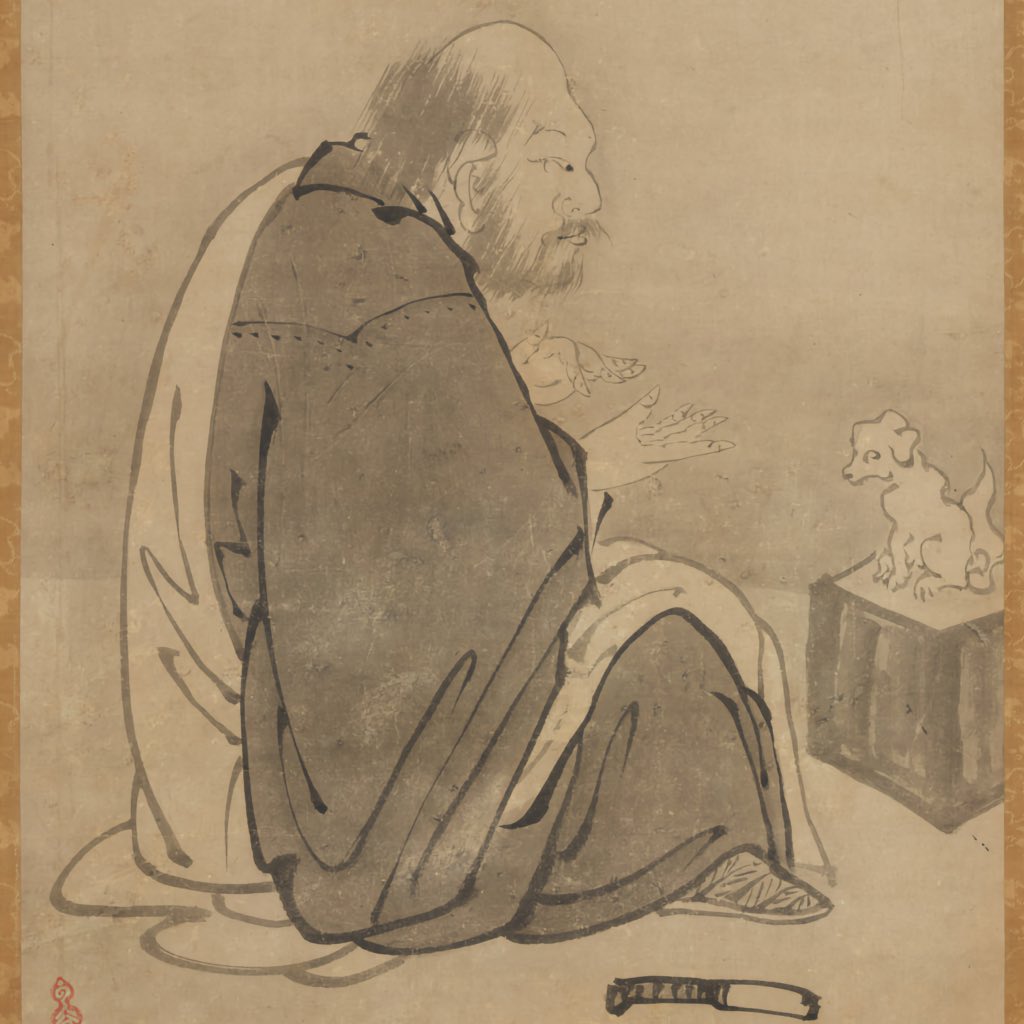

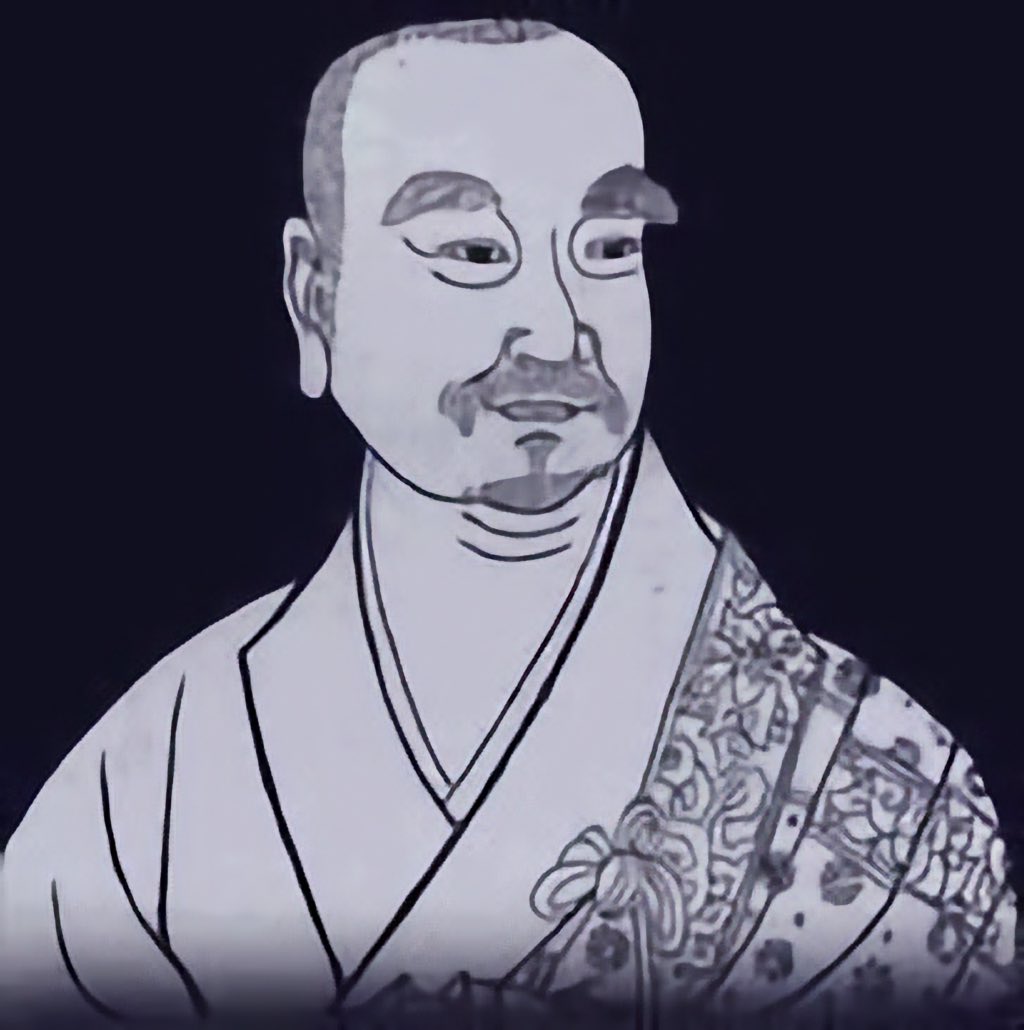

Huineng (638–713) (left; excerpt from a tryptich by Unkoku Tōeki, 1600-1644) and Shenxiu (right). Both figures are pivotal in the history of Chán Buddhism, representing the two main schools that emerged in the Tang dynasty (618-907). The Northern School, associated with Shenxiu, emphasized gradual enlightenment and systematic practice, while the Southern School, represented by Huineng, advocated for sudden enlightenment and direct experience. However, beyond this traditionally simplistic dichotomy, the historical and doctrinal realities of these schools are more complex. The Northern School’s influence in courtly and monastic circles was substantial, and its teachings were not merely a precursor to the Southern School but part of a rich tapestry of early Chán thought. Source left: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain), source right: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In this post, we explore the historical roots of this division, the philosophical and pedagogical positions attributed to each school, and the broader significance of the dispute. While the Southern School would eventually come to define the orthodox self-understanding of Chán, the Northern School’s influence in courtly and monastic circles at the time was substantial and deserves closer attention.

Historical context and figures

The split between the Northern and Southern Schools emerged in the late 7th and early 8th centuries, following the death of the Fifth Patriarch Hongren (601–674). The terms “Northern” and “Southern” were initially geographic: Shenxiu (606?–706), based in the north and active in the imperial court, came to be associated with the so-called Northern School, while Huineng (638–713) (638–713), active in the southern regions of China, particularly in Guangdong and Jiangxi, became recognized as the patriarch of what would later be called the Southern School.

It is important to note, however, that the term “school” in this context did not initially refer to formalized institutions or organized lineages. Rather, it reflected emerging doctrinal orientations and styles of practice that were retrospectively categorized and contrasted, particularly by later advocates of the Southern School. These groupings represented teaching currents or rhetorical identities more than clearly defined organizations.

This division, however, was not merely geographic. It gradually took on doctrinal and institutional significance. While Shenxiu’s position at the capital helped solidify his prominence and established a structured lineage of teachers and disciples centered around methodical practice, Huineng (638–713)’s lineage, preserved through oral transmission and compiled texts like the Platform Sūtra, emphasized a more radical, immediate form of insight. These two lines of development solidified into distinct schools primarily through later polemical writings and sectarian efforts to define orthodoxy within Chán Buddhism.

Shenxiu gained considerable recognition during his lifetime and was invited to the imperial court, where he was treated with great reverence. His teachings emphasized a methodical approach to practice, often interpreted as “gradual enlightenment.” In contrast, Huineng (638–713), who initially remained unknown and worked outside elite monastic circles, became retroactively elevated through the Platform Sūtra, which cast his approach as emphasizing “sudden enlightenment.”

The dichotomy was sharpened by polemical texts and sectarian disputes, most notably those produced by disciples of Huineng (638–713) seeking to legitimize his lineage and discredit Shenxiu’s. The influential Platform Sūtra and other writings such as Shenhui’s debates framed the Southern School as the authentic transmission of Bodhidharma’s radical insight.

Doctrinal differences

Gradual versus sudden enlightenment

The most frequently cited difference between the two schools concerns the nature of awakening. The Northern School is often portrayed as advocating a gradual path of purification, using meditation and moral discipline to progressively cleanse the mind of defilements. This view likens enlightenment to polishing a mirror: one must diligently remove obscurations before the original clarity of mind can be revealed.

The Southern School, in contrast, maintains that the mind is originally pure and that realization of this purity can occur instantly, in a single moment of direct insight. Enlightenment, therefore, is not the product of cumulative effort, but a shift in perception — the cessation of deluded thinking and the immediate recognition of one’s Buddha-nature.

Practice and pedagogy

These philosophical differences were reflected in pedagogical styles. The Northern School favored systematic meditation techniques, scriptural study, and ethical cultivation. It placed value on the gradual refinement of consciousness and often drew on mainstream Mahāyāna sources.

The Southern School de-emphasized formal techniques in favor of spontaneous insight, direct transmission, and unconventional teaching methods such as paradox, silence, and rhetorical challenge. It aligned closely with the teachings of the Platform Sūtra, which warned against attachment to form, concept, or ritual.

Political and institutional dynamics

The Northern School enjoyed the favor of the Tang court, particularly Empress Wu Zetian, who admired Shenxiu and promoted his teachings. This support gave the Northern School significant institutional clout during its peak.

In contrast, the Southern School operated outside state-supported monastic structures for much of its early history. However, by the mid-8th century, particularly following the influence of Huineng (638–713)’s disciples like Heze Shenhui, the Southern School gained prominence. Shenhui’s public debates and political maneuvering successfully repositioned Huineng’s lineage as the legitimate successor of Bodhidharma and the true heart of Zen.

Reevaluation and legacy

Modern scholarship has increasingly questioned the sharpness of the doctrinal division between the Northern and Southern Schools, noting that the contrast between gradual and sudden enlightenment may have been exaggerated for polemical or political purposes. While traditional accounts frame the schools as radically opposed, with one emphasizing systematic purification and the other sudden realization, historical evidence suggests a more nuanced overlap in practice and teaching. Both schools operated within the same Mahāyāna framework, drew on similar texts, and addressed a shared concern with direct experience of the Buddha-nature. The dualistic portrayal of their divergence may thus reveal more about the rhetorical strategies of lineage-building and institutional competition than about deep philosophical incompatibility.

Nonetheless, the Southern School’s framing of sudden enlightenment became canonized as the defining characteristic of Zen, shaping later traditions in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. The later Five Houses (Guiyang, Caodong, Linji, Fayan, and Yunmen), which developed during the Tang and early Song dynasties, all arose from within the Southern School’s doctrinal orbit and trace their heritage through Huineng (638–713)’s lineage. These Houses represent internal diversification of the Southern tradition, rather than a continuation of the earlier Northern School, which had faded by that time. The Northern School, while eventually eclipsed, contributed significantly to the monastic culture and doctrinal scaffolding of early Chán.

Conclusion

The emergence of the Northern and Southern Schools of Chán Buddhism reflects not only differing interpretations of practice and awakening but also the dynamic and contested development of Zen’s early identity. While the Northern School, championed by Shenxiu, gained imperial favor and advocated a methodical, gradual path to enlightenment, the Southern School, associated with Huineng (638–713), advanced a more radical vision: that awakening is sudden, immediate, and available to all.

This doctrinal split has long been interpreted as a polarizing conflict between two opposing camps. However, modern scholarship has revealed this to be, at least in part, a product of later polemics — particularly by figures like Shenhui who sought to assert Huineng (638–713)’s legitimacy and displace Shenxiu’s influence. The real divergence may have been less stark in actual practice than it appears in the texts. Both schools shared foundational Mahāyāna concepts and were ultimately committed to the direct realization of Buddha-nature.

Nevertheless, the success of the Southern School in positioning itself as the true heir of Bodhidharma’s transmission had enduring effects. Its emphasis on sudden enlightenment, direct experience, and anti-ritualism became defining features of Zen as it developed in East Asia. Over time, this orientation gave rise to the Five Houses of Chán, which expanded and diversified the Southern tradition while maintaining its core principles. The Northern School, while it did not survive as a lasting lineage, contributed significantly to early Chán’s institutional structure and its synthesis of meditative and scholastic elements.

In the end, the legacy of the Northern and Southern Schools is not merely one of doctrinal difference but of the fluid, rhetorical, and historical processes through which Buddhist traditions evolve. Their encounter shaped the identity of Zen and highlighted the tension — still relevant today — between form and formlessness, method and immediacy, gradual cultivation and sudden insight.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments