Time and timelessness in Zen

Time, for most of us, is something linear. It ticks forward in steady increments, separating past, present, and future. We plan, remember, and worry according to this unfolding sequence. But Zen offers a radically different view. Rather than seeing time as something external that we move through, Zen invites us to experience time as something that arises with our very being. Time is not “out there” — it is “this”, here and now. In this post, we explore how Zen, particularly through the teachings of Eihei Dōgen and the practice of zazen, reconfigures our understanding of time. We’ll look at the distinction between conventional clock-time and the timeless immediacy of the present, the meaning of Dōgen’s concept of uji (“being-time”), and the implications of Zen’s temporal view for practice and life.

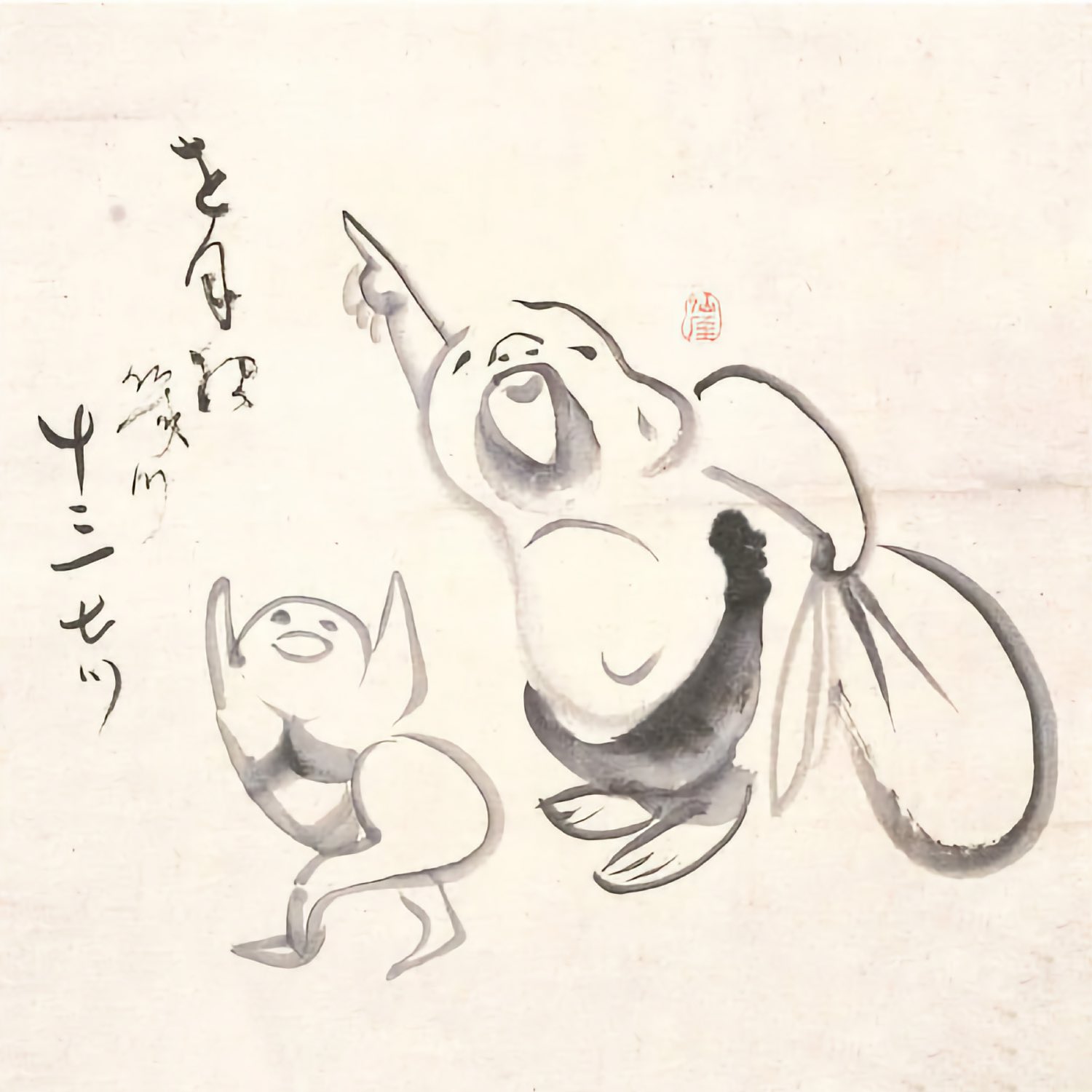

Which month is it?, Sengai, before 1838. “Which month is it?”, a question that is no question at all. In this playful zenga (Zen painting), Sengai confronts the absurdity of temporal fixation through humor: the figures gesture skyward, puzzled or proclaiming, yet the real teaching lies in their spontaneity. Time, like self, dissolves in the immediacy of the moment. There is no ‘right’ season, only ‘suchness’, right here, now. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain; modified)

The illusion of linear time

Zen challenges the habitual view that time consists of a flowing sequence of moments. This linear conception, which dominates much of modern thought and daily life, underlies many forms of existential suffering: regret over the past, anxiety about the future, and the habitual postponement of life into a later, imagined moment. It encourages the view that life is always elsewhere, something to be achieved or fixed, rather than something fully available now.

In contrast, Zen redirects our attention to the only time we ever truly inhabit: the present moment. The past exists only as memory, the future only as projection, both arising within present consciousness. Rather than denying time, Zen urges us to investigate how time actually presents itself in lived experience. What we discover is not a sequence of moments moving from past to future, but a single, unfolding presence, what Dōgen called “being-time”.

Dōgen’s Uji (有時): Being-Time

One of the most profound contributions to Zen’s philosophy of time is Dōgen’s notion of uji (有時), often translated as “being-time”. In his essay of the same name, Dōgen collapses the boundary between existence and temporality. Every being is time, and every moment is a full manifestation of that being-time.

This means that your current state of being, your posture, your breath, your awareness, is not something within time but is itself an expression of time. Dōgen writes, “Time is already just for a time, being is all time. Every being is time.” There is no abstract container of time in which things unfold. Rather, each phenomenon is its own moment of time. A tree is not something that grows in time; it is time as tree – time as sprouting, time as branching, time as withering. And the same is true for you: your sitting, breathing, thinking. All of it is the unfolding of time that is you.

Zazen and the collapse of time

In zazen, seated meditation, practitioners are encouraged to let go of all striving, goals, and notions of past and future. One simply sits. In doing so, something curious happens: the sense of linear time begins to dissolve. What remains is a kind of still, open presence, not static, but vividly alive.

This is not about entering a trance or losing consciousness. Rather, it’s a subtle shift in perception, where each moment stands fully on its own, not as a stepping stone to the next, but as its own beginning and end. In this sense, zazen enacts Dōgen’s uji. Practice is not a way to accumulate merit or progress through time toward enlightenment; it is awakening itself.

Everyday implications: Timelessness in action

Zen’s perspective on time has far-reaching implications beyond the meditation cushion. It invites us to reconsider how we engage with our daily lives. Can we wash the dishes, answer an email, or walk through a room as if these actions were not leading somewhere else, but complete in themselves?

Dōgen often spoke of how “practice and realization are not two.” This means that how we live each moment is our realization. Time is not a means to an end. The end is already here, expressed in each act of attention, each breath, each step.

This view also cultivates a kind of reverence for the ordinary. If every moment is whole and irreducible, then there is nothing “mere” about making tea, folding laundry, or watching the rain. Each is the whole of time expressing itself as this activity, right now.

Beyond permanence and impermanence

Zen does not propose timelessness as an escape from impermanence, nor as a fixed eternal realm. Instead, it sees time as the dance of impermanence itself, always changing, but never outside the present. In this sense, timelessness is not the negation of time but its full embodiment.

To live in Zen is not to transcend time but to fully inhabit it, moment by moment. We are not waiting to arrive; we have never left. The path is not a road stretching into the future, but the ground beneath our feet.

Conclusion

Zen’s understanding of time dissolves the habitual sense of linear progression and replaces it with a radically present-centered view. Rather than seeing time as something external that flows from past to future, Zen reveals time as the unfolding of being itself. This is most deeply expressed in Dōgen’s concept of uji, “being-time,” which shows that every phenomenon is not in time but is time. Every moment — every breath, every step, every word — is complete in itself and is the full manifestation of life.

Zazen embodies this insight through practice. Seated meditation removes the distractions of goal-seeking and narrative thinking, revealing the immediacy of each moment. In this way, zazen is not preparation for awakening but awakening expressed in sitting itself. One does not meditate to reach a better state later; one meditates to be completely present with what is. And this applies equally to everyday life — Zen practice invites us to recognize the sacredness of the ordinary, to meet every act as the full expression of reality.

Critically, this temporal view distances Zen from both a purely nihilistic impermanence and from notions of fixed eternity. It avoids both the linear striving for future enlightenment and the reification of timeless truth as something static. Instead, it affirms that awakening is always right now — dynamic, alive, and inextricable from this very moment.

This vision stands in contrast to some other Buddhist traditions that maintain a stronger emphasis on progression through stages or kalpas, or to Western philosophical models that treat time as an abstract dimension. Zen contributes a unique voice: not through metaphysical theory, but through embodied presence. It reminds us that time is not something to conquer, measure, or escape, but something to realize, in its fullness, here and now.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments