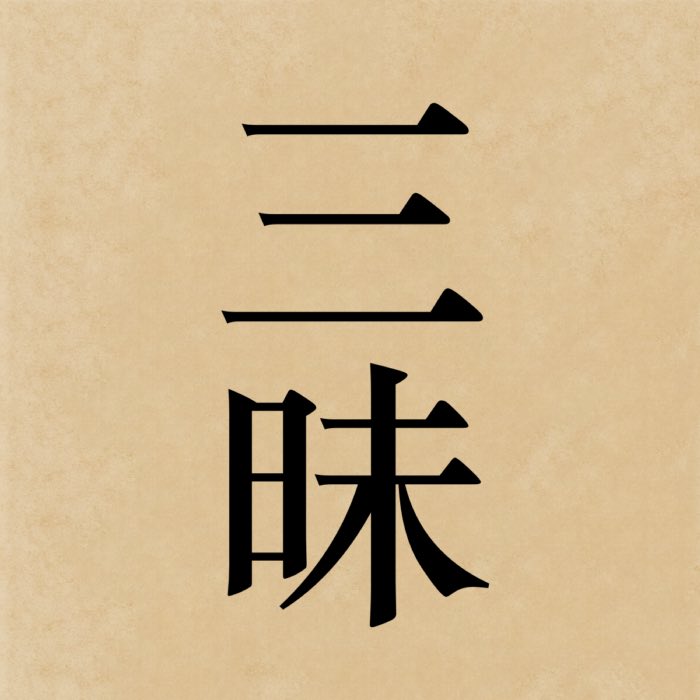

Zanmai: Meditative absorption in Zen

Samādhi (三昧, zanmai in Japanese), meaning meditative absorption or collectedness of mind, is a central concept not only in Zen but across all Buddhist traditions. In its classical form, it refers to the unification of attention, where the mind becomes fully focused and steady, undisturbed by distractions or wavering thoughts. While early Buddhist texts describe samādhi primarily in relation to the jhānas, a sequence of deep meditative states, Zen reinterprets the notion within its own emphasis on immediacy and non-duality. In this context, samādhi is not only a condition of stillness achieved in formal meditation, but also a way of inhabiting ordinary activity with full presence and non-clinging awareness.

The kanji 三昧, which reads zanmai in Japanese, literally means “samādhi”. The first character, 三 (san), means “three”. The second character, 昧 (mai), means “darkness” or “obscurity”. Together, they convey the idea of a state of deep meditative absorption that transcends ordinary consciousness.

Terminology and classical roots

The Sanskrit word samādhi comes from the prefix sam- (together, completely), the root ā (toward), and the root dhā (to place or hold), suggesting a mind completely brought together or held in one place. In the early discourses attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, samādhi is described as a fundamental aspect of the Eightfold Path (sammā samādhi, right concentration), typically associated with the four jhānas, in which the mind becomes increasingly refined, peaceful, and detached from sensory input.

Zen inherits this term but applies it less rigidly. In Japanese, samādhi is rendered as zanmai, and appears in expressions such as jijuyu-zanmai (self-fulfilling samādhi) or ichigyō-zanmai (samādhi of single-minded practice). These terms reflect a shift in emphasis: from sequential meditative stages to a more integrated quality of awareness that permeates both stillness and action.

Samādhi in Zen practice

In Zen, samādhi is cultivated most directly through zazen. However, unlike practices that aim to produce specific altered states, Zen zazen, especially in the Sōtō tradition, often avoids technique-driven concentration. Instead, it emphasizes shikantaza, or “just sitting”, in which the practitioner allows awareness to rest in itself without trying to exclude thoughts or achieve calm. Paradoxically, this very non-striving can result in profound absorption, where the mind is no longer split between observer and observed.

In Rinzai Zen, samādhi may also emerge through kōan practice, where the intense engagement with a seemingly paradoxical question collapses discursive thinking and channels the mind into unified attention. Here, samādhi does not arise from withdrawal but from total engagement — what D. T. Suzuki described as an “active passivity”, in which action flows naturally without self-conscious interference.

Zen masters often refer to different forms of samādhi, not as stages to be attained but as descriptive markers of meditative presence:

- Jijuyu-zanmai (自受用三昧) – “self-fulfilling samādhi”: the meditative absorption that arises simply from sitting, without seeking anything.

- Ichigyō-zanmai (一行三昧) – “one-practice samādhi”: full absorption in a single activity, such as chanting, sweeping, or eating.

- Hōgyō-zanmai (法行三昧) – “dharma-practice samādhi”: the continuity of practice across changing conditions.

These expressions indicate that samādhi in Zen is not separate from daily life. It is not limited to silence or withdrawal but includes dynamic engagement when it arises from a mind that is settled and unentangled.

Comparison with other Buddhist traditions

In Theravāda Buddhism, samādhi is typically cultivated through systematic concentration on objects such as the breath (ānāpānasati) or loving-kindness (mettā), leading to absorption states with increasingly subtle factors. The emphasis is on precision and refinement, with samādhi as a necessary precondition for insight (vipassanā).

In Zen, the boundary between samādhi and insight is less clearly drawn. Zen regards deep absorption and awakening as intertwined, with samādhi seen as both a natural outcome of non-grasping awareness and a condition that supports direct realization. Rather than moving through prescribed stages, Zen practitioners aim to embody samādhi as a fluid and spontaneous quality — present even while walking, working, or encountering others.

This attitude reflects Zen’s broader Mahāyāna orientation, where emptiness (śūnyatā) and non-duality override categorical distinctions. Samādhi is not an exceptional state to be preserved but a baseline of undistorted presence.

Philosophical significance

Philosophically, samādhi in Zen challenges the dualism between contemplation and action. It suggests that meditative depth does not require withdrawal from the world but can manifest in direct, uncontrived participation. This is consonant with the broader Zen critique of striving and objectification: the moment one tries to “enter” samādhi as a goal, it becomes a conceptual object and eludes experience.

Samādhi, then, is not about control but receptivity. It is the stillness that does not resist movement, the clarity that does not impose form. In its fullest sense, it names the harmony of body, breath, and mind — unified not by force, but by letting go.

Conclusion

Samādhi in Zen reflects a distinctive approach to meditative presence: it is not confined to silent sitting or progressive attainment, but includes a fluid attentiveness that pervades daily activity. Rather than separating formal meditation from the rest of life, Zen understands samādhi as a unified, embodied responsiveness — one that emerges when clinging falls away and the mind becomes unobstructed. This framing departs from traditions that associate meditative depth with withdrawal or altered states; instead, it presents samādhi as a form of clarity available in ordinary conditions. Philosophically, it challenges models that tie realization to technique or control, suggesting instead that freedom is most fully expressed through natural, unforced presence. In this way, Zen samādhi remains consistent with the early Buddhist emphasis on non-clinging, while offering a non-linear, integrative vision of awareness as inherently accessible and already embedded in everyday life.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Dogen Zenji, Shobogenzo – Die Schatzkammer des wahren Dharma-Auges, 4 Bände, 2013, Verlage: Kristkeitz Werner, Übersetzung: Ritsunen Gabriele Linnebach, Gudo Wafu Nishijima, ISBN: 9783921508909

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments