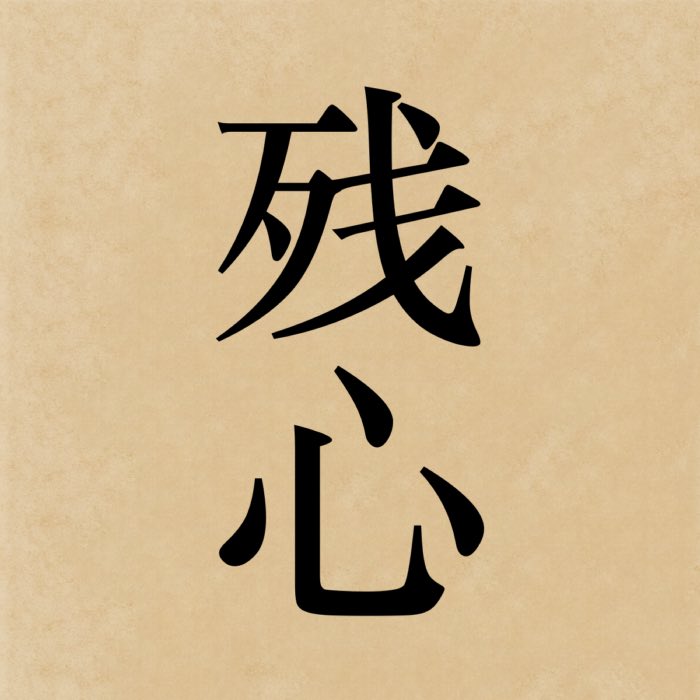

Zanshin: Lingering awareness in Zen

Zanshin (残心), often translated as “lingering mind” or “remaining mind”, refers to a state of sustained attention and awareness that persists before, during, and after an action. Originally developed and emphasized in Japanese martial arts, zanshin has deep roots in Zen and embodies one of its most practical expressions: presence without fixation. While other states in Zen emphasize emptiness, spontaneity, or letting go, zanshin emphasizes continuity — a thread of unbroken attention that is both situationally aware and internally calm.

The kanji 残心, which reads zanshin in Japanese, literally means “remaining mind”. The first character, 残 (zan), means “remaining” or “leftover”. The second character, 心 (shin), means “mind” or “heart-mind”. Together, they convey the idea of a state of awareness that remains present and attentive even after an action has been completed.

Etymology and usage

The Japanese term zanshin combines 残 (zan, “remaining”) and 心 (shin, “mind” or “heart-mind”). It describes the quality of mind that does not collapse into distraction or conclusion, even after an action is completed. In martial disciplines such as archery, swordsmanship, or Aikido, zanshin refers to the attitude maintained after releasing an arrow or completing a strike: a poised, alert readiness that neither dwells on the past nor anticipates the future.

Within Zen, zanshin becomes a metaphor for mindful continuity. It does not imply rigid control, but rather a relaxed attentiveness that allows awareness to flow through all phases of an action. This principle is equally present in traditional Zen arts — tea ceremony, brush painting, or flower arranging — where the act is never viewed in isolation but as part of an unbroken arc of attention.

Zanshin in Zen practice

In formal zazen, zanshin manifests as the capacity to remain alert and present throughout the sitting period. The practitioner does not slip into dullness, nor does the mind rush ahead. There is a steady receptivity to sensations, thoughts, and environmental cues — without becoming absorbed or reactive. When the bell rings to end the session, zanshin continues into the next action, whether bowing, standing, or walking.

In everyday Zen practice, zanshin refers to the quality of being fully engaged in each activity while retaining peripheral awareness. For example, when washing a bowl, the practitioner focuses entirely on the act — but not in a narrow or tunnel-visioned way. There is a sensitivity to one’s surroundings, posture, breath, and the unfolding moment. This form of mindfulness does not suppress thought or experience, but permits no negligence.

Zen teachings often emphasize that genuine presence includes what happens after the action. A bow is not complete until one has returned to a composed standing posture. A conversation is not finished until one has let go of the impulse to evaluate it. Zanshin extends mindfulness beyond the immediate gesture into the larger field of life.

Buddhist background and philosophical relevance

In early Buddhist terms, zanshin corresponds to the continuity of sati (mindfulness) as practiced in the four foundations of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna). The instruction to remain aware of body, feeling, mind, and mental objects applies not only during meditation but in all activities. Where early Buddhism emphasizes this in analytic terms, Zen condenses it into experiential forms like zanshin — a single word encapsulating a non-fragmented awareness.

Philosophically, zanshin resists compartmentalization. It does not separate meditation from life, action from awareness, or the past from the now. Its emphasis on continuity challenges the habitual tendency to treat experience as a series of discrete events, encouraging instead an integrated and processual view of reality. This reflects core Buddhist teachings on impermanence (anicca) and dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda).

Unlike some Western notions of attention that prioritize intensity or productivity, zanshin emphasizes quality and balance. It is not focused on achieving a goal but on dwelling fully within a process. This makes it particularly relevant in contemporary contexts, where constant distraction and compartmentalization fragment experience. Zanshin offers a model of awareness that is simultaneously relaxed, responsive, and undivided.

Conclusion

Zanshin exemplifies the Zen understanding that mindfulness is not confined to formal practice or heightened states of awareness, but consists of sustained, undistracted engagement with life as it unfolds. It emphasizes the value of continuity over intensity and integration over compartmentalization. In doing so, zanshin broadens the scope of mindfulness beyond episodic meditation and aligns with the early Buddhist insight that liberation arises from a clear, ongoing awareness of body, feeling, mind, and phenomena. As a concept, zanshin also offers a critical lens on modern habits of distraction and task-orientation. It challenges the tendency to isolate attention to short bursts of performance and instead encourages a stable attentiveness that persists through action and reflection alike. In this way, it remains a practically relevant and philosophically grounded element of Zen training.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments