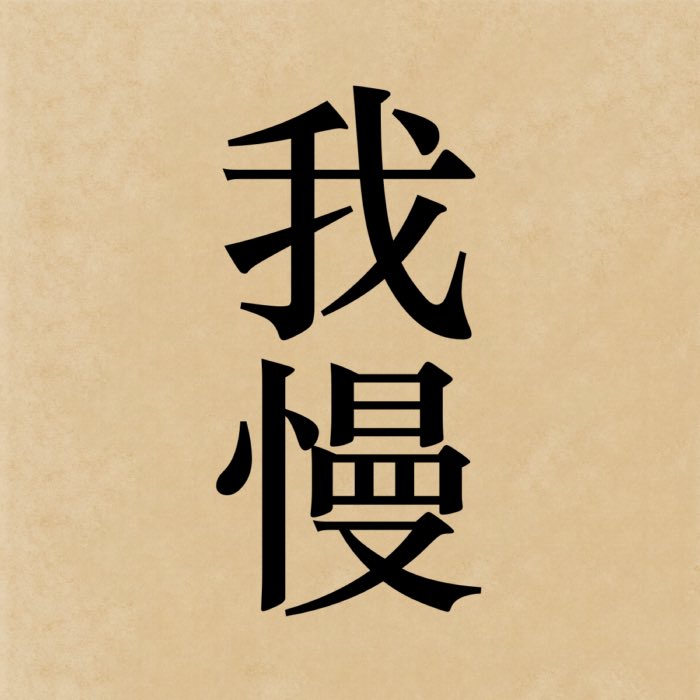

Gaman: Enduring patience in Zen

Gaman (我慢), often translated as “enduring patience” or “perseverance with dignity”, is a mental attitude highly valued not only in Japanese culture broadly but also within Zen practice. In the Zen context, gaman signifies the capacity to endure discomfort, difficulty, or adversity without complaint, agitation, or withdrawal. Unlike passive resignation, gaman is an active endurance grounded in clarity and acceptance of reality as it is. It reflects a profound cultivation of equanimity (upekkhā) and patience (khanti), central virtues within the Buddhist path.

The kanji 我慢, which reads gaman in Japanese, literally means “enduring patience”. The first character, 我 (ga), means “self” or “ego”. The second character, 慢 (man), means “pride” or “arrogance”. Together, they convey the idea of enduring hardship with dignity and without complaint. In Zen, gaman is not merely a passive acceptance of suffering but an active engagement with it, allowing practitioners to cultivate resilience and equanimity in the face of life’s challenges.

Etymology and traditional usage

The term gaman is composed of two characters: 我 (ga, “self” or “ego”) and 慢 (man, “pride” or “arrogance”). Originally, in Buddhist contexts, gaman referred to conceit — the subtle clinging to a sense of self. However, in the cultural development of Japan, the term evolved into a positive value, emphasizing self-restraint, perseverance, and dignified endurance, especially in difficult circumstances.

In Zen, gaman is seen as the strength to bear suffering without being overwhelmed by it, without needing to dramatize or reject it. It is the cultivation of a mind that can remain steady through physical pain during meditation, emotional turbulence, or the frustrations of daily life. Importantly, it does not mean repression but the clear acknowledgment and endurance of conditions without reactive grasping or aversion.

Gaman in Zen practice

During zazen, gaman manifests when practitioners experience physical discomfort, restlessness, or boredom. Rather than immediately adjusting posture, shifting, or giving up, practitioners are encouraged to observe these sensations and mind states without succumbing to them. This patience is not masochistic endurance but the training of a mind that can coexist with discomfort without being controlled by it.

In the monastic context, gaman supports communal life, where interpersonal frictions, strict schedules, and repetitive tasks test one’s emotional resilience. By enduring without complaint, practitioners develop humility and reduce the centrality of the ego, aligning themselves with the communal and ethical dimensions of practice.

Outside formal settings, gaman extends into everyday life: facing illness, aging, failure, or disappointment with quiet dignity rather than bitterness or despair. It is an embodied understanding that impermanence (anicca) entails difficulty, and that peace arises not from manipulating circumstances but from meeting them with an unshakable heart.

Buddhist background and philosophical resonance

The cultivation of patience (khanti) is a well-established aspect of the Buddhist path, explicitly listed among the pāramitās (perfections) that Bodhisattvas develop. Siddhartha Gautama described patience as the “supreme austerity” (khanti paramam tapo titikkhā), suggesting that endurance in the face of suffering is not secondary but central to spiritual development.

Gaman in Zen embodies this understanding in a concrete, lived way. It moves beyond theoretical acceptance of suffering to the bodily, emotional, and relational practices of bearing difficulty without adding secondary suffering — resentment, self-pity, or rage. By cultivating gaman, practitioners learn to inhabit their circumstances fully, without flinching.

Compared to Western models that often valorize overcoming or mastering adversity through assertion and change, gaman emphasizes endurance without conquest. It reflects the Buddhist insight that control is illusory and that true freedom lies in the capacity to be undisturbed by what cannot be controlled.

Conclusion

Gaman illustrates a critical dimension of Zen and Buddhist practice: that spiritual maturity is reflected not by the absence of hardship but by the ability to meet difficulty without reactive resistance. It reframes endurance not as passive submission, but as an active, clear engagement with impermanence. By cultivating gaman, practitioners develop resilience that is grounded not in force or suppression, but in understanding the nature of changing conditions. In this way, gaman challenges cultural models that equate success with dominance or overcoming adversity, emphasizing instead that true freedom lies in the capacity to remain steady, compassionate, and unshaken amidst inevitable difficulties.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments