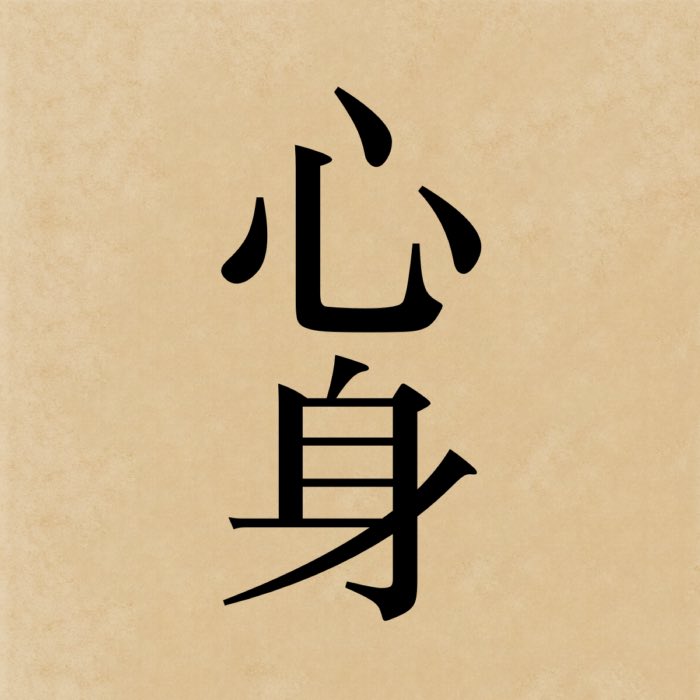

Shinshin: The unity of mind and body

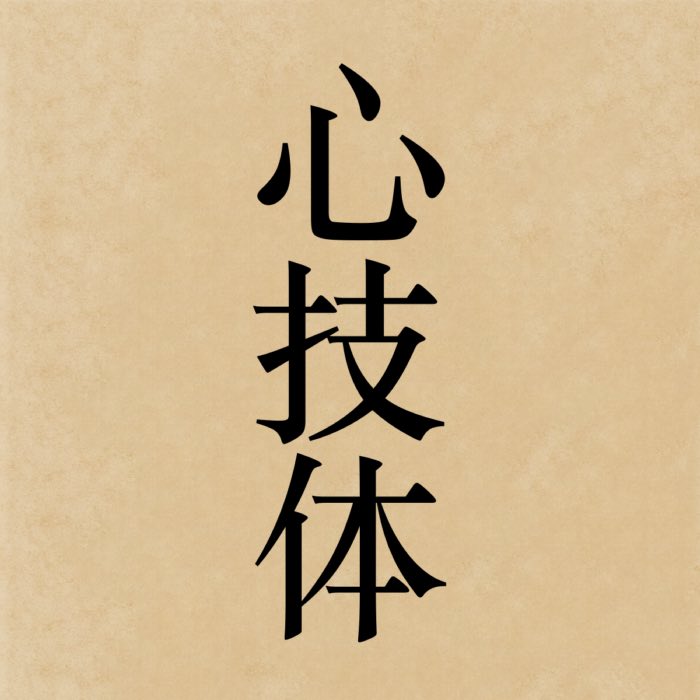

Shinshin (心身), translated as “mind and body”, refers to the inseparability of mental and physical processes in Zen practice. While the dualistic division of mind and body has shaped much of Western philosophical tradition, Zen, following the broader Buddhist understanding, emphasizes that mind and body are not two independent substances but intimately interwoven aspects of experience. Shinshin points toward the realization that awakening is not confined to mental states alone but is embodied, enacted, and experienced through the totality of one’s being. This foundation also prepares the ground for the more specific integration of mind, skill, and body discussed in the concept of shingitai, where Zen practice further refines the unity of presence into dynamic engagement with action and technique.

The kanji 心身, which reads shinshin in Japanese, literally means “mind and body”. The first character, 心 (shin), means “mind” or “heart-mind”. The second character, 身 (shin), means “body” or “physical form”. Together, they convey the idea of a unified state of being that integrates mental clarity and physical embodiment. In Zen, shinshin is not merely a theoretical concept but a lived experience that permeates all aspects of practice and daily life.

Etymology and usage

The term shinshin consists of two identical components:

- 心 (shin): mind, heart-mind, or consciousness

- 身 (shin): body, physical form

The repetition highlights the close relationship between the two. Rather than viewing body and mind as separate entities that interact, Zen treats them as expressions of a single, dynamic process. Thought influences posture, breathing influences emotion, and attentiveness transforms physical comportment.

This understanding appears not only in meditation but also in all aspects of Zen training, from ritual movement to manual labor. Every act becomes a site where mind and body meet, revealing their non-separation.

Shinshin in Zen practice

In zazen, shinshin is most directly cultivated. Proper posture, upright yet relaxed, supports a balanced and attentive mind. The steadiness of the breath influences emotional stability. Conversely, mental agitation is often reflected in physical restlessness. In Zen instructions, correcting the body is often a preliminary way to help settle the mind.

The emphasis on shinshin is also evident in kinhin (walking meditation), where slow, deliberate steps synchronize with breathing and attentive presence. In Zen arts such as calligraphy, tea ceremony, or martial arts, the integration of body and mind is paramount. A beautiful brushstroke is not merely a technical achievement but the embodied expression of clarity.

Zen teachers frequently highlight that realization must penetrate the body, not remain at the level of abstract thought. Awakening is thus not an idea about life, but a transformation of how one moves, breathes, speaks, and relates.

Buddhist foundations and philosophical background

The unity of mind and body in Zen reflects core Buddhist principles. Early Buddhist teachings stress the role of bodily awareness in meditation, beginning with mindfulness of the body (kāyānupassanā). The cultivation of mindfulness starts with how one sits, walks, breathes, and stands.

Furthermore, dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda) shows that physical, mental, and emotional phenomena arise interdependently. The notion of a separate, autonomous mind distinct from the body is a conceptual illusion. Realizing the dynamic unity of mind and body undermines the reified self and opens the way to a deeper understanding of non-self (anattā).

Philosophically, shinshin challenges Cartesian dualism, which has shaped much of Western thought. Zen does not propose that body and mind are identical substances, but that they are inseparable dimensions of lived experience. This perspective shifts the emphasis from speculation about “what” we are to attention to “how” we live.

Conclusion

Shinshin articulates a core insight of Zen: that true realization cannot be confined to intellectual understanding but must involve the full integration of body and mind. By emphasizing their inseparability, Zen redefines awakening as an embodied condition, where thought, action, sensation, and awareness arise from a unified field rather than from divided faculties. Critically, shinshin challenges deeply entrenched dualisms in Western and some Buddhist traditions that tend to privilege mind over body. It asserts that the mode of being — how one moves, breathes, and interacts — is itself an expression of insight or delusion. In this embodied realization, the conventional division between self and world softens, making it possible to perceive existence not as a series of isolated experiences but as an interconnected, dynamic process. This understanding situates awakening not in abstraction but in the direct, integrated experience of everyday life.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments