Shunryu Suzuki: Establishing Zen Practice in America

Shunryu Suzuki (1904-1971), a humble yet transformative figure in the history of Zen Buddhism, played a pivotal role in bringing authentic Zen practice to the United States. Arriving in San Francisco in 1959, Suzuki encountered a generation of seekers eager for spiritual depth and simplicity. Through his gentle guidance, he emphasized the essence of Zen: sitting meditation (zazen), mindfulness, and the cultivation of “beginner’s mind” (shoshin). In this post, we explore Suzuki’s life, teachings, and enduring influence, highlighting how his quiet yet profound approach helped establish Zen as a living tradition in the West.

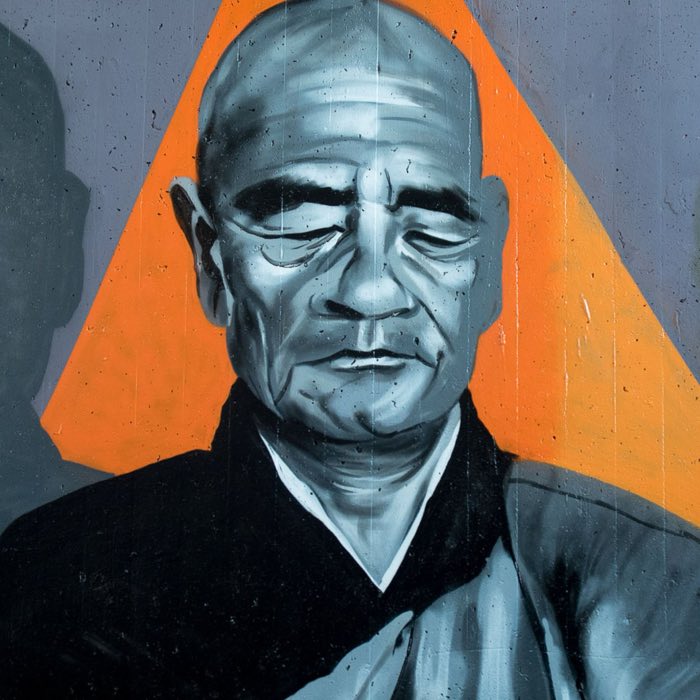

Shunryu Suzuki, sketched by Sadobeam, based on a photograph by Robert S. Boni, from the original back cover of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, 1970. Source: deviantart.comꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Biography

Shunryu Suzuki was born in 1904 in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. His father was a Sōtō Zen priest, and from a young age, Suzuki was immersed in the rituals and disciplines of temple life. At the age of twelve, he formally entered monastic training under his father’s friend Gyokujun So-on, a strict and demanding master who greatly shaped Suzuki’s commitment to zazen and the basics of Zen practice.

Suzuki received Dharma transmission from So-on in 1926 and later pursued university studies in Buddhist philosophy at Komazawa University in Tokyo. During these years, Japan was undergoing rapid modernization, and Suzuki’s formation reflected a synthesis of traditional Zen discipline with an awareness of the emerging modern world.

After years of serving as a temple priest in Japan, Suzuki accepted an invitation to serve the small, aging Japanese-American Buddhist community in San Francisco in 1959. What he found there — a form of Buddhism that had largely become ceremonial and disconnected from daily meditation practice — inspired him to adapt his mission. He quickly attracted a new, predominantly non-Japanese audience hungry for authentic spiritual practice.

Suzuki continued his work until his death in 1971. Despite his relatively short time in America, his influence was profound, and the institutions he helped establish continue to thrive today.

Spreading Zen to the West

Upon arriving in San Francisco, Shunryu Suzuki encountered a generation of Americans, students, beatniks, and seekers, disillusioned with materialism and traditional religious institutions. Rather than offering complex doctrinal lectures, Suzuki taught in simple language, emphasizing the essentials of Zen practice: posture, breath, attitude, and everyday mindfulness.

He quietly and persistently guided his students toward establishing a daily zazen practice, explaining that true Zen was not about gaining special experiences but about completely being in each moment. His teachings were marked by a profound patience and a humility that deeply resonated with American audiences.

In 1962, Suzuki and his students founded the San Francisco Zen Center, which quickly became one of the most important hubs for Zen practice in the United States. Recognizing the need for a residential training environment, Suzuki later oversaw the purchase of Tassajara Hot Springs in 1967, which he transformed into the first Zen Buddhist monastery outside of Asia: Tassajara Zen Mountain Center.

Through these initiatives, Suzuki not only introduced Zen practice to America, but he rooted it firmly in American soil, adapting traditional training structures to new cultural contexts without diluting their spirit.

Refreshing Zen in America

Suzuki’s approach to Zen was characterized by its clarity, accessibility, and emphasis on the ordinariness of practice. Rather than presenting Zen as an exotic or esoteric tradition, he framed it as a deeply human path: one of attention, effort, and acceptance.

His famous expression, “Beginner’s mind” (shoshin) captured the heart of his teaching: that true spiritual practice requires the attitude of openness, curiosity, and humility, even (and especially) after years of practice. As he put it: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.”

Unlike Deshimaru’s stern emphasis on discipline or Daisetz Suzuki’s philosophical interpretation, Shunryu Suzuki created an environment where sincere effort, patience, and compassion were the measures of genuine practice. He encouraged practitioners to approach zazen not as a means to an end but as the full expression of Buddha-nature itself.

His teachings, later compiled by his students into the influential book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (1970), became one of the most widely read and respected introductions to Zen in the West.

Critiques and legacy

While Suzuki’s quiet style endeared him to many students, some critics have noted that his teachings could at times lack systematic rigor or a full exposition of the Zen tradition’s historical and doctrinal breadth. His emphasis on “just sitting” and beginner’s mind was profound but could risk, in some cases, a simplified view of Zen’s complexity.

This approach contrasts notably with Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, who introduced Zen to the West primarily through scholarly writings and philosophical interpretation. Daisetz Suzuki sought to explain Zen’s existential and intuitive dimensions using the language of Western philosophy and psychology, reaching academics and intellectuals. In contrast, Shunryu Suzuki focused less on theoretical exposition and more on fostering a living, breathing practice community. His emphasis on direct experience over philosophical analysis made Zen accessible to a broader audience seeking practical spiritual engagement.

Moreover, Shunryu Suzuki’s premature death in 1971 cut short the development of a more mature institutional framework for American Zen. In the years following his death, the San Francisco Zen Center would grapple with leadership challenges that perhaps reflected the absence of Suzuki’s steady, patient guidance.

Nonetheless, Shunryu Suzuki’s contribution to the establishment of Zen in America remains foundational. Through his humility, warmth, and deep sincerity, he inspired a generation to see Zen not as a distant cultural artifact, but as an intimate, immediate practice rooted in everyday life.

Today, the San Francisco Zen Center and its affiliated centers, Green Gulch Farm, Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, and others, continue Suzuki’s lineage, offering rigorous practice opportunities to thousands of practitioners across the world.

Conclusion

Shunryu Suzuki occupies a unique place in the history of Zen’s spread to the West. In contrast to Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki’s intellectual bridge-building and Taisen Deshimaru’s stern physical rigor, Shunryu Suzuki offered a path marked by gentleness, patience, and human warmth. His emphasis on “beginner’s mind” remains one of the most enduring contributions to modern spiritual culture.

Rather than presenting Zen as an exotic system to be mastered or a body of knowledge to be acquired, Suzuki revealed it as an ongoing process of return: to the breath, to the posture, to the immediacy of life itself. He showed that awakening was not a dramatic event but the deepening appreciation of the ordinary.

By quietly nurturing communities, establishing institutions, and most importantly, embodying the spirit of Zen in his own simple presence, Shunryu Suzuki made it possible for Zen to take root in the United States, not as a fleeting trend but as a living, evolving tradition.

His legacy reminds us that in spiritual practice, as in life, it is often the quiet, persistent cultivation of the fundamentals that endures beyond all else.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

Suzuki’s most important works:

- Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind Beginner’s Mind, Weatherhill, 1970, ISBN 0-834-80079-9

- Shunryu Suzuki, Branching Streams Flow in the Darkness: Zen Talks on the Sandokai, 1st ed., University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0-520-21982-1

- Shunryu Suzuki, Not Always So: Practicing the True Spirit of Zen. Ed. Edward Espe Brown. HarperCollins, 2002, ISBN 0-060-95754-9

- Shunryu Suzuki, Zen is Right Here. Shambhala, 2007, ISBN 978-1-59030-491-4

- Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. Shambhala, 2011, ISBN 978-1-59030-849-3

- Shunryu Suzuki, To Shine One Corner of the World: moments with Shunryu Suzuki / the students of Shunryu Suzuki. Ed. David Chadwick, Broadway Books, 2001. ISBN 0-7679-0651-9

- Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Is Right Now: More Teaching Stories and Anecdotes of Shunryu Suzuki. Ed. David Chadwick. Shambhala, 2021, ISBN 978-1-611809-14-5

comments