Hellenistic encounters with India: Historical and cultural background

Long before modern globalization, the ancient world saw remarkable episodes of intercultural exchange that shaped civilizations across continents. One of the most significant of these moments occurred during the Hellenistic period, when the conquests of Alexander the Great and the rise of successor states brought the Mediterranean world into sustained contact with the Indian subcontinent. This convergence initiated a centuries-long process of political, artistic, and philosophical interaction, especially in the regions that today encompass Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India.

Greek Gods and the “Wheel of the Law” or Dharmachakra: Left: Zeus holding Nike, who hands a victory wreath over a Dharmachakra (coin of Menander II). Right: Divinity wearing chlamys and petasus pushing a Dharmachakra, with legend “He who sets in motion the Wheel of the Law” (Tillya Tepe Buddhist coin). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

This post aims to offer a structured overview of these Hellenistic-Indian encounters, clarifying the often-confused chronology of events involving Alexander’s campaigns, the Seleucid Empire, the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms, and the development of the Gandhāran cultural sphere. By situating these interactions in their historical context, we aim to better understand their role in the emergence of Greco-Buddhist art, the cross-pollination of philosophical ideas, and the long-term significance of East–West dialogue in antiquity.

The arrival of Alexander the Great

In 327 BCE, Alexander the Great launched his ambitious campaign into the Indian subcontinent, crossing the Hindu Kush into what is now northern Pakistan. His forces encountered fierce resistance, most famously in the battle against King Porus at the Hydaspes River (modern Jhelum). Despite Porus’ defeat, Alexander treated him with respect, restoring him as a local ruler — a gesture that reflected both political pragmatism and recognition of Indian sovereignty.

Alexander’s empire at the time of its maximum expansion. Within a period of a few years, Alexander, later called the Great, had conquered the Persian Empire and reached the borders of India. On his way, he founded many cities, most of them named after him. These colonization efforts and his Greek entourage lay the groundwork for the later Hellenistic influence – and exchange – in the region. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Alexander’s campaign was not solely military; it was also deeply cultural. Everywhere he went, he founded cities in the Hellenistic mold, most notably Alexandria on the Indus, which served as administrative centers, hubs of trade, and instruments of cultural dissemination. These cities brought Greek architecture, urban planning, artistic styles, coinage, and philosophical ideals into direct contact with local traditions. The Hellenistic worldview that Alexander introduced emphasized cosmopolitanism, rational inquiry, and a shared cultural identity across linguistic and ethnic lines.

However, this was not a one-way imposition. Cultural contact necessarily implies mutual exchange. Greek soldiers, administrators, and settlers were exposed to Indian customs, religious practices, and philosophical teachings. Greek sources report a mixture of astonishment and admiration for Indian gymnosophists (naked philosophers), vegetarianism, and forms of political organization. This curiosity paved the way for long-term philosophical engagement, as well as the integration of Indian ideas into Hellenistic discourse.

The naval expedition of Nearchus, one of Alexander’s admirals, also helped establish a maritime connection between the Indus Valley and the Persian Gulf, contributing to the emergence of sustained trade and communication routes, which further facilitated cultural exchange.

Locally, in the regions Alexander left behind, a blending of cultures occurred that laid the groundwork for what would later flourish as Greco-Buddhism. The seeds of syncretism were planted early: in mixed settlements, shared markets, bilingual inscriptions, and in the aesthetic and spiritual cross-fertilization that would define the centuries to come.

The formation of Hellenistic successor states

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, his vast empire fragmented among his generals, known as the Diadochi. One of the most powerful successor states to emerge was the Seleucid Empire, founded by Seleucus I Nicator. This empire inherited the easternmost territories of Alexander’s realm, including parts of Central Asia and regions abutting the northwestern Indian subcontinent.

The Diadochi fought over and carved up Alexander’s empire into several kingdoms after his death, a legacy which reigned on and continued the influence of ancient Greek culture abroad for over 300 more years. This map depicts the kingdoms of the Diadochi c. 301 BCE, after the Battle of Ipsus. The five kingdoms of the Diadochi were: Kingdom of Ptolemy I Soter (violet; mostly Egypt and Northern Africa), Kingdom of Cassander (green; Macedonia and Greek peninsula), Kingdom of Lysimachus (orange; Near East and Bosporus), Empire of Seleucus I Nicator (yellow; Asian part of Alexander’s empire, covering, among other, Mesopotamia, Persia – and parts of India), and Kingdom of Epirus (purple; West strip of the Greek peninsula). Other entities indicated on the map are: Carthaginian Empire (violet-purple), Roman Republic (cyan), and Greek colonies (darker green). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Around 305 BCE, Seleucus I launched a campaign to reassert control over the territories bordering the Indian frontier. However, he soon encountered Chandragupta Maurya, the ambitious founder of the Maurya Empire, who had already unified much of northern India. Rather than continue a costly military conflict, the two leaders negotiated a diplomatic settlement: Seleucus ceded considerable territory in what is now eastern Afghanistan and Pakistan in exchange for 500 war elephants — a prized asset that would soon bolster his forces in Western Asia.

Hellenistic kingdoms as they existed in 240 BCE, eight decades after the death of Alexander the Great. Note the Seleucid Empire (green) and the Maurya Empire (brown). The Seleucid Empire was one of the largest empires in history, stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Indus River. It was a melting pot of cultures, languages, and religions, with a diverse population that included Greeks, Persians, and various local peoples. The empire was known for its cosmopolitan cities, such as Antioch and Seleucia, which were centers of trade, culture, and learning. The Maurya Empire, on the other hand, was one of the largest empires in ancient India, known for its political unification and administrative efficiency. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

This treaty not only marked a pragmatic resolution between two expanding empires but also inaugurated a period of official contact and cultural exchange. As part of this rapprochement, Seleucus sent an ambassador, Megasthenes, to the Maurya court at Pāṭaliputra (modern Patna). Megasthenes remained there for several years and compiled extensive observations about Indian geography, society, economy, religion, and governance. Though his original work, the Indica, is now lost, later Greek and Roman authors preserved many excerpts.

Megasthenes’ account reveals a mixture of fascination, misunderstanding, and respect for Indian civilization. His descriptions, though shaped by Greek paradigms, also reflect a genuine curiosity and an attempt to document the uniqueness of Indian society. These early records contributed to a gradually widening Greek understanding of India and established a foundation for continued intellectual and commercial contact between the Hellenistic world and the Indian subcontinent.

Importantly, the Seleucid-Maurya treaty also set a precedent: the Hellenistic world, while expansive and confident, was open to diplomatic compromise and cultural exchange. It was not a monologue of conquest but a dialogue of powers. And in the border zones where Greek and Indian cultures met, the conditions were created for the emergence of hybrid identities, artistic fusion, and philosophical interaction that would flourish in the coming centuries.

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and Indo-Greek expansion

By the mid-3rd century BCE, the eastern territories of the Seleucid Empire began to fragment. Around 250 BCE, the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom emerged as an independent Hellenistic state in the region of Bactria, centered around modern-day northern Afghanistan. Founded by Diodotus I, the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom marked a significant shift: Hellenistic culture was no longer simply imposed by imperial force but had taken root and begun to evolve independently in the East.

Map of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom at its maximum extent, circa 180 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Over time, the Greco-Bactrian rulers expanded their influence further south and east, eventually crossing the Hindu Kush into the Indian subcontinent. There, they established what came to be known as the Indo-Greek Kingdoms, which controlled large parts of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and parts of northwestern India. These kingdoms became some of the most vibrant zones of cultural contact in the ancient world.

Gold coin of Diodotus c. 245 BC. The reverse shows Zeus standing, holding aegis and thunderbolt. The Greek inscription reads: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΔΙΟΔΟΤΟΥ, Basileōs Diodotou – “(of) King Diodotus”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Greek and Indian cultures intertwined in the Indo-Greek territories in unprecedented ways. Hellenistic rulers issued bilingual coinage in Greek and Kharosthi or Brahmi scripts, combining Greek deities and royal iconography with local symbols. Greek and Indian architectural and artistic motifs appeared side by side in temples and urban spaces. The use of Greek as an administrative language alongside local dialects helped facilitate intellectual and bureaucratic exchange, while intermarriage and mixed communities fostered new hybrid identities.

The Indo-Greek Kingdoms in 100–150 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Traditional depiction of the Maurya Empire under Ashoka as a solid mass of Maurya-controlled territory, c. 250 BCE. Both, the Maurya Empire and the Indo-Greek Kingdoms stood in a complex relationship of competition and cooperation. The Indo-Greek rulers often sought to legitimize their authority by associating themselves with the legacy of the Maurya Empire, while the Maurya rulers, particularly Ashoka, recognized the importance of diplomacy and cultural exchange with their Hellenistic neighbors. This dynamic interplay between the two empires contributed to rich cultural and political interactions that shaped the history of the region. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

One of the most celebrated figures of the Indo-Greek period is King Menander I (known in Buddhist tradition as Milinda), who ruled in the 2nd century BCE. His reign is often seen as a high point of Greco-Indian interaction. According to Buddhist sources, Menander embraced the teachings of the Buddha and engaged in a famous philosophical dialogue with the monk Nāgasena, recorded in the Pāli text Milindapañha (“The Questions of Milinda”). Whether this account is strictly historical or partially legendary, it testifies to a remarkable cultural integration: a Greek king seriously engaging with and potentially converting to Buddhism.

Bilingual coin of Eucratides I in the Indian standard, on the obverse Greek inscription reads: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΕΥΚΡΑΤΙΔΟΥ, Basileōs Megalou Eukratidou – “(of) Great King Eucratides”; on the reverse Pāli language in Kharoshthi legend reads: Maharajasa Evukratidasa, “of Great King Eucratides”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms did more than maintain Hellenistic presence in the East. They localized it, transforming it through dynamic interaction with Indian thought, governance, and artistic expression. These hybrid polities laid crucial groundwork for the later emergence of Greco-Buddhism in Gandhāra and demonstrate how political fragmentation could paradoxically foster rich cultural synthesis.

Corinthian capitals like the depicted one, found at Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BCE, highlight the influence of Hellenistic architectural styles on Gandhāran art. The Corinthian order, with its elaborate acanthus leaves and scrolls, was adapted to local contexts, demonstrating the fluidity of artistic exchange. The use of such motifs in Buddhist contexts reflects a broader trend of syncretism, where Greek aesthetics were integrated into Indian religious iconography. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Cross-cultural exchange in art and religion

One of the most striking outcomes of Hellenistic contact with the Indian subcontinent is the emergence of a syncretic artistic tradition known today as Greco-Buddhism. This fusion is most vividly represented in the Gandhāra region, which became a prominent center of Buddhist culture and artistic production from the 1st century BCE onward. Gandhāran art reflects the deep entanglement of Hellenistic and Indian traditions, producing a visual vocabulary that would profoundly influence the representation of Buddhist themes throughout Asia.

Left: Bronze Heracles statuette, found at Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Sculpture of an old man, possibly a philosopher, found at Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

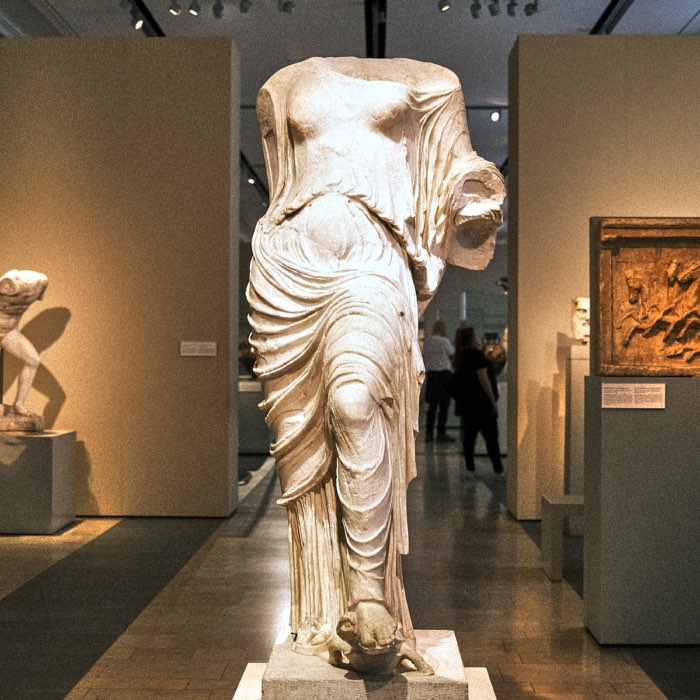

Greco-Buddhist sculpture is characterized by its classical naturalism, which sharply contrasts with earlier, more symbolic representations of the Buddha. For the first time, the Buddha was depicted in anthropomorphic form — clothed in a flowing toga-like robe, with finely curled hair, realistic musculature, and serene Hellenistic facial expressions. These images drew heavily on Greek sculptural norms, echoing the aesthetics of gods and philosophers in the Mediterranean world.

Hellenistic culture in the Indian subcontinent: Greek clothes, amphoras, wine and music. Detail from Chakhil-i-Ghoundi Stupa, Hadda, Gandhara, 1st century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The adoption of human form for the Buddha was not simply an artistic choice; it represented a theological and philosophical shift, enabled by cross-cultural contact. The influence of Greek visual realism and anthropocentrism likely encouraged Buddhist artists and patrons to explore new ways of expressing enlightenment and compassion through bodily form. At the same time, these innovations remained grounded in Indian religious thought, creating a hybrid idiom that resonated across cultures.

Siddhartha Gautama as the Buddha, in a Greco-Buddhist style, 1st–2nd century CE, Gandhara (Peshawar basin, modern day Pakistan). The figure is depicted with a halo and standing in a relaxed pose, wearing a robe similar to that of Hellenistic deities. The sculpture reflects the blending of Greek and Indian artistic traditions, showcasing the influence of Hellenistic aesthetics on Buddhist iconography. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Gandhāra region, located primarily in present-day northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, had long served as a cultural crossroads due to its strategic position along trade routes connecting Central Asia, Persia, and the Indian subcontinent. With the arrival of Hellenistic influences through the Indo-Greek and Greco-Bactrian kingdoms, Gandhāra became the epicenter of a remarkable artistic and religious fusion that we now refer to as Greco-Buddhism.

Buddha Daibutsu statue, Kamakura, Japan, cast in bronze in the year 1252 CE (Kenchō 4), during the Kamakura period. The deep and lasting impact of Hellenistic influences on Buddhist art is evident in the artistic traditions that emerged in Gandhāra and later spread throughout Asia. The blending of Greek and Indian aesthetics in the representation of the Buddha and other figures laid the groundwork for a rich visual language that would resonate across cultures, influencing Buddhist art in regions as far away as Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. For instance, the Buddha is commonly depicted wearing a robe similar to that of Hellenistic deities, with a serene expression and (often) a halo, as seen in the Kamakura Daibutsu. This fusion of styles reflects the enduring legacy of Greco-Buddhist art and its profound impact on the development of Buddhist iconography across Asia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Syncretism in Gandhāran art extended beyond formal elements. Greek mythological figures and motifs were adapted into Buddhist contexts. Dionysian imagery, for instance, sometimes found its way into decorative elements. The Greek hero Heracles, known for his strength and protective nature, was reimagined as Vajrapāṇi, the guardian of the Buddha, wielding the thunderbolt weapon (vajra). Such visual translations reveal the degree to which cultural boundaries were fluid and adaptable.

This artistic syncretism was made possible by sustained exchange: itinerant artists, patronage by Indo-Greek and local rulers, and the cosmopolitan environment of trade cities all contributed to a shared visual culture. Gandhāra thus stands as a testament to the power of artistic exchange — not as the result of conquest or domination, but as the product of genuine intercultural dialogue and creative synthesis.

Philosophical encounters and mutual perceptions

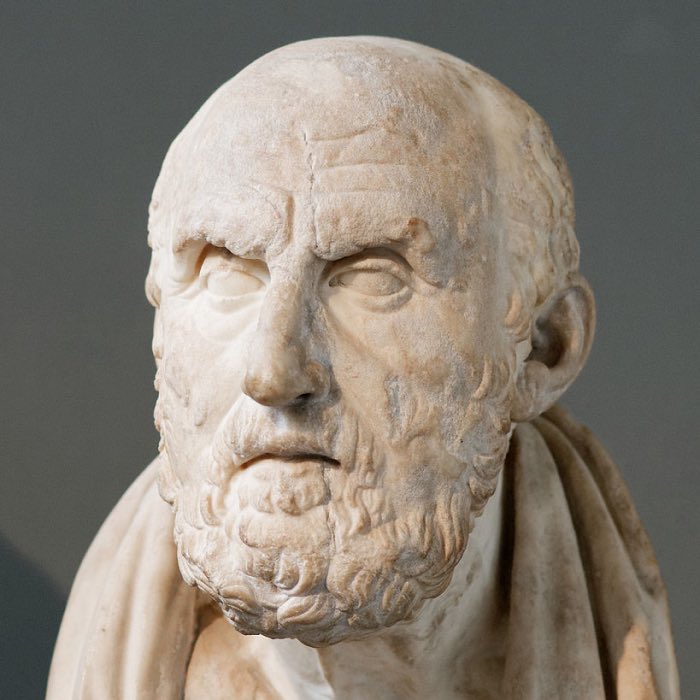

Beyond the realms of warfare, governance, and art, one of the most profound forms of exchange between the Hellenistic world and India occurred in the domain of philosophy. These encounters reveal a mutual fascination with fundamental questions of life, ethics, and the nature of reality. Greek and Indian thinkers did not merely observe one another from a distance. They engaged in genuine inquiry, sometimes even direct dialogue, leaving behind a legacy of intellectual exchange that would echo through centuries.

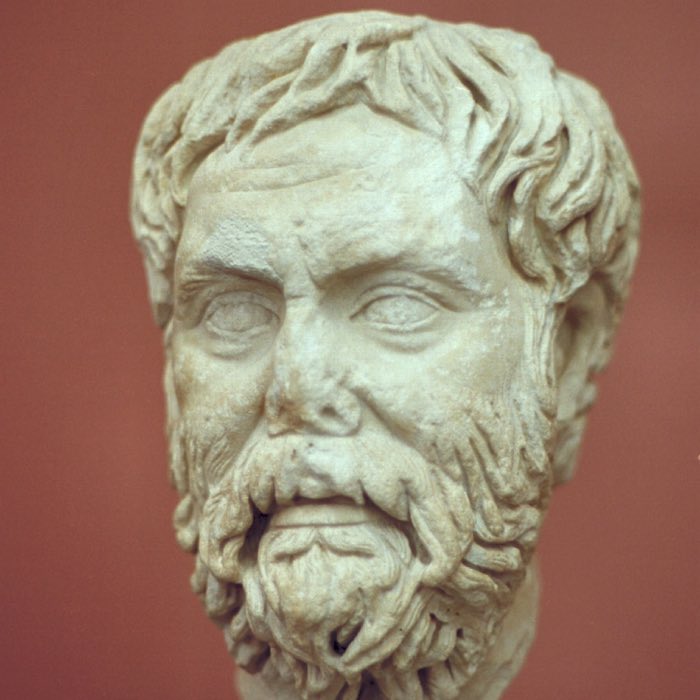

One of the most intriguing anecdotes is the purported meeting between Pyrrho of Elis, the Greek philosopher considered the founder of Skepticism, and Indian gymnosophists — ascetic philosophers encountered during Alexander’s campaigns. Though details remain speculative, ancient sources suggest that Pyrrho’s exposure to Indian modes of thought, particularly their emphasis on detachment, equanimity, and the unknowability of ultimate truths, played a formative role in shaping his philosophical outlook. This early example illustrates the permeability of conceptual boundaries between East and West.

Pyrrho of Elis, marble head, early Roman copy, 2nd century BCE. Bronze Greek original was from the 4th century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Interestingly, centuries later, echoes of this contact may have resurfaced in reverse. Some scholars have suggested that Nāgārjuna, the foundational philosopher of the Madhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism, may have been influenced, directly or indirectly, by Pyrrhonian or later Greco-Roman skepticism. Nāgārjuna’s method of radical doubt, refusal to posit intrinsic essences, and insistence on the limitations of conceptual thought resonate strikingly with Skeptical approaches, particularly those found in the writings of Sextus Empiricus, a philosopher who lived roughly during the same period as Nāgārjuna. While direct influence remains speculative, the thematic parallels underscore the possibility of a deeper, cyclical philosophical exchange across cultures and centuries.

Perhaps the most celebrated example of philosophical cross-fertilization is the Milindapañha (“The Questions of Milinda”), a Pāli text that stages a dialog between King Menander I (Milinda) and the Buddhist monk Nāgasena. Framed as a Socratic-style inquiry, the dialogue covers deep issues such as the nature of personal identity, impermanence, rebirth, and ethical conduct. Nāgasena explains the Buddhist doctrine of non-self (anattā) through analogies that echo both Indian and Hellenistic logical traditions, while King Milinda challenges and probes with intellectual rigor.

Portrait of Menander I Soter, from his coinage. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Whether or not the historical Menander actually converted to Buddhism, the Milindapañha represents a literary crystallization of what such a dialog might have entailed. It reflects an environment in which Greek rationalism and Indian metaphysics could meet on equal footing. Importantly, the text shows that both sides were open to critical thinking, systematic reasoning, and respectful debate — values shared by the philosophical traditions of both cultures.

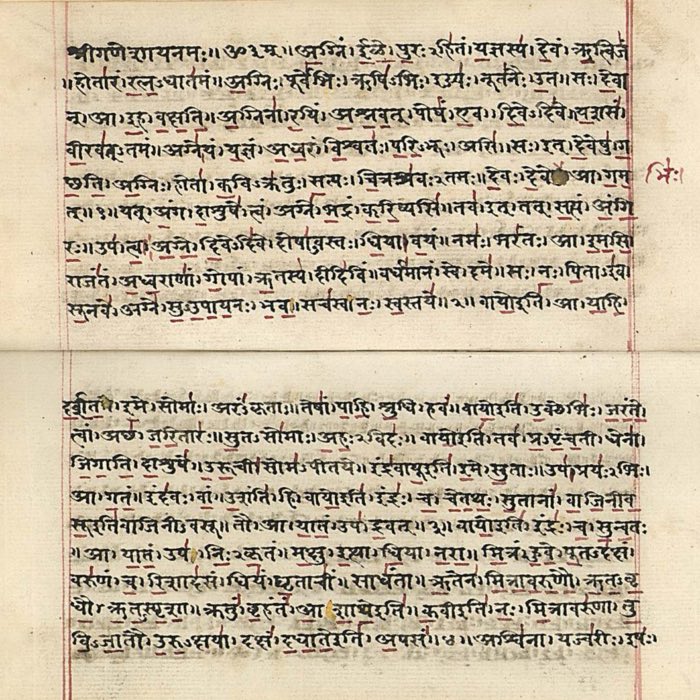

These philosophical encounters were made possible by the cosmopolitan atmosphere of cities like Ai-Khanoum and Taxila, where scholars, ascetics, and kings mingled across linguistic and cultural boundaries. The result was not the dominance of one worldview over another, but a blending and enrichment of thought, where Greek logic could illuminate [Indian spirituality](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-01-02-the_vedas/ and vice versa. This moment of genuine dialogue stands as one of the most intellectually fertile in the history of ancient intercultural exchange.

End of Hellenistic political presence and legacy

By around 10 CE, the last vestiges of the Indo-Greek Kingdoms had faded under the mounting pressure of invasions from Indo-Scythian and Central Asian groups. Despite the political collapse of Hellenistic rule in the region, the cultural and intellectual legacy of these kingdoms endured in significant ways.

Greek influence persisted most notably in Buddhist monasteries and education centers throughout Gandhāra and adjacent regions. Monastic sites continued to display Hellenistic artistic motifs for centuries, and Greek stylistic elements remained integral to the visual vocabulary of Buddhist sculpture. Inscriptions and material culture reveal that the memory of Greek presence was not erased but absorbed into the evolving cultural fabric.

Gandhāra, in particular, retained its role as a cultural melting pot during the Kushan period (1st–3rd centuries CE), which itself saw renewed patronage of Buddhism, trade, and cosmopolitan learning. The Kushans inherited and revitalized many of the artistic and intellectual traditions of the Indo-Greek period, embedding them into their own imperial identity. Greco-Buddhist artistic conventions, already well-established, flourished under Kushan sponsorship, eventually spreading to Central Asia and China via Buddhist missionaries, traders, and artisans.

Buddhist expansion in Asia. This map shows the spread of Buddhism from its origins in India to various regions across Asia, including Central Asia, China, Korea, and Japan. Mahayana Buddhism first entered the Chinese Empire (Han dynasty) through the Silk Road during the Kushan Era. The overland and maritime “Silk Roads” were interlinked and complementary, with trade routes facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices. This interconnectedness allowed for the dissemination of Buddhist teachings and art across vast distances, ultimately leading to the establishment of Buddhism as a major religious and cultural force in Asia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

This transmission extended not only to art but also to philosophical ideas. Concepts and iconographies that had been shaped in the crucible of Hellenistic-Indian exchange traveled along the Silk Roads, influencing Buddhist traditions far beyond their point of origin. Thus, even after the political structures of Hellenistic rule had vanished, their cultural footprint lived on — mutated, localized, and transmitted through new hands. In this way, the Hellenistic encounter with India continued to shape Eurasian religious and intellectual landscapes for centuries to come.

Conclusion

The Hellenistic encounter with the Indian subcontinent represents a rare and fertile moment in ancient history when two advanced civilizational spheres came into direct and sustained contact. Far from being a simple story of conquest or cultural dominance, the interactions that unfolded between the Mediterranean and Indian worlds were dynamic, reciprocal, and deeply transformative for both sides.

The Greek presence in India, first through Alexander’s campaign and later through the Seleucid, Greco-Bactrian, and Indo-Greek polities, introduced a wide array of Hellenistic ideas, artistic forms, and philosophical concepts into South Asia. Yet Buddhism, far from being “westernized,” absorbed and integrated these elements skillfully, creating new hybrid forms such as Greco-Buddhist art and texts like the Milindapañha. These forms reflected not dilution, but creative adaptation — a Buddhist tradition in dialogue with foreign influence while remaining true to its core principles.

Equally, Indian spiritual and philosophical ideas left their mark on Greek thought, from the anecdotal encounters of Pyrrho with Indian ascetics to possible thematic resonances with later Skeptic philosophers like Sextus Empiricus. These exchanges suggest a complex, bidirectional flow of ideas — one that enriched the philosophical traditions of both civilizations.

As these currents of exchange continued along the Silk Roads, the influence of this early East–West dialogue spread across Asia, leaving traces in Central Asia, China, and beyond. The Hellenistic–Indian contact zone thus served not only as a historical meeting point, but also as a launching ground for a far-reaching cultural legacy.

References and further reading

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

- Boardman, John, The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity, 1995, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691036809

- Tarn, W.W., The Greeks in Bactria and India, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108009416

- Thomas C. McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, 2001, Allworth, ISBN: 978-1581152036

- Pollitt, J. J., Art in the Hellenistic Age, 1986, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521276726

- Salomon, Richard, Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195099843

- Stoneman, Richard, The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks, 2019, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691154039

comments