Menander I and the Milindapañha: A Hellenistic king in Buddhist tradition

Menander I, known in Buddhist tradition as King Milinda, was one of the most prominent rulers of the Indo-Greek Kingdom during the 2nd century BCE. His reign marked a period of both territorial expansion and cultural fluorescence in the regions that now comprise Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwestern India. Unusually for a Greek monarch ruling in a non-Hellenistic context, Menander became immortalized not merely for his military prowess or political power, but for his philosophical engagement with the Buddhist tradition.

King Milinda ask questions. From Hutchinson’s story of the nations, 1920. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Milindapañha (“The Questions of Milinda”) is a classical Pāli text that records a fictionalized dialogue between Menander and the monk Nāgasena. This work stands as one of the most profound documents of Greco-Buddhist interaction, reflecting a deep cross-cultural engagement in matters of logic, metaphysics, and ethics. In it, the king poses challenging questions to the monk, who responds with clarity and parables drawn from Buddhist doctrine, particularly on the topics of non-self (anattā), rebirth, and liberation.

In this post, we explore Menander’s historical role as a Hellenistic king, his place in the Indo-Greek world, and his legacy through the Milindapañha.

Historical background

Menander I reigned during the mid-2nd century BCE, with scholarly estimates generally placing his rule between approximately 165 and 130 BCE. As one of the most powerful and successful Indo-Greek kings, he presided over an extensive territory that included parts of Bactria (in modern northern Afghanistan) and expanded deep into the northwestern Indian subcontinent, encompassing areas of present-day Pakistan and possibly as far east as Mathura. His reign represents the high point of Indo-Greek political influence and territorial reach.

Portrait of Menander I Soter, from his coinage. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

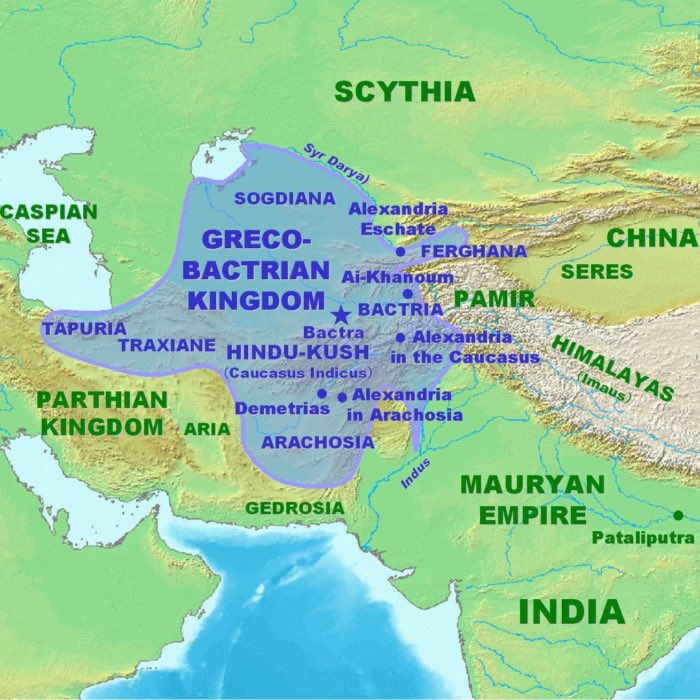

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, formed from the eastern territories of the Greco-Bactrian realm, was a product of Hellenistic expansion into Central and South Asia following the fragmentation of Alexander the Great’s empire. Under Menander’s rule, the kingdom not only expanded geographically but also stabilized politically. His military campaigns secured important trade routes and urban centers, allowing for sustained prosperity and cultural exchange.

The Indo-Greek Kingdoms in 100–150 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Diplomatically, Menander appears to have fostered an environment of relative inclusivity and integration. Greek, Iranian, and Indian cultural forms coexisted and interacted under his rule, supported by his bilingual coinage and possible patronage of diverse religious traditions. His ability to maintain authority over a multiethnic and multilingual population suggests both military competence and political acumen. These qualities, combined with his legacy as a philosopher-king in Buddhist tradition, distinguish Menander as a singular figure in the history of Greco-Indian interaction.

Menander as a Hellenistic ruler

Menander I was, in many respects, a quintessential Hellenistic monarch — an inheritor of the legacy of Alexander the Great and the Greco-Macedonian ethos of kingship. His reign is marked by a sophisticated use of coinage, urban development, and a remarkably flexible approach to governance in a multicultural environment.

Indian-standard coinage of Menander I. Obverse: dharmachakra with inscription: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ ΜΕΝΑΝΔΡΟΥ (“Of Saviour King Menander”). Reverse: Palm of victory, Kharoshthi legend Māhārajasa trātadasa Menandrāsa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Menander’s coinage is among the most prolific and revealing in the Indo-Greek world. He issued silver and bronze coins bearing Greek legends on one side and Kharosthi inscriptions on the other, a clear signal of his effort to communicate with both Greek and Indian subjects. The imagery on his coins features classical Hellenistic symbols such as Athena, Nike, and Zeus, as well as the epithet “Soter” (Savior), a title that conveyed his role as a protector and benefactor. These numismatic choices projected an image of a legitimate, divinely sanctioned ruler with appeal across cultural lines.

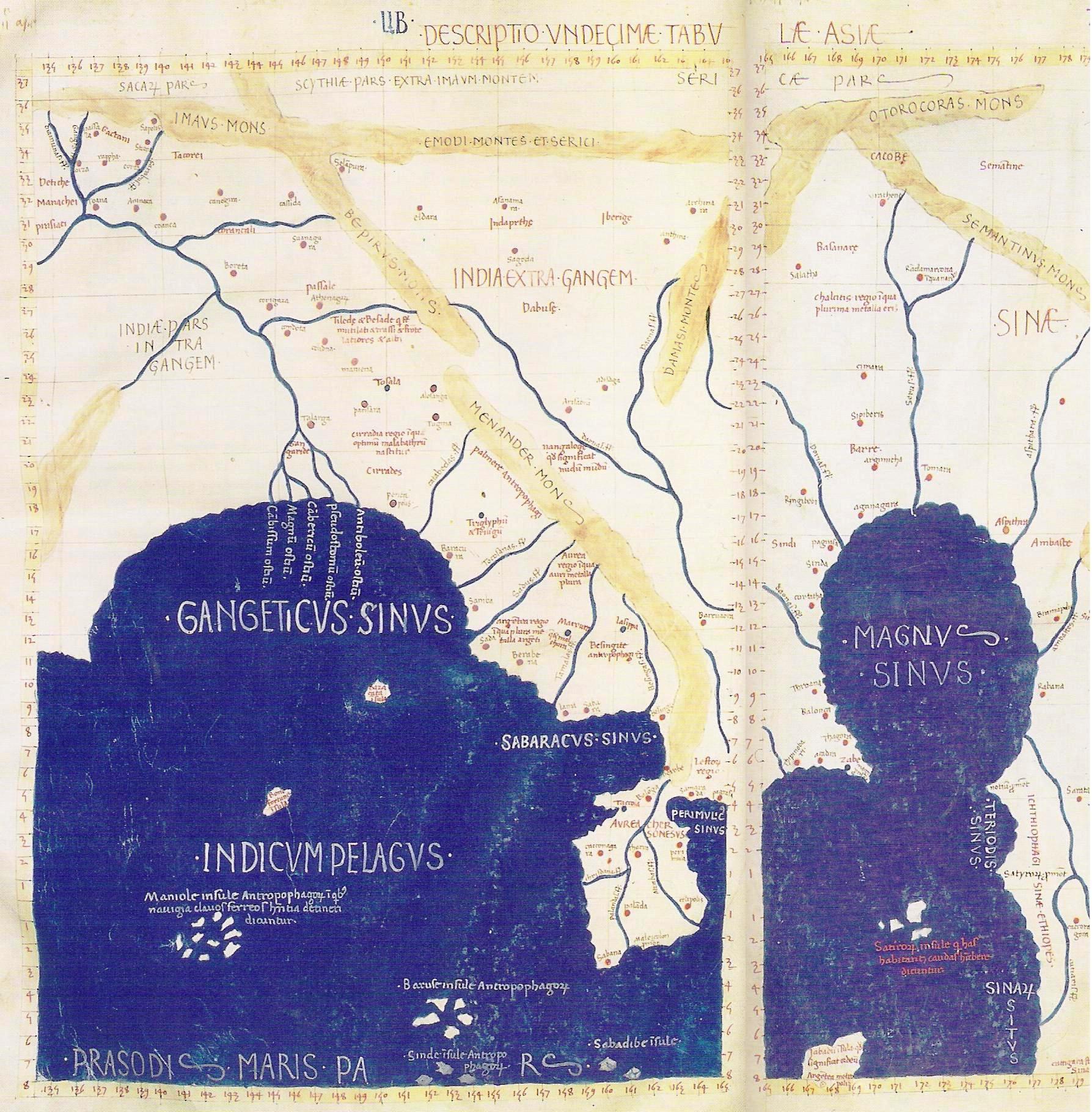

Detail of Asia in the Ptolemy world map. The “Menander Mons” are in the center of the map, at the east of the Indian subcontinent, right above the Malaysian Peninsula. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Urban development under Menander’s rule further underscores his Hellenistic identity. Although specific cities founded or refurbished by him remain uncertain, he likely contributed to the expansion and embellishment of key urban centers like Sagala (possibly modern Sialkot), which some traditions cite as his capital. These cities would have followed the model of the Hellenistic polis with theaters, marketplaces, and gymnasia — institutions designed not only for civic administration but for cultural integration and elite education.

Militarily, Menander was active in both defending and expanding his realm. Classical sources, such as Strabo and Plutarch, describe him as a formidable commander who campaigned far into the Indian subcontinent, possibly as far as the Ganges. His military success allowed him to stabilize borders and control key trade routes, particularly those facilitating Indo-Mediterranean commerce.

The Shinkot casket containing Buddhist relics was dedicated “in the reign of the Great King Menander”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Culturally, Menander’s governance reflects a pragmatic syncretism. While upholding Greek traditions of rulership, he also appears to have supported religious and philosophical plurality. His reign offered space for the coexistence of Greek deities, Indian religious practices, and Buddhist institutions. Such pluralism was not merely a political convenience but likely part of a broader Hellenistic worldview that valued cosmopolitanism and philosophical engagement.

The Butkara stupa as expanded during the reign of Menander I (2nd century BCE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In all these respects, Menander emerges as a ruler who not only embodied the ideals of Hellenistic kingship but also redefined them through engagement with Indian and Central Asian cultures, creating a model of rule that was adaptive, inclusive, and philosophically enriched.

The Milindapañha: structure and themes

The Milindapañha, or “The Questions of Milinda,” is a Buddhist text of great historical and philosophical importance that dramatizes a dialog between the Indo-Greek king Menander (Milinda) and the Buddhist monk Nāgasena. Structured as a question-and-answer format, the text presents a series of philosophical challenges posed by the king and answered with precision, analogy, and wit by the monk. It exemplifies the classical Indian tradition of dialogical pedagogy, while also echoing elements of the Greek dialectical method.

Composed originally in Pāli, with possible earlier versions in Prakrit or Sanskrit, the Milindapañha likely took form between the 1st century BCE and 1st century CE, several generations after Menander’s historical reign. Its composition reflects a syncretic intellectual atmosphere where Greek logical inquiry met Buddhist scholasticism. The text may have originated in the northwest Indian subcontinent, a region where Greco-Buddhist interaction was most intense.

Thematically, the Milindapañha engages deeply with foundational issues in Buddhist philosophy. Among its central concerns is the doctrine of non-self (anattā), which Nāgasena explains through a famous chariot analogy: just as a chariot is not any one of its parts but a functional whole, so too the self is a conventional designation for an ever-changing collection of physical and mental processes. Other key themes include the nature of karma and rebirth, the workings of causality and dependent origination, and the path to nirvana. Throughout, Nāgasena emphasizes clarity, rationality, and experiential insight over blind belief, thereby making Buddhist doctrine intellectually accessible to a Greek-influenced audience.

Beyond its philosophical content, the Milindapañha also serves as a cultural bridge. King Milinda is portrayed as an inquisitive, open-minded ruler, embodying both the Hellenistic spirit of rational inquiry and the Indian model of the righteous seeker. The text’s structure, combining dialog, metaphor, and debate, represents a meeting point between two great traditions of thought, making it one of the most remarkable documents of ancient intercultural exchange.

Milinda as a model of the philosophical king

The Milindapañha presents King Milinda not merely as a political authority, but as a deeply inquisitive and reflective figure — an embodiment of the ideal philosophical ruler. This portrayal bridges two traditions of political thought: the Greek ideal of the philosopher-king, famously articulated by Plato, and the Buddhist model of the Dharmarāja, the righteous king who governs in accordance with Dharma.

In the Hellenistic world, the philosopher-king was seen as a rare individual whose intellectual insight and moral discipline made him uniquely suited to rule justly. Plato envisioned such a ruler as someone who grasps eternal truths and applies them in the governance of society. King Milinda reflects this ideal in his relentless questioning of Nāgasena, his commitment to understanding subtle doctrines, and his willingness to be corrected. He does not simply assert authority but actively seeks wisdom, demonstrating the qualities of self-reflection and openness that were central to the Greek conception of philosophical kingship.

In parallel, the Buddhist tradition upholds the Dharmarāja as a monarch who uses his power to protect the moral order and promote the well-being of all beings. Milinda’s engagement with Nāgasena and his respectful reception of the Dharma align him with this archetype. He is portrayed as a ruler not only concerned with worldly governance but also with ethical responsibility and spiritual clarity.

The image of Milinda in the text is thus one of intellectual humility, rational curiosity, and moral aspiration. He embodies the intersection of reason and virtue, displaying a Socratic restlessness for truth alongside a Bodhisattva-like concern for ethical understanding. Whether or not the historical Menander truly converted to Buddhism, the literary Milinda functions as a powerful symbol of philosophical kingship across cultures — a reminder that the pursuit of wisdom transcends political boundaries and cultural origins.

Historical authenticity and literary construction

The question of whether Menander I truly converted to Buddhism remains a topic of scholarly debate. The Milindapañha presents a compelling image of a Greek king deeply engaged with Buddhist thought, and concludes with an account of his conversion and eventual attainment of arahantship (enlightenment). However, this narrative is part of a highly stylized dialogic text composed generations after Menander’s death, raising doubts about its historical accuracy. While early Buddhist tradition preserves a favorable memory of Menander, there is no definitive archaeological or epigraphic evidence such as inscriptions or dedicatory acts, confirming his personal conversion.

Scholars generally agree that the Milindapañha should be approached as a literary and pedagogical text rather than a historical biography. Its dialog format allowed Buddhist thinkers to explore complex doctrinal issues through a dramatic and intellectually engaging exchange. King Milinda functions as a foil for Nāgasena, representing a rational, inquisitive outsider whose probing questions allow for the clear exposition of Buddhist teachings. In this sense, the text serves as a vehicle for both philosophical instruction and cross-cultural legitimization.

Outside the Milindapañha, historical sources do attest to Menander’s political prominence and cross-cultural role. Classical writers such as Plutarch refer to him as a just and wise ruler, and numismatic evidence indicates a long and stable reign. His coinage, which continued to circulate after his death, and the wide geographical spread of his influence suggest a ruler who was widely respected. Yet none of these sources directly address his religious affiliations, leaving the question of his personal convictions unresolved.

Ultimately, the Milindapañha is best understood as a sophisticated work of philosophical literature, shaped by historical memory but not strictly constrained by it. It provides insight into how Buddhist communities of the time envisioned ideal kingship and intercultural dialogue, using Menander as a symbolic bridge between Greek rationalism and Buddhist wisdom.

Legacy and influence

Menander I’s legacy endured long after the decline of the Indo-Greek kingdoms, largely due to his distinctive position at the intersection of Hellenistic and Buddhist traditions. In Buddhist memory, he was not only remembered as a powerful monarch but also venerated as a wise ruler who earnestly sought truth and ethical understanding. Some Buddhist traditions even count him among those rare laypersons who attained enlightenment, highlighting the deep impression his image left on the religious imagination of the region.

The Milindapañha, as a text, had a particularly long and influential afterlife. Though not included in the main Pāli Canon, it was widely read and respected across Theravāda Buddhist cultures. Its clear structure and rational, dialogic style made it a favored tool for teaching complex Buddhist doctrines. The image of a foreign king, Greek in origin but intellectually and spiritually engaged, served as a model of how Buddhism could appeal beyond ethnic and cultural boundaries.

In Buddhist scholasticism, the Milindapañha came to occupy a unique position as a bridge text: not purely canonical, but intellectually authoritative. Its philosophical rigor and practical illustrations were cited in monastic curricula and commentarial literature, particularly in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. In this way, the figure of Milinda became emblematic of Buddhism’s capacity for dialogue, logic, and universal appeal.

More broadly, the enduring interest in both Menander and the Milindapañha speaks to the lasting significance of Greco-Buddhist philosophical exchange. Their story exemplifies the possibility of mutual transformation through intercultural contact. Rather than the dominance of one tradition over another, their encounter illustrates the productive tension and synthesis that arise when different intellectual and spiritual worlds meet. In this light, Menander’s legacy is not merely political or literary, but deeply philosophical: he remains a symbol of reasoned inquiry, ethical governance, and cultural openness.

Conclusion

Menander I occupies a unique position in ancient history as both a powerful Hellenistic monarch and a philosophical figure embedded in Buddhist tradition. Politically, he consolidated and expanded the Indo-Greek realm, maintaining stability and fostering cultural integration across a multiethnic empire. Philosophically, his enduring image as King Milinda in the Milindapañha presents him as a ruler devoted to rational inquiry, ethical deliberation, and respectful engagement with Buddhist doctrine.

The dialog between Menander and Nāgasena exemplifies the rich potential of Greco-Indian exchange — a meeting not only of political powers but of philosophical traditions. The Milindapañha reveals how Buddhist thinkers could employ Hellenistic forms of reasoning to articulate their doctrines while portraying a foreign ruler as an ideal inquirer, capable of grasping the subtleties of Dharma. This intercultural moment underscores the permeability of civilizational boundaries and the transformative possibilities of genuine dialogue.

Yet many questions remain open. To what extent did the historical Menander genuinely embrace Buddhism? Was the text a faithful memory or a carefully crafted pedagogical fiction? And how far-reaching was the influence of such Greco-Buddhist syntheses in later South and Central Asian developments? These inquiries invite further exploration into the complex web of cultural, religious, and intellectual interactions that shaped the ancient world.

References and further reading

- Stoneman, Richard, The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks, 2019, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691154039

- Thomas C. McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, 2001, Allworth, ISBN: 978-1581152036

- Lamotte, Étienne, History of Indian Buddhism, 1988, Peeters Pub & Booksellers, ISBN: 978-9068311006

- Rhys Davids, T. W., The Questions of King Milinda, 2025, BPS Pariyatti Editions, ISBN: 978-1681727813

- Tarn, W.W., The Greeks in Bactria and India, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108009416

comments