The illusion of free will and Buddhist ethics

The question of free will has occupied Western philosophy for millennia, with debates oscillating between determinism, compatibilism, and libertarian notions of human agency. In recent decades, neuroscience has added a new dimension to the discussion, providing experimental data that challenges the idea of conscious, autonomous decision-making. In a parallel but historically independent development, Buddhist thought, particularly in its earliest formulations by Siddhartha Gautama, has long denied the existence of a permanent self (atman) and has articulated an ethical system based not on absolute agency but on conditioned volition (cetana). In this post, we examine how contemporary neuroscientific critiques of free will resonate with Buddhist insights and how Buddhist ethics provides a coherent and practical framework that transcends the metaphysical dilemma of free will.

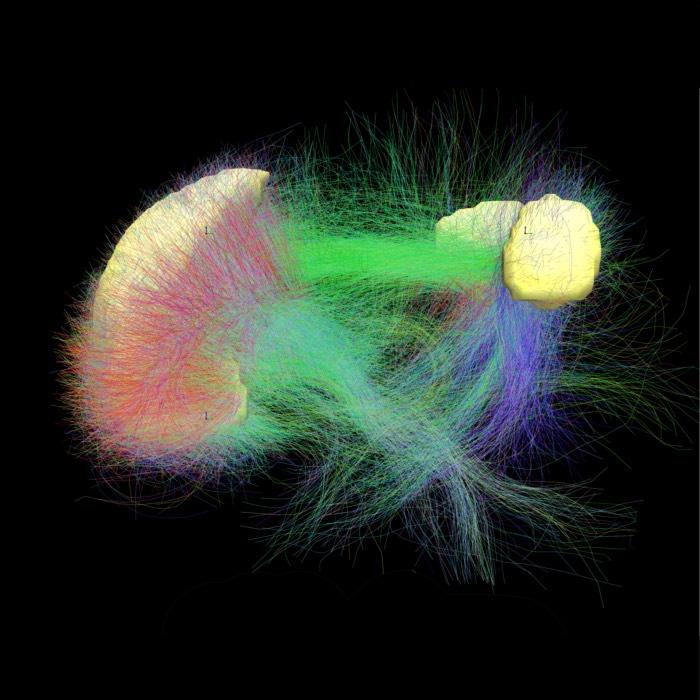

Some areas of the human brain implicated in mental disorders that might be related to free will. Area 25 refers to Brodmann’s area 25, related to major depression. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Neuroscientific challenges to free will

Pioneering studies by Benjamin Libet et al. (1983) demonstrated that unconscious brain activity, the “readiness potential” (“Bereitschaftspotential”), precedes the conscious intention to act by several hundred milliseconds. In Libet’s experiments, participants were asked to flex their wrist at a moment of their choosing while noting the time at which they became aware of their intention to move. The EEG data revealed that the brain had already initiated the motor process before the conscious intention was reported.

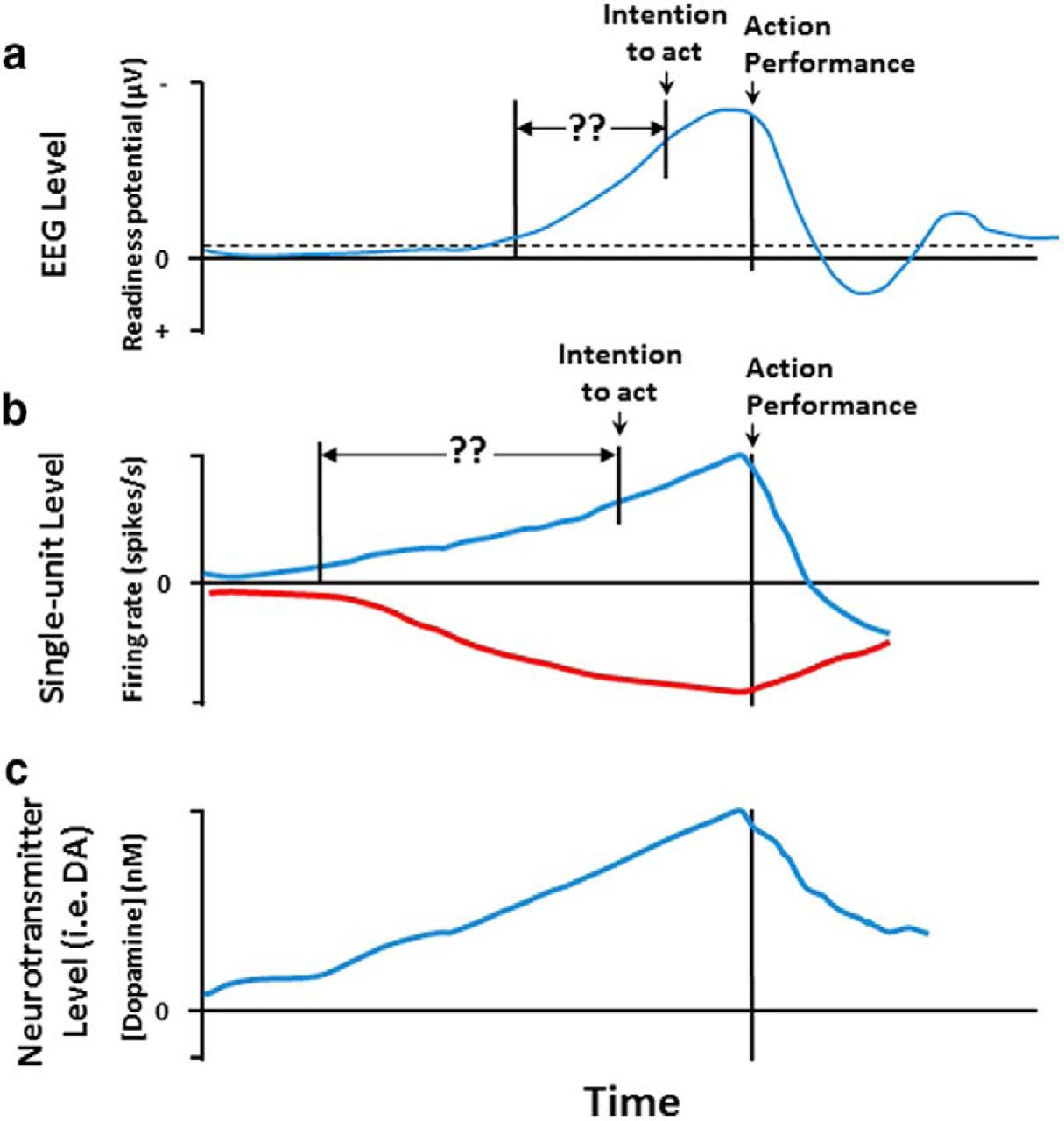

Typical recording of the Bereitschaftspotential that was discovered by Kornhuber and Deecke in 1965. Benjamin Libet investigated whether this neural activity corresponded to the “felt intention” (or will) to move of experimental subjects. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Subsequent studies have refined and expanded Libet’s findings. For instance, Soon et al. (2008) used fMRI to predict participants’ decisions several seconds before they became consciously aware of them. These results suggest that what we experience as “free will” may actually be a post hoc rationalization of decisions initiated unconsciously.

While some philosophers have argued for nuanced interpretations of these findings (e.g., Mele, 2009), the general consensus in cognitive neuroscience increasingly favors the view that conscious free will is, at best, limited and, at worst, illusory.

On several different levels, from neurotransmitters through neuron firing rates to overall activity, the brain seems to “ramp up” before movements. This image depicts the readiness potential (RP), a ramping-up activity measured using EEG. The onset of the RP begins before the onset of a conscious intention or urge to act. Some have argued that this indicates the brain unconsciously commits to a decision before consciousness awareness. Others have argued that this activity is due to random fluctuations in brain activity, which drive arbitrary, purposeless movements. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0); original work by Fifel (2018)ꜛ (there: Figure 1)

Buddhist views on volition and non-self

Siddhartha Gautama’s teaching on anattā (non-self) challenges the notion of a central, autonomous agent directing actions. In texts such as the Anattā-lakkhaṇa Sutta (SN 22.59), Siddhartha analyzes the Five Aggregates (khandha) — form, feeling, perception, mental formations, and consciousness — demonstrating that none of them, individually or collectively, constitute a self.

In the context of action, Buddhism places emphasis on cetana, usually translated as “volition” or “intention.” According to the Aṅguttara Nikāya (AN 6.63), “It is volition, monks, that I call kamma; for having willed, one acts by body, speech, and mind.” Volition is thus seen as a conditioned process arising within a causal nexus, not the expression of a sovereign free will. Actions are neither uncaused nor entirely predetermined but emerge from a complex interplay of causes and conditions (paṭiccasamuppāda, dependent origination).

This view allows for ethical responsibility without requiring metaphysical free will. Actions have consequences (karma), but the agent is not a fixed entity; rather, “agency” is a process, a flowing configuration of conditions.

Compatibility between neuroscience and Buddhist ethics

The convergence between neuroscience and Buddhism lies in the recognition that human behavior arises from complex, often unconscious, processes. Yet this convergence does not entail nihilism or fatalism. In Buddhism, the absence of a fixed self does not eliminate ethical responsibility; instead, it relocates responsibility to the dynamic interplay of mind and action.

Modern neuroscience suggests that although unconscious processes initiate actions, conscious awareness can still influence behavior by modifying habits and predispositions over time (Schurger et al., 2012). Similarly, Buddhist practice aims at cultivating skillful mental habits (kusala cetanā) through mindfulness (sati) and ethical discipline (sīla), thereby shaping future actions and experiences.

Thus, both perspectives emphasize that while instantaneous “free will” may be an illusion, longer-term self-regulation and transformation are possible. Ethical practice, in this view, becomes a matter of training conditions rather than expressing an uncaused inner essence.

Critical reflections

One important distinction must be made: Western debates often hinge on metaphysical definitions of freedom and moral responsibility, while Buddhism focuses pragmatically on the alleviation of suffering (dukkha). The Buddhist framework sidesteps many of the traditional dilemmas by refusing to reify the self or will in the first place. Instead, it emphasizes conditionality, impermanence (anicca), and the practical possibility of cultivating wholesomeness.

Moreover, while Libet-style experiments point to the unconscious origins of action, they do not fully address complex, reflective decisions that unfold over time, involving deliberation, value judgments, and self-cultivation. Buddhist practice is oriented precisely toward this longer arc of transformation, where mindfulness and wisdom (paññā) modulate habitual tendencies.

In this respect, Buddhist ethics may offer a more realistic and compassionate account of moral responsibility than frameworks rooted in rigid notions of autonomous free will.

Conclusion

The convergence between neuroscience and Buddhism suggests that the traditional notion of free will as absolute self-causation is untenable. Yet, rather than resulting in nihilism, the Buddhist ethical framework offers a path of mindful cultivation, emphasizing responsibility as an emergent, conditioned process. Recognizing the illusion of free will does not absolve one from ethical action; it invites a deeper understanding of human behavior as dynamic and transformable, in accordance with the fundamental principles of interdependence and impermanence.

References and further reading

- Benjamin Libet, Curtis A. Gleason, Elwood W. Wright, Dennis K. Pearl, Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential): The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act, 1983, Brain, 106(3), 623-642, doi: 10.1093/brain/106.3.623ꜛ

- Mele, A. R., Effective intentions: The power of conscious will, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780199869909, doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195384260.001.0001ꜛ

- Soon, C. S., Brass, M., Heinze, H. J., & Haynes, J. D., Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain, 2008, Nature Neuroscience, 11(5), 543-545, doi: 10.1038/nn.2112ꜛ

- Schurger, A., Sitt, J. D., & Dehaene, S., An accumulator model for spontaneous neural activity prior to self-initiated movement, 2012, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(42), E2904-E2913, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210467109ꜛ

- Karim Fifel, Readiness Potential and Neuronal Determinism: New Insights on Libet Experiment, 2018, Journal of Neuroscience, 38 (4) 784-786; doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3136-17.2017ꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Neuroscience of free willꜛ

comments