Plasma instabilities as dynamical departures from equilibrium

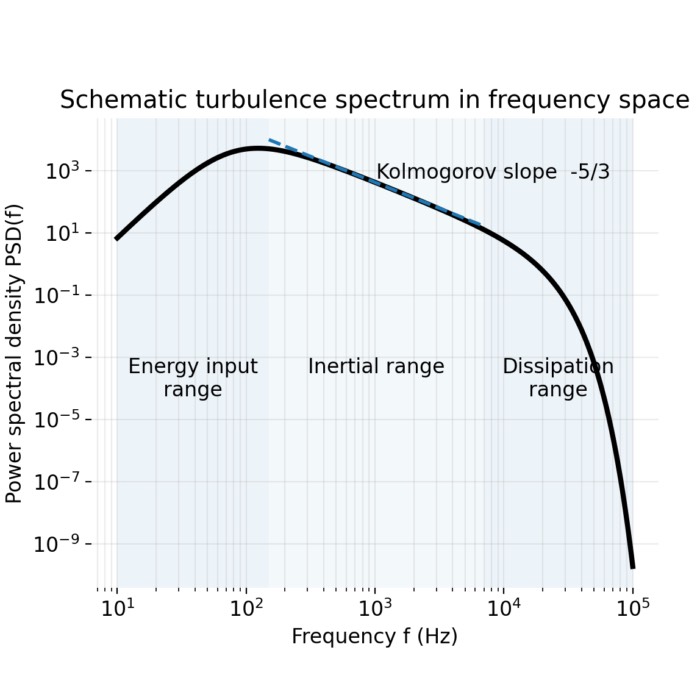

Plasma instabilities mark the transition from passive wave propagation to active energy conversion. While plasma waves describe small amplitude perturbations of a stable equilibrium, instabilities arise when the equilibrium itself is unable to support certain perturbations, leading to exponential growth in time. In mathematical terms, this corresponds to dispersion relations whose solutions acquire a positive imaginary part of the frequency. Physically, instabilities tap free energy stored in gradients, relative flows, or anisotropic particle distributions and convert it into electromagnetic fields and particle motion.

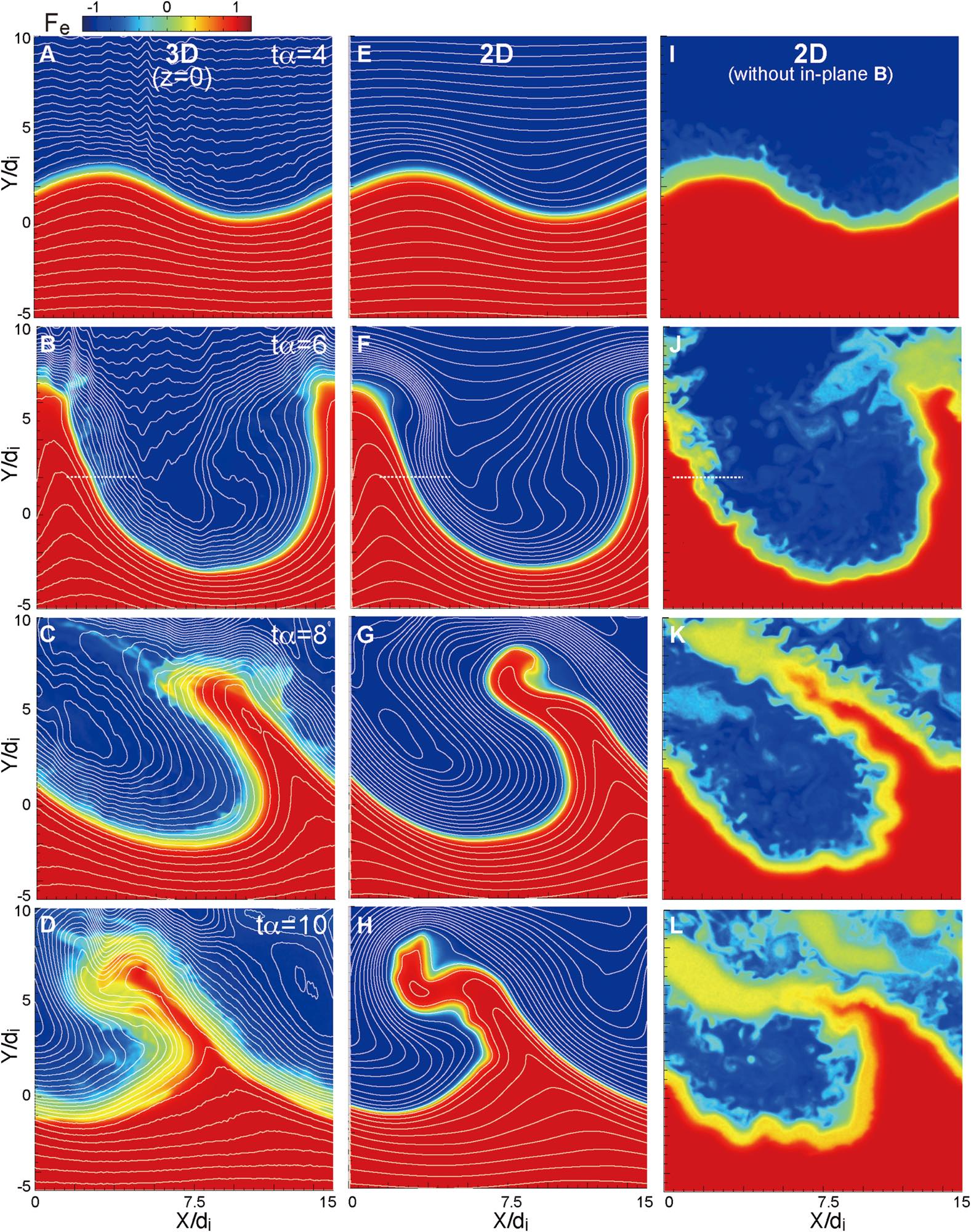

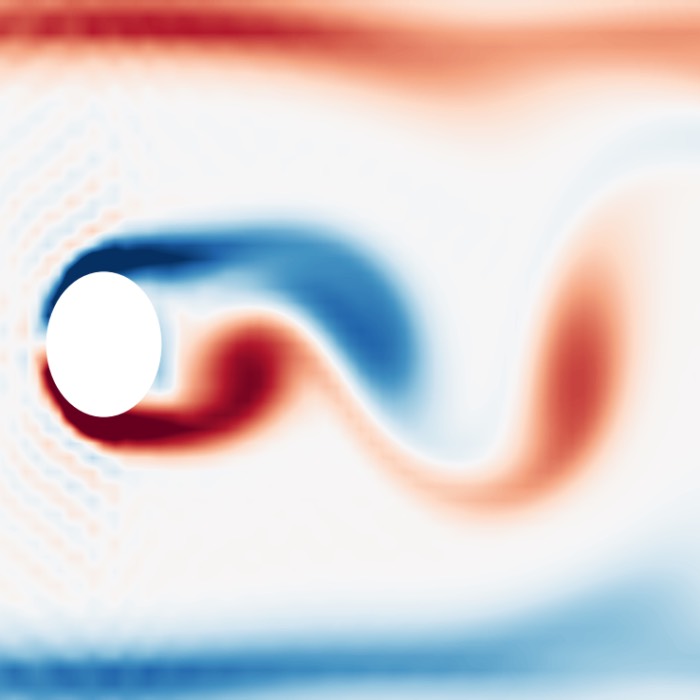

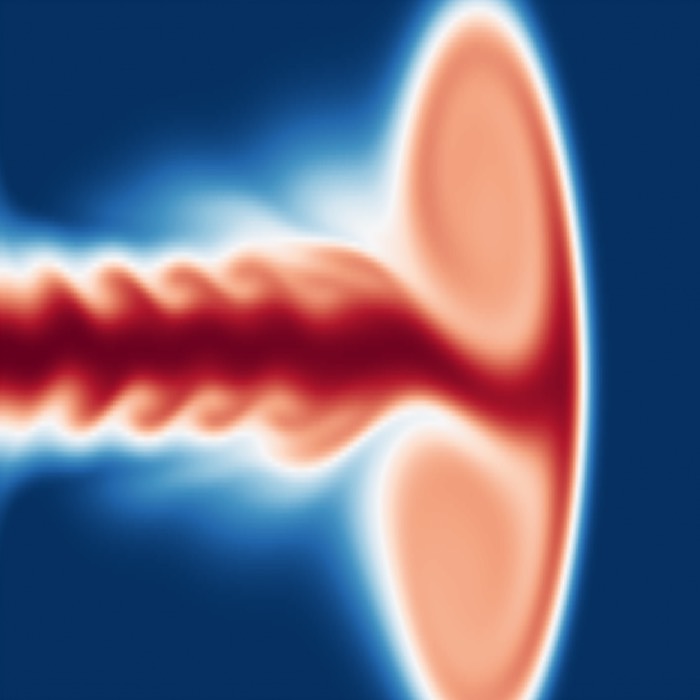

Figure 1 (panels a–l) from Nakamura et al. (2022) shows the time evolution of plasma mixing driven by the magnetopause Kelvin–Helmholtz instability. Plasma instabilities such as the Kelvin–Helmholtz mode facilitate the transport of mass, momentum, and energy across boundary layers that would otherwise remain impermeable. Here, the progressive roll-up of the shear layer into vortices and the associated deformation of magnetic field lines demonstrate the nonlinear growth of the instability and its role in enabling cross-boundary plasma transport. Panels a–d display results from a fully 3-D simulation, panels e–h the corresponding 2-D run, and panels i–l a 2-D run without an initial in-plane magnetic field. Colors represent the mixing measure $F_e = (n_{e1}-n_{e2})/(n_{e1}+n_{e2})$, which quantifies the degree of interpenetration between two initially distinct electron populations. White curves in the 3-D and corresponding 2-D cases indicate contours of the out-of-plane vector potential, corresponding to in-plane magnetic field lines. The progressive roll-up of the shear layer into vortices and the associated deformation of magnetic field lines demonstrate the nonlinear growth of the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability and its role in enabling cross-boundary plasma transport. Source: Nakamura et al. (2022)ꜛ, Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences (license: CC BY 4.0).

In space plasmas, instabilities are ubiquitous. Velocity shear at magnetopause boundaries, density stratification in gravitational fields, and counter streaming particle populations all provide sources of free energy. Instabilities play a decisive role in plasma transport, turbulence generation, boundary layer formation, and plasma heating. They are therefore not pathological special cases, but rather fundamental mechanisms by which plasmas evolve away from idealized equilibria.

Linear stability analysis and growth rates

The mathematical framework for plasma instabilities is linear stability theory. One considers a stationary equilibrium state and introduces infinitesimal perturbations of the form

\[\propto \exp[i(\mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{x} - \omega t)].\]The resulting dispersion relation generally yields complex frequencies

\[\omega = \omega_r + i\gamma,\]where $\omega_r$ is the real oscillation frequency and $\gamma$ the growth rate. A positive $\gamma$ indicates an unstable mode.

In fluid theory, instabilities arise when restoring forces such as pressure gradients or magnetic tension are insufficient to counteract driving terms associated with gravity, shear flows, or inertia. In kinetic theory, instabilities are associated with resonant wave particle interactions and non monotonic velocity distributions. The same physical instability often admits both a fluid and a kinetic description, depending on the spatial and temporal scales involved.

Rayleigh Taylor instability in plasmas

The Rayleigh Taylor instability occurs when a heavier fluid is supported against gravity by a lighter one. In plasmas, gravity can be replaced or supplemented by effective forces such as centrifugal acceleration or magnetic curvature. Consider a plasma stratified in the vertical direction $z$ under a constant acceleration $\mathbf{g} = -g \hat{z}$, with density decreasing upward.

In the incompressible fluid approximation, linearizing the momentum and continuity equations leads to the classical dispersion relation

\[\omega^2 = - g k \frac{\rho_2 - \rho_1}{\rho_2 + \rho_1},\]where $\rho_1$ and $\rho_2$ are the densities of the lower and upper layers. If the heavier fluid lies above the lighter one, $\omega^2$ becomes negative, implying purely imaginary $\omega$ and exponential growth.

In magnetized plasmas, magnetic tension introduces a stabilizing term. For perturbations with wavevector perpendicular to the magnetic field, the dispersion relation generalizes to

\[\omega^2 = - g k \frac{\Delta \rho}{\rho} + k^2 v_A^2,\]where $v_A$ is the Alfvén speed. Short wavelength modes are stabilized by magnetic tension, while long wavelength modes remain unstable. This balance is central to plasma confinement, astrophysical jets, and magnetospheric boundary layers.

Kelvin-Helmholtz instability in magnetized shear flows

The Kelvin-Helmholtz instability arises from velocity shear between adjacent plasma regions. Consider two semi infinite plasmas with uniform velocities $\mathbf{U}_1$ and $\mathbf{U}_2$, separated by a planar interface. In the simplest incompressible hydrodynamic case, linear analysis yields the dispersion relation

\[\omega = \mathbf{k}\cdot\frac{\mathbf{U}_1 + \mathbf{U}_2}{2} \pm \sqrt{\left(\mathbf{k}\cdot\frac{\mathbf{U}_1 - \mathbf{U}_2}{2}\right)^2}.\]Any finite velocity difference leads to instability for perturbations aligned with the flow.

In magnetized plasmas, magnetic tension again modifies the result. For a magnetic field parallel to the flow, the dispersion relation becomes

\[\left(\omega - \mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{U}_1\right)^2 + \left(\omega - \mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{U}_2\right)^2 = k^2 v_A^2.\]If the velocity shear is smaller than twice the Alfvén speed, magnetic tension suppresses the instability. This criterion explains why Kelvin-Helmholtz waves develop preferentially at the flanks of planetary magnetopauses, where the magnetic field orientation and flow geometry are favorable.

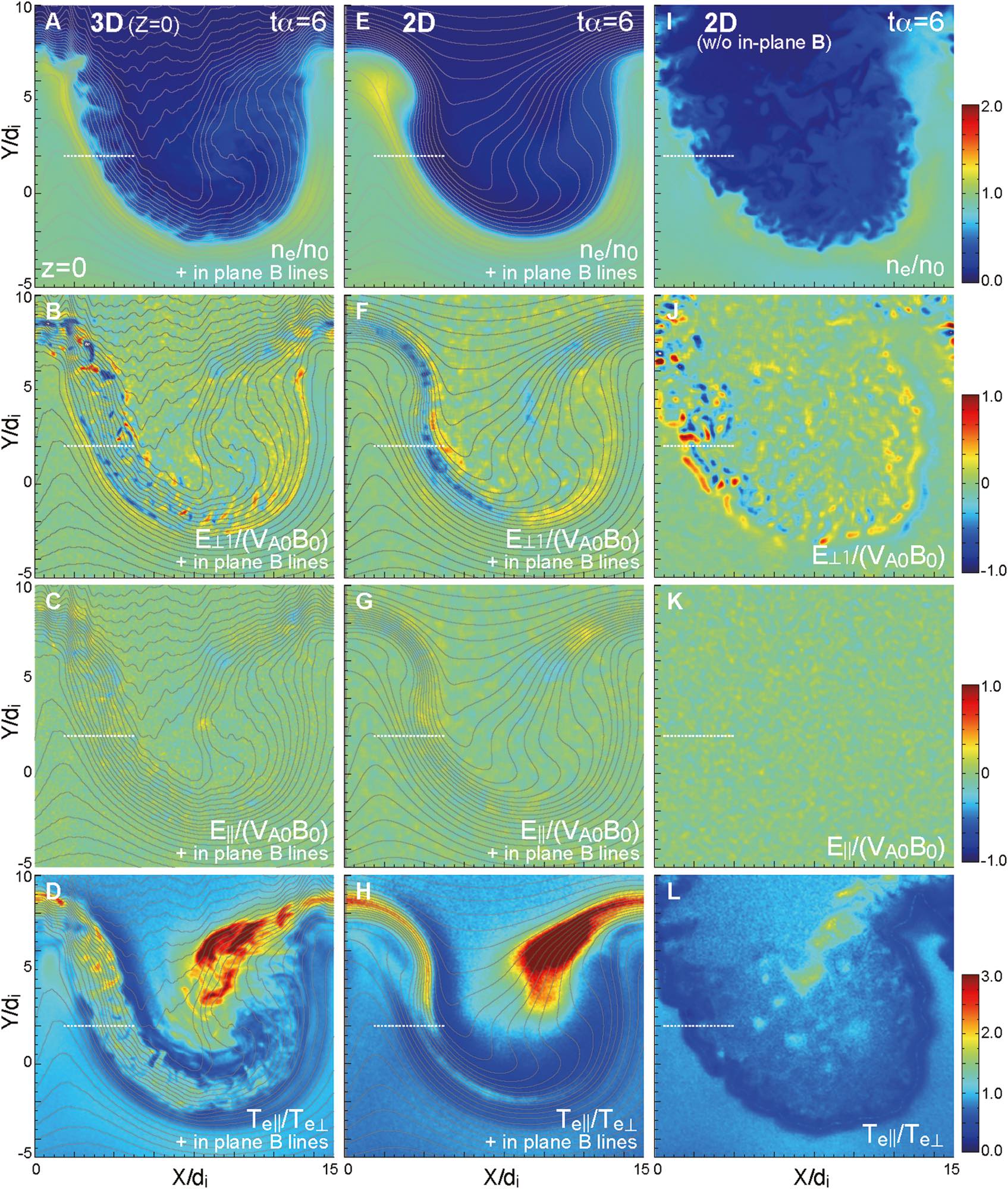

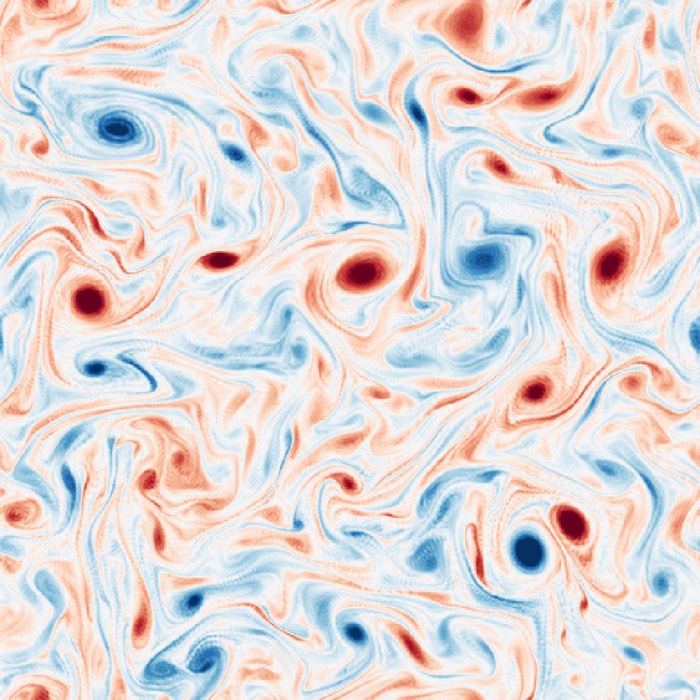

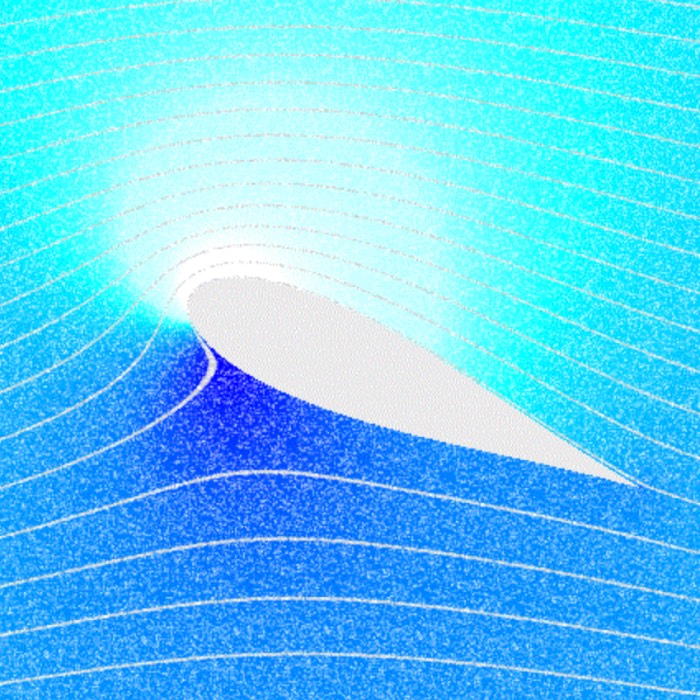

Figure 2 (panels a–l) from Nakamura et al. (2022) illustrates the electromagnetic and kinetic signatures accompanying Kelvin–Helmholtz–driven plasma mixing. Shown are color contours in the x–y plane of electron density $n_e$, the perpendicular and parallel components of the electric field, and the electron temperature anisotropy ratio $T_{e\parallel}/T_{e\perp}$ at a fixed nonlinear stage of the instability. As in Figure 1, panels a–d correspond to the 3-D simulation, panels e–h to the equivalent 2-D case, and panels i–l to a 2-D run without initial in-plane magnetic fields. Gray curves denote contours of the out-of-plane vector potential, representing magnetic field lines. The emergence of strong parallel electric fields and pronounced temperature anisotropies highlights the coupling between macroscopic Kelvin–Helmholtz vortices and kinetic-scale processes, demonstrating how this instability facilitates energy conversion and irreversible plasma transport across the magnetopause. Source: Nakamura et al. (2022)ꜛ, Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences (license: CC BY 4.0).

Two stream instability and kinetic free energy

The two stream instability is fundamentally kinetic in nature and has no true analogue in single fluid MHD. It arises when two particle populations stream through each other with relative velocity $U$. Consider a one dimensional plasma with two cold electron beams. The linearized Vlasov Poisson system yields the dispersion relation

\[1 - \frac{\omega_{p}^2}{(\omega - kU)^2} - \frac{\omega_{p}^2}{(\omega + kU)^2} = 0.\]This equation admits solutions with positive imaginary parts of $\omega$ when the drift velocity exceeds a threshold. Physically, perturbations extract energy from the relative drift, leading to exponential growth of electric field fluctuations.

In warm plasmas, the instability is regulated by velocity spread and Landau damping. The two stream instability is closely related to beam driven instabilities observed in the solar wind, foreshock regions, and astrophysical plasmas.

Instabilities as wave growth

From a unified perspective, plasma instabilities can be viewed as waves whose dispersion relation has crossed into the complex plane. The same mathematical machinery used to describe plasma waves therefore applies, with the crucial difference that the system no longer supports oscillatory solutions but amplifies perturbations instead.

In many cases, instabilities initially grow linearly and later saturate through nonlinear effects, mode coupling, or particle trapping. This nonlinear phase often seeds turbulence and leads to irreversible plasma heating, making instabilities a primary driver of plasma evolution rather than a transient phenomenon.

Role in space plasma dynamics

Plasma instabilities govern the structure and dynamics of many space plasma environments. Rayleigh Taylor type modes contribute to interchange instabilities in magnetospheres. Kelvin-Helmholtz waves facilitate plasma transport across magnetopauses. Two stream and beam instabilities generate electrostatic turbulence and particle scattering. Together, these mechanisms control how plasmas redistribute energy and momentum under nonequilibrium conditions.

Understanding plasma instabilities therefore completes the picture begun with plasma waves. While waves describe how plasmas respond to perturbations, instabilities explain how plasmas reorganize themselves when equilibrium can no longer be maintained.

Update: This post was originally drafted in 2020 and archived during the migration of this website to Jekyll and Markdown. In January 2026, I substantially revised and expanded the content and decided to re-release it in an updated and technically consistent form, while keeping its original chronological context.

References and further reading

- Wolfgang Baumjohann and Rudolf A. Treumann, Basic Space Plasma Physics, 1997, Imperial College Press, ISBN: 1-86094-079-X

- Treumann, R. A., Baumjohann, W., Advanced Space Plasma Physics, 1997, Imperial College Press, ISBN: 978-1-86094-026-2

- Stix, T. H., Waves in Plasmas, 1997, American Institute of Physics, ISBN: 978-0883188590

- Nakamura TKM, Blasl KA, Liu Y-H and Peery SA, Diffusive Plasma Transport by the Magnetopause Kelvin-Helmholtz Instability During Southward IMF, 2022, Front. Astron. Space Sci. 8:809045. doi: 10.3389/fspas.2021.809045ꜛ

- Francis F. Chen, Introduction to plasma physics and controlled fusion, 2016, Springer, ISBN: 978-3319223087

- Swanson, D. G., Plasma waves, 1989, Academic Press, ISBN: 978-0126789553

- Nicholson, Introduction to Plasma Theory, 1992, Krieger Publishing Company, ISBN: 978-0894646775

- Gary, S. P., Theory of space plasma microinstabilities, 1993, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521431675

- Davidson, R. C., Methods in nonlinear plasma theory, 1972, Academic Press, ISBN: 978-0124315365

- Thomas J. M. Boyd & J. J. Sanderson, The Physics of Plasmas, 2003, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521459129

- Kivelson, M. G., Russell, C. T. (eds.), Introduction to space physics, 1995, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521457149

- Landau, L. D., On the vibrations of the electronic plasma, 1946/1965, Collected Papers of L.D. Landau, Pergamon, Pages 445-460, ISBN 9780080105864

comments