The Four Noble Truths: The heart of the Buddha’s teaching

The Four Noble Truths (Pāli: cattāri ariya saccāni; Sanskrit: catvāri ārya satyāni) stand as the foundation of Buddhist philosophy and practice. These truths, articulated by Siddhartha Gautama in his first sermon after attaining enlightenment, encapsulate both the diagnosis of human suffering and the path to its cessation. Rather than being abstract philosophical musings, the Four Noble Truths provide a pragmatic framework for understanding existence and navigating the path toward liberation. In this post, we explore the depth and significance of each truth, their interconnections, and their relevance in Buddhist thought and practice.

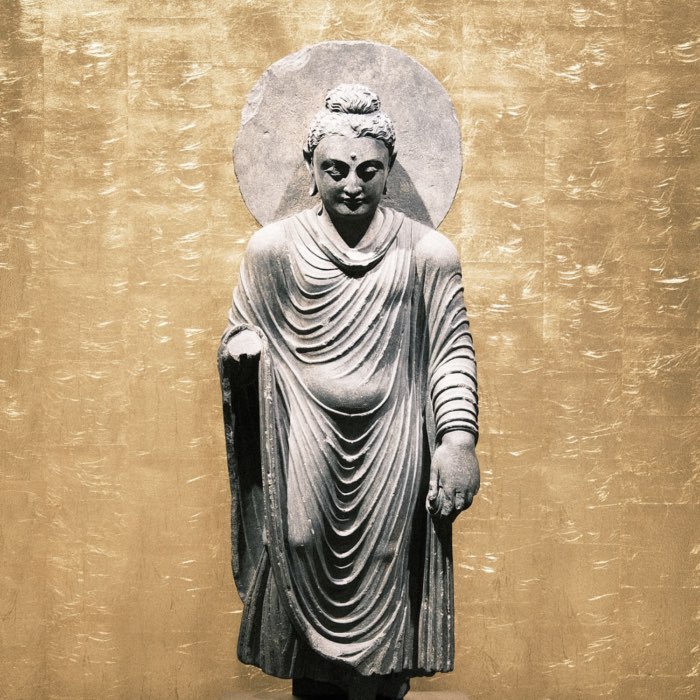

The eight miracles, Eastern India, Nalanda, 10th - 11th c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin in 2023. This Eastern Indian stela depicts the eight miracles of Buddha’s life: his birth in Lumbini (l. bottom); enlightenment in Bodhgaya (centre); first sermon in Sarnath (l. top); conversion of people in Shravasti (r. top); taming a wild elephant in Rajagriha (r. middle); descending from Tushita Heaven in Sankasya (l. middle); a monkey donating honey in Vaishali (r. bottom); and death in Kushinagara (top). In his first sermon in Sarnath, Siddhartha Gautama expounded the Four Noble Truths, laying the foundation for Buddhist philosophy and practice.

The eight miracles, Eastern India, Nalanda, 10th - 11th c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin in 2023. This Eastern Indian stela depicts the eight miracles of Buddha’s life: his birth in Lumbini (l. bottom); enlightenment in Bodhgaya (centre); first sermon in Sarnath (l. top); conversion of people in Shravasti (r. top); taming a wild elephant in Rajagriha (r. middle); descending from Tushita Heaven in Sankasya (l. middle); a monkey donating honey in Vaishali (r. bottom); and death in Kushinagara (top). In his first sermon in Sarnath, Siddhartha Gautama expounded the Four Noble Truths, laying the foundation for Buddhist philosophy and practice.

“It is through not realizing, through not penetrating, the Four Noble Truths, that this long course of birth and death (samsāra) has been carried on and endured by me — and by you as well. What are these four?

- The noble truth of suffering,

- The noble truth of the origin of suffering,

- The noble truth of the cessation of suffering, and

- The noble truth of the path of practice leading to the cessation of suffering.

But now, since these truths have been realized and penetrated, the craving for existence has been cut off, that which leads to further becoming has been destroyed, and there is no more fresh becoming.”

— DN16

Understanding the Noble Truths

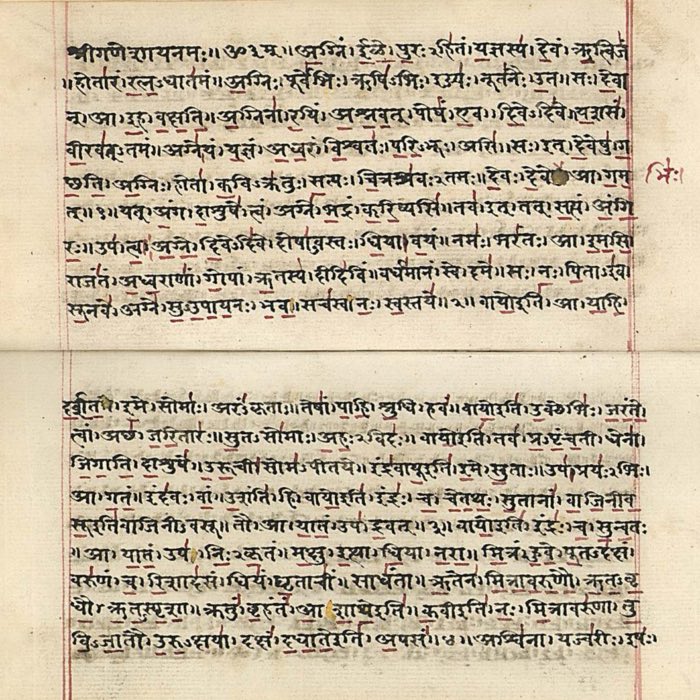

The Four Noble Truths emerged within the broader context of ancient Indian religious and philosophical thought, which was already rich with ideas about suffering, liberation, and the cycle of rebirth (samsāra). While other Indian traditions, such as early Brahmanism and the Upanishadic schools, sought liberation through ritual, asceticism, or metaphysical insight, the Buddha’s formulation of the Four Noble Truths provided a radically practical, empirical approach.

Historically, Siddhartha Gautama, later known as the Buddha, formulated the Four Noble Truths following his profound meditative insight under the Bodhi tree. After years of spiritual seeking and experimenting with extreme ascetic practices, he realized that neither indulgence nor self-mortification leads to true liberation. Upon attaining enlightenment, he articulated the Four Noble Truths in his first sermon, the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, as the essence of what he had discovered.

These truths are not meant to be taken as isolated dogmas, but as a concentrated summary of a much broader philosophy. They encapsulate the structure of the Buddha’s insight into the nature of suffering and liberation, but they are supported and elaborated by extensive teachings on ethics, mental training, and wisdom. In this sense, the Four Noble Truths function as the entry point into a vast and nuanced philosophical system centered on transformation through self-understanding and direct experience.

The structure of the Four Noble Truths mirrors that of ancient Indian medical diagnosis: identify the disease, find its cause, determine its cure, and outline the treatment. This analogy is not coincidental; the Buddha positioned himself as a physician of the human condition, diagnosing suffering and prescribing a path to healing.

Philosophically, the Four Noble Truths establish a worldview grounded in impermanence (anicca), non-self (anattā), and interdependent origination (paṭicca-samuppāda). These ideas marked a significant departure from the prevailing notions of an eternal soul (ātman) and a permanent cosmic order (ṛta), which underpinned much of Brahmanical thinking.

Centrally, the Four Noble Truths are not simply one teaching among many. They form the nucleus of all subsequent Buddhist doctrine. Every school of Buddhism, from Theravāda to Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna, regards them as foundational. They are the framework within which the concepts of karma, rebirth, meditation, and enlightenment are understood and practiced.

The term “cattāri ariya saccāni”

The Pāli term cattāri ariya saccāni (Sanskrit: catvāri ārya satyāni) is often translated as “The Four Noble Truths”, but this phrasing can be misleading. The word ariya (Sanskrit: ārya), typically rendered as “noble”, does not describe the truths themselves. Instead, it refers to the individuals who have directly realized and internalized these truths.

In this context, ariya points to those who have reached a level of spiritual awakening, such as Arhats, individuals who have attained transcendent wisdom (Prajñā Pāramitā). The truths are thus not “noble” by their own nature, but are truths for the spiritually noble, that is, for those who see reality clearly and unflinchingly. A more accurate translation might be: “Four truths for the spiritually noble” or “Four truths seen by the noble ones”.

This distinction emphasizes that the Four Noble Truths are not religious dogma to be believed, but insights to be realized through experience. They outline a universal structure underlying suffering and liberation, accessible to anyone who sincerely undertakes the path.

The First Noble Truth: Dukkha - The reality of suffering

“Life in the cycle of existence (samsāra) is suffering (dukkha): birth is suffering, aging is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering; sorrow, lamentation, pain, and despair are suffering. Association with the unloved is suffering, separation from the loved is suffering, not getting what one desires is suffering. In short, the five aggregates of clinging — the five skandhas — are suffering.”

— SN 56.11

The first noble truth asserts that suffering (dukkha) is an inherent characteristic of conditioned existence. Buddhism does not merely refer to suffering as physical pain or emotional distress but extends it to include a deeper existential dissatisfaction. Dukkha is not limited to extreme suffering but pervades all experiences due to the impermanent nature of reality. Buddhist texts categorize suffering into three broad types:

- Ordinary suffering (dukkha-dukkha): This includes physical and mental pain, such as illness, aging, death, grief, and despair.

- Suffering due to change (vipariṇāma-dukkha): Even pleasurable experiences are marked by suffering because they are fleeting. The loss of happiness, relationships, or possessions inevitably leads to distress.

- Suffering due to conditioned existence (saṅkhāra-dukkha): This is the most subtle and pervasive form of suffering, arising from the very nature of existence within samsāra (the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth). It stems from the fundamental unsatisfactoriness of conditioned experience.

Life is dukkha (not satisfying) because people cling (upādāna) to the five skandhas (aggregates) and to the resulting illusion of fixed and permanent cores of being, including the belief in a self-sufficient and independently existing personality (pudgala). According to Siddhartha Gautama, this attachment arises from ignorance (avijjā) of the true nature of reality. He identified three fundamental marks of existence (tilakkhaṇa) that apply to all phenomena (dharmas) to which we become attached:

- anicca: All things are impermanent. Everything is in constant flux and nothing is eternal.

- anattā: All things are insubstantial. There is no enduring, independent self. This lack of inherent identity is deeply connected to anicca, as the transient nature of all phenomena ensures that nothing possesses a fixed or permanent essence. Together, they reveal the interconnected and ever-changing fabric of existence.

- dukkha: All things are ultimately unsatisfactory. This is because sentient beings cling to things that are impermanent and lack an inherent core. While such attachments may bring fleeting moments of pleasure, they inevitably lead to dissatisfaction as they cannot provide lasting fulfillment.

Because we do not perceive reality as it actually is – due to the lack of an inherent core and due to constantly ongoing change, all things are processes rather than fixed entities, and all things are interdependent rather than isolated entities — we cling to the illusion of a permanent self and a stable world. This clinging is the root of our suffering. The Buddha’s teachings emphasize that ignorance (avijjā) is the primary cause of this clinging. Without understanding the nature of impermanence and non-self, we remain trapped in a cycle of craving and aversion.

“And what is ignorance (avijjā)…? Not knowing about dukkha, not knowing about the origin of dukkha, not knowing about the cessation of dukkha, and not knowing about the path that leads to the cessation of dukkha — this is called ignorance.”

— MN 9

The recognition of dukkha is not meant to instill pessimism but to foster a profound understanding of reality. By acknowledging suffering, one begins the journey toward its transcendence.

The Second Noble Truth: Samudaya - The origin of suffering

“And this is the noble truth of the origin of suffering: it is craving (tanhā) that leads to renewed existence (bhāva), accompanied by delight and lust, seeking delight here and there; that is, craving for sensual pleasures, craving for existence, and craving for non-existence.”

— SN 56.11

The second noble truth identifies tanhā (craving) as the root cause of suffering. This craving manifests in various forms:

- Craving for sensory pleasures (kāma-tanhā): The desire for pleasurable experiences, material possessions, and sensory gratification.

- Craving for existence (bhava-tanhā): The attachment to identity, personal achievements, and continued existence.

- Craving for non-existence (vibhava-tanhā): The desire to escape pain, suffering, or existence altogether.

Buddhism asserts that craving arises due to ignorance (avijjā) of the true nature of reality. The illusion of permanence and selfhood fosters attachment, leading to suffering. Craving perpetuates samsāra, binding beings to the cycle of rebirth and dissatisfaction. The second noble truth thus provides an essential link to paṭicca-samuppāda (dependent origination), demonstrating how ignorance and craving sustain suffering.

The Third Noble Truth: Nirodha - The cessation of suffering

“Through the cessation (nirodha) of the causes, suffering ceases: the complete fading away and ending, the giving up, relinquishing, and letting go of that very craving (tanhā).”

— SN 56.11

The third noble truth proclaims that the cessation of suffering (nirodha) is attainable. This cessation is not merely the absence of suffering but the complete extinguishing of craving and ignorance, leading to nirvāṇa. Nirvāṇa is described as the ultimate liberation, a state free from attachment, aversion, and delusion.

Buddhist texts distinguish between two forms of nirvāṇa:

- Nirvāṇa with remainder (saupādisesa-nirvāṇa): This occurs while an enlightened being is still alive, having extinguished craving but continuing to exist in a conditioned body.

- Final nirvāṇa (anupādisesa-nirvāṇa): This is attained at death when all remnants of conditioned existence are relinquished.

Nirvāṇa is not a place or state of eternal bliss but the realization of unconditioned reality. It transcends concepts of existence and non-existence, offering the cessation of suffering through the eradication of ignorance.

The Fourth Noble Truth: Magga - The path to the cessation of suffering

“And this is the noble truth of the path of practice leading to the cessation of suffering: precisely this Noble Eightfold Path — right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration.”

— SN 56.11

The fourth noble truth outlines the Noble Eightfold Path, the practical means by which suffering is overcome. This path is structured into three core disciplines:

- Wisdom (paññā)

- Right View (sammā-diṭṭhi): Understanding the Four Noble Truths and the nature of impermanence, suffering, and non-self.

- Right Intention (sammā-saṅkappa): Cultivating intentions of renunciation, goodwill, and harmlessness.

- Ethical conduct (sīla)

- Right Speech (sammā-vācā): Speaking truthfully, kindly, and avoiding harmful words.

- Right Action (sammā-kammanta): Engaging in ethical behavior by abstaining from killing, stealing, and harmful conduct.

- Right Livelihood (sammā-ājīva): Earning a living in a way that aligns with ethical principles and does not cause harm.

- Mental discipline (samādhi)

- Right Effort (sammā-vāyāma): Cultivating wholesome mental states while abandoning unwholesome ones.

- Right Mindfulness (sammā-sati): Developing present-moment awareness through meditation and mindfulness.

- Right Concentration (sammā-samādhi): Attaining meditative absorption (jhāna) that fosters deep insight and liberation.

The Eightfold Path is not a sequential process but an integrated practice where progress in one area strengthens the others. It offers a holistic approach to personal transformation, emphasizing both ethical behavior and profound meditative insight.

Conclusion

The Four Noble Truths stand as the most condensed and essential articulation of the Buddha’s philosophical insight. They not only provide a framework for understanding suffering, but also outline the existential structure of conditioned existence and the transformative path out of it. Each of the truths builds on the other: from diagnosing the ubiquity of suffering (dukkha), to identifying its cause (tanhā), revealing its cessation (nirodha), and finally presenting a method (magga) for attaining that cessation through ethical and meditative practice.

What makes this teaching so distinctive, especially when compared with Western philosophical and religious traditions, is its radical empiricism. The Four Noble Truths are not offered as metaphysical dogmas or theological commandments, but as existential insights to be verified through personal experience. While Western thought often oscillates between abstract rationalism and moral prescription, the Buddha’s method blends introspective analysis with ethical living and disciplined mindfulness. This results in a holistic approach to transformation that does not rely on divine authority, but on the direct observation of reality.

Moreover, the Buddhist approach avoids essentialist notions of a fixed self or permanent soul. It addresses human suffering not by promising external salvation or moral reward, but by unmasking the illusions that bind us to dissatisfaction. In doing so, it invites a form of liberation rooted in clarity, self-responsibility, and deep compassion.

While the Four Noble Truths are only the entry point into the Buddha’s broader teaching, they encapsulate its heart. Their continued relevance lies in their simplicity, their universality, and their invitation to practice rather than mere belief. They remain one of humanity’s most profound and practical answers to the question of how to live with — and ultimately transcend — suffering.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Klaus Mylius, Die vier edlen Wahrheiten - Texte des ursprünglichen Buddhismus, 1998, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150034200

comments