Anatta: The illusion of self

The Buddhist doctrine of non-self (anatta in Pāli, anātman in Sanskrit) is one of the most radical and fascinating concepts in Buddhist philosophy. It undermines the idea of a permanent, independent self, which is prevalent in many religious and philosophical traditions. In this post, we go beyond what we have already explored in our post on the Three Marks of Existence and deepen our understanding of the anatta doctrine through an in-depth examination of how the Buddhist notion of non-self challenges the idea of a fixed identity — through classical analogies, conceptual analysis, and its connection to the doctrines of emptiness (shunyata) and dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda).

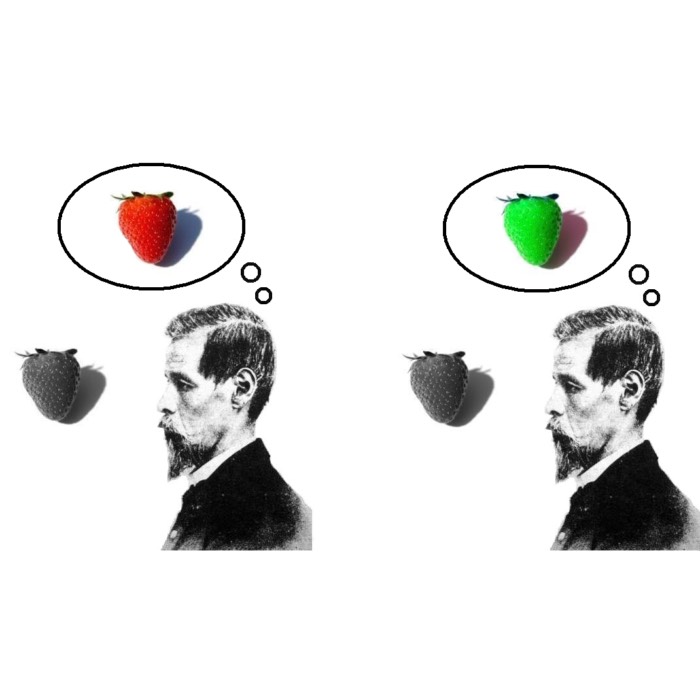

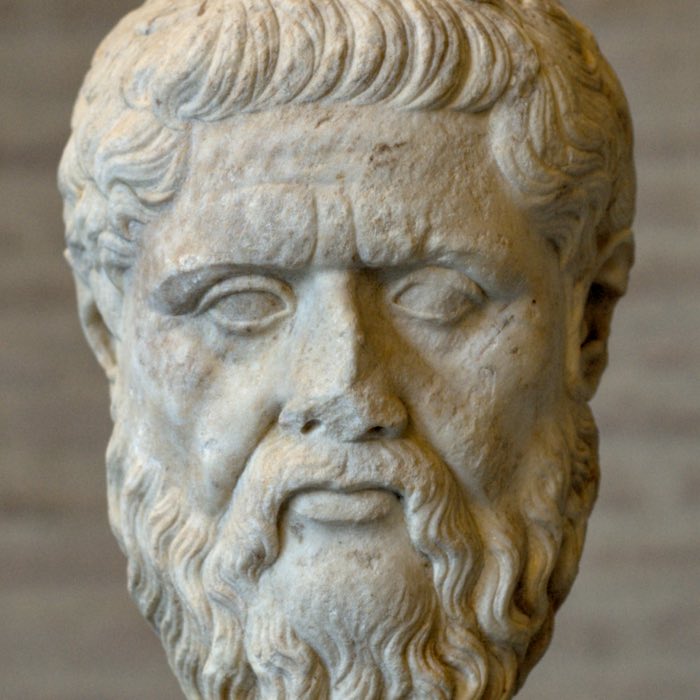

Illustration of a chariot, referencing the famous simile from the Milindapañha. According to the Buddhist monk Nāgasena, just as a chariot is merely the sum of its parts — wheels, axle, yoke — and not a substance of its own, so too is the self a conventional designation for the five aggregates (skandhas). No enduring essence can be found in either. Interpreted and generated by DALL•E.

The chariot analogy

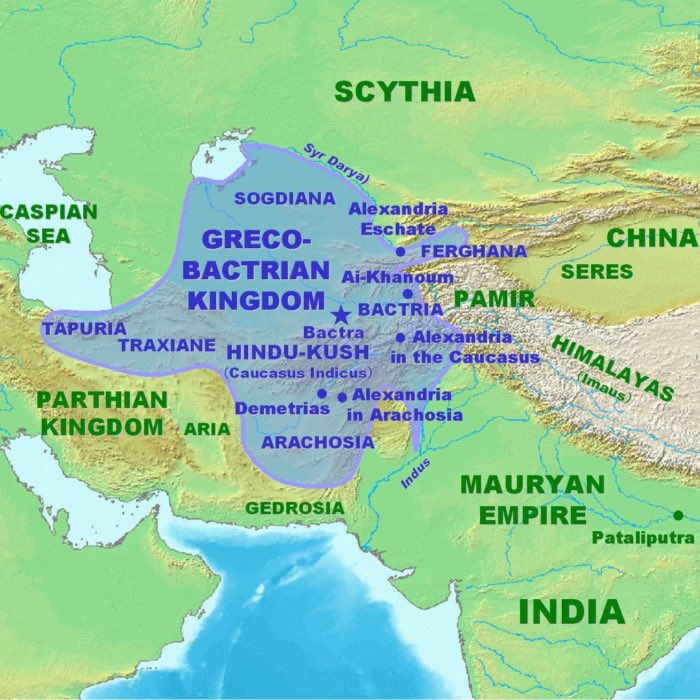

A famous analogy often used to illustrate the doctrine of non-self comes from a dialogue between the Buddhist monk Nāgasena and the Indo-Greek King Milinda. These Indo-Greek rulers were descendants of Alexander the Great’s campaigns and established Hellenistic kingdoms in parts of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India, blending Greek and local cultures in unique and historically significant ways.

When Milinda asked the Buddhist monk Nāgasena for his name, Nāgasena replied that “Nāgasena” was merely a convention, a way of speaking — because no independent person could be found. He compared himself to a chariot: neither the axle, nor the wheels, nor the yoke alone is the chariot. Only the sum of the parts gives rise to the conventional designation “chariot.” The same applies to a person: hair, skin, bones, sensations, perceptions, thoughts, and consciousness together form what we call a “human being.” But beyond these conditions, no self can be found.

“Just as when the parts are assembled

We speak of a chariot,

So too, when the aggregates are present,

We use the conventional term ‘person.’”

— SN 5.10

This insight points to the fact that both “person” and “self” are merely concepts generated by the mind. We perceive something and assign it a name — like “human” — yet that name refers only to a constructed idea that does not exist independently in reality. If we analyze this concept, we find parts such as an “arm”; the arm itself can be divided into “skin” and “muscles,” and so on. What we treat as a single entity dissolves into smaller parts, which in turn reveal no underlying essence. Our mind projects stability and coherence onto what is, in truth, a bundle of fleeting and conditioned phenomena. The supposedly substantial dissolves under close inspection, revealing itself as an illusion born of ignorance about the nature of reality.

Anatta as process ontology

What we call the “self” is not a thing or essence, but a process — a dynamic configuration of momentary events. This is the heart of the Buddhist process ontology: reality is not made up of stable substances but of fluctuating events. Every aspect of what we conventionally call a person consists of constantly shifting physical and mental components. These arise in dependence upon conditions and cease when those conditions fall away.

This view stands in stark contrast to substantive thinking, which often assumes that behind the flux of experience there is a stable essence or substance. Many Western metaphysical systems, for instance, posit a permanent, underlying substance or soul that persists through time — a stable core that we identify as the “self”. But Buddhism challenges this assumption by rejecting the idea of a permanent, unchanging substance beneath the surface. Instead, it teaches that what we conventionally call a “person” is merely a label for a continually changing pattern — a bundle of interconnected phenomena, arising and passing away in a flow.

This becomes particularly clear in the Buddhist analysis of the self through the five skandhas (Pāli: khandhas), or aggregates. These are the core components that, according to Buddhist thought, together form what we conventionally call a “person”. They are not separate entities but interdependent processes that arise and pass away in each moment. The five aggregates are:

- Form (rūpa) — the physical body and material phenomena

- Sensation (vedanā) — the feeling tone of experiences (pleasant, unpleasant, neutral)

- Perception (saññā) — the capacity to recognize and label what we encounter

- Mental formations (saṅkhāra) — volitions, intentions, emotional patterns, and habits

- Consciousness (viññāṇa) — the awareness that arises from sense contact

These aggregates do not operate independently but interdependently, forming a dynamic, ever-changing bundle of phenomena. Each moment of what we call “personal experience” is a particular configuration of these five. Crucially, none of them — either alone or in combination — constitutes a self. Siddhartha Gautama famously stated:

“Whatever there is of bodily form, feeling, perception, mental formations, or consciousness, whether past, present, or future, internal or external, gross or subtle, inferior or superior, far or near — one should rightly see: ‘This is not mine, this am I not, this is not my self.’”

— SN 22.49

If what I call “myself” is just a temporary arrangement of the Five Aggregates, then the “I” of this moment is never quite the same as the “I” of the next. Each configuration is fleeting, yet we habitually project continuity onto this sequence — much like we imagine a continuous film where in reality there are just frames. This illusion of personal continuity is reinforced by language and psychological inertia, making the self appear more stable than it truly is.

Just as we divide time into “today” and “tomorrow” along arbitrary lines (e.g., midnight), we also carve out the boundaries of the self in a similarly conventional yet ultimately illusory way. The term “I” refers to a flowing process of dependent phenomena — not to a metaphysical substance. On the ultimate level, there is no firm referent for the self.

This challenge to substantive thinking — the desire to find a permanent essence behind the process — is profound. In Buddhism, what we conventionally call a “person” is simply a name for a pattern of interdependent events, helpful in daily life but ultimately ontologically empty. The self is not a fixed substance, but a recognizable pattern, like a whirlpool or vortex — an identifiable arrangement of shifting elements. Later Buddhist thought would describe such patterns in terms of dhammas — irreducible experiential events, not atoms or substances. These dhammas swirl together into trees, mugs, or persons, yet no permanent substance stands behind them. Even the “person” is nothing but such a swirl, held together by craving (tanhā) and ignorance (avijjā).

Understanding this vision of selfhood is not a matter of abstract theory. It is a practice-oriented insight with liberating potential. When we let go of the fiction of a self that owns or controls experience, we begin to encounter life with greater clarity and lightness. In recognizing that we are processes rather than essences, we open the door to a freedom that no fixed identity could ever provide.

Personal identity, continuity, and the illusion of a stable self

If there is no stable self, what explains our sense of continuity — the feeling that we are the same person today as we were yesterday? From a Buddhist point of view, this continuity is real, but not substantial. It arises from an unbroken chain of causally connected physical and mental processes. Just as a flame appears continuous though it constantly consumes new fuel, so does the sense of identity arise from a seamless stream of impermanent phenomena.

Western philosophers like René Descartes famously sought the foundation of personal identity in a thinking substance — a rational soul or mind that persists through time. “I think, therefore I am”, he asserted. But for Siddhartha, this metaphysical claim is not only unnecessary, it is misleading. We do not need a hidden entity behind thoughts and sensations to explain them; they explain themselves through causality. As with fire: we do not assume an invisible fire-substance behind each flame — we see each flame arise from its specific conditions. Similarly, we need not posit an inner self behind the flow of experience.

From this insight follows a radical shift: there is no metaphysical “I” who experiences thoughts and feelings; there are just thoughts and feelings. Instead of saying “I am sad”, we can say, “Sadness is happening”. This subtle shift is deeply liberating. It severs the identification with fleeting mental states and shows us that what we call “I” is merely a label for an unfolding event in time. This undermines the very foundation of clinging and craving — because there is no one to cling and nothing to cling to.

Identity, then, is not a fixed trait but a functional convention — a way of speaking about the coherence of a process. It helps organize our lives and responsibilities, but it should not be mistaken for an ultimate truth. Letting go of the idea of a stable self does not erase the narrative of our lives, but it frees us from having to defend or perfect it. It invites us to stop clinging to the idea of a self that owns experiences or controls the flow of life. When we see ourselves as processes rather than essences, we open the door to letting go, to detachment, and ultimately to freedom from suffering.

Craving, insecurity, and the engine of suffering

If the self is a process and not a substance, then it depends on favorable conditions to continue unfolding. Unlike a metaphysical soul, this self-process is fragile: it requires oxygen, food, warmth, recognition, and meaning to sustain itself. But these conditions are never fully within our control. They may change, be lost, or become inaccessible — and that renders the self-process fundamentally insecure.

This existential instability is the foundation of tanhā, or craving. Because the self is experienced as precarious, it clings: to comfort, to safety, to validation. What we call “wanting” is not just a desire for objects, but a structural necessity of the self-process to perpetuate itself. The illusion of self creates a thirst for permanence, satisfaction, and control — goals that reality continually frustrates.

Seen from this angle, suffering (dukkha) is not an unfortunate accident but the default condition of a being who falsely believes in a stable self. As long as we are caught in this illusion, there will always be something we lack, something we want, something we fear to lose. Siddhartha’s diagnosis is not moralistic but structural: craving exists because the illusion of self exists. The very belief in a permanent, independent self fosters the constant drive to satisfy and protect that self. In our delusion, we think we are acting in ways that fulfill this “self” — we seek external pleasures, achievements, and validations, believing that these will fix or sustain the self.

But no matter how much we gain, it is never enough. Even when we get what we want, it is temporary, fleeting, and ultimately unsatisfactory. The very structure of craving creates a never-ending cycle of wanting — there is always something else to desire, something else to fear losing. This cycle is what perpetuates dukkha. Our desire for permanence, rooted in the illusion of a stable “self”, is doomed to frustration because everything is impermanent. The craving to satisfy the self becomes an engine that drives endless dissatisfaction, reinforcing the delusion of a fixed identity while simultaneously deepening our suffering.

Freedom becomes possible only when this illusion is seen through. If there is no fixed self, there is also no one to defend, no permanent lack to fill, no final goal to reach. The relentless striving to protect or enhance a self, to perpetuate its narrative, or to acquire what it lacks is what keeps us bound in suffering. Once we recognize that there is no “self” to protect or to improve, that pursuit dissolves, leaving behind a profound sense of ease and openness.

The path of insight leads not to a perfected self, but to the realization that no such self was ever needed. Without the burden of clinging to a permanent “I”, the cycle of craving and suffering gradually unravels. We no longer need to chase fleeting desires to fill an illusory void, nor do we need to defend or justify our identity. What remains is a direct, unmediated experience of life as it is — fluid, interconnected, and ever-changing. This is not a passive resignation but an active freedom: the freedom to engage with the world without the distortions of ego, to act with compassion and clarity, and to let go of the need for control. In seeing the self as an illusion, we find a liberation that is not dependent on any fixed, permanent state, but on the continual unfolding of the present moment.

Conventional fictions and ultimate reality

None of this means that we must abandon everyday language or social functioning. Siddhartha did not deny the usefulness of conventional designations like “I,” “you,” or “today.” These labels are indispensable for practical purposes — from making appointments to taking moral responsibility. But they should not be mistaken for realities with independent existence.

Just as we divide time into “days” and “months” for convenience, we divide experience into “selves” and “others” to navigate the world. These divisions are not inherently real; they are conceptual boundaries we draw within a fluid and interconnected process. They are like lines drawn on water — briefly helpful, never ultimate.

The Buddhist path does not require us to stop saying “I”. It invites us to say it with wisdom — understanding that behind the word lies no unchanging essence, only a functional label for what is dependently arisen and constantly changing. To live this insight is not to erase the self, but to see through its illusion — and in doing so, become free from its burdens.

All dharmas are empty – impermanence and non-self beyond the person

The Buddhist insight into non-self (anatta) does not end with the deconstruction of the personal identity. It applies equally to all things — to every phenomenon (dharma) that appears in experience. In Buddhist philosophy, dharmas – not to be confused with dharma, usually used in singular and which refers to the universal truth or law of nature — are understood as the most basic constituents of reality — elementary events or processes that cannot be further broken down into parts. They are not particles or atoms, but momentary units of experience and causal function. The five skandhas are composed of such dharmas, but they do not exhaust them; reality consists – according to the Abhidharma tradition – of many other dharmas as well, such as attention, contact, intention, or effort. This understanding of dharmas leads us to a broader insight: just as there is no stable essence behind the idea of a “self,” so too there is no intrinsic substance behind a “tree,” a “table,” or a “thought”. All such entities are merely temporary configurations of conditions — dependent, composite, and subject to change.

This insight extends the principle of impermanence (anicca) to everything: not only is the self in flux, but so is the world we assume to be composed of discrete and enduring things. In reality, what we take to be “things” are just mental constructions — names given to constantly shifting relational patterns. Just as a person is composed of Five Aggregates, objects and concepts dissolve under analysis into smaller parts and interdependent processes.

Depiction of a jacket with a detached sleeve. The image illustrates how everyday objects — like a “jacket” — are mental constructs composed of parts. When analyzed, no essence can be found: the jacket dissolves into fabric, seams, buttons, and sleeves, each of which can be further deconstructed. Like the self in the doctrine of anatta, it exists only as a convenient designation. Interpreted and generated by DALL•E.

From this perspective, all dharmas are empty (shunyata) — not nonexistent, but devoid of inherent nature (svabhāva). This emptiness does not negate their appearance or practical function; it reveals that their being is conditioned and contingent. Just as “self” is a label for a process, so are “cup”, “sky”, or “emotion.” Every name we give to things is a convenient fiction that helps us orient ourselves in a world that, at its core, resists all attempts to freeze it into stable identities.

Consider the relativity of properties: whether a finger is “long” or “short” depends entirely on what you compare it to. Length is not an absolute characteristic but arises from relationships. In the same way, the existence and identity of any phenomenon depend on its context and conditions. This is pratītyasamutpāda — dependent origination — the principle that nothing exists in isolation. Everything arises in a web of causes, and everything changes when those causes change.

At the same time, every property — like every form — is impermanent. If conditions shift, so does the phenomenon. This is true of bodies and thoughts, jackets and muffins. Thus, not only the self but all dharmas are without fixed identity. All are impermanent, interdependent, and empty. To see this clearly is to see that clinging — whether to a self or to things — is always misplaced.

Conclusion

The doctrine of anatta — non-self — challenges one of the most deeply held assumptions in both common intuition and much of Western philosophical thought: that behind our experiences, there exists a stable, enduring subject — a “self” or “I” that thinks, acts, and persists through time. Buddhism dismantles this notion at every level. Through the chariot analogy, the analysis of the Five Aggregates, and the insight into dependent origination, it reveals that what we call a “person” is merely a convenient label for a constantly changing process. There is no hidden core, no metaphysical substance behind our thoughts, feelings, and actions. Instead, we find a dynamic stream of conditioned events — physical, emotional, and cognitive — without any unchanging essence.

This view is not an abstract metaphysical claim, but a pragmatic and liberating insight. It removes the burden of having to defend, define, or perfect a fixed identity. It shows that the self is neither sovereign nor stable — and this very fragility, when misunderstood, gives rise to craving, fear, and suffering. By seeing through the illusion of self, one is no longer caught in its endless drama. This is not nihilism, but freedom: the freedom to participate in life without clinging, to experience without ownership, to act without being chained to a narrative of “me” and “mine”.

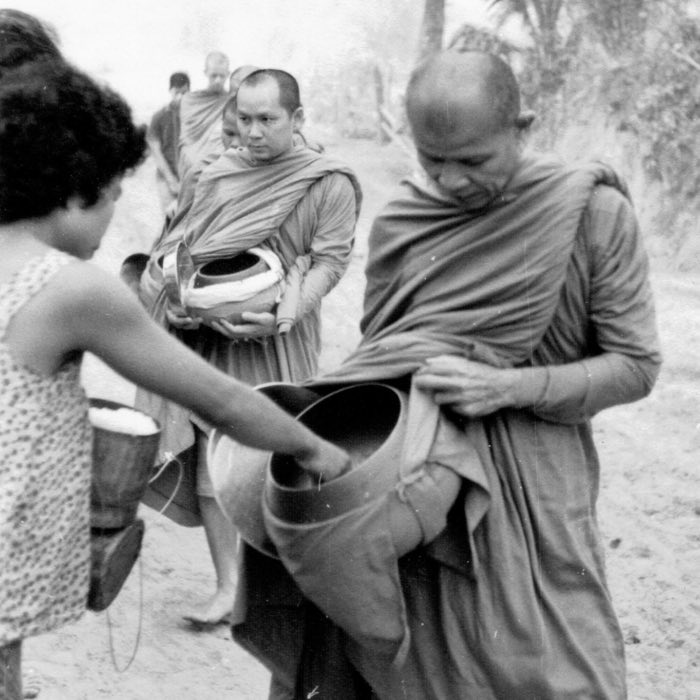

Compared to Western philosophies of identity — especially those rooted in the soul-substance of Plato, the rational ego of Descartes, or even the transcendental subject of Kant — the Buddhist view stands out for its radical refusal to posit any metaphysical anchor behind experience. Where Western traditions often seek to locate the self (in reason, memory, continuity, or will), Buddhism dismantles the very question. It asks not “what am I?” but “why do I think there must be an ‘I’ at all?” In this way, Buddhist thought avoids the circular traps of self-reference and the existential burdens that come with them.

This perspective highlights Buddhism’s unique approach to addressing the lived reality of suffering and the existential anxiety tied to self-clinging. While Western models often frame suffering as a challenge for the self, Buddhism reframes it as arising from the self. By revealing the self as a construct, it provides not only insight but also a path toward transformation.

Of course, the Buddhist denial of self does not imply that nothing exists or that personal responsibility is meaningless. Rather, it reframes existence as process and responsibility as participation. It allows for ethics, story, and growth — but without the metaphysical weight of ego. The “self” becomes a useful fiction, not a prison.

To fully grasp anatta is not merely to understand a concept, but to see through the illusion that sustains suffering. In the end, what the Buddhist tradition offers is not a new answer to the question “Who am I?” — but the wisdom to stop asking it in the old way.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments