Tanhā: The root of craving and the cycle of suffering

Among the fundamental insights of Buddhist philosophy, tanhā stands as one of the most pivotal and far-reaching. Commonly translated as “craving” or “thirst”, tanhā is identified by Siddhartha Gautama as the primary cause of suffering (dukkha) and the driving force behind saṁsāra, the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. More than just a desire for pleasure, tanhā encapsulates the human tendency to cling to experiences, resist change, and perpetuate patterns of attachment and dissatisfaction. Understanding tanhā, its manifestations, and its role in perpetuating suffering is crucial for anyone seeking liberation within the framework of Buddhist thought. In this post, we take a look at the nature of tanhā, its psychological and existential dimensions, and the path to overcoming this fundamental obstacle to awakening.

Demonic figure with a flaming head from the Japanese emakimono Kako genzai e-inga-kyō (The Illustrated Sutra of Past and Present Karma), 13th century (Kamakura period). Scene from the temptations and meditative trials of the ](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-05-18-siddhartha_gautama/). This narrative handscroll illustrates karmic causality through visual allegory. The exaggerated features of the figure shown in this excerpt — bulging eyes, sharp teeth, clawed limbs — and especially the fiery crown, mark it as an embodiment of dangerous inner forces. Its grotesque, animated posture suggests aggression and disruption, typical of depictions of Māra’s army attempting to obstruct the Buddha’s path to awakening. The flaming motif is deeply symbolic in Buddhist thought, especially in the context of taṇhā (Pāli; Sanskrit: tṛṣṇā), or “craving” — a central cause of suffering in the Four Noble Truths. The fire symbolizes desire’s consuming nature, as expressed in sutras like the Ādittapariyāya Sutra (“Fire Sermon”), which describes the senses and consciousness as “burning” with the flames of greed, hatred, and delusion (the Three Poisons). Here, craving is personified: not as an abstract principle but as a demonic agent, wild and ravenous. Its visual kinship to beings from other Buddhist traditions — such as Tibetan flame-wreathed demons or the pretas of Theravāda cosmology — underscores the universality of this iconography. Yet the Japanese emakimono style adds a distinctive liveliness and grotesque humor, which sharpens the didactic impact. This demon, therefore, is more than a mythical creature: it is a visual metaphor for the destabilizing force of taṇhā, ever ready to seize the mind and bind it to saṃsāra. Source: Met Museumꜛ (license: public domain)

The nature of tanhā

The term tanhā originates from the Pāli and Sanskrit root “tṛṣ”, meaning “to thirst”. This metaphor of thirst aptly conveys the restlessness and insatiable quality of craving — an unrelenting drive that binds beings to the world of conditioned existence. In Buddhist philosophy, tanhā is not merely a superficial longing for external pleasures; it is a deep-seated psychological force that shapes perception, intention, and action. It is at the core of why beings remain ensnared in saṁsāra, generating karma (volitional actions) that lead to continued rebirth and suffering.

The ](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-05-18-siddhartha_gautama/) categorizes tanhā into three main forms:

- Kāma-tanhā (craving for sensual pleasure) – This refers to the attachment to sensory experiences, including material wealth, physical pleasures, aesthetic beauty, and emotional gratification. It is the craving that arises from the five senses — sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch — drawing beings toward transient sources of pleasure that ultimately fail to provide lasting fulfillment.

- Bhava-tanhā (craving for becoming) – This is the craving for existence, identity, and continuity. It manifests in the desire to establish and reinforce the self, whether through status, achievements, ideologies, or spiritual attainments. Bhava-tanhā fuels the illusion of a stable, enduring self (atman), binding beings to a sense of personal continuity and reinforcing their investment in an impermanent world.

- Vibhava-tanhā (craving for non-existence) – The counterpart to bhava-tanhā, this form of craving arises from aversion rather than attachment. It is the desire for annihilation, oblivion, or escape from suffering through self-destruction or extreme forms of asceticism. Rather than addressing the root of suffering, vibhava-tanhā seeks to negate existence without true liberation, often leading to further suffering.

Tanhā and the second noble truth

The Buddha’s teaching of the Four Noble Truths places tanhā at the center of the human predicament. While the first noble truth (dukkha) establishes that suffering is an inherent feature of conditioned existence, the second noble truth (samudaya) explains that suffering arises from craving. This is a crucial departure from other Indian philosophical traditions that may attribute suffering to fate, divine will, or cosmic imbalance. Instead, the Buddha’s diagnosis is psychological and existential: Suffering originates in the mind’s tendency to grasp, cling, and resist the nature of reality.

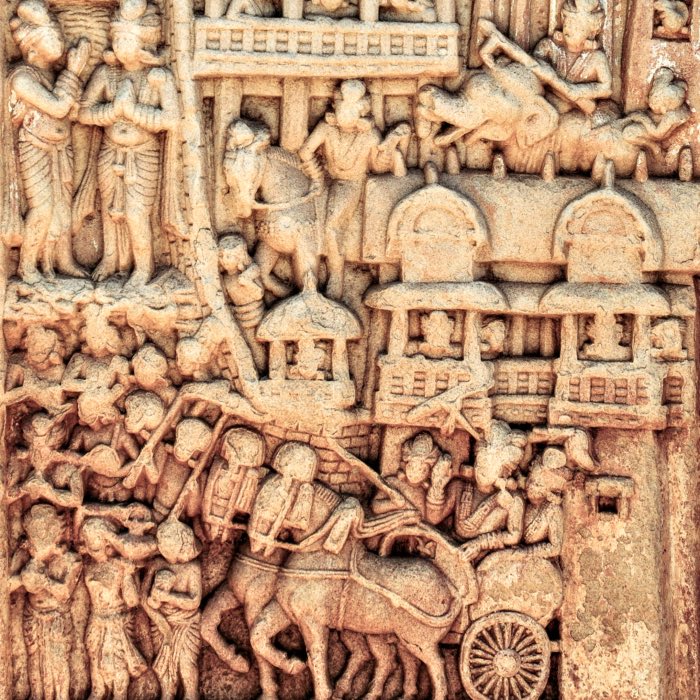

The mechanism by which tanhā perpetuates suffering is further elaborated in the doctrine of paṭicca-samuppāda (dependent origination), which describes the twelve interconnected links that sustain saṁsāra. Tanhā arises as a direct result of sensory contact (phassa) and leads to clinging (upādāna), which then conditions becoming (bhava), resulting in rebirth (jāti) and the continuation of suffering (jarāmaraṇa — aging and death). This cyclical process illustrates how craving serves as a reinforcing mechanism, propelling beings through the endless cycle of birth and death.

Psychological and existential dimensions of tanhā

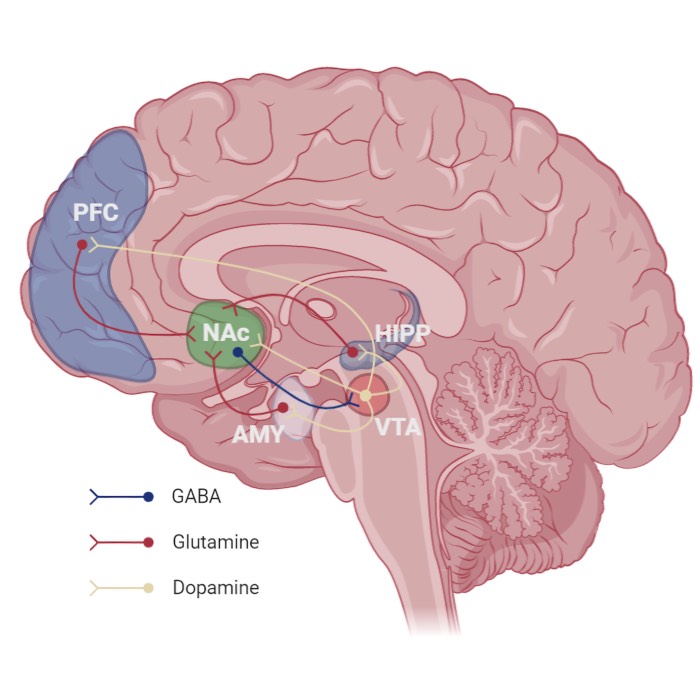

From a psychological perspective, tanhā can be understood as the underlying force behind attachment patterns, compulsions, and dissatisfaction. It is closely tied to the Three Poisons (akusala-mūla) — greed (lobha), hatred (dosa), and delusion (moha) — which distort perception and reinforce self-centered tendencies. Modern psychology echoes these insights, particularly in the study of hedonic adaptationꜛ and attachment theory, which describe how individuals seek pleasure yet quickly become desensitized to it, resulting in a cycle of craving and temporary satisfaction.

Existentially, tanhā is linked to the illusion of selfhood. The attachment to an enduring “I” leads to fear of loss, striving for permanence, and aversion to change. By recognizing tanhā as a conditioned response rather than an intrinsic essence, one begins to loosen the grip of self-identification and cultivate a more liberated mode of being.

Overcoming tanhā: The Path to Liberation

Buddhism does not advocate for repression or forceful renunciation of tanhā but rather for its understanding and transcendence through wisdom (prajñā), ethical conduct (sīla), and meditative cultivation (samādhi). The Noble Eightfold Path provides the structured means by which craving can be weakened and ultimately extinguished:

- Right view and right intention correct misperceptions about the self and reality, allowing one to see tanhā as a conditioned phenomenon rather than an inherent necessity.

- Right speech, right action, and right livelihood encourage ethical discipline that reduces attachments to material and social desires.

- Right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration cultivate the mental clarity necessary to observe craving without succumbing to it, fostering equanimity and insight.

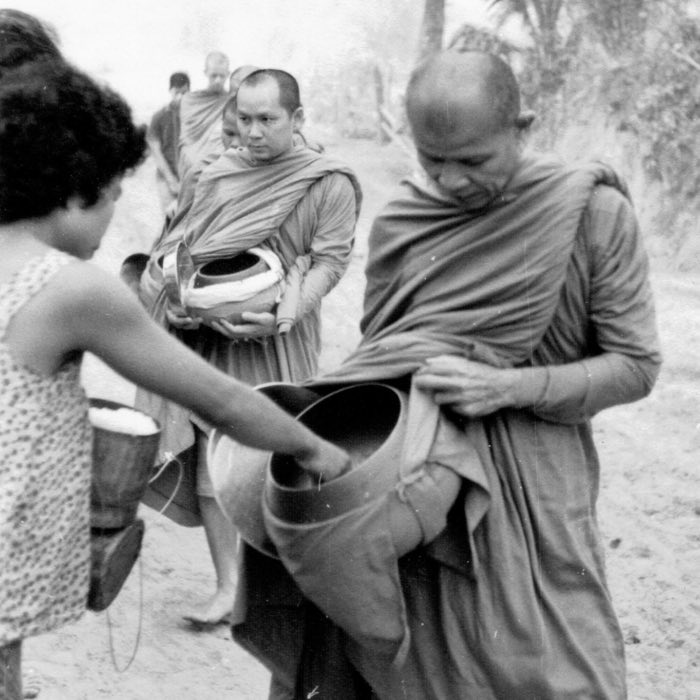

Meditative practices such as Vipassanā (insight meditation) are intended to allow individuals to observe tanhā in real-time, recognizing its arising and passing without attachment. According to Buddhist thought, this process gradually leads the mind to relinquish its habitual grasping, resulting in the cessation of suffering and the attainment of nirvāṇa, the state beyond craving and attachment.

Conclusion

Tanhā is not merely an abstract concept but a direct and pervasive force that shapes human experience. It operates as the engine of saṁsāra, driving the patterns of birth, death, and rebirth through clinging and aversion. Yet, within the teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, tanhā is not an insurmountable burden but a condition that can be understood, weakened, and ultimately overcome. Buddhist thought holds that through the cultivation of insight, ethical conduct, and meditative discipline, practitioners may gradually dismantle the fetters of craving and progress toward a state of true peace and liberation.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Wikipedia article on hedonic adaptationꜛ

- John Bowlby, Attachment and Loss: Volume I – Attachment, 1997, Pimlico, ISBN: 978-0712674713

comments