The Five Aggregates: Deconstructing the illusion of self in Buddhist thought

The concept of the Five Aggregates (pañcakkhandha in Pāli, pañcaskandha in Sanskrit, with khandha and skandha both meaning “aggregate” or “heap”) lies at the heart of Buddhist psychology and metaphysics. It serves as Siddhartha Gautama’s response to the age-old question of personal identity: What constitutes the self? Unlike many religious and philosophical traditions that posit a permanent, unchanging essence — often referred to as the soul or ātman in Indian thought — Buddhism presents a radically different view. The doctrine of anatta (Pāli) or anātman (Sanskrit) asserts that there is no fixed, independent self. Instead, what we conventionally call a “person” is merely a dynamic interplay of five psychophysical aggregates. In this post, we explore the Five Aggregates in detail, their role in sustaining the illusion of self, and their implications for achieving liberation (nirvāṇa) from suffering (dukkha).

Figure of a deity (oceanic art), Nukuoro, Caroline Islands, Micronesia, 19th century, wood, Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Cologne, Germany. In Buddhist thought, the person as conventionally perceived is not a substantial self (ātman), but rather a provisional designation based on the five skandha — form (rūpa), sensation (vedanā), perception (saṃjñā), mental formations (saṃskāra) and consciousness (vijñāna). Just as this wooden figure evokes the human form without representing an individual person, so too does the self in Buddhist thought emerge from the dynamic interplay of impermanent aggregates, empty of intrinsic essence yet functionally coherent.

The atman-anatta debate – The Buddhist rejection of a permanent self

One of the most significant philosophical debates in Indian thought revolves around the existence of an eternal, unchanging self (ātman). Vedic traditions, particularly those found in the Upanishads, posit that the true self (ātman) is identical to the ultimate reality (Brahman). This metaphysical self is believed to persist beyond death, undergoing cycles of rebirth until it attains liberation (moksha).

Buddhism challenges this notion with its doctrine of anatta. Siddhartha Gautama argued that clinging to the idea of an enduring self leads to attachment, craving (tanhā), and suffering (dukkha). He deconstructed the self by analyzing human experience into the Five Aggregates, showing that none of them — individually or collectively — constitutes a stable essence.

In the Anattalakkhana Sutta (SN 22.59), Siddhartha explicitly states that if the aggregates were truly “self”, they would be under one’s control and not subject to change (“This is not mine, this I am not, this is not my self.”). However, because they are impermanent and conditioned, they cannot be identified as “me” or “mine”. The illusion of a self arises when consciousness and mental formations mistakenly impute continuity and ownership to these transient processes.

The Five Aggregates: A breakdown of experience

The Five Aggregates serve as a framework for understanding human experience, categorizing the elements that give rise to consciousness and the illusion of a personal identity. Each aggregate (Pāli: khandha; Snaskrit: skandha) represents a fundamental aspect of existence, none of which can be identified as a permanent self:

- Form (rūpa): the physical body and material phenomena

- Feeling (vedanā): sensations arising from contact with the external world

- Perception (saññā): the cognitive process of recognizing and labeling experiences

- Mental formations (saṅkhāra): volitional mental activities, including intentions and emotions

- Consciousness (viññāṇa): the awareness of sensory experiences

These aggregates are not separate entities but interdependent processes that arise and cease in a continuous flow. They are conditioned by one another and by external factors, illustrating the Buddhist principle of paṭicca-samuppāda (dependent origination). This means that the aggregates are not fixed or permanent; they are constantly changing and evolving based on their interactions with the world.

The Five Aggregates can be divided into two domains:

- Rūpa: physical form

- Nāma: mental factors — vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, viññāṇa

Together they make up nāma-rūpa, “name-and-form”. Only rūpa can be physically grasped, while the others exist as processes that can only be identified or “named”.

1. Form (rūpa): The physical basis of experience

The first aggregate, rūpa (Pāli/Sanskrit), refers to the physical body and material phenomena. It includes the sense organs — eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind — as well as the corresponding external objects of perception. Rūpa is subject to impermanence (anicca); it ages, deteriorates, and eventually ceases, highlighting its inability to provide a stable foundation for identity.

In Buddhist analysis, sensory perception arises through six primary faculties, each linked to a specific category of sensory objects:

| Sense organ | Function | Objects of perception |

|---|---|---|

| Eye | Seeing | Forms, colors, everything visible |

| Ear | Hearing | Sounds, tones, everything audible |

| Nose | Smelling | Scents, fragrances, everything olfactory |

| Tongue | Tasting | Flavors, everything taste-related |

| Body | Touching | Pressure, solidity, moisture, temperature, air movement |

| Mind | Thinking | Thoughts, ideas, mental constructs |

This classification highlights how the body acts as the interface between consciousness and external reality. However, the perception of form is fleeting; it is dependent on conditions and thus lacks inherent self-existence. Since our sensory experiences constantly change, clinging to them as a source of identity leads to suffering (dukkha).

Form is the first contact point (phassa) between the mind and the external world. It is through rūpa that we experience the world, but it is also the most deceptive aggregate, as it can create a false sense of permanence and solidity. The body, while tangible, is ultimately impermanent and subject to decay. Recognizing this impermanence is crucial for understanding the nature of existence and our relationship with the world.

2. Feeling (vedanā): The qualitative aspect of experience

Vedanā encompasses sensations that arise from contact (phassa) between the sense organs and external stimuli. These feelings are categorized into three types:

- Pleasant (sukha-vedanā)

- Unpleasant (dukkha-vedanā)

- Neutral (adukkhamasukha-vedanā)

Thus, every experience is accompanied by a qualitative tone — pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral — that shapes our reactions and decisions. These feelings, while fleeting, often become the basis (“seeds”) for attachment (upādāna) or aversion (dosa), fueling the cycle of craving (tanhā) and suffering (dukkha). Recognizing the impermanence of these sensations is a key step in breaking free from the illusion of a stable self and the grip of conditioned existence.

3. Perception (saññā): Recognizing and labeling experience

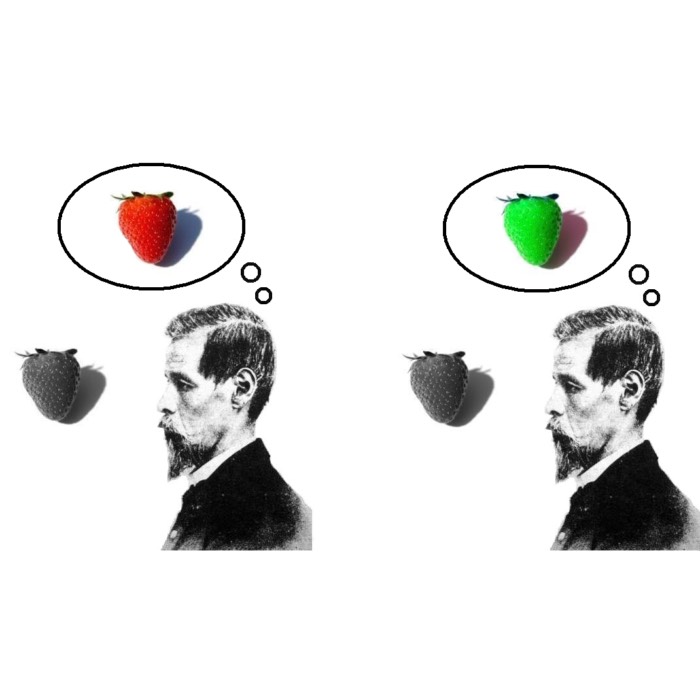

Saṇñā refers to the cognitive process of recognizing, identifying, and labeling sensory input. When we see an object, for instance, saṇñā helps us distinguish it as a “tree” or a “person.” This aggregate plays a crucial role in conceptualizing the world and forming memory. However, perceptions are conditioned by past experiences and cultural constructs, making them inherently subjective and impermanent.

4. Mental formations (saṅkhāra): The constructive aspect of experience

The fourth aggregate, saṅkhāra, refers to volitional mental formations, including intentions, desires, emotions, habits, and karmic dispositions. These formations shape behavior and reinforce patterns of thought and action. Since saṅkhāra is conditioned by past experiences and actively conditions future ones, it plays a crucial role in the cycle of samsāra. Importantly, the illusion of an autonomous self arises from deeply ingrained mental formations that create a sense of continuity and identity.

5. Consciousness (viññāṇa): The awareness of experience

The final aggregate, viññāṇa, denotes the faculty of awareness. It arises in dependence on the other aggregates and is categorized based on the six sense faculties: visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile, and mental consciousness. Viññāṇa is not a self-sustaining entity but a conditioned process that ceases when its causes and conditions cease. Siddhartha likened consciousness to a flame dependent on fuel — without fuel, it extinguishes.

Example of the interplay of the aggregates

To illustrate how the illusion of self arises from the interaction of the aggregates, consider a familiar moment:

You’re walking through a park on your break and hear the soft melody of a street musician playing nearby:

- Your ears pick up the sound, and your eyes register the movement of the performer’s hands — this is form (rūpa), the physical basis of your sensory contact (phassa).

- The tune feels soothing and uplifting — this is feeling (vedanā), the pleasant quality accompanying the experience.

- You recognize the melody and think, “Ah, that’s one of my favorite songs” — this is perception (saññā), the act of labeling and interpreting the stimulus.

- You decide to slow down and enjoy the moment, perhaps even smile or nod in appreciation — this is mental formation (saṅkhāra), the volitional and emotional response forming intention.

- All of this unfolds in the field of consciousness (viññāṇa), which integrates the various impressions into a coherent experience.

From this interplay arises the thought: “I’m enjoying this music.” But the “I” in that thought is simply a mental label for a momentary configuration of aggregates. As you continue walking, the music fades, your attention shifts, and a different set of aggregates comes into play — yet the sense of a persistent “self” lingers. In truth, the music-enjoying self has already dissolved.

Visualizing the interplay of the aggregates

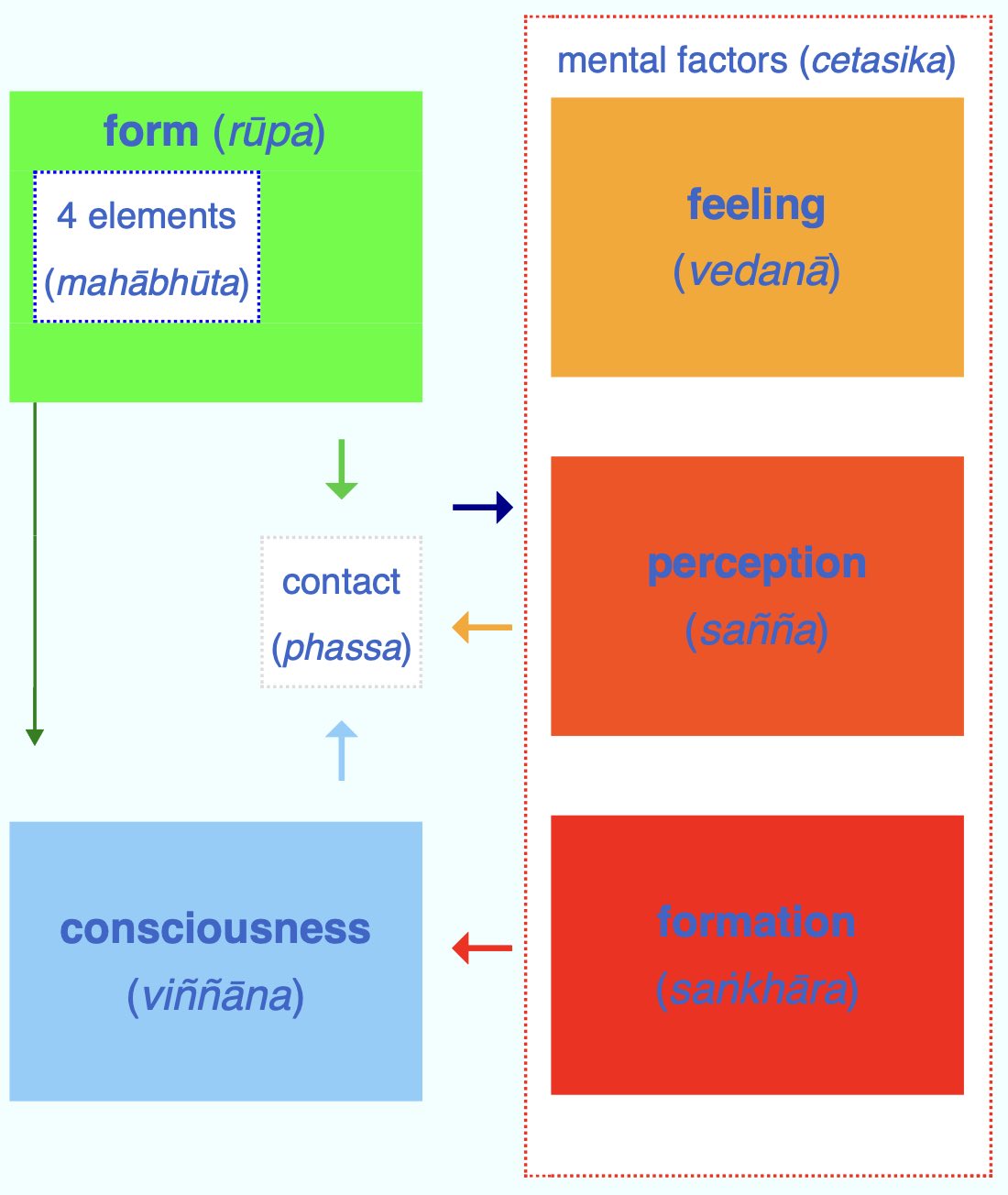

The Wikipedia articleꜛ on the Five Skandhas contains a well-designed diagram illustrating how the Five Aggregates dynamically interact to create a single moment of experience. Based on canonical descriptions such as Majjhima Nikāya 109 (Mahāpuṇŋama Sutta), it adds conceptual clarity to the nature of Buddhist psychology:

The interplay of the Five Aggregates (pañca khandha) according to the Pali Canon. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)ꜛ.

The interplay of the Five Aggregates (pañca khandha) according to the Pali Canon. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)ꜛ.

The five core aggregates are represented here as follows:

- Form (rūpa): The physical basis of experience, built upon the four great elements (mahābhūta): earth (solidity), water (cohesion), fire (temperature), and air (movement). According to early Buddhist cosmology, these four elements are not only the foundational constituents of the body, but of all material phenomena in the world. Everything physical, including the natural environment and objects of perception, is seen as composed of various proportions of these elements. They are not particles or substances in the modern sense, but qualities or forces that underlie all material form. This elemental model provides the conceptual foundation for understanding rūpa — both within the individual and in the broader field of experiential reality.

- Feeling (vedanā), Perception (saññā), and Formation (saṅkhāra): These are grouped together as mental factors (cetasika) and arise in tandem during each conscious event. In Abhidhamma literature, cetasikas are detailed as mental factors that arise alongside consciousness (citta) to shape the quality and function of a moment of experience. While some cetasikas are ethically neutral or universal (such as attention or contact), others are wholesome or unwholesome, depending on the ethical character of the mind state they accompany. In this context, vedanā, saññā, and saṅkhāra are understood as core cetasikas that contribute to how consciousness interprets and reacts to what is experienced.

- Consciousness (viññāṇa): Awareness that arises dependent on a particular sense modality and its corresponding object.

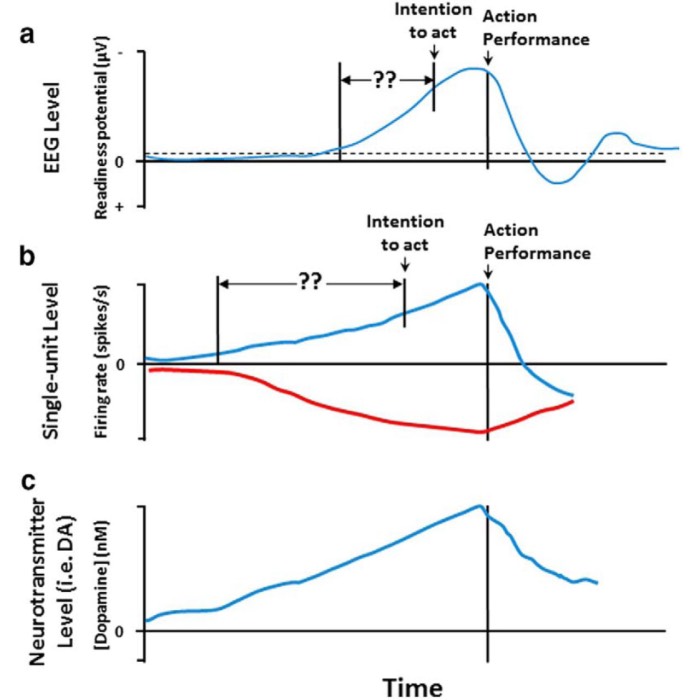

Contact (phassa) is a key event within the diagram. It occurs at the moment when a sense object (rūpa), a corresponding sense organ, and consciousness converge. In the canonical model, phassa is the trigger for the arising of further mental factors — especially vedanā (feeling), saññā (perception), and saṅkhāra (formation). While contact itself is ethically neutral, it sets the stage for how the mind reacts to experience, often leading to craving, clinging, or aversion if mindfulness is absent. It is precisely at this junction — where raw sensory contact transforms into psychological reactivity — that the illusion of a self often begins to take shape.

The diagram illustrates these relationships through directional arrows, each representing a specific causal sequence:

- ↓ The left-most green arrow from form to consciousness represents how form (such as a sound) gives rise to form-specific consciousness (such as auditory-consciousness).

- ↓ The right-most lime-green arrow from form to contact in tandem with the light-sky-blue arrow (↑) from consciousness represents how these two aggregates touch to create or touch through contact.

- → The dark-blue arrow from contact to mental factors represents that contact gives rise to feeling, perception and formation.

- ← The orange arrow from mental factors to contact in tandem with the light-sky-blue arrow (↑) from consciousness represents how these two aggregates touch to create or touch through contact.

- ← The red arrow from mental factors represents how mental factors (such as a perception) give rise to consciousness.

An example of a temporally ordered sequence of phenomena could be:

- The arising of form gives rise to consciousness.

- Form and consciousness make contact (phassa). (in other words: consciousness accesses form through contact)

- Contact gives rise to the mental factors (cetasika).

- Mental factors in turn give rise to new consciousness.

- Consciousness and mental factors, through contact, then give rise to further mental factors …

The directional arrows thus reflect a dynamic, looping process. At each moment, contact (phassa) arises from the convergence of form and consciousness, giving rise to the mental factors — feeling, perception, and formation. These mental factors shape and condition the arising of a new moment of consciousness, which in turn re-engages with form, producing fresh contact. In this way, the entire process moves in a circular fashion, each component influencing and giving rise to the next. Because this cycle operates continuously and seamlessly, it creates the impression of an ongoing, coherent “self” — but in reality, what appears as a stable identity is merely the product of this unbroken causal chain. None of the elements involved are permanent or self-existing; they are all conditioned, impermanent, and in constant flux. The self, then, is not found within this system, but is a conceptual overlay imposed upon its transient configurations.

In short, the illusion of self arises not because the self is somewhere in this system, but because the mind misreads this conditioned process as if it were a unified subject behind the flow of experience.

This misreading is deeply habitual and emotionally charged. It underlies craving (tanhā), attachment (upādāna), and ultimately suffering (dukkha). By carefully observing this dynamic — as visualized here — and recognizing its impersonal, conditional nature, insight (vipassanā) can arise. This insight cuts through the illusion, revealing that what we call “self” is simply the label placed on an interdependent and ever-shifting stream of phenomena.

In the next section, we will further explore the implications of this understanding, particularly in relation to the ethical dimensions of Buddhist thought and practice.

The illusion of a self

The person as process, not substance

Although Buddhism denies the existence of an enduring self (ātman), it does not deny the conventional reality of a “person”, by some schools called the pudgala (Pāli/Sanskrit). The pudgala is a conventional designation for the experiential stream constituted by the Five Aggregates. It is important to note that this term does not imply a metaphysical self or an unchanging essence; rather, it refers to the functional unity of the aggregates as they manifest in daily life.

In day-to-day life and social interaction, the term “person” is used to refer to the continuity of psychophysical processes that arise through the interaction of the Five Aggregates. This is not a denial of experience, but a rejection of the claim — sometimes made by critics or misunderstood by casual readers — that Buddhism nihilistically denies the reality of persons altogether. What Buddhism actually denies is the existence of a permanent, independent substance behind the person. It is, therefore, not a denial of lived experience, but of ontological mislabeling. Siddhartha’s insight was that what we call “a person” is not a thing, but a process — a dynamic stream of events without fixed boundaries. This idea aligns with a broader process ontology, in which all that exists does so only insofar as it participates in events. Just as we draw an arbitrary line between “today” and “tomorrow,” so too do we designate an “I” amid the flowing aggregates. The boundaries of this “I” are not objectively real, but conceptually imposed.

Dependent co-arising and mutual influence

This pragmatic approach allows Buddhism to maintain ethical accountability and causal continuity (especially concerning karma and rebirth) while denying the existence of a metaphysical or independent self. The person, in this understanding, is not a fixed entity existing on its own terms, but a dynamic interplay of interdependent phenomena — a stream of processes that arise and cease in dependence on conditions. What we conventionally call a “person” is a name given to this ever-changing network of causes and effects. The continuity we perceive is not the persistence of an inner substance, but the ongoing causal linkage of events — a process that is coherent only because its parts are functionally and temporally related, not because they are grounded in a permanent core.

To say “I” is to refer to a momentary configuration within a vast web of interdependent processes. In Buddhist philosophy, this does not only apply to the so-called “person,” but to all phenomena. According to Abhidharma theory, the world is composed of dharmas — the smallest irreducible constituents of experience. The Five Aggregates themselves are comprised of such dharmas. These elemental events are not fixed objects or substances, but momentary processes that arise and pass away in dependence on conditions.

The implication of this view is profound: not only is the “person” a process, but so is everything that seems to interact with or shape that person. Each moment of perception, thought, or emotion arises from an intricate interplay between dharmas — external and internal, mental and physical. The current state of the Five Aggregates is shaped by countless other dharmas in the environment and mental continuum, and in turn, each aggregate influences the conditions for the arising of other dharmas.

This mutual influence is what Buddhism calls dependent co-arising (paṭicca-samuppāda). In this view, nothing exists independently; all things are part of interpenetrating causal flows. The identity we take to be “me” is simply one such temporarily coherent pattern. Recognizing this networked becoming dissolves the illusion of a solid essence. There is no thing to grasp — only process to understand.

Ethical implications of interdependence

This insight has profound ethical implications. If what we call “I” is inseparable from the rest of reality — shaped by and shaping the dharmas that constitute the world — then there is no absolute separation between myself and others, or between internal and external events. From this follows a rational basis for compassion: harming others is, in a very real way, harming oneself, since all beings and conditions are part of the same interdependent flow. Supporting and caring for others strengthens the conditions that nourish one’s own aggregates, just as creating suffering in the world inevitably reflects back into the stream of one’s own experience.

Compassion also makes pragmatic sense. Since the quality of the environment influences the arising of future dharmas, cultivating kindness, patience, and care helps generate beneficial conditions — both for others and for oneself. The moral imperative in Buddhism is not abstract; it is grounded in the direct interdependence between mental and physical processes. Acting ethically is not about upholding a command, but about shaping the very world — and self — that will be experienced next.

Beyond the aggregates? A note on the Yogācāra perspective

While early Buddhist analysis centers on the Five Aggregates and their impermanent, selfless nature, later Mahāyāna developments — particularly in the Yogācāra school — introduced a more layered model of consciousness. This includes the concept of the storehouse consciousness (ālaya-vijñāna), a background process that accounts for the continuity of karmic tendencies.

Though not part of the original skandha framework, this model does not contradict it. Instead, it deepens the analysis of consciousness by addressing how momentary processes might accumulate and persist without implying a permanent self. The ālaya remains conditioned, impermanent, and empty — in keeping with the doctrine of anatta.

A detailed discussion of the eightfold model of consciousness, including ālaya-vijñāna, will be topic of a follow-up article on the eight types of consciousness in the Yogācāra school. For now, it is important to note that the Five Aggregates remain a foundational framework for understanding the nature of experience in Buddhism. They provide a clear and practical means of deconstructing the illusion of self, while later developments like ālaya-vijñāna offer additional layers of insight into the complexities of consciousness and karmic continuity.

From analysis to liberation: The path of insight

The analysis of experience into the Five Aggregates is not a metaphysical speculation, but a pragmatic tool. In Buddhist thought, this framework is part of a broader diagnostic and therapeutic system: it shows what we mistakenly take as “self”, how this illusion arises, and how it can be overcome.

At the heart of this view is the recognition of the Three Marks of Existence (tilakkhaṇa):

- Impermanence (anicca): all phenomena, including bodily form, feelings, perceptions, intentions, and consciousness, are in constant flux.

- Non-self (anatta): nothing among these phenomena can be identified as a fixed, autonomous self, because all are impermanent and subject to change. What we take to be ‘self’ is always in flux, arising and passing away moment by moment without a stable core.

- Suffering (dukkha): clinging (upādāna) to impermanent, non-self phenomena inevitably leads to dissatisfaction, because what is constantly changing cannot serve as a reliable basis for lasting fulfillment or identity. The more tightly one holds on to what is unstable, the more one suffers when it shifts or disappears — as it inevitably must.

The skandhas help to dissect this clinging. They make visible what we normally take as a coherent self — showing instead that it is just a bundle of moment-by-moment processes. Similarly, the teaching of dependent origination (paṭicca-samuppāda) reveals that all experience arises from conditions, not from any underlying substance or essence. Nothing arises independently, and thus nothing stands alone as an enduring identity.

Together, the Five Aggregates and dependent origination illustrate what is often referred to as a process ontology: reality is not made up of fixed things, but of interrelated events. The self is not a substance, but a flow — a constantly changing configuration of physical and mental phenomena.

This insight into process is not merely philosophical. It underpins the Eightfold Path (ariyo aṭṭhaṅgiko maggo), the path to liberation taught by Siddhartha. Ethical conduct (sīla), mental training (samādhi), and wisdom (paññā) work together to reorient perception. Through this training, the practitioner learns to see the aggregates for what they are: impermanent, conditioned, and not-self. This direct seeing — cultivated in mindfulness (sati) and insight meditation (vipassanā) — gradually dissolves the illusion of an autonomous “I” that suffers and strives.

Thus, the Five Aggregates are more than categories of analysis: they are part of a liberative strategy. They expose the structure of delusion and offer a path to freedom — not by discovering some hidden core of identity, but by realizing that no such core was ever there to begin with.

To see this clearly is not to fall into nihilism, but to step into a new kind of clarity — one grounded in direct knowledge of the impermanent, interdependent nature of all things. Without a fixed self to defend, fulfill, or protect, suffering is no longer taken personally; desire loses its compulsive grip; and other beings are no longer seen as separate or opposed. Instead, one moves through the world with awareness, compassion, and equanimity. If there is no fixed self, how might one relate differently to suffering, to desire, or to others? This is the invitation at the heart of the Buddha’s teaching: to exchange illusion for insight, and in doing so, to awaken.

The awakening to non-self

This realization — the direct, experiential understanding that all phenomena, including what we call “self”, are impermanent and dependently arisen — is what Buddhism refers to as enlightenment (bodhi). It is not merely a philosophical concept or intellectual insight, but a deep transformation of the way experience is perceived and lived. In this moment of realization, the mind ceases to superimpose the illusion of permanence, ownership, or inherent identity onto the flow of phenomena. It no longer takes processes to be things, or events to be entities. Instead, it sees clearly — through sustained mindfulness and insight — that all things, including one’s own thoughts, emotions, and sense of identity, are dynamic, conditioned, and selfless.

Enlightenment, then, is the awakening from a misreading of reality (avijja). It is the recognition that suffering arises precisely because we relate to what is in flux as if it were stable and possessible. When the illusion of an enduring self dissolves, so too does the compulsion to grasp, defend, or secure it. What remains is not annihilation, but freedom — a luminous awareness unburdened by delusion, attuned to the moment-by-moment unfolding of life. In this way, enlightenment is not escape from the world, but seeing the world without distortion, and oneself not as a separate entity, but as part of its interdependent unfolding.

Understanding impermanence and non-self is, however, only half the journey. The deeper and more demanding part is to realize it in one’s own life — not as a belief or conscious understanding, but as a way of seeing and being. This realization is not reached through reasoning alone, but through a long process of retraining perception. That is why the Siddhartha offered not just doctrines, but practical tools: the Eightfold Path, especially meditation and mental discipline, are designed to gradually shift our habitual experience of reality. Enlightenment in this sense is not a supernatural event, but the culmination of a transformation in how reality is lived and known.

Conclusion

The Buddhist analysis of the self through the lens of the Five Aggregates offers a profound rethinking of human identity. Rather than assuming a metaphysical essence or enduring substance, Siddhartha Gautama directed attention to the processes that constitute experience. These five psychophysical aggregates — rūpa, vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, and viññāṇa — are not components of a hidden self, but the very phenomena from which the illusion of self emerges. They are dynamic, interdependent, and impermanent — and it is precisely our attachment to them, and the mistaken belief that they form a unified “I,” that gives rise to suffering.

This view differs sharply from much of Western philosophical tradition, which has historically sought a stable foundation for identity — whether in the soul of Plato, the thinking substance of Descartes, or the rational autonomy of Kant. Even where modern Western thought has challenged essentialism, it often remains tethered to the assumption that some core feature must underlie the notion of personhood. Buddhism, by contrast, proposes that continuity and coherence do not require substance. Instead, they emerge from causal interdependence — not only within the aggregates themselves but in relation to the entire field of phenomena, including what we conventionally call the environment, society, and others.

This shift has significant implications. If we truly accept that what we call the “self” is a conditioned process among other processes, it becomes difficult to sustain rigid boundaries between self and world, inner and outer, mine and not-mine. The Buddhist framework invites a different kind of ethical orientation — not based on moral absolutes or fixed duties, but on the pragmatic realization that well-being arises from understanding interdependence. To harm another is not just ethically questionable; it is ontologically incoherent if one recognizes that there is no isolated self to protect or promote.

At the same time, this view is not meant to remain theoretical. In its full articulation, it leads to a transformation in perception — what Buddhism calls bodhi, or awakening. When the aggregates are seen clearly as impermanent and selfless, and when dependent origination is directly known in one’s own experience, the illusion of self no longer takes hold. What emerges is not emptiness in the nihilistic sense, but clarity, compassion, and freedom. The insight dissolves the root of craving and fear, precisely because it uproots the false object — the “I” — that clings and fears.

Yet the Buddhist view also demands something from the practitioner: it requires us to give up a deeply ingrained assumption about who we are. It asks us to look, without presumption, at the very fabric of our experience and to recognize that what we habitually call “I” is not a thing, but a designation — a label placed upon a momentary configuration of conditions. This is not a nihilistic view. It does not deny the reality of experience, but reframes that reality as a continuous unfolding, never fixed, never final.

And so the question is left open, not as a rhetorical device, but as an invitation:

If there is no fixed self, how might you relate differently to suffering, to desire, to others — or even to the idea of who you are?

This is not a question to be answered quickly or abstractly, but one to be returned to again and again — in thought, in perception, in meditation, in the very movement of lived experience.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments