Dependent Origination: The interdependent nature of existence

The doctrine of Dependent Origination (Paṭicca-samuppāda in Pāli, Pratītya-samutpāda in Sanskrit) is one of the central tenets of Buddhist philosophy. It provides an explanation for the arising and cessation of suffering by illustrating the interconnected and conditional nature of all phenomena. This teaching negates the notion of a permanent, independent self and instead presents reality as a web of interdependent causes and conditions. The understanding of Dependent Origination is crucial to Buddhist thought and practice, as it directly relates to the cessation of suffering and the attainment of liberation (nirvāṇa).

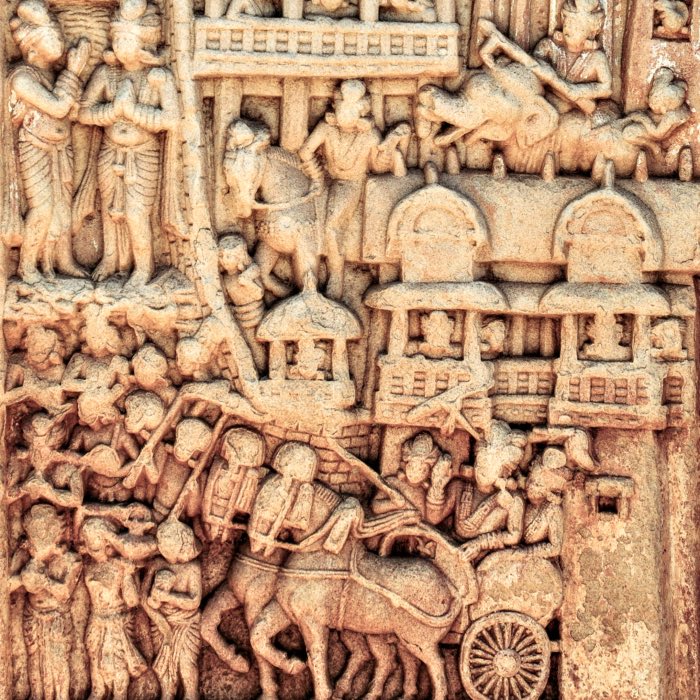

A stone relief of the Bhavacakra (Wheel of Life) at the Vipassana Meditation Center in India, established by a Myanmar-based Buddhist group. The Bhavacakra is a symbolic depiction of the cycle of existence and includes, among other elements, the twelve links of Dependent Origination. It serves as a powerful visual aid for understanding core Buddhist teachings. We will further explain the Bhavacakra in a dedicated section below. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC0 1.0; modified)

The principle of conditionality

At its core, Dependent Origination asserts that all phenomena arise due to specific conditions and cease when those conditions are no longer present. This principle, attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, is succinctly captured in the often-quoted formulation:

When this exists, that exists; when this arises, that arises. When this does not exist, that does not exist; when this ceases, that ceases.

– Majjhima Nikāya 79

Historically, this teaching emerged as a foundational response to the metaphysical speculations of Siddhartha Gautama’s time, particularly the eternalist and annihilationist doctrines found in Brahmanical traditions. By rejecting both a permanent self (ātman) and the idea of complete non-existence after death, the doctrine of Dependent Origination offered a Middle Way: phenomena — including personal identity — are neither eternal nor nihilistically void, but arise and pass away due to conditions.

This deceptively simple statement encapsulates one of the most radical insights of Buddhist thought: that existence is not grounded in any essence, substance, or first cause. Instead, all phenomena are contingent, relational, and impermanent. In this view, the self is not an independent entity but a composite of conditioned processes that arise and cease in dependence on one another.

Crucially, Dependent Origination is not a metaphysical speculation but an explanatory framework that underpins the Four Noble Truths. The first two truths — suffering (dukkha) and its origin (samudaya) — are expressed through this conditionality: suffering arises because of craving and ignorance, both of which depend on prior conditions. The third and fourth truths — cessation (nirodha) and the path (magga) — likewise depend on recognizing and reversing these conditions. Thus, Dependent Origination forms the structural logic behind the entire path to liberation.

This conditional matrix undermines metaphysical notions of permanence and supports the doctrines of impermanence (anicca) and no-self (anattā) — two of the Three Marks of Existence. It provides the conceptual architecture not only for understanding the emergence of suffering but also for dismantling its causes through ethical and contemplative practice.

The twelve links of Dependent Origination

Dependent Origination is traditionally expounded through a sequence of twelve interdependent links (Sanskrit: dvādaśa-nidānāni, Pāli: dvādasa nidānā) — traditionally known as the nidānas, or “causal links”, which describe the cycle of existence and rebirth (samsāra). Conventionally, these twelve nidānas are interpreted as a detailed elaboration of the second noble truth, tracing the causal process through which suffering (dukkha) arises. This process is not merely doctrinal but experiential — an analytical model for understanding how the continuity of suffering unfolds in individual experience. These links are not a strict linear progression but rather a dynamic and cyclical process:

| Nidana | Explanation1 |

|---|---|

| 1 | avidyā/avijjā – Ignorance: The fundamental misperception of reality, particularly regarding impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and the absence of a permanent self (anattā) |

| ↓ | |

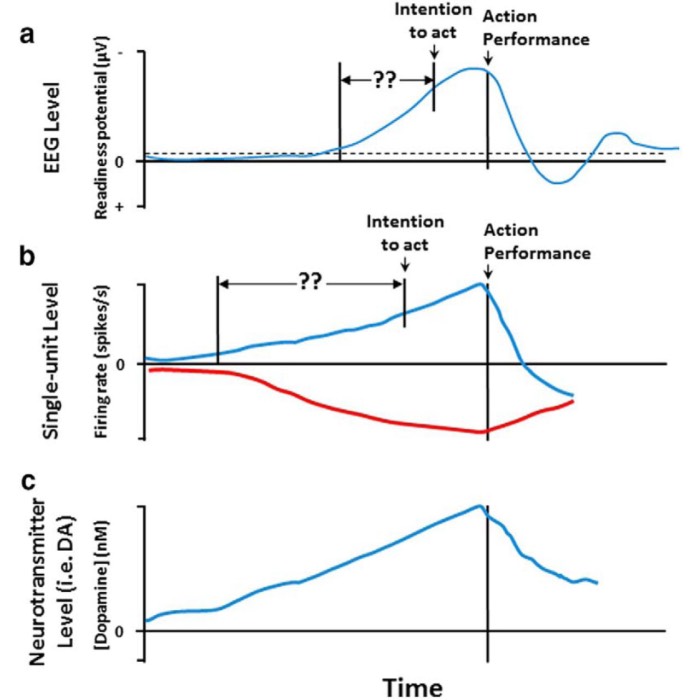

| 2 | saṅkhāra/saṃskāra – Volitional formations: Karmic predispositions and conditioned actions shaped by ignorance. These refer to the intentional mental formations that arise due to ignorance (avijjā), encompassing habitual tendencies and latent volitions. Shaped by past actions, they in turn condition future experiences, especially through their role in shaping consciousness. This concept aligns with the Buddhist understanding of karma as volitionally driven action that leaves ethical and psychological imprints on the mental continuum. |

| ↓ | |

| 3 | viññāṇa/vijñāna – Consciousness: The arising of awareness that is conditioned by prior volitional formations (saṅkhāra) and karmic imprints. In Buddhist thought, consciousness (viññāṇa) is not an isolated phenomenon but a process shaped by ethical and intentional actions from the past. These karmic imprints, carried forward in the mental continuum, influence the type and quality of consciousness that arises, serving as the foundation for the continuation of personal identity and experience across moments or even lifetimes. |

| ↓ | |

| 4 | nāma-rūpa – Name and form: The interaction of mental and physical processes that constitute an individual’s experience. The unreflective consciousness assumes that perceived forms are components of a solid, separate, and continuous core of being, to which we give names, reinforcing the illusion of a stable self where only impermanent processes exist. |

| ↓ | |

| 5 | saḷāyatana/ṣaḍāyatana – Six sense bases: The development of the faculties of perception — sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mind — through which consciousness engages with name and form (nāma-rūpa). These faculties condition how experience is filtered and identified, enabling the arising of contact with external and internal stimuli. |

| ↓ | |

| 6 | phassa/sparśa – Contact: The interaction between the sense organs and external objects, generating experience. This link arises from the prior development of the six sense bases (saḷāyatana) and nāma-rūpa (name and form), which together enable the faculties necessary for contact to occur. Without these preceding conditions — specifically, the differentiated senses and a mental-physical framework — no sensory contact can take place. Thus, contact (phassa) marks the first moment of cognitive engagement with the world, setting the stage for subsequent feeling and craving. |

| ↓ | |

| 7 | vedanā – Feeling/sensation: The sensations that arise from contact, categorized as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. These sensations result in an automatic and mostly unconscious evaluation of experiences, which forms the basis for subsequent craving or aversion. |

| ↓ | |

| 8 | tanhā/tṛṣṇā – Craving: The intense desire for sensory pleasures, existence, or non-existence. We have experiences with a sensory object and then want more of it. This wanting is what is called “thirst” (tanhā). In fact, we often seek to repeat the pleasant feeling that arose from the contact between our sense faculties and a particular object, even if we are already satiated. The ‘I-want’ or ‘I-don’t-want’ mind arises in response to these sensations. Craving can also be differentiated according to the six sense classes: craving for forms, sounds, smells, tastes, tactile sensations, and mental objects. According to Buddhist thought, craving is not necessarily to be forcibly extinguished, but to be understood, regulated, and ultimately released through insight and disciplined practice. |

| ↓ | |

| 9 | upādāna – Clinging: The deep attachment and identification with desires, objects, or views. Arising from craving (tanhā), clinging (upādāna) represents the stage where the mind fixates and identifies with what it desires or rejects. This link builds upon the previous by transforming the reactive momentum of ‘I-want’ or ‘I-don’t-want’ into a more entrenched grasping that solidifies one’s sense of identity and perpetuates the cycle of suffering. |

| ↓ | |

| 10 | bhāva – Becoming: The process of continued existence shaped by karma and clinging. Traditionally, this is interpreted as the karmic momentum that leads to a new rebirth, linking directly to the next nidāna, birth (jāti). However, from a psychological perspective, bhava can also be understood as the ongoing creation of personal identity. A kind of internal archive or memory of habitual reactions and intentions is formed — one that serves craving (tanhā) and attachment (upādāna). This ‘becoming’ is the consolidation of tendencies and dispositions that reinforce the continuity of the self, not only across lifetimes but also from moment to moment in a single life. In this sense, bhava represents the inner scaffolding of selfhood that emerges from our attachments and cravings. |

| ↓ | |

| 11 | jāti – Geburt: The arising of a new existence conditioned by past actions and mental formations. Conventionally, this refers to the literal birth into a new life, marking the continuation of saṃsāra under the influence of karmic momentum (bhava). However, from a psychological perspective, it can also be understood as the birth of a sense of self in a specific experiential context. The nascent archive of habitual reactions and intentions formed in bhava evokes a particular identity — an ‘I’ that sees itself as a subject within a personalized world. This identity is often centered around a specific desire or aversion, and gives rise to a subjective sense of ‘being someone’ in relation to a chosen object of experience. Thus, jāti also points to the moment-to-moment emergence of selfhood shaped by craving and attachment. |

| ↓ | |

| 12 | jarāmaraṇa – Aging and death: The inevitable suffering that arises from impermanence, culminating in the cycle of rebirth. Conventionally, this refers to the physical decay and death that mark the end of a literal life, as well as the continuation of saṃsāra through rebirth. However, from a psychological perspective, it can also be seen as the moment when the illusion of a substantial self faces the inevitability of change. The moment we cling to the feeling of a stable ‘I’, we begin to see this self as vulnerable — threatened in its autonomy and continuity. We suffer biologically through aging, illness, and death, but also psychologically, through grief, anxiety, or even joy, since all such phenomena are impermanent and cannot offer lasting satisfaction. |

Interpretations of the twelve nidānas

I personally tend to understand the twelve nidānas of Dependent Origination can be understood in both a conventional and a psychological sense.

From the conventional perspective, these links illustrate the process by which suffering arises across lifetimes. Beginning with ignorance and culminating in aging and death, the cycle describes how karmic actions and mental formations condition rebirth and continued existence within saṃsāra. Each link functions as both cause and effect, perpetuating the cycle of suffering unless actively interrupted through wisdom, ethical conduct, and meditation.

From a psychological perspective, the twelve links can also be interpreted as a description of how suffering arises within a single life, moment by moment. Ignorance gives rise to habitual patterns and reactive consciousness, which constructs a sense of self (nāma-rūpa) and engages with the world through the senses. Contact leads to sensation, which is automatically evaluated, generating craving and clinging. This results in the construction of a personal identity (bhava) centered around specific desires, giving rise to a sense of self (jāti) within a mental world. The eventual confrontation with impermanence (jarāmaraṇa) challenges this self-construct, leading to emotional and existential suffering.

Both interpretations converge on the insight that suffering does not arise from external conditions alone but from deeply conditioned patterns of perception and attachment. Whether understood cosmologically or experientially, Dependent Origination exposes the mechanisms of suffering and the possibility of liberation.

Breaking the cycle: The Path to Liberation

In both conventional and psychological interpretations, the cycle of samsāra can be described as the repetitive becoming and disappearance of experience. Traditionally, it refers to the literal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth across lifetimes. I tend to interpret samsāra from a more psychological perspective, where samsāra describes the continual arising and fading of a constructed sense of self, shaped by craving and clinging.

As long as ignorance and craving persist, this cycle continues uninterrupted. However, the structure of Dependent Origination reveals that if any single link in the chain is broken, the entire cycle collapses. For instance, removing ignorance (avijjā) halts the arising of volitional formations (saṅkhāra), thereby dissolving the subsequent chain that leads to suffering.

Buddhism offers a methodical approach to interrupting this chain through the cultivation of wisdom (paññā), ethical conduct (sīla), and meditative discipline (samādhi). The Noble Eightfold Path provides the practical framework for this: By cultivating right view, right intention, mindfulness, and other supportive factors, the conditioned patterns that sustain suffering are gradually dismantled, leading ultimately to liberation (nirvāṇa).

Dependent Origination beyond individual existence

The preceding discussion focused on the emergence of suffering as traced through the twelve nidānas, interpreted both conventionally as a cycle of rebirth and psychologically as the conditioned unfolding of identity and self-experience. Yet Dependent Origination also functions as a broader ontological principle — extending far beyond individual existence.

From this wider angle, Dependent Origination describes how all phenomena, not just the self, arise through contingent relationships. Thoughts, emotions, social structures, and even conceptual frameworks are not autonomous or fixed; they emerge due to causes and conditions and therefore lack intrinsic essence. I see this as a powerful framework for understanding the interdependence of mental, relational, and systemic processes alike.

In this sense, the doctrine also implies a subtle but far-reaching shift in how we view reality itself. Rather than imagining the world as made up of discrete, enduring things, Dependent Origination points to a continuous unfolding — a world composed not of substances but of processes, not of fixed entities but of interactions and events. There is no core “thing” behind phenomena (anatta); only patterned arising and ceasing, conditioned by other patterns. What we take to be stable and self-existing is, in truth, a temporary configuration of causes, arising moment to moment.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, this broader dimension of Dependent Origination becomes especially prominent. Nāgārjuna, in particular, deepened its implications by linking it to the doctrine of emptiness (śūnyatā): precisely because all things arise dependently, they are empty of any inherent nature (svabhāva). Emptiness is not a void or negation, but a recognition that everything is relational, impermanent, and without a fixed core.

Thus, Dependent Origination does not only reveal the internal mechanisms of suffering — it also offers a radically non-essentialist view of reality itself, dissolving not just the illusion of self, but the illusion of separateness in all things. The concept of interpenetration found in later Mahāyāna developments builds upon this view, and we will return to it in a forthcoming post as we explore how Nāgārjuna and subsequent thinkers articulated a vision of complete mutual dependency and non-duality.

Artistic representations

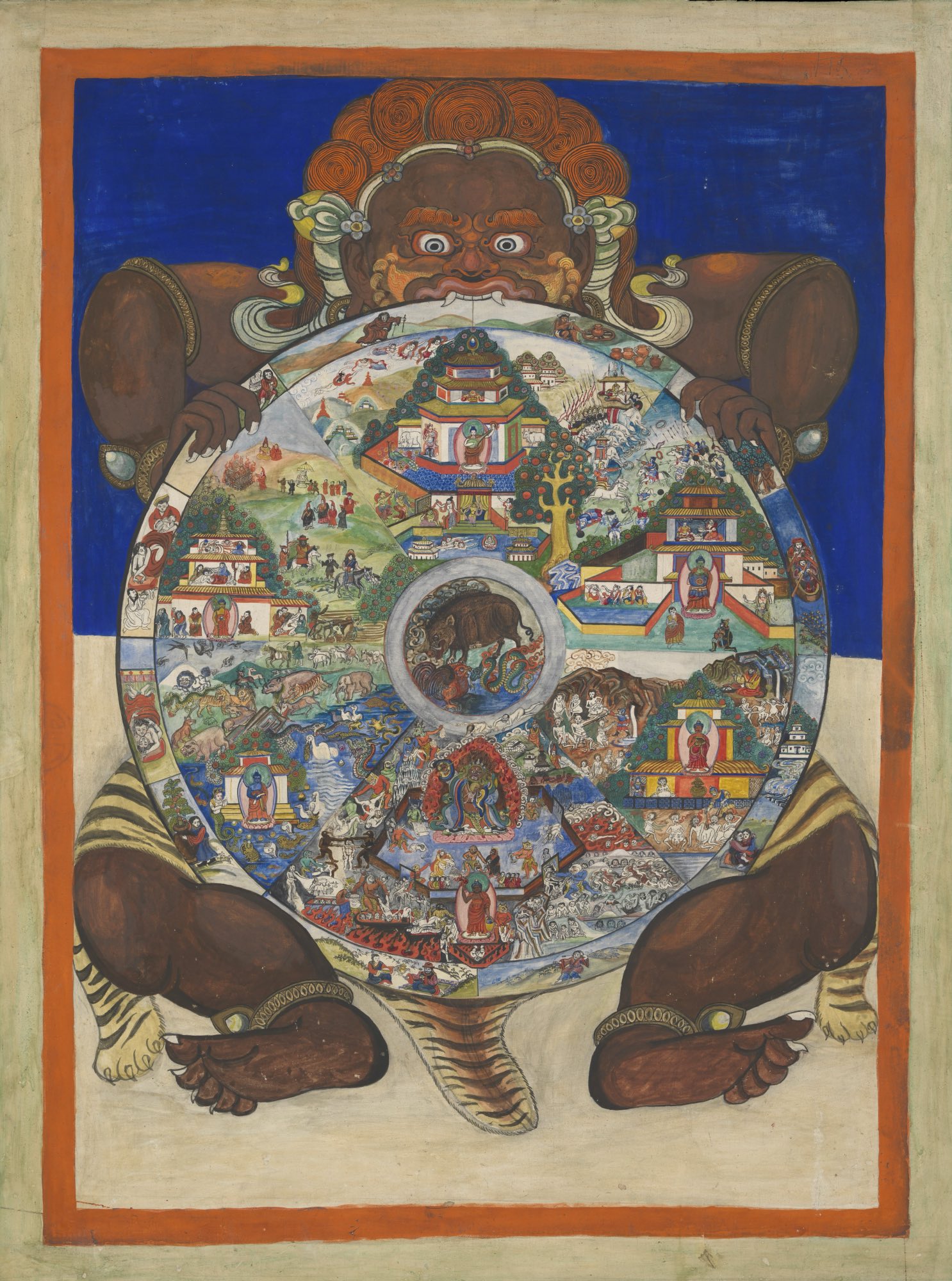

The doctrine of Dependent Origination has not only shaped Buddhist philosophy but has also found vivid expression in Buddhist art — most notably in the Bhavacakra or Wheel of Life. This symbolic image, often painted on temple walls or on Tibetan thangkas, represents the cycle of samsāra and includes a visual depiction of the twelve nidānas along its outer rim. Each link is portrayed through a conventional symbolic scene that captures its essential function in the chain of conditioned existence.

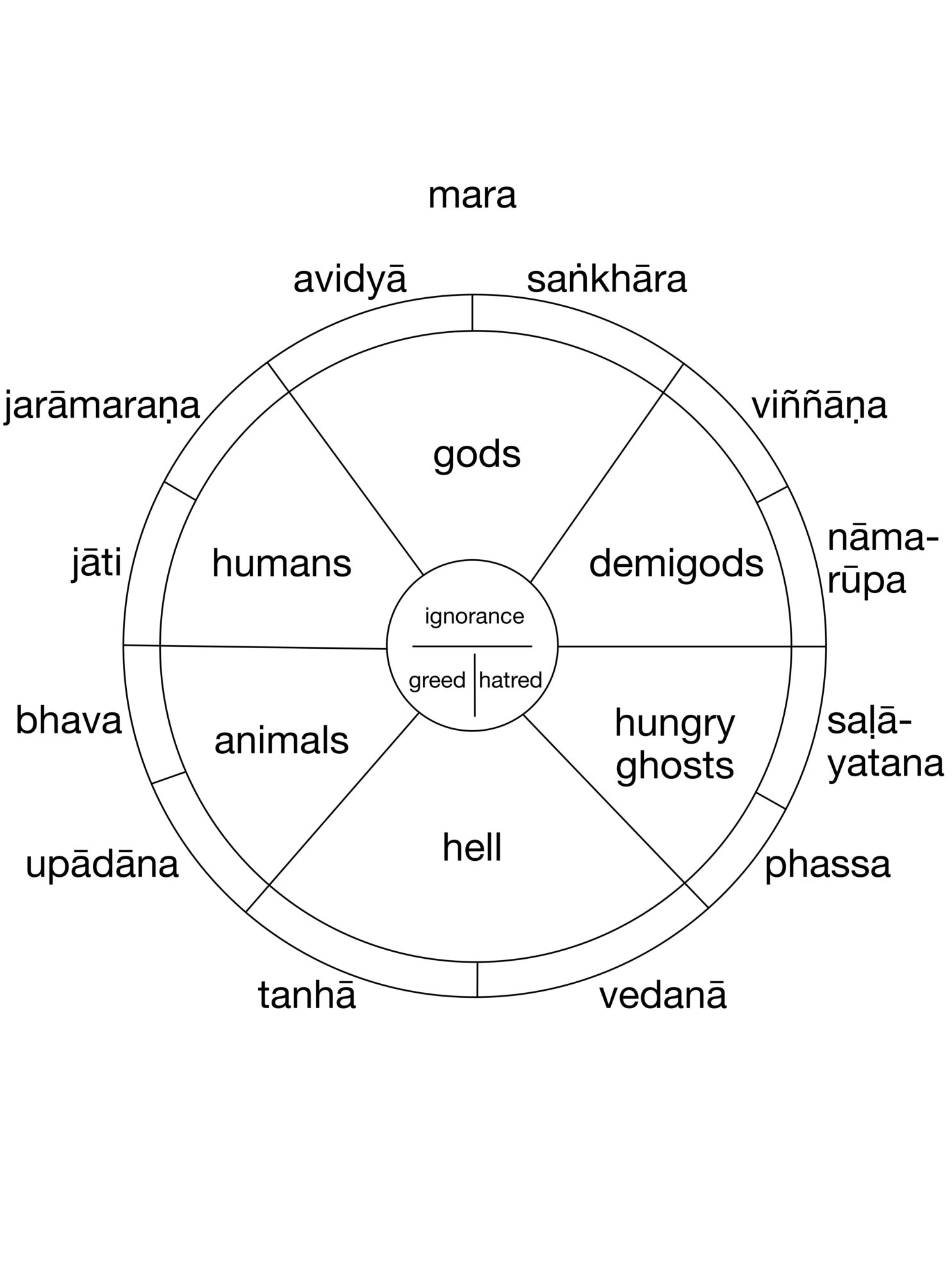

Bhavacakra at Punakha Dzong, Bhutan (right) and explanations of its symbolic elements (left). The twelve nidānas are depicted in the outer rim of the wheel, illustrating the cycle of existence and the interdependent nature of all phenomena. The center of the wheel typically features a pig, snake, and rooster, representing ignorance, hatred, and greed, respectively. These Three Poisons are considered the root causes of suffering in Buddhist thought. The wheel hub is often surrounded by images of the six realms of existence (gods, demi-gods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts, and hell beings), emphasizing the cyclical nature of life and rebirth. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CCBY-SA 4.0, modified and cropped)

The table below summarizes each nidāna along with its traditional symbolic representation in the Bhavacakra:

| No. | Pali/Sanskrit term | English term | Symbolic scene in the Bhavacakra |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | avijjā / avidyā | Ignorance | A blind person with a pot and a stick, groping towards the abyss from the safety of her home. Here, blindness represents ignorance |

| 2 | saṅkhāra / saṃskāra | Volitional formations | The intentions or volitional formations are represented by a potter who makes bowls and jugs for future use (= works of willpower). |

| 3 | viññāṇa / vijñāna | Consciousness | A monkey grasping fruit or jumping between trees. Programmed by the intention to act, consciousness takes on a new form of existence after each new cycle, like the depicted monkey swinging from one branch to another. |

| 4 | Nāma-rūpa | Name and form | Two people in a boat (mind and body working together). The new form of existence begins with the emergence of name and body, which refers to the spiritual and physical components of the person. These are dependent on each other like the two men in a boat and must remain together until the current is crossed. |

| 5 | saḷāyatana / ṣaḍāyatana | Six sense bases | A house, representing the body, with six windows, symbolizing the six sense faculties (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind) through which we perceive the world. |

| 6 | phassa / sparśa | Contact | A couple embracing or touching, representing the contact between the sense organs and their objects. |

| 7 | vedanā | Sensation | A person with an arrow in the eye. Sensation arises from the contact, often painful like the arrow in the eye, even more often tempting. |

| 8 | tanhā / tṛṣṇā | Craving | A person drinking or reaching for fruit. Desire or thirst (tanha) arises, represented by the jug filled with barley beer. |

| 9 | upādāna | Clinging | A monkey picking fruit or a person grasping objects. Desire, which is only satisfied in the short term, gives rise to an even stronger form of greed: attachment. You are now a slave to your passions. This form of existence is symbolized by the human being (sometimes also a monkey) who has grabbed a branch to pick fruit. |

| 10 | bhava | Becoming | A couple making love or a pregnant woman symbolizes the process of becoming. This link represents the karmic momentum that leads to a new rebirth, linking directly to the next nidāna, birth (jāti). |

| 11 | jāti | Birth | A woman giving birth or a child being born. This link represents the literal birth into a new life, marking the continuation of saṃsāra under the influence of karmic momentum (bhava). |

| 12 | jarāmaraṇa | Aging and death | Tied up in a cloth, the corpse is carried by a porter on his back to the burial site to be dismembered and eaten by vultures and jackals. This link represents the inevitable suffering that arises from impermanence, culminating in the cycle of rebirth. It also symbolizes the closure of the cycle of samsāra and the inevitability of death. |

These visual metaphors are not just illustrations — they serve as teaching tools to make abstract principles more accessible, especially in predominantly oral cultures. Each image is a mnemonic device, linking philosophical insights with relatable human experiences.

Conclusion

Dependent Origination provides one of the most comprehensive explanations of why suffering arises and how it can be brought to an end. At its core, it reveals that suffering does not originate from external fate or divine will but from deeply conditioned processes of ignorance, craving, and clinging. Whether viewed as a literal cycle of rebirth or as a moment-to-moment emergence of the imagined self, the twelve nidānas outline a law-like sequence that explains both the mechanics and the continuity of human dissatisfaction.

By tracing this cycle to its conditional roots, Buddhism proposes that liberation becomes possible when one of these links — particularly ignorance — is interrupted. This break opens the way toward the cessation of suffering (nirvāṇa) and a reorientation of perception grounded in insight, equanimity, and ethical awareness.

The doctrine of Dependent Origination marks a profound departure from many Western metaphysical assumptions. It does not assume a fixed essence, soul, or autonomous self, but places relationality and impermanence at the heart of its worldview. As such, it offers a radically different yet deeply coherent model for understanding the human condition. It not only explains why suffering persists but also empowers individuals with a systematic and experiential method for transforming their condition from within.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

-

The nidana designations are given in both Pāli and Sanskrit; when only one is given, the Pali and the Sanskrit terms are the same. The Pali terms are used in the Theravada tradition, while the Sanskrit terms are more common in Mahāyāna Buddhism. ↩

comments