Nirvana: The cessation of suffering in Buddhist thought

Nirvana occupies a central position in Buddhist philosophy as the ultimate goal of the spiritual path. Often translated as “extinction”, “cessation”, or “liberation”, Nirvana signifies the end of suffering, ignorance, and the cycle of rebirth known as samsāra. Rather than being a state of bliss in the conventional sense, Nirvana is characterized by the complete extinguishing of the fires that sustain cyclic existence: craving (tanha), clinging (upādāna), and delusion (moha). However, the conceptualization of Nirvana within Buddhism is intentionally elusive, resisting precise definitions and instead inviting reflection through negation, contrast, and experiential insight. In this post, we explore the multifaceted nature of Nirvana, its historical development, and its implications for Buddhist practice.

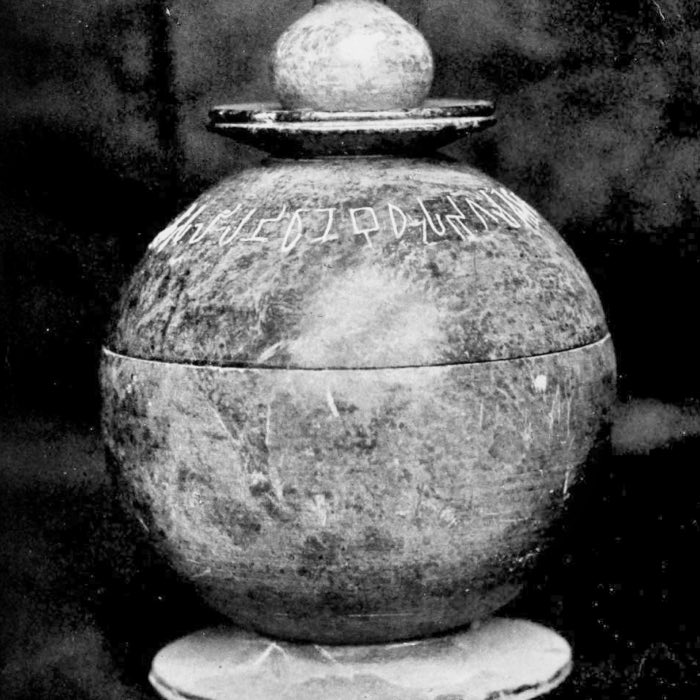

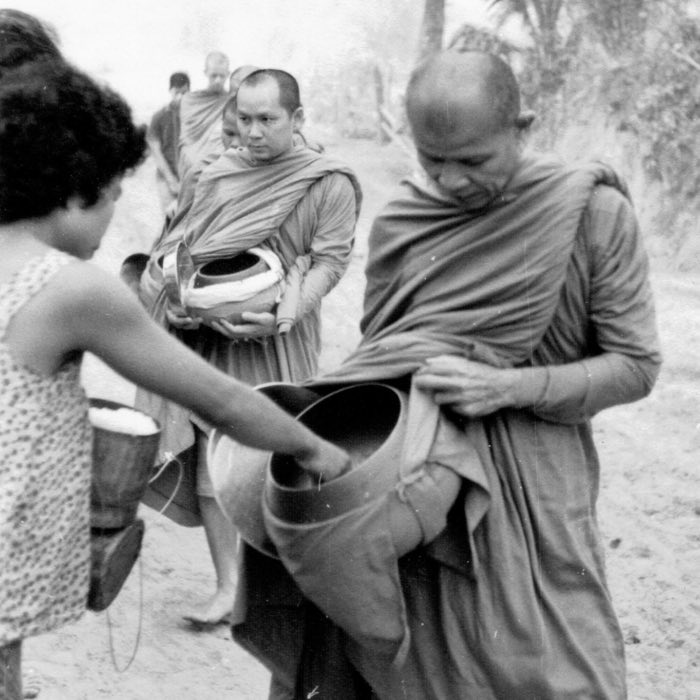

The passing away of the Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd-3rd c., schist. At the age of 80, the Buddha consumes a spoiled meal while traveling. Weakened, he lies down in a grove to die. He gives his monks encouragement one last time and gives instructions on how to deal with his mortal remains. Then the Buddha finally enters Nirvana. The relief depicts monks and laypeople gathering to mourn at the deathbed. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

The passing away of the Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd-3rd c., schist. At the age of 80, the Buddha consumes a spoiled meal while traveling. Weakened, he lies down in a grove to die. He gives his monks encouragement one last time and gives instructions on how to deal with his mortal remains. Then the Buddha finally enters Nirvana. The relief depicts monks and laypeople gathering to mourn at the deathbed. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

Etymology and philosophical framing

The term “Nirvana” (Sanskrit: Nirvāṇa, Pāli: Nibbāna) literally means “blowing out” or “quenching”, like the extinguishing of a flame. This image is evocative: it is not a place or a thing, but the absence of something — the absence of suffering and the conditions that generate it. In this sense, Nirvana is less a destination and more the negative imprint of samsāra. It marks the cessation of the causal chain outlined in the doctrine of dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda), where each link, from ignorance to aging and death, is disrupted. Through wisdom (prajñā) and meditative absorption (samādhi), one can see through the illusion of a permanent self and breaks the cycle of reactivity that sustains suffering.

Siddhartha’s silence on Nirvana

Importantly, Siddhartha Gautama did not frame Nirvana as a metaphysical heaven or a positive ontological realm. Rather, he avoided speculative metaphysics altogether when asked about the nature of Nirvana. In a number of canonical texts, he remains silent or redirects the question, emphasizing the practical task of ending suffering over theorizing about transcendent states. This strategic silence reflects a broader methodological commitment within early Buddhism to avoid metaphysical entanglements that might reinforce clinging to concepts. The point is not to construct a dogma, but to liberate.

The path of the Arhat in early Buddhist thought

In early Buddhist thought, the ideal of spiritual liberation is embodied by the arhat — the one who has extinguished all defilements and realized Nirvana. Nirvana is presented not as an external paradise or a metaphysical reward, but as the unconditioned reality (asaṃkhata), free from suffering, impermanence, and the delusion of a permanent self. This early soteriological model emphasizes personal liberation through insight (paññā), ethical conduct (sīla), and meditative discipline (samādhi). In early Buddhist thought, Nirvana represents a radically transcendent state beyond all conditioned phenomena, where the cycle of birth and death is fully broken. It is conceived not merely as the cessation of suffering, but as an unchanging reality that lies outside the realm of causation — permanently free from impermanence, dissatisfaction, and self-delusion. In this sense, Nirvana functions as both the telos and the metaphysical culmination of the Buddhist path, achieved through a disciplined withdrawal from craving and a gradual uprooting of all mental defilements.

Lived experience of Nirvana

However, this transformation does not mean that the empirical experience of life ceases to involve discomfort, change, or challenge. Even an arhat still feels pain, sickness, frustration, and emotional fatigue — just like anyone else. The difference lies not in the events themselves, but in the relation to them. The arhat no longer constructs a narrative of ownership around sensations or experiences. They arise, are seen for what they are, and pass without resistance or clinging. The world is no longer filtered through the lens of a possessive self.

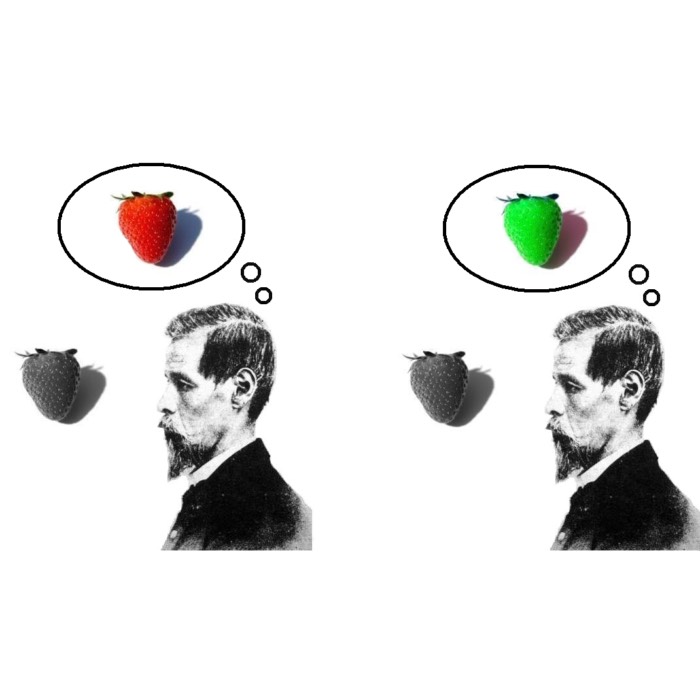

One common example to illustrate this shift in perception is that of a person mistaking a coiled rope in dim light for a snake. Upon seeing the shape, fear and panic arise. But when the light is turned on and it becomes clear that it is only a rope, the fear vanishes instantly. Nothing in the world has changed — the rope was always a rope — but the perception has shifted entirely. In the same way, the arhat awakens to see that the apparent threats and attachments of existence were never inherently real to begin with; they were projections sustained by ignorance. The suffering that depended on those misperceptions therefore ceases. Likewise, the arhat sees reality as it truly is: a flow of conditioned phenomena mistaken for personal threats and promises. This insight — into impermanence, impersonality, and the absence of a controlling self — removes the fuel that sustains suffering.

Pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral sensations still arise, but they are no longer met with attachment, aversion, or confusion. They pass through awareness like reflections across a still pond: visible, transient, and leaving no trace. Experience continues, but it is no longer personalized, no longer appropriated as “mine”.

Two-phase model: Nirvana in life and after death

Moreover, the arhat no longer generates karma. Their actions, though they continue to occur in the world, are no longer rooted in craving, ignorance, or ego-construction, and thus do not bear karmic fruit. This cessation of karmic production marks a decisive break in the chain of dependent origination that perpetuates samsāra. It is not mere detachment or emotional neutrality, but a structural transformation of how volition and causality function in the mind of the liberated being. What remains are the consequences of past karma, which still manifest as physical or experiential conditions — pain, old age, or social interactions — until these residual effects are fully exhausted.

This period is referred to as saupādisesa-nibbāna, or “Nirvana with remainder”. It is a liminal state: although the roots of suffering have been uprooted, the stream of conditioned existence continues briefly, propelled by earlier momentum. Upon the death of the body and the final extinguishing of all residual formations, the arhat enters anupādisesa-nibbāna, the final Nirvana, beyond all trace or remainder. This final liberation entails not only the end of suffering but the complete cessation of the five aggregates (skandhas), and with them, any further arising within the cycle of becoming.

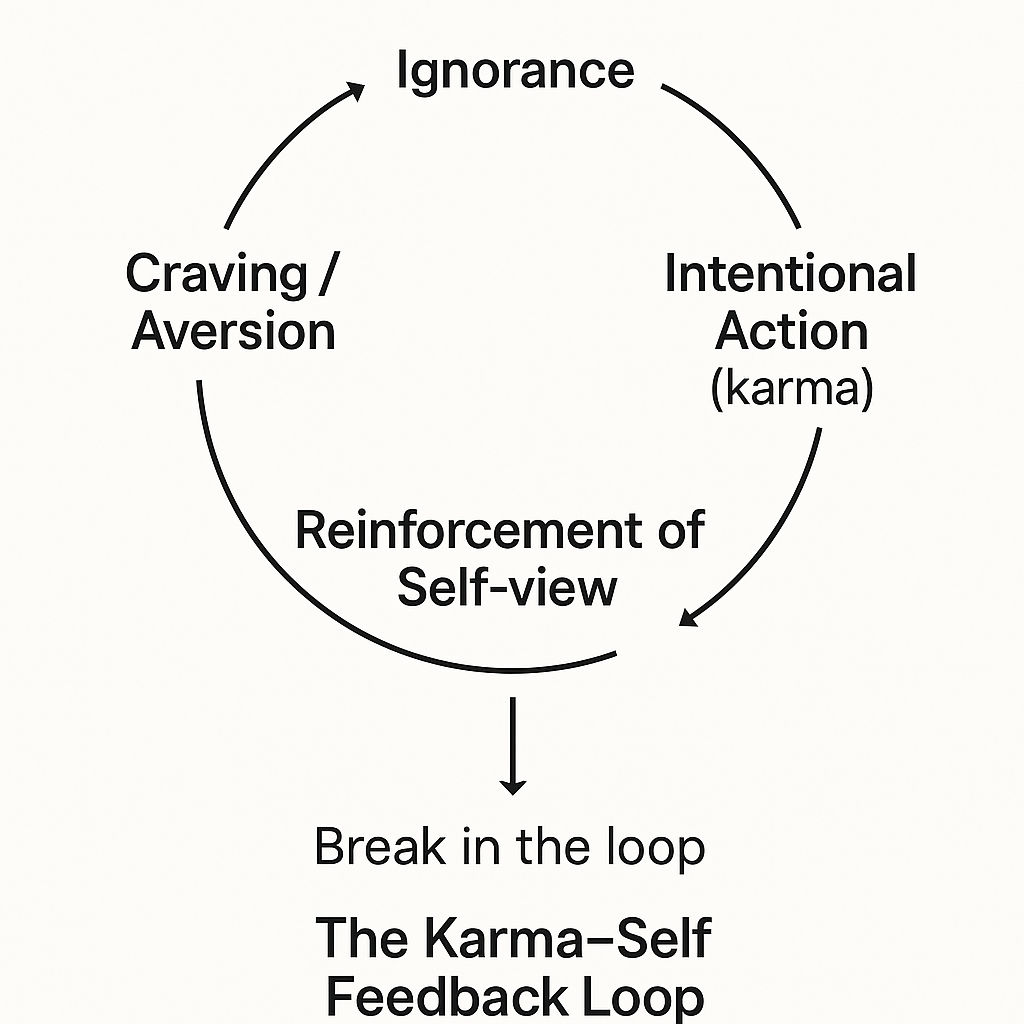

To fully understand why the cessation of karma marks such a profound transformation, it’s important to recognize how karma and the illusion of self reinforce one another. In Buddhist thought, intentional action (karma) arises from ignorance, craving, and aversion, i.e., mental states that presuppose a stable “I” behind action. Each such act not only conditions future experience but also reinforces the assumption that there is someone experiencing it. In this way, karma and the illusion of self form a mutually reinforcing loop: karmic action fuels the construction of self, and the belief in a self fuels further karmic action. As long as this loop continues, the cycle of rebirth (samsāra) is sustained. Nirvana represents the breaking of this loop. When craving and delusion end, intentional actions no longer arise from ignorance, and the process of “I-making” dissolves. The arhat, having severed this feedback loop, no longer generates karmic momentum – and with death, the last traces of prior conditioning cease as well.

Nirvana in life, therefore, is neither annihilation nor indifference, but an awakening to the fundamental unreality of the self and the release from the karmic forces that bind one to samsāra. It is a profound and irreversible shift in perspective: the world remains as it is, but it is no longer appropriated as “mine” or filtered through the fiction of a self. Experience flows, but nothing clings. The final Nirvana marks not a disappearance into nothingness, but the definitive end of the illusion that there was ever anyone there to begin with.

Summary: How karma sustains the illusion of self

Why liberation requires more than ending desire — it requires breaking the feedback loop of becoming:

- Karma refers to intentional actions shaped by craving, aversion, and ignorance.

- These actions are based on — and reinforce — the illusion of a stable “I” who acts and experiences.

- Each act embeds the idea of “I want”, “I fear”, “I suffer”, thus strengthening the mental habit of selfhood.

- This illusion of self becomes the seed for future karmic actions — and thus for further rebirth.

- The loop continues: intention → action → appropriation → reinforcement of self → new intention…

- Nirvana is the end of this cycle. When the roots of craving and ignorance are extinguished, no new karma arises.

- Without self-making, there is no becoming. Without becoming, there is no rebirth. What remains is freedom.

Beyond nihilism

The radical negations involved in describing Nirvana, its being beyond birth and death, beyond existence and non-existence, can easily lead to a misunderstanding: that Nirvana is simply a form of nihilism, a final dissolution into nothingness. However, this interpretation misconstrues the Buddhist understanding of Nirvana as realized by the arhat.

The cessation described in Nirvana is not the annihilation of something real, but the ending of illusion. It is the extinguishing of the flames of craving, ignorance, and clinging, not the erasure of an independent, enduring self — because such a self never truly existed to begin with. Thus, Nirvana does not represent the destruction of a real entity but the revelation of reality free from distortion.

Moreover, Buddhist sources describe Nirvana as blissful (sukha, the actual opposite of dukkha, suffering), peaceful (santi), serene (pīti), and unconditioned (asaṃkhata), qualities difficult to associate with pure nothingness, instead suggesting a state of profound clarity and openness – a positive affirmations of the nature of Nirvana. Rather than a collapse into void, it is the falling away of the false frameworks through which reality is habitually misperceived. It is more like the clearing of a fog that allows the vastness of the open sky to appear, rather than the disappearance of the sky itself.

In this sense, the realization of Nirvana should not be seen as a nihilistic negation of existence but as a transcendence of the categories of being and non-being altogether. It is liberation not into emptiness as absence, but into emptiness as openness and clarity — a state beyond all conceptual dichotomies, as experienced by the arhat who has completed the path.

The Bodhisattva ideal in Mahāyāna Buddhism

Mahāyāna Buddhism, which emerged several centuries after the earliest Buddhist teachings, represents a major shift in both philosophical emphasis and spiritual ideals. It is widespread across East Asia, especially in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, and is often characterized by its inclusivity, metaphysical depth, and the centrality of the Bodhisattva path. Unlike Theravāda’s focus on individual liberation through becoming an arhat, Mahāyāna reimagines the highest spiritual attainment as Buddhahood itself, complete awakening achieved for the sake of all sentient beings.

Within this tradition, Nirvana is not viewed as a final escape from samsāra, but rather as a realization that transcends and includes it. Some Mahāyāna texts articulate this through the doctrine of śūnyatā (emptiness), which deconstructs all conceptual dualities, including that between suffering and liberation, samsāra and Nirvana. From this standpoint, enlightenment is not an ontological shift into another realm, but a cognitive and existential transformation in how one perceives reality. We will further explore this idea of non-duality in the next section, where the very pursuit of Nirvana is questioned in light of the insight that all phenomena, including liberation itself, are empty of intrinsic essence.

As a result, the Bodhisattva ideal becomes central in Mahāyāna ethics and practice. Unlike the arhat, who may withdraw from the world after attaining Nirvana, the Bodhisattva deliberately chooses to remain within the world of birth and death, working tirelessly to liberate others. This ideal reorients the notion of Nirvana away from finality or withdrawal and toward an active, compassionate engagement with the world — enlightenment expressed through selfless service rather than solitary cessation.

Zen Buddhism: Direct realization of suchness

This Mahāyāna framing underscores a deeper shift: Nirvana is not simply a negation, but a mode of being in the world without attachment or aversion. The enlightened one acts without ego, yet fully within the world — manifesting compassion (karuṇā) alongside wisdom.

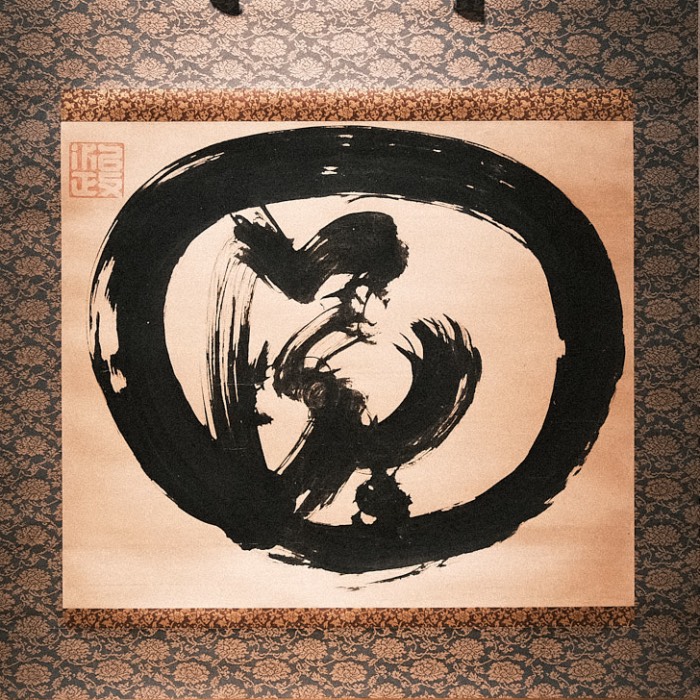

Zen Buddhism, a prominent Mahāyāna tradition particularly influential in Japan, Korea, and parts of China, builds on this idea through its radical emphasis on direct, non-conceptual experience. Rooted in Indian Dhyāna traditions and shaped by Daoist sensibilities, Zen rejects elaborate philosophical systems and instead values intuitive insight and the immediacy of present-moment awareness. The concept of tathatā (suchness), central to Zen, refers to perceiving reality exactly as it is, free from mental projections, judgments, and dualistic categories. Zen teachings often highlight that the very search for Nirvana can become an obstacle, as it reintroduces desire and goal-orientation into a practice meant to transcend them.

This leads to a unique tension in Zen thought: liberation is not about attaining something new but about fully realizing what is already the case. Hence, Zen kōans and meditation practices aim not at intellectual understanding but at breaking through conceptual habits to reveal the non-dual nature of experience. From this perspective, Nirvana is not apart from ordinary life but is expressed through awakened conduct within it — chopping wood, carrying water, and responding to the world without clinging or aversion. Zen thus exemplifies a radical internalization and deconstruction of the idea of Nirvana, aligning closely with the discussion in the next section on whether Nirvana should be regarded as a final goal at all.

Is Nirvana the final goal?

The common depiction of Nirvana as the “final goal” of Buddhism warrants careful scrutiny. While early texts describe it as the end of samsāra and the cessation of suffering, some Buddhist traditions and later interpretations problematize the teleological framing of Nirvana. In particular, Mahāyāna Buddhism often emphasizes that Nirvana and samsāra are not ultimately distinct. This idea stems from the doctrine of śūnyatā, or emptiness, which asserts that all phenomena, including the supposed dichotomy between bondage and liberation, are devoid of inherent existence. From this standpoint, any attempt to set Nirvana apart as a final destination inadvertently reinforces dualistic thinking. Instead, Nirvana is understood as a realization that transforms how one relates to all phenomena, without seeking escape from them. This reframing shifts the spiritual emphasis away from achieving a distant goal and toward awakening within the ongoing flux of conditioned existence. From this perspective, the pursuit of Nirvana is less about reaching a terminal state and more about cultivating a continual mode of being, free from attachment and delusion, within the flux of existence.

Moreover, the very concept of a “goal” may introduce a subtle form of craving or striving, which Buddhism identifies as a root cause of suffering. This paradox is especially pronounced in Zen traditions, where even the desire for enlightenment is seen as an obstacle. Thus, while Nirvana functions as a powerful heuristic and organizing principle for Buddhist practice, it may be more accurate to view it as a transformation of perspective rather than a final achievement.

Conclusion

Nirvana, in its broadest sense, is the extinguishing of the causes of suffering: craving, ignorance, and attachment to self. Rather than an external paradise or state of pleasure, it is best understood as a profound internal transformation marked by insight and freedom from reactivity. Different Buddhist schools have approached this goal in various ways — Theravāda stressing individual liberation, Mahāyāna extending it to a cosmic vision of compassion — but all converge on the notion that true liberation entails seeing through the illusions that bind us.

Importantly, Nirvana is not a state produced by causes or conditions. It is not the result of ethical behavior, meditation, or philosophical insight in the usual causal sense. Instead, Nirvana is often portrayed as a reality that was always present, obscured only by ignorance and craving. The practices of the Buddhist path serve not to “create” Nirvana, but to remove the obstructions that prevent its recognition — similar to wiping dust off a mirror that always had the capacity to reflect.

Moreover, Nirvana resists all conceptual categorization. In dialogues such as with the Brahmin Vacchagotta, Siddhartha Gautama refuses to describe the Tathāgata after death in terms of existing or not existing. These categories, grounded in our ordinary conditioned experience, simply do not apply. A helpful analogy for understanding this is the example of a visitor asking, after seeing the buildings, professors, and students, “But where is the university itself?” The visitor mistakenly treats the university as a separate object, rather than realizing it is the organized structure of all these elements. Similarly, asking whether an enlightened being “exists” or “does not exist” after death misapplies concepts suited to conditioned phenomena onto what lies beyond them. This avoidance of ontological assertions parallels apophatic (negative) descriptions in other traditions: Nirvana is described not by what it is, but by what it is not — unborn, unconditioned, unchanging.

The radical nature of Nirvana in Buddhist thought stands in stark contrast to many Western religious and philosophical traditions. In Christian theology, for example, salvation often implies eternal communion with a personal God in an afterlife. Here, identity persists, and relationality remains fundamental. Nirvana, by contrast, involves the dissolution of selfhood and the cessation of desire, not its fulfillment. Similarly, classical Western philosophy tends to valorize permanence, being, and rational comprehension. Buddhism, especially in its emphasis on impermanence (anicca) and the emptiness of all phenomena, offers a counterpoint that privileges process, flux, and experiential non-conceptuality.

From a critical perspective, the elusiveness of Nirvana can be seen both as a strength and a limitation. On one hand, it resists dogma, inviting personal insight and direct experience. On the other, its anti-metaphysical stance can be difficult to reconcile with traditions that seek coherent ontologies or moral teleologies. However, precisely in its refusal to posit a final truth or absolute being, Buddhism may offer a model more compatible with contemporary philosophical naturalism and psychology than many theistic frameworks. Nirvana does not offer meaning through belief in a higher power, but through a radical reorientation of how we relate to the world and ourselves. In this sense, Nirvana represents not a nihilistic void, but the liberation from the illusions that obscure the direct, dynamic nature of reality. That, perhaps, is what makes it not only unique, but compelling.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments