Buddha-Nature (Tathāgatagarbha) and the process of awakening

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, the concept of Buddha-Nature (tathāgatagarbha) has long served as a powerful metaphor for the innate potential of all beings to awaken. It affirms something simple but profound: that we do not need to become something else in order to attain liberation. We only need to see clearly what is already the case. Yet what exactly is Buddha-Nature? Does it imply a hidden essence beneath our everyday consciousness? Is it a kind of eternal self, contradicting the Buddha’s teaching of anattā (non-self)? Or can it be understood in a way that harmonizes with the process-based, selfless ontology that runs throughout Buddhist thought? In this post, we explore these questions and clarify the meaning of Buddha-Nature in light of the core teachings of Buddhism.

Buddha Daibutsu statue, Kamakura, Japan, cast in bronze in the year 1252 CE (Kenchō 4), during the Kamakura period. The statue represents Amitābha Buddha (Amida Nyorai), one of the five so-called Adi-Buddhas or primordial Buddhas. These Buddhas represent the primordial, non-dual, luminous nature of mind, which is closely associated with Tathāgatagarbha. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Not an essence, but a capacity

In traditional texts, tathāgatagarbha is often described in poetic, sometimes mystical language: the “womb” or “embryo” of the Buddha within every sentient being. But to take this literally would be misleading I think. In line with the Siddhartha’s rejection of any fixed self or inherent substance (svabhāva), Buddha-Nature is not a hidden entity. Rather, it is a potential — a capacity of the mind to awaken when its distortions are cleared away.

The Zen tradition captures this beautifully. In one sense, every being is already a Buddha — but not because they possess a secret, pure core. It’s because, when delusion falls away, the mind naturally reflects the world as it is. This is not the discovery of an inner essence, but the falling away of what distorts. Suchness (tathatā) is already present. It is the seeing that does not cling, the awareness that does not distort — the direct perception of the process-like, contingent nature of things, free from conceptual overlay. The only thing missing is our recognition of it.

Beneath the illusion of self

From a process-based view of reality, as developed in early Buddhist teachings:

- The self is not a substance but a stream of conditioned processes (skandhas).

- Suffering (dukkha) arises when we cling to this stream as if it were a fixed identity.

- Liberation is the realization that no such fixed identity exists — and never did.

So what lies beneath the illusion of self? Nothing substantial. But that does not mean nothing at all. What remains is clarity, presence, responsiveness without entanglement. This is what Buddha-Nature names.

Thus, Buddha-Nature is not the “true self” in any metaphysical sense. It is the absence of distortion, the readiness to see and live in accordance with suchness. It is what remains when grasping ceases. It is not a self behind the self, but a mind free of selfing.

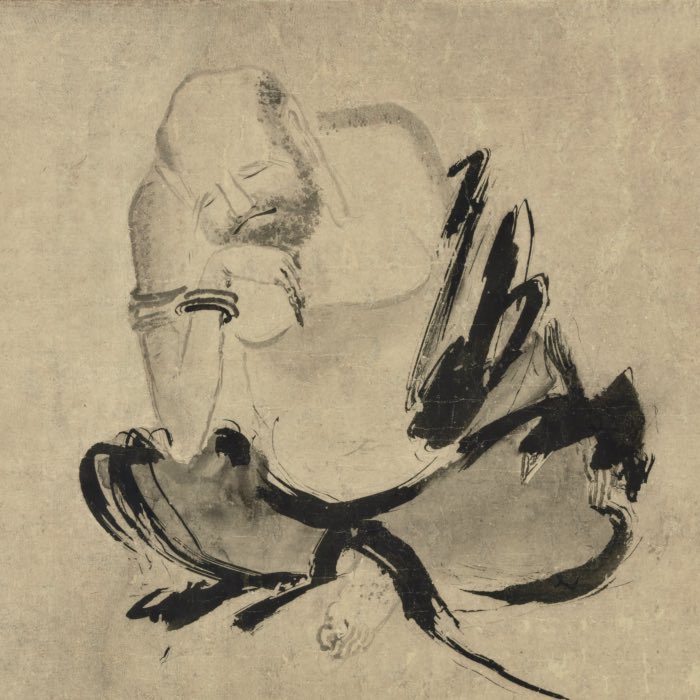

The Sky and the Clouds

A common image in Mahāyāna and Zen is that of the sky and clouds:

The mind is like the sky — vast, open, empty. The thoughts, emotions, identities, and delusions that obscure it are like clouds. They may appear dense, but they never touch the sky. The sky is never harmed. When the clouds clear, nothing new appears — only what has always been there.

This widely used analogy has no single source but is a traditional metaphor for the mind in Mahāyāna and Zen.

Your Buddha-Nature is the sky. Not a substance, but spaciousness. Not a soul, but the possibility of unobstructed seeing. It is not earned or given. It is uncovered.

Buddha-Nature and Tathatā

How does this relate to tathatā, the suchness of all things? Quite directly:

- Tathatā describes the nature of reality: interdependent, impermanent, without fixed essence.

- Tathāgatagarbha describes our capacity to perceive this nature directly.

In other words, the world is suchness, and the awakened mind sees it as such. Buddha-Nature is nothing other than the mind’s ability to awaken to tathatā.

So there is no contradiction between Buddha-Nature and the core Buddhist doctrines of anattā, anicca, and paťicca-samuppāda. There is only a shift in emphasis: from what reality is, to our ability to encounter it without distortion.

Why this matters

Understanding Buddha-Nature this way prevents us from falling into either of two extremes:

- The eternalist trap: imagining a true self or divine spark hidden within.

- The nihilistic trap: thinking that because there is no self, there is nothing at all.

Buddhism avoids both. There is no self. But there is awakening. There is clarity. There is a path. And there is a luminous way of being in the world that emerges when we stop interfering with it.

In this way, Buddha-Nature is not a metaphysical doctrine but an invitation: to trust that awakening is not far away. It is already here. It has always been here. It only waits to be seen.

Conclusion

The idea of Buddha-Nature (tathāgatagarbha) gains clarity when viewed not as a metaphysical essence but as a practical pointer toward our capacity to awaken. It affirms that the potential for liberation is present in every being — not as a hidden core, but as a possibility that becomes actual when the obscurations of craving, aversion, and delusion are relinquished.

Awakening, in this view, is not a distant goal or metaphysical leap, but the immediate and profound possibility of seeing clearly — perceiving things as they are. What we call Buddha-Nature is not something added to our being, but what becomes visible when delusion fades: the potential to live without distortion, to meet the impermanent world without grasping or resistance. It does not suggest a hidden essence or self, but names the mind’s inherent capacity to reflect reality — interdependent, transient, and empty of fixed identity — with clarity.

Far from contradicting the foundational teachings of anattā (non-self), anicca (impermanence), and paṭicca-samuppāda (dependent arising), Buddha-Nature brings them to life. It is not a metaphysical core, but the absence of selfing — a clear, unburdened openness that appears when clinging, ignorance, and projection cease. In this sense, Buddha-Nature does not describe something we must become, but points to the nature of awareness itself, once freed from confusion.

The critical strength of this view becomes clear when contrasted with much of Western thought. Western traditions, especially those influenced by Platonism or Christian theology, often emphasize a static soul or essence — something changeless that defines identity. In contrast, Buddhism’s process-based ontology dissolves the need for such an essence. We do not need to uncover a hidden divine spark — we only need to stop clinging to what obscures clarity. And unlike traditions that place awakening in the hands of divine grace or cosmic fate, Buddhism locates it in the sphere of personal responsibility and practical training: each individual can cultivate the path and realize awakening, not by appealing to external salvation, but by seeing through illusion and living in harmony with reality as it is.

And yet, Buddhism does not fall into nihilism. Buddha-Nature affirms that even in the absence of a self, there is the real possibility of joy, insight, and ethical transformation. The sky may be empty, but it can be filled with light.

In this sense, Buddha-Nature is not a dogma but a doorway: a way of trusting in the mind’s capacity to align with tathatā — with the world, just as it is. This alignment is not a transcendence of life, but a full participation in it. Awakening does not reveal a new reality, but the radiant simplicity of the one already here.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments