Tathatā: Buddhism’s view on reality as it is

In the Buddhist tradition, few concepts are as subtle, elusive, and yet foundational as Tathatā, commonly translated as suchness, thusness, or thatness. At first glance, the term may seem abstract or even redundant, but it plays a profound role in both philosophical inquiry and spiritual practice within Buddhism — especially in Mahāyāna thought. Tathatā refers to the ultimate nature of things, perceived directly, unmediated by conceptual thinking, dualistic judgment, or emotional overlay. It is not a description of something particular, but rather the way things are in their bare, uncontrived being.

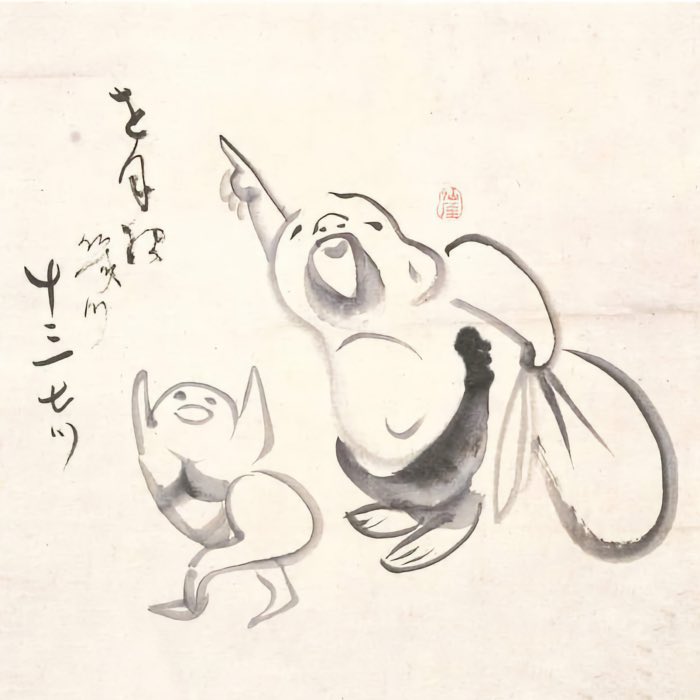

Wordless transmission of suchness. The depicted lotos flower held by one hand symbolizes a famous story in Zen Buddhism: Siddhartha holds up a lotus flower, silently expressing the true nature of reality. Mahākāśyapa, one of his disciples, is the only one who understands this gesture. He smiles, recognizing that Tathatā, the suchness of all things, cannot be spoken or taught — only seen. This story perfectly captures the ineffability of suchness while illustrating its direct experiential transmission. Source: Created with DALL•E.

Linguistic meaning and doctrinal background

The term derives from the Sanskrit tathā (thus, so) with the suffix -tā (–ness), suggesting “thusness” or “just-so-ness”. It is closely related to the Pāli term tathatā and echoes the way the Buddha himself was described as the Tathāgata — “one who has thus gone” or “one who has thus come”, depending on interpretation. Already in this epithet lies a mystery: what does it mean to “go” or “come” thus? It gestures toward a way of being that transcends ordinary perception and rootedness in conditioned existence.

In early Buddhist texts, Tathatā is often used modestly, almost synonymously with the dhamma — as a way to point to the true nature of things. However, in later Mahāyāna philosophy, particularly within the Yogācāra and Madhyamaka schools, Tathatā emerges as a pivotal concept. Here, it denotes the unfabricated, ineffable reality underlying all phenomena — beyond subject-object duality, beyond emptiness even, beyond any graspable “thing” at all.

Tathatā and the illusion of separateness

Ordinary consciousness, bound up in ignorance (avidyā), projects concepts onto the world. It interprets, judges, divides, and clings to dualities: good and bad, self and other, permanence and impermanence. These mental overlays obscure reality as it is. They cause us to see the world not directly, but through the veil of conceptualization. Tathatā, in contrast, points to what remains when this veil drops. It is the immediate presence of phenomena, just as they are — free of attachment, aversion, and delusion.

This does not mean that Tathatā — suchness — refers to some hidden essence, metaphysical Absolute — as sometimes imagined in Western mysticism — or static core of being. On the contrary, Siddhartha Gautama taught anicca (impermanence), anattā (non-self), and paṭicca-samuppāda (dependent origination). These foundational teachings emphasize that reality is not made of substances or fixed essences, but of processes — dynamic patterns that arise due to causes and conditions and dissolve again. Reality is a flowing field of interdependent phenomena, not a collection of separate things with intrinsic identity.

Seen in this light, Tathatā is not something apart from this flow. It is the direct experience of it. It is not the opposite of impermanence, but its face — the presence of impermanence, interdependence, and contingency, when no longer filtered through craving, aversion, or conceptual projection. To see things in their suchness is to see them as processes, unfolding moment by moment, without overlaying them with judgment or interpretation. Seeing things just as they are in the very moment.

So when Zen says “just sit” or “chop wood, carry water”, it is not pointing to a metaphysical essence — it is pointing to this process, right here, unadorned. It invites us to inhabit the moment without resistance or grasping, and to meet the world as it is — flowing, impermanent, empty of fixed identity — but undeniably present — arising right in front of us, in this moment.

In this way, Tathatā and process ontology are not different teachings but complementary views. One says: “see that everything is interdependent and always changing”. The other says: “see that clearly, and without distortion — just as it is”. Together they describe how reality actually works, and how it may be lived without illusion. The analysis of Siddhartha and the immediacy of Zen converge here: not in the search for essence, but in the awakening to impermanence — and to the luminous suchness of what is unfolding now.

This convergence protects against the trap of turning Buddhism into a mere analytical system: it reminds us that we are not meant to decode the structure of reality like detached observers, but to live in direct contact with its unfolding — perceiving suchness, not just theorizing it.

Tathatā and awakening

To realize Tathatā is to awaken. But not in the sense of gaining a new metaphysical insight or acquiring a special state. Rather, it is a dropping away of what obstructs the view. The Zen tradition is particularly fond of expressing this in stark, poetic terms: when a flower is seen as a flower, it is seen in suchness. When the wind blows, it simply blows. The awakened mind does not seek to stand apart from the world and analyze it — it is the world, fully immersed, fully attuned, without resistance or projection.

Tathatā does not exist somewhere else, nor is it hidden behind appearances. It is the appearances, once they are no longer taken as objects of craving or aversion. This is why, paradoxically, it is both utterly ordinary and profoundly transformative. The path to suchness is not a journey to another realm, but a return to what has always been right here, overlooked.

This insight is captured beautifully in the famous Zen saying: Before enlightenment, chop wood and carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood and carry water. Nothing has changed, and yet everything has changed. The wood and water are now seen in suchness. The mind is no longer split into observer and observed.

The inexpressibility of suchness

Because Tathatā is pre-conceptual, it resists definition. It is not a “thing” that can be labeled or known. In fact, the very attempt to define it risks undermining its essence. Language is a dualistic tool; it separates, distinguishes, and fixes meanings. But suchness is fluid, alive, and non-dual. Hence, the most authentic expression of Tathatā may not be verbal at all. It may be a silent gaze, a gesture, a poem that breaks grammar, or the sound of rain falling on a rooftop.

This is why many Mahāyāna and Zen masters resorted to paradox, silence, or direct pointing. The moment one speaks of suchness, it becomes something else. And yet, Buddhism continues to speak of it, not to define, but to invite. Every teaching, every kōan, every sutra is a finger pointing to the moon — but never the moon itself.

Tathatā in daily life

While the notion of suchness may appear philosophical or remote, it is deeply practical. To live in accordance with Tathatā is to live non-reactively, to let go of projections and preferences, to meet each moment as it arises. It does not mean passivity, but presence. Such living is compassionate, because it does not impose a self on others. It is wise, because it sees without distortion. It is free, because it is not caught in the grasping and pushing of ego.

In a world of relentless distraction, ideology, and identity-formation, the simplicity of Tathatā offers a radical alternative. It is not a denial of the world, but a profound affirmation of the world as it is — without clinging, without rejection, without delusion. In suchness, everything has its place. Even suffering, even imperfection, even death.

This perspective becomes clearest in the way we engage with everyday life. The depth of Buddhist insight unfolds not in abstract doctrine, but in the immediacy of how we perceive daily events. The world offers countless invitations to see through the lens of Tathatā, impermanence, and process-based perception. Let’s look at how this way of seeing can transform our experience of everyday situations, through a few practical examples:

A car

Conventional view: “That’s my car”, “I like that car”, “I want one like that.”

Process-view: The car is not a fixed object. It’s an impermanent assemblage of metals, plastics, labor, fuel, weathering, intentions, and economics. It exists temporarily as a useful configuration of processes.

Suchness-view: Simply “a car” — not owned, not desired, not judged. You see the shape, hear the sound, notice movement. It is what it is. Nothing added. You observe it arise in awareness and pass away.

“There is the car” — not “my car”, “a good car”, or “I want it.” Just what it is, now.

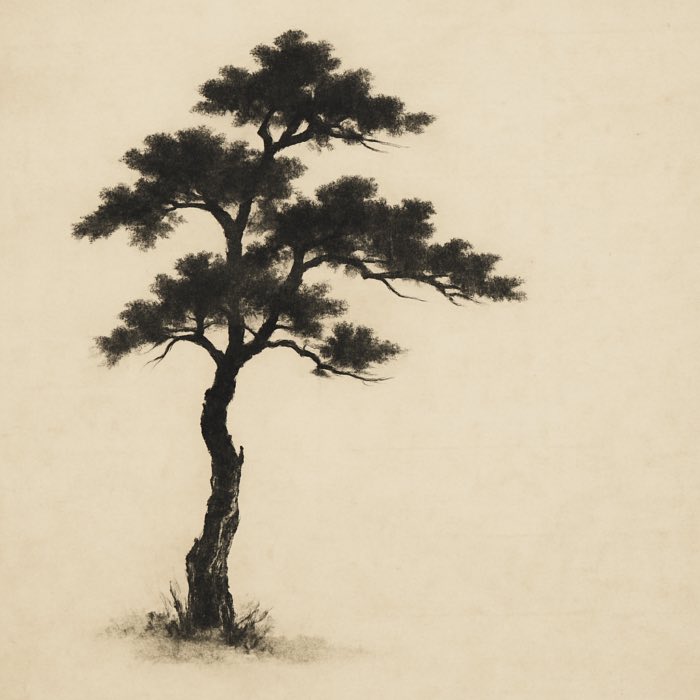

A tree

Conventional view: “That’s a strong old tree.” “It’s beautiful in the sunlight.”

Process-view: The tree is a process of growth: earth, water, light, time, decay. It is always becoming, not static.

Suchness-view: Just tree. No story, no need to describe or possess. Bark, leaf, wind in branches — vivid, alive, changing.

Not an object — a living presence, here and now.

A beautiful lake landscape

Conventional view: “So beautiful!” “I wish I could stay here forever.” “I need a photo!”

Process-view: Beauty arises from light, perception, memory, desire. Your reaction is not the lake — it’s your conditioned response to color, space, stillness.

Suchness-view: Beauty is seen — but not clung to. The lake, the light, the wind, your gaze — all come together in this moment. Nothing to grasp. Nothing to keep.

The landscape is not “for you.” It simply is. You let it arise, dwell, and pass.

The smell of wet earth while walking in the forest

Conventional view: “I love this smell”, “This reminds me of childhood”, “It’s peaceful here.”

Process-view: Smell is a momentary event: particles in the air stimulating olfactory nerves, generating sensation and memory. All dependent on rain, soil, your nose, your mood.

Suchness-view: A smell arises. Earth-wetness. No clinging, no narrative. It comes, fills awareness, fades. The forest breathes; you breathe with it.

This smell, now — fleeting, rich, ungraspable.

A happy child

Conventional view: “How joyful!” “I wish I had that innocence again.” “They’re lucky.”

Process-view: Joy arises and will pass. The child’s happiness is conditioned: maybe warmth, food, attention, or curiosity. It’s a dynamic stream, not a permanent state.

Suchness-view: The child is as they are — laughing, running, being. Not yours, not not-yours. Just a flash of joyful presence in the field of experience.

You see joy arise and disappear, without needing to hold or interpret it.

Seeing someone smiling

Conventional view: “They like me”, “That’s sweet”, or even “What are they thinking?”

Process-view: A smile arises due to physical, emotional, social causes. It may vanish in a moment. It’s not a thing, but a movement of the face, shaped by inner states and context.

Suchness-view: A smile appears — radiant, alive, vanishing. You don’t attach stories. You simply witness this transient expression of life.

“This smile, just now” — no need to grasp or interpret beyond its arising.

Someone is having a loud conversation on the phone

Conventional view: “How rude!” “He’s disturbing my peace.” “People these days…”

Process-view: Sound arises from vocal cords, air, distance, tension, emotion, context. Your reaction also arises — conditioned by mood, expectations, social norms.

Suchness-view: Just sound — noisy, complex, impermanent. A pattern in awareness. You see not only the sound, but your mind reacting. And in seeing it, the tension loosens.

A voice arises and passes — your frustration arises and passes.

A person not following the rules

Conventional view: “That’s unfair!” “Why don’t they respect the rules?” “This makes me angry.”

Process-view: Their behavior is conditioned — by their understanding, mood, history, maybe exhaustion or ignorance. Your aversion is also conditioned.

Suchness-view: A moment unfolds — this person acts, you observe. The urge to judge arises. You notice it. You may act (or not) skillfully — but without becoming entangled.

No self to protect, no need to defend. You respond, not react.

A person makes me angry

Conventional view: “They’re wrong!” “I have a right to be angry.” “This always happens!”

Process-view: Anger arises from a web of causes: expectations, habits, ego-defense. The other’s behavior, too, has its causes.

Suchness-view: Anger is seen not as yours, but as a transient process. The person is also seen in their complexity. The reaction arises, is noticed, and softens.

Anger comes, is seen, is allowed to pass — without owning it.

Thinking about a physics problem

Conventional view: “I have to solve this.” “This is difficult.” “But I enjoy working on demanding problems.”

Process-view: Thought arises — concepts, effort, memory, language. They flow in sequence, conditioned by study, mood, rest.

Suchness-view: You observe the thinking — not lost in it, not judging. The mind works. You watch it think.

Thinking happens. There is no thinker — just thought unfolding.

Working on code at work

Conventional view: “I’m focused on refining this solution.” “There’s a bug here — interesting.” “Let’s see where it leads.”

Process-view: Typing, logic, debugging — all flows of conditioned thought and action. Attention fluctuates. Frustration arises and fades.

Suchness-view: Keys click. Code unfolds. Frustration and insight alternate. You stay with the process, without grasping at results.

This line, this moment, this flow — seen and allowed.

Summing up

In all these, the core practice remains simple: see things as they arise, without adding a story. Recognize the process. Let them pass.

This does not mean detachment in a cold or removed way. On the contrary, it invites a kind of intimate clarity — presence without grasping. The world, seen in suchness, becomes more vivid, not less. It is not flattened by judgment, but allowed to shine in its immediacy. This is the everyday practice of awakening: not in retreat from life, but in seeing life clearly, compassionately, and without distortion.

Gladness of the mind (pamojja)

When we see things in their suchness, a quiet, satisfying kind of happiness may arise. It is not exaggerated or ecstatic, but a calm, satisfying kind of happiness. One might look at a tree, a passing stranger, or a shifting cloud and feel no need to label it good, bad, beautiful, or ugly — only a deep appreciation for how its parts have come together in this moment, forming exactly what is seen. This sense of just-so-ness, of things being complete without anything added or taken away, gives rise to a unique kind of joy.

In early Buddhist teachings, this is known as gladness of the mind (pamojja). It is the natural joy that follows when the mind is free from entanglement — when mindfulness and insight clear the turbulence of clinging and aversion. It is not something we create, but something that emerges when we stop interfering with what is.

Zen, too, expresses this experience in its own way — not through explanation, but through silence, simplicity, and poetic attention. It echoes this same experience in its preference for silence, simplicity, and direct seeing. The joy of suchness does not require explanation. It is like a teacup resting quietly on a table, or light falling across the floor. There is nothing missing. There is nothing to add.

This gladness is not separate from insight — it is the felt sense of liberation. When the mind no longer stands outside of life, trying to rearrange it, it settles into presence. And in that presence, there is peace — not because everything is perfect, but because everything is seen perfectly in its imperfection. That is the joy of being in accord with how things are.

Conclusion

Tathatā — suchness — is not a metaphysical riddle or mystical essence hidden beneath reality. It is reality, seen clearly. It is the immediacy of each moment when no longer distorted by judgment, craving, or conceptual overlay. In the Buddhist view, to live in accord with suchness is to live in alignment with anicca, anattā, and paṭicca-samuppāda — the recognition that all things are impermanent, without an inherent self, and conditioned, thus, interdependent. When we see the world not as a set of fixed entities, but as an unfolding pattern of causes and effects, we come into contact with its true texture: dynamic, interdependent, and fleeting — yet vivid and complete in each appearance.

This clarity is not merely philosophical. It is existentially transformative. To see a tree, a smile, or even a moment of anger in its suchness is to recognize it as part of an ongoing stream of reality. It is to drop the need to categorize, control, or cling — and instead to let things be as they are, in their arising and passing. From this insight comes not indifference, but intimacy. The world becomes more real, not less. Beauty deepens, even in transience. Suffering is met with compassion, not resistance.

Buddhism’s strength lies in its ability to articulate this vision with both precision and humility. Unlike many Western metaphysical traditions, which often seek an underlying substance or Absolute Being beneath appearances, Buddhism offers no such ground. What it offers instead is a method for seeing more clearly — not to uncover what is behind reality, but to see what is actually happening within it. While Western thought has often leaned toward either abstraction (idealism) or materialism (objectification), Buddhist practice urges us to experience the world directly, as a flow of contingencies. This view may seem less “grand”, but it is more liberating, because it requires nothing to be different than it already is.

Still, a critical point must be made. Process ontology — the recognition that all things are dynamic and interdependent — can, if handled only conceptually, become dry or overly intellectual. We risk becoming observers of impermanence rather than participants in it. This is where Tathatā becomes indispensable. It reminds us that insight is not just about what we see, but how we see — and how we live in relation to what we see. Suchness brings us back to the felt experience of reality, unfiltered. It completes the teaching not with theory, but with presence.

In this way, Tathatā protects the Dharma from becoming a cold system of analysis. It reminds us that the goal is not to dissect reality like a machine, but to become intimate with it — to see the rain falling on leaves, the steam rising from a bowl of tea, the face of a stranger, as they are. Just this, just now. Nothing more is needed.

And in that moment, perhaps, we find what the Buddha called freedom.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments