Daman Hongren: The fifth patriarch and the maturation of East Mountain Zen

Daman Hongren (弘忍; Japanese: Daiman Kōnin)) stands as one of the most influential figures in the formative history of Chinese Chán (Zen) Buddhism. As the fifth patriarch, he inherited a tradition that had begun to settle into communal structures under his teacher, Daoxin, and took decisive steps to deepen its philosophical articulation, broaden its pedagogical reach, and solidify its institutional presence. Hongren is most widely recognized as the teacher of Huineng (638–713), the Sixth Patriarch, but his own role is foundational in establishing what would later be called the “East Mountain Teachings”. These teachings emphasized seated meditation, direct awareness, and the inner realization of Buddha-nature, while avoiding elaborate metaphysics or scholastic commentary. Under Hongren’s guidance, Zen became not only a lineage of awakening but a concrete community, rooted in disciplined practice and shared insight.

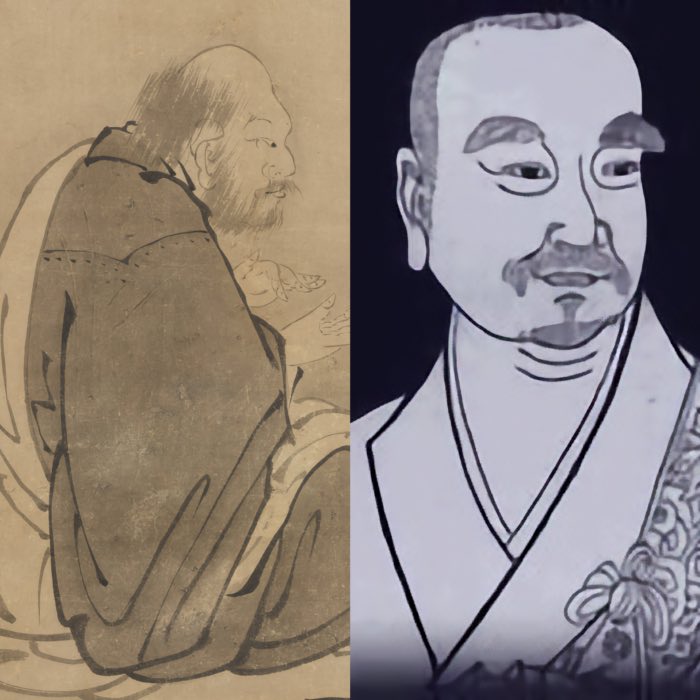

A painting of Honren, the fifth patriarch of Chán (Zen) Buddhism, unknown author. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) (modified)

Historical and biographical background

As with all early Chán patriarchs, many details of Hongren’s life are uncertain and overlaid with legends added long after his death. The following biographical account reflects the traditional Chán sources.

Childhood

Hongren was born in 601 CE in Huangmei, in what is now Hubei Province, during the Sui dynasty, with the family name Chou. His father is said to have left the family, and Hongren showed exemplary filial piety in supporting his mother. While records from the Chronicle of the Lankavatara Teachers and Disciples maintain this narrative, Chán scholar John McRae notes that the family residence was later converted into a monastery — suggesting that the Chou family was locally prominent and likely affluent. Furthermore, the mention of Hongren performing menial tasks gains significance only if such actions were unusual for someone of his background, reinforcing the idea that he came from the upper class.

Chán studies under Daoxin

At the age of seven or twelve, Hongren left home to become a monk and began his training under Dayi Daoxin, who is said to have recognized his spiritual insight immediately. According to tradition, the two met on a road in Huangmei:

Daoxin asked Hongren for his name.

Hongren replied: “I have essence, but it is not a common name.”

Daoxin asked: “What is it called?”

Hongren said: “It is the essence of Buddhahood.”

Daoxin responded: “Do you have no name?”

Hongren answered: “None, because the essence is empty.”

Impressed, Daoxin transmitted the Dharma and symbolic robe to Hongren, thus naming him the next patriarch.

Hongren’s early years at Mount Shuangfeng were spent in rigorous training and meditative discipline under Daoxin. After receiving the transmission, he remained there and gradually became its abbot, continuing Daoxin’s model of a stable monastic community centered on Zen practice. His leadership extended over several decades, during which the monastery became a thriving center for Chán training and a hub of religious activity.

The Annals of the Transmission of the Dharma-Treasure (Chuánfǎ Bǎojì, c. 712) portrays Hongren during this time as quiet, reclusive, diligent in humble duties, and steadfast in overnight meditation. It is said that he “never looked at Buddhist scriptures” but understood everything he heard. After about a decade of teaching, the record claims that “eight or nine out of ten ordained and lay aspirants in the country studied under him.”

Hongren remained with Daoxin until the latter’s death in 651.

Unlike his predecessors, who remained somewhat marginal to broader Chinese Buddhist society, Hongren’s community attracted significant attention, drawing students from across China and gaining respect even among elite laypeople and officials. This new level of influence, however, did not alter the core of his approach, which continued to emphasize inward realization and contemplative depth over ritual or textual study.

Teachings and philosophical focus

The teachings associated with Hongren form the intellectual and practical foundation of what would later be known as the “Northern School” of Zen, though the term itself is a later invention. Central to his approach was the view that the mind is fundamentally pure, and that delusion arises only from misperception and attachment.

Hongren taught that by calming the mind and turning inward, practitioners could directly perceive their Buddha-nature. His emphasis on continual self-awareness, meditative absorption (samādhi), and the letting go of discursive thought was deeply influential. He avoided metaphysical speculation, encouraging students instead to investigate the nature of mind itself.

Together with his teacher Daoxin, Hongren helped shape what became known as the “East Mountain Teachings”. These teachings represented an early school of Chán that prioritized seated meditation and inner observation over scholasticism or ritual. Though both figures were central, Hongren became the more prominent of the two, especially after relocating the community to the eastern peak of the Shuangfeng (“Twin Peaks”) mountain range.

This form of Zen was regarded by later generations as the authentic continuation of the patriarchal lineage and was promoted especially by his disciple Yuquan Shenxiu (c. 606–706), who became one of the most influential Buddhist monks of his time. The importance of Hongren’s teaching can also be seen in the compilation of the Treatise on the Essentials of Cultivating the Mind (Xiuxin Yao Lun) — likely collected shortly after his death — which represents the earliest surviving anthology of teachings from a Chán master.

He is often associated with this text, which outlines methods for focusing attention, observing thought, and abiding in clarity. While its authorship is uncertain, the treatise reflects the pedagogical style that shaped East Mountain practice: inward, direct, disciplined, and pragmatic.

Meditation practice

Although Hongren taught a wide variety of students, including Vinaya specialists, Sutra translators, and adherents of the Huayan and Pure Land schools, his own instruction centered on meditation. According to the Treatise on the Essentials of Cultivating the Mind, his core teaching was that the naturally pure mind is obscured by discriminative thinking, false ideas, and clinging to conceptual views. Dispelling these thoughts and maintaining a constant awareness of innate enlightenment would lead naturally to the experience of nirvāṇa.

Two meditation techniques are explicitly mentioned in the treatise. Hongren is said to have advised beginners: “Look where the horizon disappears beyond the sky, and visualize the character one (一). For beginners who find their minds distracted, focusing on this single mark can help stabilize attention. The character, a horizontal stroke, resembles a horizon and serves as a visual metaphor for the unity and clarity of the awakened mind.” The Chinese character for “one” is a single horizontal stroke, resembling a horizon and metaphorically representing the unity of mind and Buddha-nature.

He also taught that the meditator should inwardly observe the stream of consciousness: “Observe your own awareness calmly and attentively so you can see how it constantly flows, like running water or a shimmering mirage … until its fluctuations dissolve into peaceful stability. This flowing awareness will vanish like a gust of wind. When this awareness disappears, all one’s illusions will vanish with it.”

Hongren also placed increasing emphasis on the teacher-student relationship, viewing transmission not merely as ceremonial, but as the recognition of insight. His method favored subtle guidance over proclamation, encouraging students to observe their own minds until the illusion of a separate self fell away.

Institutional development and influence

Under Hongren’s leadership, the East Mountain monastery matured into a highly organized religious institution. While still emphasizing personal cultivation, it provided a relatively formal structure for training, with routines for meditation, instruction, and ethical conduct. This development helped stabilize the tradition and ensured its continuity.

Hongren’s impact was not limited to his own monastery. His reputation and the success of his community inspired the establishment of other Zen centers, and several of his students — most notably Shenxiu and Huineng (638–713) — would play central roles in the spread and evolution of Zen throughout China. The seeds of later doctrinal divergence were already present, but under Hongren, unity of purpose still prevailed.

His teachings created a bridge between the early Chán patriarchs and the later flowering of Zen schools. The East Mountain tradition, shaped by Hongren’s vision, formed the practical and intellectual basis for generations of Zen discourse.

Legacy and transmission

While the later tradition remembers Hongren largely as the teacher of Huineng (638–713), his own contributions were essential to the systematization of Chán. He did not merely pass on a lineage — he helped define its contours. His emphasis on meditative insight, mental clarity, and the intrinsic purity of the mind shaped not only the lives of his students but the institutional DNA of Zen itself.

Though historical details about his death are sparse, it is generally believed that Hongren passed away in the 670s. His legacy lives on through both the Northern and Southern schools of Zen, whose differences would become more pronounced after his death, but whose shared root in his teaching and structure remains evident.

Conclusion

Daman Hongren played a central role in transitioning Chán from its early, somewhat marginal form into a more defined and influential movement within Chinese Buddhism. He did not merely continue his teacher Daoxin’s efforts — he expanded them, both structurally and spiritually. By fostering a strong monastic community, formalizing meditative techniques, and articulating a clear pedagogical vision, Hongren laid the groundwork for generations of Zen development.

His teachings, encapsulated in the East Mountain tradition, reinforced the primacy of meditation, the unity of Buddha-nature and awareness, and the importance of internal observation over doctrinal speculation. Through his influence, meditation became more than a technique — it became the heart of practice, encompassing all aspects of life. Hongren’s pragmatic and non-scholastic approach set a tone that would remain distinctive in Zen history.

While often remembered for his connection to Huineng (638–713) and the eventual bifurcation of the tradition into Northern and Southern schools, Hongren’s own legacy stands on its own. His synthesis of personal cultivation, institutional coherence, and philosophical restraint made him a defining figure in early Zen. In shaping both the content and the container of Chán, he ensured that the tradition would not only survive but evolve, while remaining rooted in the experience of the present moment.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments