Sengcan: The third patriarch of Chán Buddhism and the spirit of equanimity

Jianzhi Sengcan (僧璨, Japanese: Kanchi Sōsan) is traditionally regarded as the third patriarch of Zen (Chán) Buddhism in China, the disciple and Dharma heir of Dazu Huike. Though little is known about his life, and few direct teachings can be reliably traced to him, Sengcan’s reputation in Zen tradition is anchored in both his role as transmitter of the lineage and his association with the celebrated Zen poem Xinxin Ming (Faith in Mind). His image, as transmitted through generations of Zen lore, reflects qualities of balance, equanimity, and profound inner stillness. In this post, we try to put together as much as possible about Sengcan’s life, including his teachings, the Xinxin Ming, and his legacy in the Zen tradition.

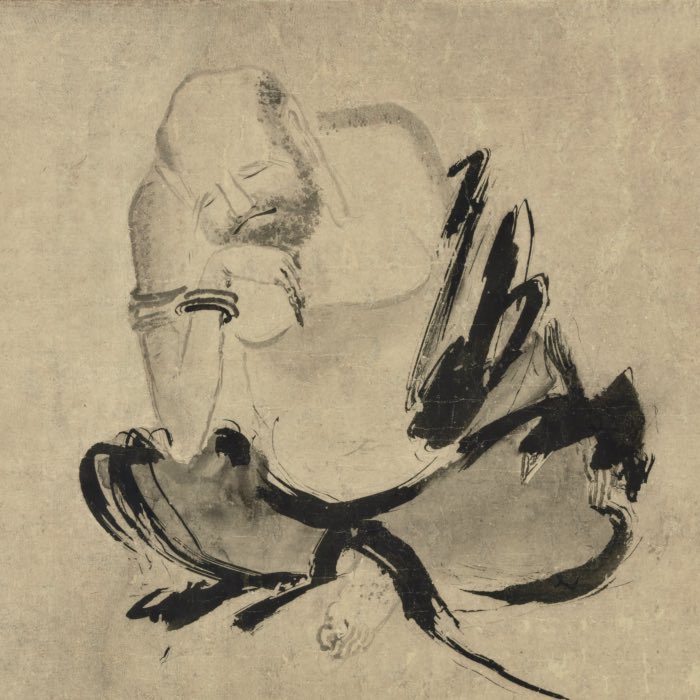

A picture of Sengcan, unknown author. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical and legendary biography

The available records about Sengcan’s life are sparse and often retrospective. His secular name and early life remain unknown. He likely lived during the late 6th and early 7th centuries, although the exact dates of his birth and death are uncertain. Tradition holds that he met Huike sometime during the persecution of Buddhism in 574 CE, when Huike had taken refuge in the mountains. Sengcan became Huike’s disciple and eventually received the Dharma transmission.

Some sources say Sengcan suffered from leprosy at the time of their meeting, and that Huike healed him as part of his spiritual acceptance. Whether literal or symbolic, this detail reinforces the notion that transformation in Chán often emerges through encounters that transcend ordinary distinctions — between health and illness, form and emptiness, teacher and student.

After receiving the Dharma, Sengcan reportedly lived a life of simplicity and seclusion, avoiding public recognition and institutional roles. He is said to have wandered for decades and finally passed on the lineage to Daoxin, the fourth patriarch, before dying on Mount Lu. His memorialization in Zen tradition emphasizes his humility, serenity, and the unadorned style of living that came to characterize early Chán values.

Sengcan and the Xinxin Ming (Faith in Mind)

Sengcan is most often linked with the Xinxin Ming (信心銘, Japanese: Shinjinmei), one of the earliest and most enduring texts of Zen literature. While modern scholars question whether Sengcan was truly its author, the association has remained firm within tradition, and the text is deeply expressive of his attributed spiritual orientation.

The Xinxin Ming is not a philosophical treatise but a poetic meditation on non-duality, equanimity, and the relinquishment of mental distinctions. Its most famous line — “The Great Way is not difficult for those who have no preferences” — encapsulates the essential Zen attitude of letting go of likes and dislikes, attachments and aversions, as obstacles to insight.

The poem invites the practitioner into a space beyond conceptual dualism, affirming that liberation comes through deep trust in mind itself, unclouded by striving or resistance. It reflects a maturation of the Zen ethos: calm, balanced, and deeply confident in the self-liberating power of mind when left undistorted.

Themes and teaching legacy

While no systematic doctrine is attributed to Sengcan, the teachings associated with his name emphasize qualities that would become central to Zen. These include:

- equanimity: A mental state free from preference and judgment, in which clarity arises not from grasping but from letting go.

- Non-duality: The insight that distinctions such as self and other, subject and object, are ultimately provisional and empty.

- Naturalness: A life lived in accord with the Tao — not through contrivance, but through the quiet alignment of inner and outer reality.

Through the Xinxin Ming and his exemplary conduct, Sengcan became a figure of stability and continuity. In contrast to the dramatic stories surrounding Bodhidharma or Huike, Sengcan’s legacy is understated. Yet this very quietness embodies the still center of Zen — the mind that does not cling.

Transmission and succession

Sengcan passed the Dharma to Daoxin (道信, Japanese: Dōshin), who would go on to further institutionalize Chán and establish a stronger monastic foundation for its continuation. This succession marks the point where Zen begins to evolve from a loosely associated group of itinerant practitioners into a more structured tradition with lasting institutional presence.

Even in this transition, the spirit of Sengcan’s teaching — its openness, simplicity, and reliance on inward clarity — remained vital. His transmission affirmed not only doctrinal continuity but also a continuity of attitude: the preservation of awakening as something lived rather than proclaimed.

Conclusion

Sengcan’s place in the early Zen lineage is defined less by dramatic episodes or doctrinal innovation than by a quiet, steady presence that helped establish the tone and attitude of Chán. As the third patriarch, he served as a bridge between the radical commitment of Huike and the institutional development initiated by Daoxin. His role was one of consolidation: maintaining the thread of direct transmission while embodying its essence in simplicity and serenity.

The themes attributed to Sengcan — especially equanimity, non-duality, and freedom from mental grasping — continue to resonate deeply in Zen practice. Whether or not he authored the Xinxin Ming, its spirit aligns with the legacy Zen remembers in him: a commitment to clarity without elaboration, insight without spectacle, and a mind at rest in its own nature.

Sengcan’s significance lies in his quiet radicalism. By exemplifying a life of retreat, humility, and internal stability, he gave form to the “Faith in Mind” that Zen demands — not as belief in a doctrine, but as trust in the awakened capacity of one’s own mind. In this sense, Sengcan is less a philosopher and more a presence — a figure whose contribution endures not through explanation, but through the stillness he came to represent.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments