Sokushin zebutsu: Mind itself is Buddha

The phrase sokushin zebutsu (即心是仏), “mind itself is Buddha”, is one of the most iconic statements in East Asian Zen thought. Originally attributed to Chinese Chán masters such as Mazu Daoyi, it encapsulates a radical immediacy: the very mind one possesses here and now is none other than Buddha. In Dōgen Zenji’s teaching, this expression is not merely affirmed but critically reinterpreted. Dōgen emphasizes that understanding “mind itself is Buddha” demands rigorous clarification: it is not an endorsement of complacency, conceptual identification, or static existence. Instead, it points to the dynamic, ever-unfolding nature of practice-realization.

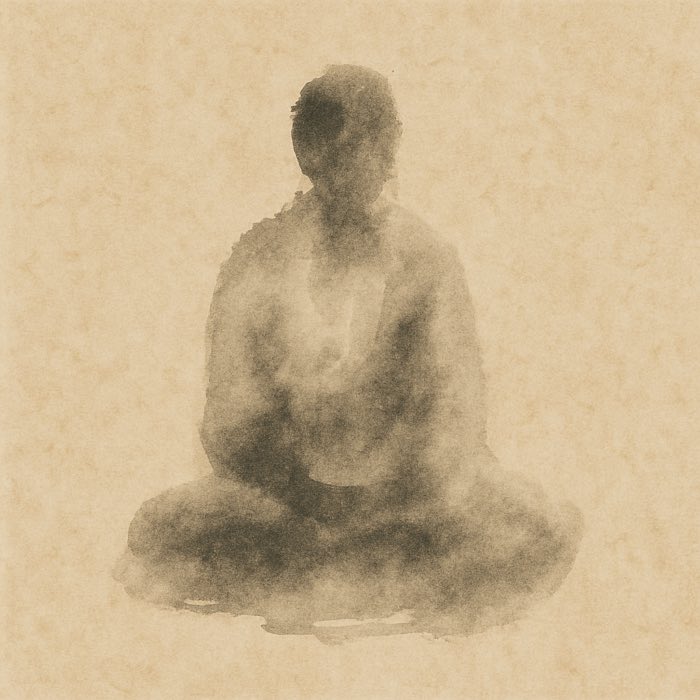

Zenga (Zen ink painting) evoking the phrase “Mind itself is Buddha” (sokushin zebutsu), showing the subtle emergence and dissolution of a face in empty space — a poetic gesture toward the inseparability of awareness and emptiness. Interpreted by DALL•E 2.

Historical background

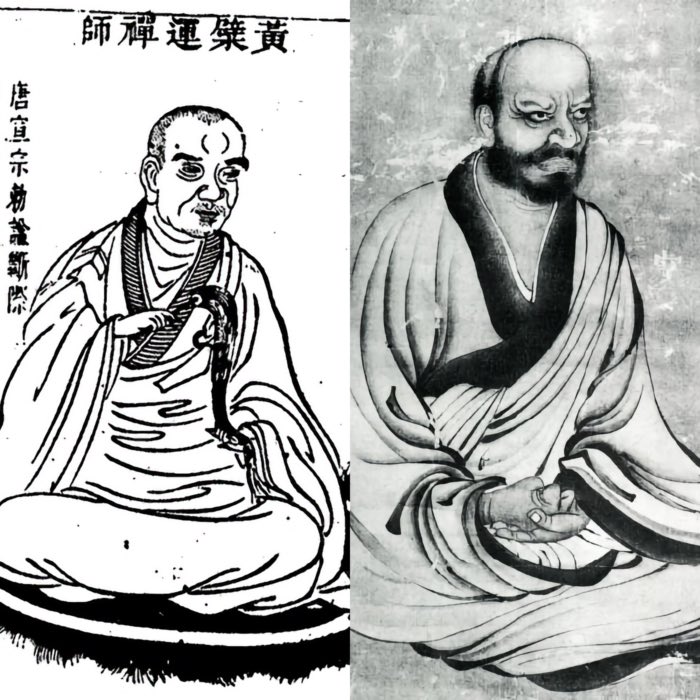

The phrase sokushin zebutsu first appears prominently in Chinese Chán dialogues, where it was used to shock students out of dualistic thinking. Teachers like Mazu emphasized that seeking Buddha elsewhere, apart from one’s present experience, was futile. However, as Chán developed, there arose misunderstandings: some took sokushin zebutsu to imply that ordinary, deluded mind was already sufficient, thus undermining the necessity of rigorous practice.

Dōgen, deeply aware of these pitfalls, engages the phrase with characteristic precision. His fascicle Sokushin Zebutsu in the Shōbōgenzō offers both an endorsement and a radical reworking of its meaning, insisting that “mind” and “Buddha” must be understood through the lens of continuous practice, not casual affirmation.

Dōgen’s interpretation of sokushin zebutsu

For Dōgen, “mind” (shin, 心) is not the personal, thinking mind tied to ego or conceptualization. Nor is “Buddha” (butsu, 仏) a distant deity or an ultimate state waiting to be attained. Rather, mind and Buddha are two ways of naming the same lived reality — the reality that manifests when one engages fully and sincerely in practice.

Thus, sokushin zebutsu points not to the ordinary mind entangled in delusion, but to the mind that has “dropped off body and mind” (shinjin datsuraku) and embodies the Buddha Way moment by moment. In this sense, to realize that “mind itself is Buddha” requires the complete letting go of grasping, dualistic thinking, and self-centeredness.

In Dōgen’s formulation, “mind” is dynamic, non-fixed, and inseparable from all phenomena. It is not a substance but an activity, the functioning of reality itself when experienced without obstruction. Therefore, Buddha is not something one becomes; Buddha is how reality functions when self-centered discriminations are relinquished.

Practice and sokushin zebutsu

Understanding sokushin zebutsu is not a matter of intellectual grasping but a matter of practice-realization (shushō ittō). In zazen, the practitioner directly experiences mind as dynamic, non-attached presence — neither clinging to thoughts nor rejecting them. This direct, non-conceptual engagement with mind is itself the expression of Buddha.

Importantly, Dōgen insists that affirming “mind itself is Buddha” without actual practice leads to delusion. The phrase must not serve as a justification for passivity. Only through sincere, embodied engagement can one realize the true meaning of this expression.

Philosophical implications

Dōgen’s interpretation of sokushin zebutsu challenges both naive quietism and metaphysical idealism. He avoids the trap of equating the conventional, discriminating mind with enlightenment. At the same time, he rejects the idea of Buddha as an abstract or transcendent entity separate from lived experience.

Compared to other Buddhist traditions emphasizing stages of purification or doctrinal attainment, Dōgen’s view insists on immediacy, relationality, and embodiment. His approach resonates with certain aspects of phenomenology, particularly in the way experience is not mediated by fixed subject-object structures. Yet Dōgen surpasses Western models by grounding experience in the non-dual, dynamic unfolding of reality rather than isolated subjectivity.

Sokushin zebutsu in the Shōbōgenzō

In the Sokushin Zebutsu fascicle, Dōgen deconstructs simplistic readings of the phrase. He draws on various Chán dialogues to illustrate that mind as Buddha is not the static possession of an individual but is realized through the ceaseless, dynamic activity of the Way.

He writes:

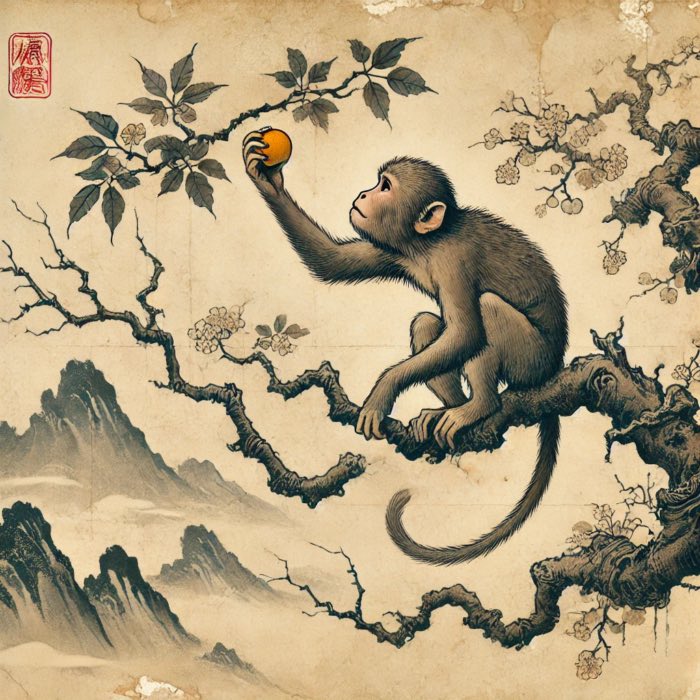

“The ‘mind’ of the mountains, rivers, and earth is nothing other than the mountains, rivers, and earth. Beyond that, there are no waves, no foam, no wind, and no smoke. The ‘mind’ of the sun, moon, and stars is nothing other than the sun, moon, and stars. Beyond that, there is no mist and no haze. The ‘mind’ as life and death, coming and going, is nothing other than life and death, coming and going. Beyond that, there is no delusion and no enlightenment. The ‘mind’ of hedges, walls, tiles, and pebbles is nothing other than the hedges, walls, tiles, and pebbles. Beyond that, there is no mud and no water. The ‘mind’ of the four elements and the five skandhas is nothing other than the four elements and the five skandhas. Beyond that, there is no horse-will and no monkey-mind ([the horse symbolizing restless will and the monkey symbolizing the complicated intellect]). The ‘mind’ of a chair or a whisk is nothing other than the chair or the whisk. Beyond that, there is no bamboo and no wood.

And because it is so, ‘the mind here and now is Buddha’ is the purity of ‘the mind here and now is Buddha.’”

Here, Dōgen underscores the inseparability of mind and the myriad phenomena of the world, challenging any lingering attachment to a metaphysical or internalist conception of mind.

Conclusion

Sokushin zebutsu in Dōgen’s Zen redefines the relationship between mind and Buddha as a dynamic, non-dual activity. Rather than equating ordinary, deluded mind with awakening, Dōgen reinterprets the phrase to emphasize the necessity of continuous, embodied practice. Mind as Buddha is not a static truth to affirm, but a reality to be enacted and sustained through wholehearted engagement in zazen and everyday life.

This perspective challenges both passivist interpretations that undermine discipline, and metaphysical views that abstract Buddha into a transcendent ideal. Instead, Dōgen’s view centers on relational immediacy: the mind that is Buddha is realized in the dropping away of self-referential constructs and in attunement to the unfolding of reality itself. It is not a matter of possession or attainment, but of active, unceasing practice in which awakening is continuously lived rather than claimed.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Dogen Zenji, Shobogenzo – Die Schatzkammer des wahren Dharma-Auges, 4 Bände, 2013, Verlage: Kristkeitz Werner, Übersetzung: Ritsunen Gabriele Linnebach, Gudo Wafu Nishijima, ISBN: 9783921508909

- Dogen Zenji, Unterweisungen zum wahren Buddha-Weg. Shobogenzo Zuimonki (2011), Verlage: Kristkeitz Werner, ISBN: 9783932337680

- Dogen Zenji, Hōkyōki, 2020, Angkor Verlag, Übersetzung: Guido Keller, Taro Yamada, Hidesama Iwamoto, ISBN: 9783943839821

- Dogen Zenji (Autor), Guido Keller (Übersetzer), Taro Yamada (Übersetzer), Eihei Shingi - Regeln für die Zen-Gemeinschaft, 2022, BoD – Books on Demand, ISBN: 9783988040008

- Dogen Zenji (Autor), Guido Keller (Übersetzer), Eihei Kôroku, 2017, Angkor Verlag, ISBN: 9783936018936

- Shohaku Okumura, Die Verwirklichung der Wirklichkeit - «Genjokoan» - der Schlüssel zu Dogen-Zenjis Shobogenzo, 2014, Kristkeitz, ISBN: 9783932337604

comments