Mushin: The Zen state of no-mind

Mushin (無心), typically translated as “no-mind” or “without mind”, refers to a pivotal mental state in Zen where the practitioner acts without hesitation, calculation, or attachment to thought. The term is widely known not only within Zen but also in disciplines influenced by it — such as the Japanese martial arts and calligraphy — where it denotes a fluid, spontaneous presence. However, in its deeper Buddhist sense, mushin points to a condition of mind unclouded by grasping, aversion, or conceptual elaboration. It is not a loss of awareness, but its refinement: pure attention unobstructed by egoic interference.

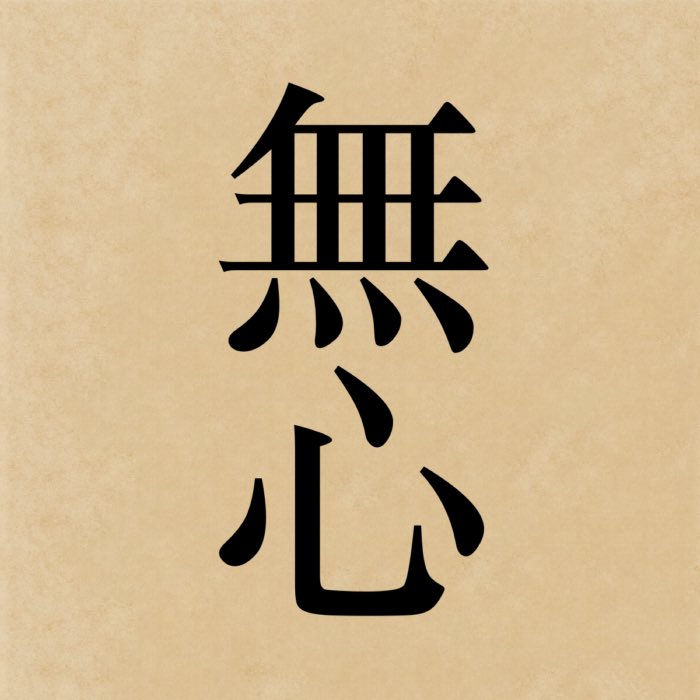

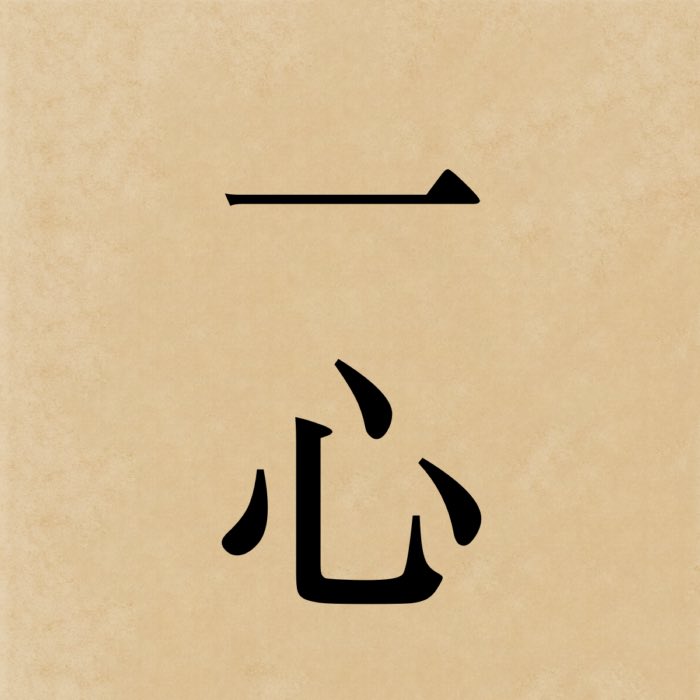

The kanji 無心, which reads mushin in Japanese, literally means “no-mind”. The first character, 無 (mu), means “none” or “without”. The second character, 心 (shin), means “mind” or “heart-mind”. Together, they convey the idea of a state of mind that is free from attachment and reactivity.

Meaning and etymology

The Japanese term mushin is composed of two characters: 無 (mu), meaning “none” or “without”, and 心 (shin), meaning “mind” or “heart-mind”. It refers to the absence of a self-centered mind – a condition where the habitual internal dialogue, emotional attachments, and reactive patterns have quieted. Thought may still arise, but it no longer dictates action or distorts perception.

Unlike a blank or vacant state, mushin is a clarity of mind that allows for precise and responsive engagement with the world. This resonates with the Buddhist ideal of upekkhā (equanimity), as well as with sati (mindfulness), where one observes arising phenomena without judgment or identification. The “no” in no-mind does not negate mind altogether but indicates the absence of fixed viewpoints and reactivity.

Mushin in practice

Mushin is most often associated with states of deep meditative absorption or moments of spontaneous action. In zazen, when thoughts lose their pull and attention stabilizes, the practitioner may enter a state where awareness is effortless and non-reactive. This is not induced by suppression, but by non-interference — thoughts and sensations arise and pass without being turned into narratives.

Outside formal meditation, mushin manifests in daily activity when one performs a task without overthinking or self-consciousness. In traditional Zen arts, such as the tea ceremony, archery, or brush painting, practitioners aim to act from this centerless clarity. Action arises from conditions, not from the ego’s desire to control or succeed. As such, mushin represents not inaction, but action freed from distortion.

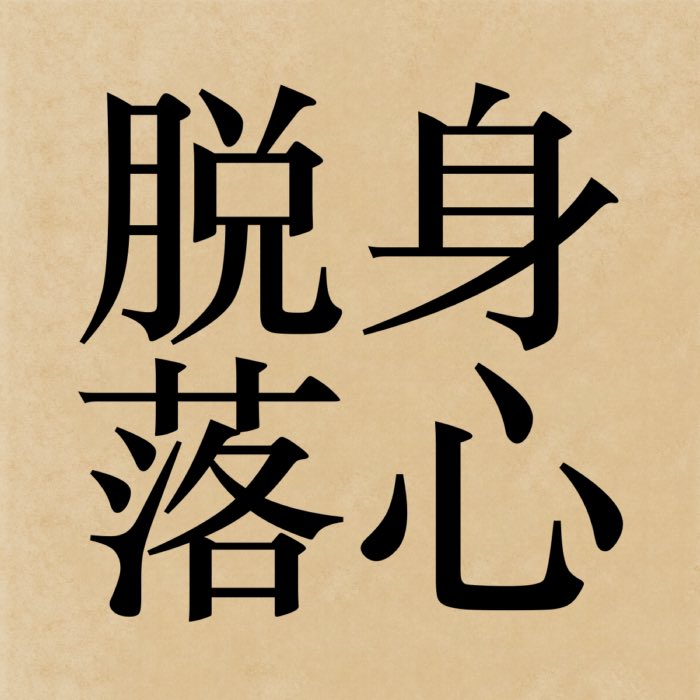

Zen literature often emphasizes that mushin cannot be attained through striving. The more one attempts to achieve a state of no-mind, the more the ego asserts itself. Like datsuraku, mushin is not a technique but a consequence — what remains when grasping falls away. It appears in the moment when the mind no longer hesitates, resists, or strategizes.

Buddhist background and comparison

Mushin aligns closely with the early Buddhist insight into non-self (anattā) and the cessation of the five hindrances:

- sensual desire (kāmacchanda),

- ill will (vyāpāda),

- sloth and torpor (thīna-middha),

- restlessness and remorse (uddhacca-kukkucca), and

- doubt (vicikicchā).

In particular, it parallels the mental clarity described in the jhāna states, where thought and evaluation drop away and a pure form of mindfulness remains. The difference lies in Zen’s presentation: while early Buddhism often describes meditative states analytically, Zen highlights their spontaneous, non-conceptual character.

In Mahāyāna terms, mushin reflects prajñā (wisdom) operating without duality. It recalls the idea of nirvikalpa-jñāna, or non-conceptual knowing. A mode of perception in which the division between subject and object dissolves. Zen’s particular strength lies in how it links this insight not only to meditative stillness but also to responsive activity in everyday life.

From a comparative perspective, mushin contrasts sharply with Western philosophical ideals that prize rational deliberation as the mark of freedom and maturity. Whereas much of Western thought equates agency with conscious control, mushin suggests that true freedom arises when action flows without self-reference. It is not irrationality but trans-rational clarity.

Conclusion

Mushin encapsulates an essential feature of Zen training: the cultivation of clarity and responsiveness not through effortful mental control, but through the natural falling away of grasping and self-centered reactivity. Rather than aiming for a blank or detached mind, mushin embodies a lucid engagement with experience, free from internal division. This state aligns closely with Siddhartha Gautama’s insight that liberation arises not from the domination of mind over conditions, but from ceasing to construct a self around experience. Critically, mushin also marks a divergence from traditions that associate maturity with intensified rational control; it reframes freedom as a quality of unobstructed presence rather than strategic mastery. In doing so, it affirms the Zen view that the highest form of action arises when mind, body, and circumstance flow together without friction or contrivance.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Mushin, Die Zen-Lehre vom Nicht-Bewusstsein, Das Wesen des Zen nach den Worten des Sechsten Patriarchen, 1. Januar 1996

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments