Datsuraku: Dropping off body and mind

Of the various phrases attributed to the Zen tradition, few are as central and enigmatic as shinjin datsuraku (身心脱落), often translated as “dropping off body and mind”. This expression is most famously associated with Dōgen, the founder of the Japanese Sōtō Zen school in Japan, and it reflects one of the most pivotal states of mind in Zen training. Unlike metaphorical or symbolic phrases, datsuraku describes a concrete experiential shift — one that resonates deeply with the core Buddhist insight into non-self (anattā), impermanence (anicca), and the cessation of attachment (taṇhā).

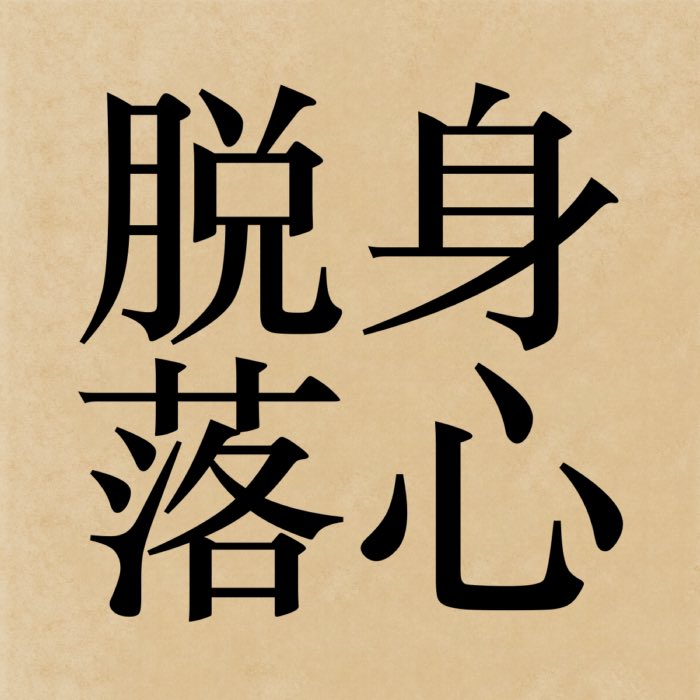

The kanji 身心脱落, which reads shinjin datsuraku in Japanese, literally means “dropping off body and mind”. The first character, shin (身), refers to the body or physical form. The second character, jin (心), means mind or heart. The third character, datsu (脱), indicates shedding or casting off. The final character, raku (落), means to fall or drop. Together, they convey the idea of a complete letting go of both bodily self-attachment and mental clinging.

Note

For an in-depth discussion of shinjin datsuraku (“dropping off body and mind”) as taught by Dōgen, including its historical context and broader philosophical significance, please refer to our dedicated post: Shinjin Datsuraku: The radical shedding of body and mind in Dōgen’s Zen. That article explores shinjin datsuraku in its full doctrinal and historical depth. Here, we will deal with a shorter, practical overview of datsuraku as a mental state cultivated within everyday Zen practice.

Origin and meaning

The phrase originates from a transformative moment in Dōgen’s life. During his time in China, while practicing under the teacher Tendō Nyojō, Dōgen reportedly attained a profound realization when Nyojō shouted at a fellow monk to “drop off body and mind”. According to tradition, Dōgen later remarked that at that moment, he himself experienced this shedding, marking a critical turning point in his practice.

Datsuraku consists of two characters: 脱 (datsu), meaning “to shed” or “to cast off”, and 落 (raku), meaning “to fall” or “to drop”. Together they indicate a spontaneous and complete letting go. When paired with 身心 (shinjin, body-mind), the phrase refers not merely to the physical body and mental contents but to the entire structure of identity and grasping that constitutes ordinary experience.

The phrase does not imply dissociation or nihilistic detachment. Rather, it refers to the falling away of dualistic identification. One does not become a disembodied mind or a passive observer, but instead experiences life without the habitual filters of ownership, resistance, or self-reference. This mirrors the early Buddhist teaching that suffering arises from clinging to the Five Aggregates (pañcakkhandha) as “I” or “mine”.

Datsuraku in practice

In practical terms, datsuraku is not something one can willfully bring about. It cannot be forced through discipline or attained through conceptual understanding. Zen teachers frequently warn that striving for it only reinforces the very structure one aims to shed. Nevertheless, it is not an accident either; it arises through sustained meditative practice, particularly zazen, where the body and mind are allowed to settle without interference.

When a practitioner experiences datsuraku, even momentarily, a shift occurs in which thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations continue to arise, but the compulsion to appropriate them into a fixed identity falls away. There may still be joy or discomfort, effort or ease, but the mental framework that normally says “this is happening to me” no longer dominates perception.

Dōgen emphasized that shinjin datsuraku is both the beginning and the continuation of true practice. It is not a single event or attainment but an ongoing undoing — an ever-deepening release of habitual identification. The phrase therefore functions less as a goal and more as a description of the quality that emerges when one stops interfering with experience.

Conceptual resonance and Buddhist background

Datsuraku is perhaps the most direct expression in Zen of the core Buddhist insight into non-self. Siddhartha Gautama taught that what we call a “self” is merely a conditioned process involving form, feeling, perception, mental formations, and consciousness. Insight into this leads not to despair but to freedom. The dropping away of attachment to these components is precisely what datsuraku expresses.

Unlike some schools that treat realization as a progressive journey through defined meditative stages, Zen often presents awakening as sudden and unstructured. In this context, datsuraku is not the product of climbing a ladder, but what occurs when the ladder itself is let go. This aligns with the Mahāyāna emphasis on śūnyatā (emptiness), the insight that all phenomena, including the self, are devoid of inherent substance.

Philosophically, datsuraku is consistent with Zen’s resistance to reifying spiritual ideals. It does not propose a purified or transcendent self but removes the framework that demands such a self in the first place. What remains is not a void, but an immediate, unburdened presence, a direct participation in the flux of reality without superimposed structure.

Conclusion

Datsuraku summarizes a core aspect of Zen practice: liberation is not achieved through accumulation or intellectual refinement, but through the spontaneous release of attachment to identity and constructs. It reflects the insight that direct experience is already unobstructed when the mechanisms of grasping and resistance are allowed to fall away. Rather than emphasizing stages or gradual development, Zen points to this immediate possibility through non-clinging engagement with reality. In this way, datsuraku critically highlights a distinction from traditions that focus on building a perfected self; instead, it represents a return to an unburdened presence, consistent with Siddhartha Gautama’s original insight into the cessation of suffering through the relinquishment of craving and fixed views.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments