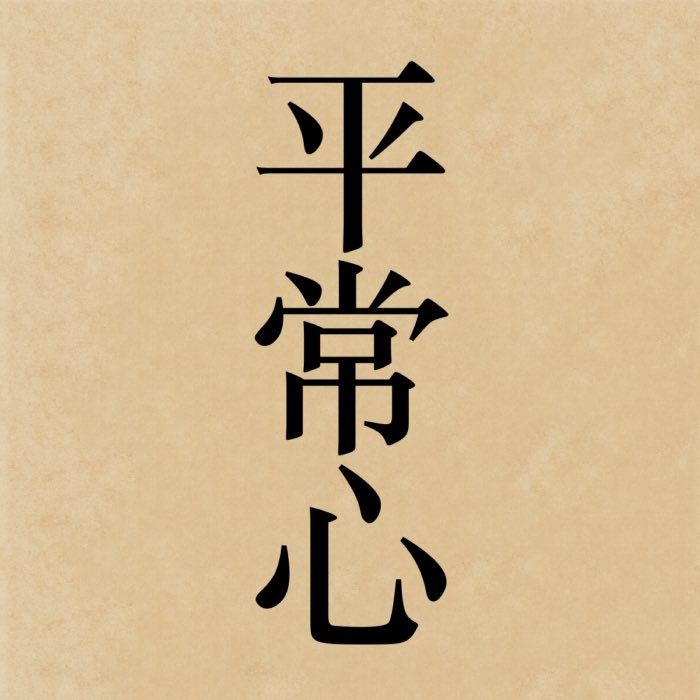

Heijōshin: The everyday mind

Heijōshin (平常心), translated as “everyday mind” or “ordinary mind”, is a pivotal yet often understated concept in Zen practice. It refers to a state of mental equanimity that is neither exalted nor diminished, neither special nor dull. Unlike terms such as samādhi or kenshō that imply depth or breakthrough, heijōshin points to a mode of being that is utterly natural, integrated, and non-dualistic. In Zen discourse, it is often said that “ordinary mind is the Way” (heijōshin kore dō), a phrase that highlights the tradition’s radical reorientation of spiritual ideals.

The kanji 平常心, which reads heijōshin in Japanese, literally means “everyday mind”. The first character, 平 (hei), means “calm” or “balanced”. The second character, 常 (jō), means “constant” or “usual”. The third character, 心 (shin), means “mind” or “heart-mind”. Together, they convey the idea of a state of mind that is calm and stable, precisely because it is not seeking anything beyond what is present.

Etymology and context

The term combines three characters: 平 (hei, “calm” or “balanced”), 常 (jō, “constant” or “usual”), and 心 (shin, “mind” or “heart-mind”). Together, they describe a state of mind that is calm and stable, precisely because it is not seeking anything beyond what is present. Heijōshin is not an elevated or altered state—it is the uncontrived mind that exists prior to dualistic differentiation, the state in which nothing is added and nothing is resisted.

The phrase is most famously associated with a Zen dialogue recorded in the Mumonkan (Gateless Gate), in which a monk asks Master Zhaozhou, “What is the Way?” Zhaozhou replies, “Ordinary mind is the Way.” When the monk asks whether one should direct oneself toward it, Zhaozhou responds, “If you try to direct yourself, you go away from it.” This exchange reflects Zen’s emphasis on immediacy, non-striving, and the dissolution of subject-object duality.

Heijōshin in Zen practice

In practical terms, heijōshin is cultivated by learning to meet each moment without embellishment. It involves a shift away from the search for extraordinary states and toward a deep appreciation of the ordinary. This is not to romanticize daily life but to recognize that profound insight is not separate from simple activity. Sitting, walking, washing a dish, or writing a sentence—all of these can express awakening when performed without attachment or resistance.

In zazen, heijōshin manifests as a quality of natural presence. The practitioner does not aim to eliminate thoughts, reach a heightened state, or manipulate attention. Rather, they allow the mind to settle into its own rhythm, neither grasping nor pushing away experience. This attitude supports a seamless integration between meditation and everyday activity, echoing the Mahāyāna teaching that saṃsāra and nirvana are not-two when rightly seen.

Crucially, heijōshin is not passivity or indifference. It allows for full engagement with life while remaining unentangled. Joy and sorrow, gain and loss—these pass through the mind without leaving residue. This reflects the early Buddhist teaching on equanimity (upekkhā) and the abandonment of clinging (upādāna), which lie at the heart of liberation.

Comparison and philosophical perspective

Philosophically, heijōshin challenges both spiritual exceptionalism and ordinary distraction. It denies that awakening requires rarefied states, while also refusing the dullness of habitual life. It invites a reconfiguration of values: clarity over excitement, presence over intensity, and responsiveness over conceptual knowing.

In contrast with many Western philosophical or religious frameworks that locate wisdom in elevated experience or moral purity, Zen’s emphasis on heijōshin places the locus of transformation in the everyday. The ordinary is not a place to escape from but the site where realization unfolds. The practitioner does not ascend to wisdom; they descend into presence.

Zen’s insistence on heijōshin as the Way is also a corrective to spiritual ambition. It deconstructs the ego’s tendency to project meaning onto dramatic events or mystical insights. Instead, it points to the simplicity of awareness that is neither self-reflective nor self-enhancing. In this way, heijōshin shares ground with the early Buddhist path, which prioritizes ethical and meditative clarity over metaphysical speculation.

Conclusion

Heijōshin captures a key insight of Zen: that realization is not an extraordinary achievement but the continuous unfolding of awareness in everyday life. It reframes the path as a shift in perception rather than a journey toward distant goals. Critically, heijōshin challenges models of spiritual attainment that emphasize dramatic experiences or elevated states, offering instead a vision where clarity and equanimity arise within the ordinary course of existence. In this sense, it affirms a central Buddhist principle: liberation is not apart from the conditions of daily life, but is realized through unobstructed, sincere engagement with each moment.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments