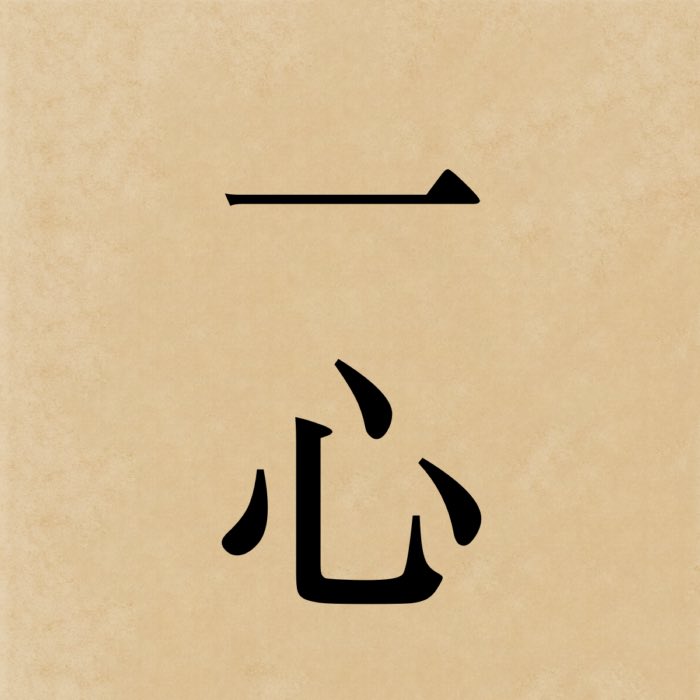

Isshin: The undivided mind

Isshin (一心), translated as “one mind” or “wholeheartedness”, expresses a quality of total engagement, sincerity, and undivided presence. In Zen practice, this state of mind is not merely about focus or intensity, but about bringing the full self — body, mind, and intention (shingitai) — into alignment with the activity at hand. While terms like mushin or fudōshin emphasize emptiness or equanimity, isshin emphasizes unity: a collectedness of purpose that dissolves inner division. It is often evoked in the context of practice, ritual, and everyday action where presence matters more than outcome.

The kanji 一心, which reads isshin in Japanese, literally means “one mind”. The first character, 一 (ichi), means “one” or “single”. The second character, 心 (shin), means “mind” or “heart-mind”. Together, they convey the idea of a unified state of mind that is undivided and fully present.

Etymology and usage

The term isshin combines 一 (ichi, “one”) and 心 (shin, “mind” or “heart-mind”), literally meaning “one mind” or “undivided mind”. It implies not simply concentration (samādhi in its technical sense) but an attitude of wholehearted sincerity. It can refer to the quality of doing something with full commitment, or the mental unity that arises when doubt, hesitation, and self-consciousness fall away.

In Japanese culture more broadly, isshin conveys a deep sense of devotion or sincerity, as in isshin ni naru (“to become of one mind”). In Zen, this devotion is not sentimental but practical: it means to act without internal contradiction, to meet the moment without fragmentation.

Isshin in Zen practice

In zazen, isshin is expressed not only in sustained attention but in the posture, breath, and demeanor of the sitter. One sits fully, not partially; the body is upright, the mind collected, the attention stable. When wandering thoughts arise, they are noticed and released — not with aversion, but with a return to unified presence.

In everyday practice, isshin can be seen in how tasks are approached. Whether preparing a meal, offering incense, or writing a letter, the act is done with undistracted care. Zen teachers often emphasize that how one does something is more important than what is done. The quality of attention infuses the action with integrity.

Importantly, isshin does not require dramatic intensity. It is not about force of will but about sincerity. Even small, routine actions can be expressions of isshin when performed with presence and intention. In this way, isshin supports the broader Zen principle that realization is not a matter of special states, but of how one engages ordinary life.

Philosophical perspective and Buddhist foundations

Isshin can be understood as a practical extension of right effort (sammā vāyāma) and right mindfulness (sammā sati) on the Eightfold Path. It signifies an attitude of diligence and attentiveness without strain. As with many Zen concepts, its value lies not in abstraction but in embodiment.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, isshin resonates with the integration of wisdom (prajñā) and method (upāya), where the practitioner’s understanding must be enacted through committed action. In that sense, isshin is also closely tied to the Bodhisattva ideal: to respond to the needs of the world not with partiality or indecision, but with unified purpose and clarity.

Philosophically, isshin offers an alternative to fragmented modern subjectivity, where attention is often divided, motivations conflicted, and presence diluted by distraction. Rather than seeking control, isshin invites integration. It proposes that the mind does not need to be empty of content, but empty of contradiction.

Conclusion

Isshin expresses a fundamental aspect of Zen practice: the integration of mind, body, and action into a coherent, undivided presence. It emphasizes that realization is not confined to seated meditation or moments of special insight but is embedded in the way ordinary activities are approached and performed. Critically, isshin challenges models of practice that prioritize inner states over outward behavior, highlighting instead that sincerity and attentiveness in action are themselves expressions of clarity. In doing so, it underscores a broader Buddhist insight: that freedom is realized not apart from daily life, but precisely through meeting it with a unified, undistracted mind.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments