Mosshōseki: What does it mean to leave no trace behind?

Zen teaching emphasizes not only the importance of mindfulness and compassion but also the manner in which actions are carried out and let go. Among its subtle principles is Mosshōseki — the idea of living and acting without leaving traces of attachment or self-reference. In this post, we explore the meaning of Mosshōseki, its Buddhist foundations, and its practical application in daily life, reflecting a central dimension of the Zen approach to freedom and responsibility.

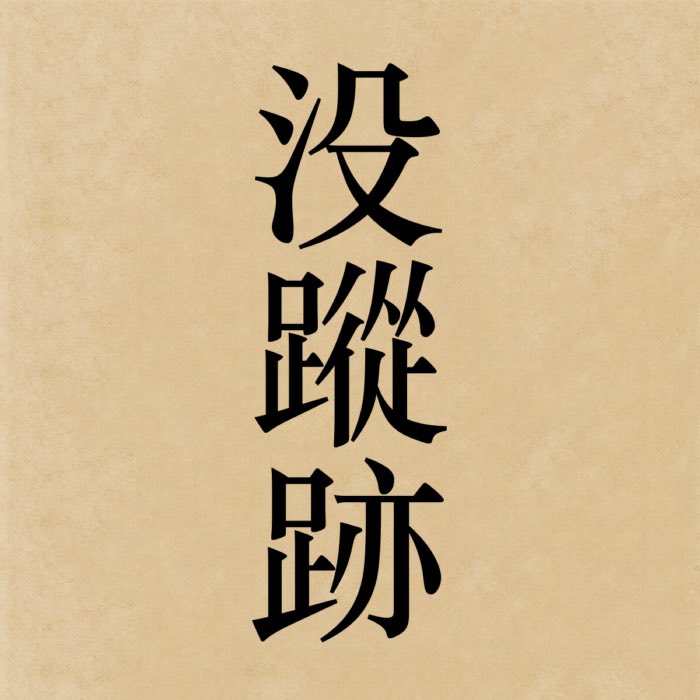

The kanji 没蹤跡, which reads mosshōseki in Japanese, literally means “leave no trace behind”. The first character, 没 (motsu), means “to leave” or “to pass away”. The second character, 蹤跡 (shōseki), means “trace” or “footprint”. Together, they convey the idea of acting in a way that does not leave behind any marks or residues of attachment. In Zen, this principle is often illustrated through the metaphor of a bird flying through the sky or a fish swimming in water, both of which leave no trace of their passage.

Meaning

Mosshōseki (没蹤跡) is a philosophical principle in Zen Buddhism, meaning “leave no trace behind”. It describes a way of living that matures through a balanced path between the drive to actively shape the world and the mindful preservation of what exists. A life clinging either to forceful assertion or to passive withdrawal falls out of harmony with the natural unfolding of reality. True maturity in Zen lies in embodying a Middle Way that responds to conditions without clinging to personal will or fearful avoidance.

The Eightfold Path trains us to overcome the illusion of a fixed self and to remove the defilements clouding our mind, enabling the direct experience of reality in its true nature, suchness (tathatā). Through this process, the illusions that obscure our original nature are removed, allowing its ever-present reality to be directly lived and expressed. When actions arise from this clarity, they are no longer expressions of a constructed personality but spontaneous manifestations of reality’s suchness through the embodied being.

In Zen, practice is embodied as a natural unity of mind and body. Our mental state expresses itself through our posture, speech, and actions, while the way we move and act in the world continuously influences the state of our mind. The discipline of zazen itself reflects this inseparability: an upright, stable posture supports clarity and equanimity, just as a settled mind supports graceful, attentive action. Zen often emphasizes that realization is not abstract but visible in the direct, integrated manner in which a person lives and acts.

Mosshōseki articulates the principle that in every moment of life, we face a choice: between active engagement and mindful restraint. A mature character is defined by the ability to walk the middle path between these two extremes. Relying solely on one or the other inevitably leads to harm — both to oneself and to others.

Buddhist foundations and philosophical background

The principle of Mosshōseki finds its roots in central Buddhist teachings. In early Buddhism, the notion of non-attachment (anupādā) is repeatedly emphasized: suffering arises not from phenomena themselves but from the clinging and craving that seize upon them. To act without leaving a trace is to engage with life without the grasping mind that appropriates experiences into a fixed sense of self.

Moreover, the insight into impermanence (anicca) underlines that all conditioned things arise and pass away. Zen extends this realization into the sphere of action: just as thoughts and sensations should not be clung to in meditation, so actions should not become sources of personal identity or pride. When there is no attachment to outcome, and no construction of self through action, deeds leave no residue.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, particularly in the Prajñāpāramitā tradition, the perfection of wisdom (prajñāpāramitā) teaches that true compassion and wisdom arise when actions are performed without clinging to notions of giver, gift, or recipient. This perspective informs the Zen view that actions, while compassionate and responsive, must not solidify into narratives of personal virtue or achievement.

Thus, Mosshōseki represents a lived expression of core Buddhist insights: acting fully and responsively in the world, while leaving no trace of self-reference behind.

Leaving no trace behind in practice

Just as a bird leaves no trail in the sky and a fish leaves no track in the water, so should a human being live. Like sunlight that touches the earth, sliding over grains of dust and sand without disturbing them, so too should human actions leave no trace, neither disrupting nor clinging to the flow of conditions. Every life, by its nature, strives to shape the world in accordance with its unique capabilities. It does not passively accept the given world but participates in its transformation. Yet life is also bound to the natural rhythms of arising and passing away, rhythms that must ultimately be accepted.

The more forcefully one shapes the world, the more one risks destroying; the more one refrains from shaping, the more one risks neglecting one’s human purpose. Only a balanced relationship between giving and receiving, freedom and responsibility, ambition and duty ensures the full maturation of a human life. Mosshōseki points to a way of living where one seeks this balance.

“Leaving no trace” means seeing reality as a unified, dynamic process and acting appropriately from a grounded clarity cultivated through zazen. Actions emerge naturally from a mind unobstructed by clinging, without aggressive interference or negligent withdrawal.

Unjustified demands and disrespectful attitudes toward life not only obscure the view of reality’s true nature but endanger life itself. An undisciplined mind, dominated by selfish desires, removes itself from the natural order and weaponizes its faculties, thereby harming other beings. Instead of realizing its potential, the self-centered person erects themselves as the center of a personal world, blind to the consequences of their actions.

Driven by personal cravings and fantasies, such a person takes what belongs to others or engages in behavior that endangers life. They “leave a trace” (goseki), disrupting the delicate fabric of existence.

Following the middle path between active shaping and mindful preservation, and embodying this in one’s way of life, leads naturally to compassion and contributes to the sustenance of life in all its forms.

Thus, the principle of Mosshōseki ultimately points to the insight that human beings are born for both action and mindful endurance. Their task is not blind assertion or passive resignation, but attentive engagement with life — an engagement aligned with the silent, intuitive expression of reality’s suchness.

Conclusion

The principle of Mosshōseki captures a subtle but fundamental aspect of Zen practice: to participate fully in the world without appropriating experiences into a constructed self. It teaches that true engagement does not mean grasping at outcomes or withdrawing in resignation, but acting responsively, based on the needs of each moment, and then letting go without residue.

Unlike traditions that emphasize building legacies or asserting lasting influence, Zen — through Mosshōseki — presents a model of conduct that resists fixation. Action is performed fully, but not clung to. This orientation differs sharply from many Western perspectives that celebrate permanence, ownership, and personal authorship.

Nevertheless, Mosshōseki is not a call to passivity. Rather, it advocates for a Middle Way: a path that balances commitment with non-attachment. By acting without seeking self-confirmation, the practitioner lives in harmony with impermanence and interdependence. Such a way of being reflects the broader Buddhist insight that freedom arises not from control or accumulation, but from the absence of clinging.

In this light, Mosshōseki does not describe an extraordinary ideal reserved for spiritual elites. It outlines a practical, everyday discipline: to act wholeheartedly, to release gracefully, and to leave no trace beyond what the unfolding moment naturally carries forward.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments