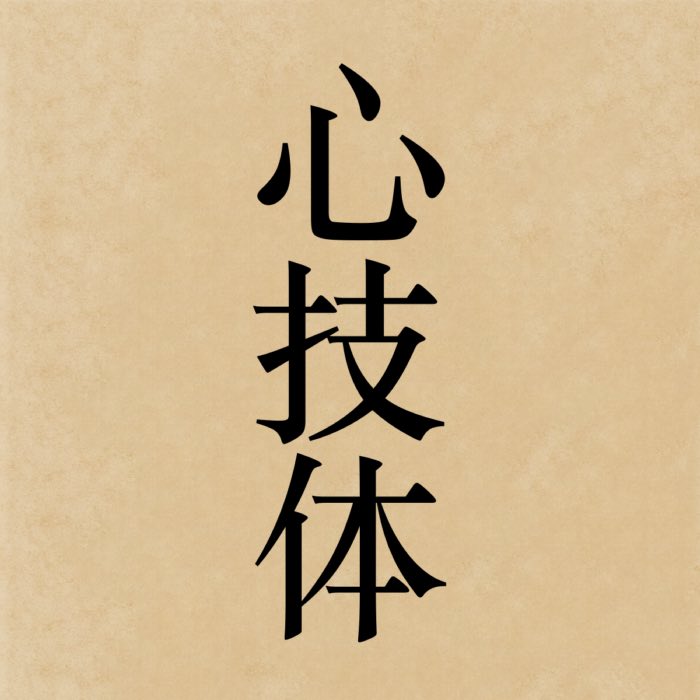

Shingitai: The unity of mind, technique, and body

Shingitai (心技体), meaning “mind, technique, and body”, describes a comprehensive integration of internal attitude, skillful action, and physical embodiment. Although the term is especially well known in Japanese martial arts, it has deep resonance within Zen, where practice is never purely mental or purely physical but demands a total engagement of being. In the Zen context, shingitai highlights that awakening is not a matter of intellectual insight alone, but of the seamless unity of thought, behavior, and presence. This deeper integration builds naturally on the foundational unity of mind and body described by shinshin, expanding it into the active domains of skillful engagement and methodical action.

The kanji 心技体, which reads shingitai in Japanese, literally means “mind, technique, and body”. The first character, 心 (shin), means “mind” or “heart-mind”. The second character, 技 (gi), means “skill” or “technique”. The third character, 体 (tai), means “body” or “physical form”. Together, they convey the idea of a unified state of being that integrates mental clarity, skillful action, and physical embodiment.

Etymology and traditional usage

The term shingitai is composed of three characters:

- 心 (shin): mind, heart-mind, or spirit

- 技 (gi): skill, technique, or method

- 体 (tai): body or physical form

Together, they express the idea that true mastery, or in Zen terms, true realization, requires the harmonious cultivation of all three dimensions. None is independent; mind without technique is ineffective, technique without spirit is hollow, and body without integration leads to imbalance.

Originally prominent in martial disciplines such as judo, kendo, and karate, shingitai provides a framework for understanding the total person as an interdependent system. Zen adapts this model to emphasize that clarity of mind, correctness of action, and rootedness in the body are all expressions of awakened presence.

Shingitai in Zen practice

In zazen, shingitai manifests as the seamless and dynamic integration of posture (body), attentiveness (mind), and method (technique). Proper posture is not only a physical arrangement but an expression of mental clarity and stability, supporting a state where mind and body are synchronized rather than operating in tension. Attentiveness arises not through forceful effort but through the natural settling of body and breath, allowing awareness to remain open and grounded. Technique in zazen, whether it concerns hand position, breathing, or gaze, is not mechanical but a living expression of unity between spirit, form, and method. Thus, to “sit” in Zen is not merely to assume a position, but to embody an undivided state where body, mind, and technique mutually sustain and refine one another in real time, reflecting the non-dual nature of practice and realization.

During ceremonial activities such as bowing, chanting, or offering incense, shingitai is enacted through the deliberate integration of intention (mind), method (technique), and physical form (body). These activities are not secondary to seated meditation; rather, they are essential sites where practice is revealed through embodied expression. Each movement is performed with full presence, attention to detail, and respect for form, ensuring that mind, technique, and body function together without contradiction or excess. When properly understood, even the smallest gesture in ceremony becomes an expression of unity, where thinking, doing, and being are no longer fragmented but manifest as a coherent, continuous flow of practice in action.

In everyday life, shingitai is expressed in how one engages with work, relationships, and responsibilities, transforming ordinary activities into fields of continuous practice. A mindful presence (shin) provides the emotional and cognitive foundation for responsiveness; skillful execution (gi) ensures that actions are appropriate, effective, and attentive to context; and embodied rootedness (tai) anchors these qualities in physical form and behavior. Through this integration, actions emerge not as habitual reactions but as deliberate, measured expressions of awareness. In this way, practice is not confined to the meditation hall but becomes the very fabric of daily existence, dissolving the artificial boundary between spiritual practice and worldly engagement. Realization thus manifests not as an isolated achievement but as a continuous, dynamic responsiveness to the conditions of life.

Buddhist foundations and philosophical relevance

The principle behind shingitai aligns closely with the Buddhist understanding of dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda) and the non-duality of form and emptiness (rūpa śūnyatā). In early Buddhist teachings, ethical conduct (sīla), meditation (samādhi), and wisdom (paññā) are mutually supportive; no single element alone leads to liberation. Shingitai echoes this interdependence, reminding practitioners that realization is embodied, enacted, and lived — not merely conceptualized.

Philosophically, shingitai challenges compartmentalized views of the self that are prevalent in modern life, where intellectual work, physical activity, and emotional development are often treated as distinct and unrelated pursuits. Zen’s emphasis on shingitai resists this fragmentation, insisting that true insight must permeate every aspect of being: mental clarity must express itself physically, physical discipline must reflect mindful intent, and skill must be infused with spirit. Without this integration, realization remains partial, abstract, and unstable.

Compared to many Western traditions that privilege mind over body or prioritize theory over practice, Zen — through shingitai — proposes a holistic vision where wisdom is not confined to thought but must manifest concretely in action. Skill is not merely technical competence but an embodiment of insight; presence is not a mental abstraction but a quality evident in posture, gesture, and engagement. In this way, shingitai underscores that awakening in Zen is a dynamic, embodied realization — one that transforms not only how a practitioner thinks but how they move, act, and live.

Conclusion

Shingitai highlights a critical dimension of Zen practice: that awakening is not an abstract insight but a fully embodied integration of mind, skill, and body. It emphasizes that realization must permeate conduct and presence, not remain confined to conceptual understanding. Shingitai challenges notions of practice that separate thinking from doing or contemplation from action, reinforcing a view where true insight is enacted in the world through aligned, responsive activity. In this way, it offers a corrective to both overly intellectualized and narrowly physical models of practice, presenting a holistic vision where wisdom, method, and embodiment continually reinforce each other.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments