Piprahwa: The Buddha’s relics and the history of their archaeological discovery

For more than a century, the Piprahwa stūpa has captivated archaeologists, epigraphers, and historians of Buddhism. As the site of a controversial yet remarkably early inscription that may refer to the historical Buddha, it holds both archaeological promise and interpretive tension. Discovered in the colonial era and revisited by modern researchers, Piprahwa offers a rare case where textual tradition, ritual architecture, and material remains converge. In this post, we briefly examine the discovery, debates, and evolving significance of Piprahwa in the ongoing effort to understand the historical foundations of Buddhism.

Piprahwa vase with relics of the Buddha. The inscription reads: …salilanidhane Budhasa Bhagavate… (Brahmi script: …𑀲𑀮𑀺𑀮𑀦𑀺𑀥𑀸𑀦𑁂 𑀩𑀼𑀥𑀲 𑀪𑀕𑀯𑀢𑁂…) “Relics of the Buddha Lord”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Introduction

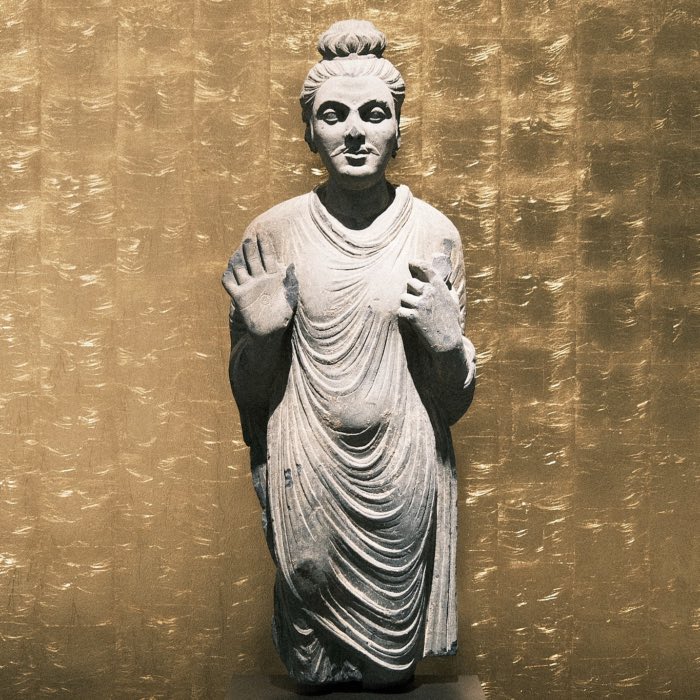

The Piprahwa stupa occupies a unique and contested place in the field of Buddhist archaeology. Situated near the India-Nepal border and long associated with the ancient Śākya clan to which Siddhartha Gautama belonged, the site has drawn scholarly and popular interest for over a century. Its significance lies primarily in the discovery of a reliquary casket bearing a Brahmi inscription that some scholars interpret as referring to the Buddha’s relics, potentially making Piprahwa one of the earliest and most direct archaeological links to the historical Buddha.

Stupa at Piprahwa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Discovered in 1898 by British landowner William Claxton Peppé, the site initially generated excitement across colonial and scholarly circles. The discovery included a brick stūpa, a stone coffer, and bone fragments, all of which pointed toward an ancient and carefully executed ritual burial. The inscription, however, quickly became the center of intense scholarly debate, with disagreements emerging over its translation, authenticity, and historical implications.

Today, Piprahwa continues to be a focal point for discussions about the early spread of Buddhism, relic worship, and the material culture of the Mauryan period. While some view the find as compelling evidence for the historicity of relic distribution after the Buddha’s death, others caution against drawing firm conclusions without more definitive corroboration. In this post, we examine the archaeological context, epigraphic debates, and broader implications of the Piprahwa discovery within the framework of Buddhist historiography.

Historical and geographical context

Piprahwa is located in the Siddharthnagar district of Uttar Pradesh, India, near the modern border with Nepal. Geographically, it lies only a few kilometers south of the site of Tilaurakot, which is widely proposed as the historical location of Kapilavastu, the capital of the Śākya clan. This proximity is crucial, as it situates Piprahwa within the ancient Śākya domain and supports the theory that the stūpa may have originally been constructed by the Śākyas themselves, possibly in connection with the relics of Siddhartha Gautama.

The Śākya territory, at the time of the Buddha, was a politically semi-autonomous republic governed by a council of elders. The region was culturally linked to the broader Indo-Gangetic plains but maintained its own traditions, kinship structures, and religious practices. Siddhartha Gautama is said to have been born into this aristocratic lineage, and the cultural environment of the Śākyas, including their funerary and commemorative traditions, offers context for understanding the material remains at Piprahwa.

The significance of Piprahwa also emerges through its archaeological and cultural relationship with Tilaurakot, where urban fortifications, monastic compounds, and early brick structures have been uncovered. The two sites may have functioned as complementary nodes within a broader regional network of early Buddhist practice. Theories linking Piprahwa to the distribution of the Buddha’s relics after his cremation further enhance its historical profile and justify its inclusion in serious discussions on the archaeology of early Buddhism.

This close alignment between geography, tradition, and political history provides a compelling framework within which to evaluate the site’s importance. Piprahwa’s location within the Śākya heartland adds weight to interpretations that see it not merely as a later devotional site, but potentially as one of the earliest centers of relic worship tied directly to the life and legacy of the historical Buddha.

Discovery of the Piprahwa stupa

The discovery of the Piprahwa stūpa in 1898 was a landmark moment in the history of South Asian archaeology. William Claxton Peppé, a British colonial landowner, undertook an excavation on his estate near the village of Piprahwa. Acting on reports of a mound containing bricks and pottery, Peppé oversaw the systematic excavation of what would prove to be a multi-tiered brick stūpa containing sealed relic chambers.

At the base of the stūpa, beneath layers of brickwork and earth, the excavation team uncovered a large stone coffer. Crafted with considerable skill, the coffer was carved from a single block of stone and contained several smaller reliquaries made of crystal, soapstone, and steatite. Among these were fragments of charred bone and ashes, wrapped in gold foil and stored alongside precious objects such as beads, gold flowers, and semi-precious stones.

The structure of the stūpa itself was substantial. Measuring around 6 meters in height and more than 20 meters in diameter, the monument featured concentric brickwork with a carefully laid foundation, suggesting professional construction rather than ad hoc burial. The core relic chamber was centrally positioned, accessible only through deliberate excavation, which underscores the sacred and secure nature of the deposit.

The combination of relic materials and luxury votive objects indicates a ritual context consistent with early Buddhist funerary and commemorative practices. Peppé’s detailed records and illustrations, unusually precise for his time, provided subsequent scholars with a reliable foundation for analysis. While his excavation methods lacked modern stratigraphic controls, the clear association between the relic chamber, inscription, and stūpa architecture made this find exceptional.

Thus, the Piprahwa discovery offers an early and materially rich example of Buddhist relic worship. The nature of the burial, the quality of the reliquaries, and the intentionality of the stūpa’s construction suggest it may have been established during a formative phase of Buddhist religious expression — possibly even connected to the historical distribution of the Buddha’s remains after his cremation.

Inscription on the reliquary

One of the most consequential elements of the Piprahwa discovery was a Brahmi inscription engraved on the lid of a soapstone casket found inside the main relic chamber. The inscription consists of six lines, written in early Brahmi script, and is widely believed to date to the 3rd century BCE. Although the precise translation has been the subject of scholarly disagreement, most early interpretations identify it as a dedicatory statement made by members of the Śākya clan, the Buddha’s own family.

A widely accepted rendering of the inscription reads:

“This relic container of the Buddha, the Lord (Bhagavato), is a donation of the Śākya brethren, their sisters and children.”

If this reading is correct, the inscription would represent a direct reference to the historical Buddha (Bhagavato Budhassa) and would affirm the claim that the reliquary contained a portion of his cremated remains. It would also support the canonical narrative that the Buddha’s relics were divided and enshrined by various groups, including the Śākyas. The inscription’s language and paleography correspond well with other known examples from the Mauryan period, lending credence to its antiquity.

Handwritten note by discoverer W. C. Péppe to Vincent Arthur Smith about the inscription, 1898. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

However, the interpretation has not gone unchallenged. Some epigraphers argue that alternative translations are possible, depending on how certain damaged characters are reconstructed and read. Doubts have also been raised about whether the term “Buddha” in this context refers to the Buddha or a more general title meaning “awakened one.” Critics further point to the possibility that the inscription could refer to a symbolic or later reliquary, made in memory rather than in possession of physical remains.

The authenticity of the inscription has also been questioned in light of the colonial context of its discovery. Peppé was a local British official with no formal archaeological training, and some later scholars expressed concern that the find might have been manipulated, if not forged, either to generate fame or to align with expectations of British antiquarian societies. However, no conclusive evidence of forgery has ever emerged, and Peppé’s records and the physical properties of the casket have generally withstood scrutiny.

The five reliquaries discovered in Piprahwa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In sum, the inscription remains a focal point in the debate over the historicity of Piprahwa’s claim to house the Buddha’s relics. If accepted as authentic and correctly interpreted, it constitutes one of the oldest surviving textual references to Siddhartha Gautama and his relic cult. Even under cautious readings, it offers invaluable insight into early Buddhist devotional language, epigraphy, and the role of the Śākya clan in memorializing the Buddha’s legacy.

Archaeological assessment

A close archaeological analysis of the Piprahwa stūpa reveals insights into both its chronological construction and its ritual function within early Buddhist practice. Although the 1898 excavation led by William Claxton Peppé was conducted prior to the development of modern stratigraphic methodology, subsequent studies and comparisons with other early Buddhist stūpas allow scholars to reconstruct the structure’s evolution and context with some confidence.

The stratigraphy observed during the excavation indicated multiple construction phases. The core relic chamber was positioned deep within the central axis of the mound and was surrounded by concentric brick layers and successive enlargements. These phases suggest that the original structure may have been a modest funerary mound that was later monumentalized — possibly during the Mauryan period and again in subsequent centuries. Though Peppé did not document each stratum with the precision expected today, his notes indicate a clear differentiation between the core chamber and the surrounding superstructure, implying a primary deposit that predates later architectural additions.

When compared to other early Buddhist stūpas, such as those at Sanchi, Bharhut, and Amaravati, Piprahwa stands out for its simplicity and apparent chronological antiquity. The absence of elaborate stone railings or narrative reliefs at Piprahwa, features typical of 2nd to 1st century BCE stūpas, suggests an earlier origin, likely closer in time to the initial dissemination of relics after the Buddha’s paranirvāṇa. The modest typology also resembles descriptions of the original stūpas built immediately following the Buddha’s cremation, as noted in textual sources like the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta.

The layout and design of the Piprahwa stūpa support this interpretation. The centrality of the relic chamber, the symmetry of the construction, and the inclusion of votive deposits are all consistent with early Buddhist mortuary architecture. The design reflects an intention to preserve and honor relics, reinforcing the idea that the structure functioned as a sacred reliquary from the outset. The quality of the stone coffer and the intentional sealing of the chamber further underscore the site’s ritual significance.

In sum, although the absence of full-scale modern excavation limits our stratigraphic precision, the available archaeological data strongly suggest that the Piprahwa stūpa was built and used during a period of early relic cult activity. Its form, context, and comparisons with other early stūpas all point to a significant role in the early architectural expression of Buddhist veneration and community memory.

Debates and controversies

The discovery of the Piprahwa inscription immediately sparked debate, and over a century later, it remains one of the most contested issues in Buddhist archaeology. Central to the controversy is the authenticity of the inscription and whether it genuinely refers to the historical Buddha’s relics or reflects a later, symbolic dedication.

One line of criticism focuses on the epigraphic interpretation. While the prevailing translation identifies the inscription as a dedication by the Śākya brethren of relics belonging to the Buddha (Bhagavato Budhassa), some scholars argue that the script is ambiguous and that alternative readings are grammatically or semantically plausible. Questions have also been raised about the term “Buddha” itself — whether it unambiguously refers to Siddhartha Gautama or could signify an awakened being in general, not necessarily the historical Buddha.

A more serious concern, raised especially during the early to mid-20th century, is the possibility of forgery or manipulation. Given the colonial context of the find — discovered by a British indigo planter with limited archaeological training — some critics suggested that the inscription might have been altered or fabricated to please colonial officials or fit contemporary expectations about Buddhist relics. This suspicion was compounded by the enthusiasm with which Peppé’s discovery was celebrated by British antiquarians and presented to institutions such as the Royal Asiatic Society.

However, most modern scholars and epigraphers have found no compelling evidence of fraud. The inscription’s stylistic features are consistent with 3rd century BCE Brahmi inscriptions, and the linguistic formulation closely aligns with other confirmed Mauryan-era relic dedications. Furthermore, recent technical analysis of the casket and its engraving has found no signs of modern tampering, supporting the view that the inscription is contemporaneous with the coffer and its contents.

The debate is further complicated by the ideological context of colonial archaeology. In the late 19th century, British administrators and scholars were deeply invested in linking India’s spiritual past to archaeological remains. This impulse, while productive in terms of documentation and conservation, sometimes encouraged interpretations driven more by religious sympathy or imperial romanticism than scientific neutrality. The Piprahwa case sits at this intersection of piety, politics, and early professional archaeology.

In conclusion, while skepticism about the Piprahwa inscription has served as an important check on premature historical conclusions, there is currently no conclusive reason to dismiss its authenticity. The inscription continues to serve as both a valuable data point and a reminder of the interpretive challenges that come with cross-cultural, colonial-era discoveries.

Later excavations and research

The initial excavation by William Claxton Peppé in 1898 brought Piprahwa to international attention, but the site’s full archaeological potential began to be realized only through later excavations conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and collaborative international teams. These efforts, carried out in multiple phases throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries, have significantly expanded our understanding of the site’s extent, chronology, and religious function.

Renewed excavations led by the ASI in the 1970s and early 2000s revealed that Piprahwa was part of a larger monastic and stūpa complex, not merely a single commemorative mound. Structures uncovered included monastic cells, boundary walls, subsidiary stupas, and paved walkways — features consistent with an organized Buddhist monastic settlement. These findings suggest that the site remained an active religious center well into the Kushan and Gupta periods, long after the original stūpa was constructed.

Southern monastery. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Archaeologists also uncovered additional reliquary chambers and votive offerings, some of which may date to post-Mauryan renovations of the site. This supports the idea that Piprahwa underwent successive waves of religious patronage, with later Buddhist communities reaffirming the sanctity of the site through architectural embellishment and secondary relic deposits.

Modern analytical techniques have further contributed to refining the site’s chronology. Radiocarbon dating of organic material found in association with the stūpa layers has supported a construction timeline beginning as early as the 3rd century BCE. Additionally, material analysis of the reliquaries and decorative elements, conducted through spectrometry and petrography, has confirmed the regional provenance and high craftsmanship of the artifacts, reinforcing their authenticity.

Collaborative work between Indian and foreign archaeologists has emphasized the importance of placing Piprahwa within a broader transregional context of Buddhist relic cults. Comparisons with similar stūpas in Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Central Asia reveal stylistic and ritual continuities that frame Piprahwa as part of a widespread and evolving tradition of sacred enshrinement.

In summary, later excavations and scientific analyses have validated and expanded upon Peppé’s original discovery. They have not only strengthened the argument for Piprahwa’s early Buddhist origins but also provided crucial data on the site’s long-term religious use, architectural evolution, and significance in the broader Buddhist world.

Significance for the historicity of the Buddha

The Piprahwa site holds significant implications for evaluating the historicity of Siddhartha Gautama and the early development of the Buddhist tradition. If the reliquary and its inscription are accepted as authentic, then Piprahwa offers one of the earliest physical attestations not only to the veneration of the Buddha but to his historical existence as a revered teacher whose remains were actively distributed and enshrined by members of his own kin group, the Śākyas.

Such a conclusion would lend material support to the canonical account found in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, which describes the cremation of the Buddha and the division of his relics among eight claimant groups. The notion that the Śākyas retained a portion of the relics aligns with both textual tradition and the apparent dedicatory inscription found at Piprahwa. While the archaeological context alone cannot confirm the identity of the cremated individual, the convergence of inscriptional language, mortuary architecture, and regional geography makes the hypothesis historically plausible.

Even if treated cautiously, Piprahwa provides a rare window into early Buddhist relic worship, revealing how the practice of enshrining physical remains emerged as a central devotional and institutional mechanism in the nascent Buddhist community. The design of the stūpa, the care in burial, and the votive offerings all point to a ritual culture deeply concerned with the commemoration of the Buddha’s bodily legacy. This materially grounded form of veneration helped transform abstract teachings into spatial and architectural realities that could unify and sustain the sangha across time and space.

Beyond its direct evidentiary value, Piprahwa has played a substantial role in shaping Buddhist historical narratives. For Indian and international audiences alike, the site has served as a focal point for imagining Buddhism’s earliest phase in tangible, archaeological terms. Whether regarded as the resting place of the Buddha’s relics or as a symbolic monument in honor of him, Piprahwa exemplifies how religious memory becomes embedded in the landscape — and how archaeology can both challenge and enrich traditional historiography.

Ultimately, the Piprahwa discovery contributes to a broader reassessment of the relationship between material evidence and religious tradition. While no single site can decisively settle questions of historicity, Piprahwa stands as one of the strongest candidates for linking the life of Siddhartha Gautama with the enduring physical record of early Buddhist faith and practice.

Conclusion

The Piprahwa stūpa remains one of the most significant and controversial archaeological sites associated with early Buddhism. Its discovery brought to light a reliquary and inscription that, if accepted as genuine, may provide some of the earliest material evidence for the historical Buddha and the distribution of his cremated remains. The architectural structure of the stūpa, the quality and nature of the relic deposits, and the paleographic features of the Brahmi inscription collectively form a compelling, though not conclusive, case for linking the site to early Śākya ritual and Buddhist relic cult practices.

In the decades following Peppé’s initial excavation, continued archaeological work has confirmed the complexity and longevity of the site. Piprahwa developed into a broader monastic complex that remained active through successive phases of Buddhist institutional growth. Scientific advances such as radiocarbon dating and material analysis have helped clarify the chronology and authenticity of its artifacts, while comparative studies have placed the site within a larger network of South Asian and transregional Buddhist centers.

Piprahwa’s relevance today extends beyond its local context. It exemplifies both the promise and the challenges of using archaeology to probe the roots of religious history. The debates surrounding the site’s interpretation — its inscription, its stratigraphy, and the motives of its discoverers — demonstrate the necessity of balancing textual tradition with scientific rigor. Future research will need to build upon existing excavations while applying modern techniques to test the many remaining hypotheses about Piprahwa’s role in early Buddhism.

Whether ultimately seen as the final resting place of the Buddha’s relics or as a revered commemorative site, Piprahwa continues to shape scholarly understanding of how memory, material culture, and sacred geography intersect in the formation of Buddhist heritage.

References and further reading

- Allen, Charles, The Buddha and Dr Führer: an archaeological scandal, 2008, 1st ed., London: Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-905791-93-4

- Allen, Charles, What happened at Piprahwa: A chronology of events relating to the excavation in January 1898 of the Piprahwa Stupa in Basti District, North-Western Provinces and Oude (Uttar Pradesh), India, and the associated ‘Piprahwa Inscription’, based on newly available correspondence, 2012, Zeitschrift für Indologie und Südasienstudien, 29: 1–19, OCLC 64218646

- Allen, Charles, The Buddha and the Sahibs: The Men Who Discovered India’s Lost Religion, 2003, John Murray, ISBN: 978-0719554285

- Strong, John S., Relics of the Buddha, 2024, Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House, ISBN: 978-9359035284

- Dani, AH, Indian Palaeography, 1997, 3rd ed. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, ISBN 978-8121500289

- Fleet, J. F., The Inscription on the Piprahwa Vase, 1907, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 39: 105–130. doi: 10.1017/S0035869X00035541ꜛ, Zenodoꜛ

- Coningham, Robin & Ruth Young, The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE, 2023, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521609722

- The Priprahwa Projectꜛ

comments